Pravni Zapisi 2020-02.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The

Religious Policy and Dissent in Socialist Hungary, 1974-1989. The Case of the Bokor-movement By András Jobbágy Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Nadia Al-Bagdadi Second Reader: Professor István Rév CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Statement of Copyright Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library, Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection 1 Notes on translation All of my primary sources and much of the secondary literature I use are in Hungarian. All translations were done by me; I only give a few expressions of the original language in the main text. CEU eTD Collection 2 Abstract The thesis investigates religious policy, church-state relationships and dissent in late Kádárist Hungary. Firstly, by pointing out the interconnectedness between the ideology of the Catholic grass-root Bokor-movement and the established religious political context of the 1970s and 1980s, the thesis argues that the Bokor can be considered as a religiously expressed form of political dissent. Secondly, the thesis analyzes the perspective of the party-state regarding the Bokor- movement, and argues that the applied mechanisms of repression served the political cause of keeping the unity of the Catholic Church intact under the authority of the Hungarian episcopacy. -

Rockin' the Church: Vernacular Catholic Musical Practices

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 4 Issue 1 Hungarian Catholicism: Living Faith Article 4 across Diverse Social and Intellectual Contexts March 2020 Rockin' the Church: Vernacular Catholic Musical Practices Kinga Povedak Hungarian Academy of Sciences, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the Aesthetics Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Cultural History Commons, Eastern European Studies Commons, European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Povedak, Kinga (2020) "Rockin' the Church: Vernacular Catholic Musical Practices," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 4: Iss. 1, Article 4. p.42-63. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1066 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol4/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Catholicism by an authorized -

The Martyrdom of Patience

The Martyrdom of Patience: The Holy See and the Communist Countries (1963-89), Agostino Casaroli, Rocco Giancarlo Racco, Fortunata Scopelliti, 2007, 0978280024, 9780978280024, Ave Maria Centre of Peace, 2007 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1USKo05 http://goo.gl/R5pFs http://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/?store=book&keyword=The+Martyrdom+of+Patience%3A+The+Holy+See+and+the+Communist+Countries+%281963-89%29 DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/RcIj6 http://bit.ly/1t9num1 Pietro a Mosca Cremlino, Santa Sede e perestrojka tra stati sovrani, Alceste Santini, Agostino Casaroli, 1991, Political Science, 248 pages. Vita e pensiero, Volume 27 , , 1941, Italy, . John Paul II a pictorial biography, Peter Hebblethwaite, Ludwig Kaufmann, Jul 1, 1979, Biography & Autobiography, 128 pages. Religion and Politics in Comparative Perspective Revival of Religious Fundamentalism in East and West, Bronislaw Misztal, Anson D. Shupe, Jan 1, 1992, Political Science, 223 pages. This volume proposes that across many cultures, the revival of religious fundamentalism is a response to the globalization of economies and markets, the weakening of the. Il filo sottile l'Ostpolitik vaticana di Agostino Casaroli, Alberto Melloni, 2006, Political Science, 435 pages. The Ambivalence of the Sacred Religion, Violence, and Reconciliation, R. Scott Appleby, 2000, Political Science, 429 pages. Terrorists and peacemakers frequently grow up in the same community and adhere to the same religious tradition. The killing carried out by one and the reconciliation fostered. The spiritual life a treatise on ascetical and mystical theology, Adolphe Tanquerey, 1930, Asceticism, 771 pages. 2. rev. udgave. originalГҐr: 1923.. L'Espresso, Volume 37, Issues 1-8 , , 1991, Italy, . Politica, cultura, economia.. Archivio italiano per la storia della pietГ , Volume 18 , Giuseppe De Luca, 2005, Religious literature, . -

