Dolly Sods—A Brief Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papilio Glaucus, P. Marcellus, P. Philenor, Pieris Rapae, Colias Philo Dice, Antho Caris Genutia, Anaea Andria, Euptychia Gemma

102 REMINGTON: 1952 Central Season Vol.7, nos.3·4 Papilio glaucus, P. marcellus, P. philenor, Pieris rapae, Colias philo dice, Antho caris genutia, Anaea andria, Euptychia gemma. One exception to the general scarcity was the large number of Erynnis brizo and E. juvenalis which were seen clustered around damp spots in a dry branch on April 9. MERRITT counted 67 Erynnis and 2 Papilio glaucus around one such spOt and 45 Erynnis around another. Only one specimen of Incisalia henrici was seen this spring. MERRITT was pleased to find Incisalia niphon still present in a small tract of pine although the area was swept by a ground fire in 1951. Vanessa cardui appeared sparingly from June 12 on, the first since 1947. In the late summer the season appeared normal. Eurema lisa, Nathalis iole, Lycaena thoe, and Hylephila phyleus were common. Junonia coenia was more abundant around Louisville than he has ever seen it. A rarity taken in Louisville this fall was Atlides halesus, the first seen since 1948. The latest seasonal record made by Merritt was a specimen of Colias eury theme flying south very fast on December 7. EDWARD WELLING sent a record of finding Lagoa crispata on June 27 at Covington. Contributors: F. R. ARNHOLD; E. G. BAILEY; RALPH BEEBE; S. M. COX; H. V. DALY; 1. W . GRIEWISCH; J. B. HAYES; R. W. HODGES; VONTA P. HYNES; R. LEUSCHNER; J. R. MERRITT; J. H. NEWMAN; M. C. NIEL SEN; 1. S. PHILLIPS; P. S. REMINGTON; WM. SIEKER; EDWARD VOSS; W. H . WAGNER, JR.; E. C. -

Observation and a Numerical Study of Gravity Waves During Tropical Cyclone Ivan (2008)

Open Access Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 641–658, 2014 Atmospheric www.atmos-chem-phys.net/14/641/2014/ doi:10.5194/acp-14-641-2014 Chemistry © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. and Physics Observation and a numerical study of gravity waves during tropical cyclone Ivan (2008) F. Chane Ming1, C. Ibrahim1, C. Barthe1, S. Jolivet2, P. Keckhut3, Y.-A. Liou4, and Y. Kuleshov5,6 1Université de la Réunion, Laboratoire de l’Atmosphère et des Cyclones, UMR8105, CNRS-Météo France-Université, La Réunion, France 2Singapore Delft Water Alliance, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore 3Laboratoire Atmosphères, Milieux, Observations Spatiales, UMR8190, Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace, Université Versailles-Saint Quentin, Guyancourt, France 4Center for Space and Remote Sensing Research, National Central University, Chung-Li 3200, Taiwan 5National Climate Centre, Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia 6School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Melbourne, Australia Correspondence to: F. Chane Ming ([email protected]) Received: 3 December 2012 – Published in Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss.: 24 April 2013 Revised: 21 November 2013 – Accepted: 2 December 2013 – Published: 22 January 2014 Abstract. Gravity waves (GWs) with horizontal wavelengths ber 1 vortex Rossby wave is suggested as a source of domi- of 32–2000 km are investigated during tropical cyclone (TC) nant inertia GW with horizontal wavelengths of 400–800 km, Ivan (2008) in the southwest Indian Ocean in the upper tropo- while shorter scale modes (100–200 km) located at northeast sphere (UT) and the lower stratosphere (LS) using observa- and southeast of the TC could be attributed to strong local- tional data sets, radiosonde and GPS radio occultation data, ized convection in spiral bands resulting from wave number 2 ECMWF analyses and simulations of the French numerical vortex Rossby waves. -