The Priestly Patriotic Associations in the Eastern European Countries

231 Pregledni znanstveni članek (1.02) BV 68 (2008) 2, 231-256 UDK 272-784-726.3(4-11)«194/199« Bogdan Kolar SDB The Priestly Patriotic Associations in the Eastern European Countries Abstract: The priestly patriotic associations used to be a part of the every day life of the Catholic Church in the Eastern European countries where after World War II Com- munist Parties seized power putting in their programmes the elimination of the Catho- lic Church from the public life and in the final analysis the destruction of the religion in general. In spite of the fact that the associations were considered professional guilds of progressive priests with a particular national mission they were planned by their founders or instigators (mainly coming from various secret services and the offices for religious affairs) as a means of internal dissension among priests, among priests and bishops, among local Churches and the Holy See, and in the final stage also among the leaders of church communities and their members. A special attention of the totalitarian authorities was dedicated to the priests because they were in touch with the population and the most vulnerable part of the Church structures. To perform their duties became impossible if their relations with the local authorities as well as with the repressive in- stitutions were not regulated or if the latter set obstacles in fulfilling their priestly work. Taking into account the necessary historic and social context, the overview of the state of the matters in Yugoslavia (Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia), Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia demonstrates that the instigators of the priestly patriotic so- cieties followed the same pattern, used the same methods and defined the same goals of their activities. -

Pope's Visit to Synagogue 'Clear Message' of Good Will, Rabbi Says

Pope’s visit to synagogue ‘clear message’ of good will, rabbi says NEW YORK – Pope Benedict XVI’s April 18 visit to a synagogue during the New York leg of his U.S. visit is a “clear message of good will to the Jewish community,” said the rabbi hosting the pope. Rabbi Arthur Schneier, senior rabbi of Park East Synagogue, said his own commitment to interreligious dialogue prompted him to invite the pope to visit his house of worship. He extended the invitation while visiting the Vatican in March. “I have worked for 46 years for religious freedom, human rights and interreligious dialogue from my pulpit,” he said in an interview with Catholic News Service in the days leading up to the papal visit. “Our synagogue has been the scene of interreligious dialogue on many occasions,” he said. It has hosted Russian Orthodox Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow, Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople and the chief rabbi of Israel. Rabbi Schneier also is founder and president of the Appeal of Conscience Foundation, which he said “concerns itself with the situations involving oppressed Catholics, Jews and people of other religions.” On his way to an ecumenical prayer service at St. Joseph’s Church in the Yorkville section of Manhattan, Pope Benedict was to make a 20-minute visit to the Park East Synagogue. The synagogue is near where the pope is residing at the residence of the Vatican’s U.N. nuncio. On his last day in Washington, after meeting with 200 interreligious leaders, the pope met briefly with Jewish leaders. -

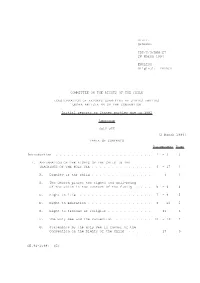

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION Initial reports of States parties due in 1992 Addendum HOLY SEE [2 March 1994] TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction ........................ 1 -3 3 I. AFFIRMATION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD IN THE TEACHINGS OF THE HOLY SEE............... 4 -17 3 A. Dignity of the child............... 4 3 B. The Church places the rights and well-being of the child in the context of the family .... 5 -6 4 C. Right to life .................. 7 -8 5 D. Right to education................ 9 -10 5 E. Right to freedom of religion........... 11 6 F. The Holy See and the Convention ......... 12-16 7 G. Statements by the Holy See in favour of the Convention on the Rights of the Child ...... 17 9 GE.94-15987 (E) CRC/C/3/Add.27 page 2 CONTENTS (continued) Paragraphs Page II. ACTIVITY OF THE HOLY SEE ON BEHALF OF CHILDREN .... 18-43 10 A. Holy See and Church structures dealing with children..................... 19-23 10 B. Implementation of the Convention......... 24-43 12 III. ACTIVITIES OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR THE FAMILY FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD....... 44-59 15 A. Meeting on the rights of the child (Rome, 18-20 June 1992) ............. 45-46 15 B. International meeting on the sexual exploitation of children through prostitution and pornography (Bangkok, 9-11 September 1992).......... 47-50 16 C. -

Foreign Policy Doctrine of the Holy See in the Cold War Europe: Ostpolitik of the Holy See