State Game Lands 267 Blair County

ROAD CLASSIFICATION Secondary Highway Unimproved Road ! Electric Oil Pipeline; Gas Line Other Line l Phone ll Sewer Line; Water Line ± Trail !! Special Trails Stream IA Parking Area ²³F Food & Cover Crew HQ ²³G Garage L Headquarters l ²³O Other YY ²³S Storage l Gate YY Tower Site l l Food Plot Game Land Boundary Other Game Lands Wetland ! ! ! ! ! IAl! l ! ! ! ! PENNSYLVANIA GAME COMMSISSION STATE GAME LANDS 267 BLAIR COUNTY Feet 0 1900 3800 5700 7600 1 inch = 3,000 feet January 2014 Service Layer Credits: Copyright:© 2013 National Geographic Society, i-cubed State game land (SGL) 267 is located in Logan Township, Blair County 12/17/2012 SPORTSMEN'S RECREATION MAP in Wildlife Management Unit 4D and currently has a deeded acreage of 1,041 acres. Approximately 2,200 feet of Laurel Run, a cold water fishery, flows through SGL 267, and all water within this SGL is part of the Susquehanna watershed. The Game Commission currently maintains one public parking area on SGL 267, located on Skyline Drive. There are 0.95 miles of maintained administrative roads throughout SGL 267, providing for public access to this area by foot. The farthest point on SGL 267 by foot from a parking area or public road is approximately 0.75 miles. All roads are currently closed year-round to public motor vehicle traffic and access is controlled with locked gates. The gated roads and rights-of-way provide access for hunters and avenues for hiking, Each time a hunter buys a hunting license, the wildlife photography and bird-watching. money he spends goes toward many facets of wildlife management. -

Dolly the Sheep – the First Cloned Adult Animal

DOLLY THE SHEEP – THE FIRST CLONED ADULT ANIMAL NEW TECHNOLOGY FOR IMPROVING LIVESTOCK From Squidonius via Wikimedia Commons In 1996, University of Edinburgh scientists celebrated the birth of Dolly the Sheep, the first mammal to be cloned using SCNT cloning is the only technology adult somatic cells. The Edinburgh team’s success followed available that enables generation of 99.8% its improvements to the single cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) genetically identical offspring from selected technique used in the cloning process. individuals of adult animals (including sterilized animals). As such, it is being Dolly became a scientific icon recognised worldwide and exploited as an efficient multiplication tool SCNT technology has spread around the world and has been to support specific breeding strategies of used to clone multiple farm animals. farm animals with exceptionally high genetic The cloning of livestock enables growing large quantities of value. the most productive, disease resistant animals, thus providing more food and other animal products. Sir Ian Wilmut (Inaugural Director of MRC Centre for Regeneration and Professor at CMVM, UoE) and colleagues worked on methods to create genetically improved livestock by manipulation of stem cells using nuclear transfer. Their research optimised interactions between the donor nucleus and the recipient cytoplasm at the time of fusion and during the first cell cycle. Nuclear donor cells were held in mitosis before being released and used as they were expected to be passing through G1 phase. CLONING IN COMMERCE, CONSERVATION OF AGRICULTURE AND PRESERVATION ANIMAL BREEDS OF LIVESTOCK DIVERSITY Cloning has been used to conserve several animal breeds in the recent past. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2018 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2018 As of September 30, 2018 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover photo courtesy of: Chris Chavez Statistics are current as of: 10/15/2018 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,948,059 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 506 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 128 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 446 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The FS also administers several other types of nationally-designated areas: 1 National Historic Area in 1 State 1 National Scenic Research Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Recreation Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Wildlife Area in 1 State 2 National Botanical Areas in 1 State 2 National Volcanic Monument Areas in 2 States 2 Recreation Management Areas in 2 States 6 National Protection Areas in 3 States 8 National Scenic Areas in 6 States 12 National Monument Areas in 6 States 12 Special Management Areas in 5 States 21 National Game Refuge or Wildlife Preserves in 12 States 22 National Recreation Areas in 20 States Table of Contents Acreage Calculation ........................................................................................................... -