The Turkish Yearbook of International Relations, Volume 49 (2018), p. 117-141. DOI : 10.1501/Intrel_0000000319 Foreign Policy Doctrine of the Holy See in the Cold War Europe: Ostpolitik of the Holy See Boris Vukicevic Abstract This article deals with the foreign policy of the Holy See during the pontificates of Pope John XXIII and Paul VI which is known as the Ostpolitik of the Holy See. The Ostpolitik signifies the policy of opening the dialog with the communist governments of the Eastern and Central Europe during the Cold War. The article analyzes the factors that influenced it, its main actors and developments, as well as relations of the Holy See with particular countries. It argues that, despite its shortcomings, the Ostpolitik did rise the Holy See’s profile on the international scene and helped preservation of the Catholic Church in the communist Eastern and Central Europe. Keywords The Holy See, Ostpolitik, the Cold War, foreign policy, Eastern Europe Associate Prof. Dr., University of Montenegro, Faculty of Political Science. [email protected] (orcid.org/0000-0002-7946-462X) Makale geliş tarihi : 15.12.2017 Makale kabul tarihi : 06.11.2018 118 The Turkish Yearbook of International Relations, Volume 49 (2018) Introduction The Cold War, unlike any other period in history of international relations, made all the subjects of international relations from all over the world involved into world affairs. One of the more specific actors of this period, dealing more in the background, but still remaining influential, and, arguably, in certain periods, instrumental, was the Holy See. The Holy See, the governing body of the Roman Catholic Church, as a subject of international law and international relations -thus specific among religious organizations- had its own evolution during the Cold War years, as the whole system evolved from confrontation and crises toward détente and coexistence, and then again toward final cooling of relations before the end of this era. -

The Position of the Catholic Church in Croatia 1945 - 1970

UDK 322(497.5)’’1945/1970’’ THE POSITION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN CROATIA 1945 - 1970 Miroslav AKMADŽA* Irreconcilable standpoints After the end of World War Two, it was difficult for the Catholic Church to accept the new Yugoslav government simply because of its communist and atheistic ideology, which alone was unacceptable according to Church teach- ings. Furthermore, the Church leadership was familiar with the position of the ruling Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ - Komunistička partija Jugoslavije) on the role of the Church in society. The Church was also aware that the KPJ was under the direct influence of the communist regime in the USSR, which had mercilessly clashed with religious communities from the very moment it came to power. Therefore, there developed a fear for the future of the Catholic Church and other churches. Even before the end of the war, when it was already clear that the KPJ-led Partisan forces would take power in the coun- try, a Bishops’ conference was held in Zagreb on 24 March 1945, which issued a pastoral condemning the conduct of the Partisan movement. In the pasto- ral, the bishops strongly protested the killing of Catholic priests and believers, “whose lives were taken away in unlawful trials based upon false accusations by haters of the Catholic Church.”1 Meanwhile, among the ranks of the new government, in addition to the atheistic worldview and the influence of communist ideology from the USSR, a negative attitude developed towards all religious communities, in particular towards the Catholic Church because of its alleged negative role during World War Two. -

U.S.-Vatican Relations During the Vietnam War, 1963-1968

Abandoning the Crown: U.S.-Vatican Relations During the Vietnam War, 1963-1968 John Quinn-Isidore Russell Senior Thesis Seminar Department of History, Columbia University First Reader: Professor Elisheva Carlebach Second Reader: Professor Lien-Hang Nguyen Russell 1 Table of Contents Notes ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1: The Triple Crown ......................................................................................................................... 7 Catholicism in the United States ............................................................................................................. 10 Political Catholicism in Vietnam .............................................................................................................. 12 Chapter 2: New Wine, Old Wineskins ......................................................................................................... 17 Vatican II as Anti-Imperialist ................................................................................................................... 17 Vatican II as Detente .............................................................................................................................. -

Popes, Power, and World Politics: from Leo XIII to Benedict XVI

Popes, Power, and World Politics: From Leo XIII to Benedict XVI Pope Pius IX died in 1878. The longest-reigning pope in history spent the last eight years of his pontificate as the self-styled “prisoner of the Vatican, as the anticlerical forces of Italian reunification had incorporated the ancient Papal States into the new Kingdom of Italy. (Pius had instructed his army to fire one volley, “for honor,” and then surrender their hopeless cause.) When Pius died, fears of foreign political interference in the election of a new pope led Britain’s Cardinal Henry Edward Manning to suggest that the conclave be held in Malta, under the protective guns of the Royal Navy. Precisely one hundred years later – that is, precisely one hundred years after Leo XIII was elected pope at the lowest point in the papacy’s political fortunes in a millennium – another conclave, in 1978, elected as pope Cardinal Karol Wojtya, who would have a greater influence on the history of his times than any pontiff since the high Middle Ages. According to the now-standard histories of the Cold War, John Paul II was the pivotal figure in the collapse of European communism (an argument that was widely dismissed, in both the Catholic and secular press, when I first advanced it in 1992). But the imprint of the shoes of this fisherman can be found beyond the democracies of central and Eastern Europe; they can be found as well in the politics of Latin America, and East Asia. Moreover, John Paul’s critique of “real existing democracy” helped define the key moral issues of public life in the developed democracies and in the complex world of international institutions; here, we see his impact as recently as our own presidential primaries. -

Knights of Columbus' Relationship with the Holy See from 1882 To

Knights of Columbus’ Relationship with the Holy See From 1882 to Present Leo XIII (1878-1903) • 1895 – Archbishop (later Cardinal) Francesco Satolli, Apostolic Delegate to the United States, gives the Order a “warm approbation and apostolic blessing.” • 1903 – K of C expresses mourning at the death of the first pope of the Order’s existence by wearing purple ribbon. St. Pius X (1903-1914) • 1903 – Knights are among the first pilgrim audience of Pope Pius X and the first to greet a newly elected pontiff with the American flag. • 1903 – Early in his pontificate, Pope Pius sends a letter of encouragement to the K of C, read by Cardinal Gibbons at the 1904 Supreme Convention. • 1905 – Pope sends his blessing to the Knights at the Supreme Convention. • 1907 – The Order sends a cablegram of solidarity and support to the pope concerning the Church in France. • 1907 – The pope meets with a delegation of Knights in Sala Clementina. • 1910 – K of C plans the “largest pilgrimage which ever left America for Rome” and meets with the pope. • 1910 – Knights defend papal involvement in science by printing a special edition of James J. Walsh’s book, The Popes and Science. • 1912-16 – Archbishop (later Cardinal) Giovanni Bonzano, Apostolic Delegate to the United States, attends the Supreme Convention, with papal blessing for the Order. • 1912 – Past Supreme Knight Edward Hearn is honored by the pope with the title of Knight of St. Gregory. • 1914 – The Order collects and donates funds for Pope Pius X’s project for first scientific, scholastic, and paleographic revision of the Latin Bible since St. -

Umberto II (The Shroud During the Centuries in Humbert II’S Collection), Gribaudo, Turin, 1998, Pp

On March 18, 1983 Humbert II of Savoy died in Geneva. The most solemn obsequies took place on March 24 in Hautecombe abbey, in Savoy, where the body had been transferred privately. The announcement of the Holy Shroud donation to the Holy See in the person of the present Pope John Paul II was given in Geneva on March 25, 1983 by the lawyer Armando Radice, who read the following communiqué: “On March 23, the Count Fausto Solaro del Borgo has given to His Most Reverend Eminence, cardinal Agostino Casaroli, His Holiness’ Secretary of State, a letter of His Majesty Humbert II’s testamentary executors, His Majesty Simeon of Bulgaria and His Royal Highness the Landgrave Mauritius of Assia, by which they begged him to inform His Holiness John Paul II, that the late Monarch had ordered, in his last will and testament, that the Holy Shroud, kept in the Cathedral of Turin, was given in full property to the Supreme Pontiff. His Royal Highness, the Prince of Naples, also on behalf of his entire family, has expressed the joy of being able, respecting his august father’s will – which aims at definitively guaranteeing for the future the entrusting of one of the most precious relics of Our Lord’s Passion to the Holy See – to fulfil a devotion gesture towards the person of the Roman Church Supreme Pontiff. The Prince of Naples has decided that the late Monarch’s will could be communicated to His Holiness John Paul II on the eve of the Holy Year’s opening.” Here is the original text of the donation document as it was published by the Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy in the book La Sindone nei secoli nella collezione di Umberto II (The Shroud during the centuries in Humbert II’s collection), Gribaudo, Turin, 1998, pp.