Area Information

AREA INFORMATION The area is known as the Potomac Highlands. The Allegheny Mountains run right through the region which is the highest watershed for the Potomac River, the largest river feeding into the Chesapeake Bay. The region is renowned for amazing views, high elevation blueberry and spruce stands, dense rhododendron thickets, hundreds of Brook Trout streams, and miles of backcountry trails. Much of the Potomac Highlands is within the one million acre Monongahela National Forest which features National Wilderness areas like Otter Creek, Dolly Sods, Cranberry Glades, Roaring Plains West, and Laurel Fork North. The region is ideal for hiking, rock climbing, skiing, kayaking, canoeing, fishing, and hunting which are all popular activities in the area. The Shavers Fork is a stocked trout stream and maintained by WV Division of Natural Resources, as are many other rivers in the area. Wonderful skiing can be experienced at Timberline, Canaan Valley, Whitegrass Nordic Center Ski areas and Snowshoe Mountain Resort, which are all less than 40 miles from our door. State Parks and forests in the area include Blackwater Falls, Canaan Valley, Audra, Kumbrabow, Seneca, and Cathedral. Federal Recreation areas include Spruce Knob & Seneca Rocks management area, Smoke Hole Canyon, Stuarts Recreation Area, Gaudineer Knob, and Spruce Knob Lake. The region is within 5 hours of half of the nation’s population yet offers a mountain playground second to none. Elkins deserves its high ranking in America's Best Small Art Towns. Elkins is home to Davis and Elkins College and the Augusta Heritage Arts Center, The Mountain State Forest Festival and our thriving Randolph County Community Arts Center (www.randolpharts.org). -

WV Hunting & Trapping Regulations

WEST VIRGINIA A N HUNTING D TRAPPING Regulations Summary JULY 2019 ‒ JUNE 2020 wvdnr.gov From the Director Access to viable hunting areas and land has long been identified in nationwide surveys as a limitation for those people wanting to hunt. While West Virginia has been blessed with approximately one million acres of National Forest land and another 500,000 acres of state-owned or managed land, one region of the State has had limited public land available to outdoor enthusiasts—until now! Over the past year, West Virginia Division of Natural Resources officials have partnered with The Conservation Fund to acquire 31,218 acres of public land in the west-central region of the state. These efforts have resulted in the creation of seven new wildlife management areas (WMAs), as well as expansion of three other WMAs. The new properties are in Calhoun, Doddridge, Jackson, Pleasants, Ritchie, Wirt and Wood counties. Funds from various sources were used in this land acquisition project, including hunting license monies, Wildlife Restoration Program federal funds, as well as contributions from various pipeline development companies and non-governmental organizations. I would like to thank Atlantic Coast Pipeline, LLC, Dominion Energy Transmission, Inc., and TC Energy for their monetary donations. The contributions are a result of an agreement between the pipeline development companies and the DNR to provide conservation measures for forest-dependent wildlife and their associated habitats affected as a result of development of natural pipeline projects. Our staff will manage these new lands to enhance essential wildlife habitat for a variety of forestland species. -

The Archaeological Survey of Sand Bay Pier Bois Blanc Island, Lake Huron, Michigan

The Archaeological Survey of Sand Bay Pier Bois Blanc Island, Lake Huron, Michigan Conducted By Team Members: John Sanborn, project manager/author Andrea Gauthier, data recording Donovan Alkire, researcher/author Henry Ramsby, operational officer/author INTRODUCTION The remains of a pier (loading dock) located in Sand Bay on Bois Blanc Island (BBI), Michigan, in the Straits of Mackinac, was surveyed as part of a Nautical Archeology Society (NAS) certification program in the summer of 2010. The objective of this project is to document the history and use of the pier as it related to logging from the late 1800’s to the time of its demise in 1930. The primary focus of this research is to survey the remains of the pier, both underwater and on the foreshore. A total station was used to survey two of the main crib structures, a number of pilings and submerged artifacts. Extensive photographic documentation was also produced of the site as a record of its current state. During preliminary research it was discovered that a strange tale existed surrounding the pier. In the early 1900's a narrow gauge railroad had been constructed across the island, which terminated at the end of the pier. Local folklore indicated that a Shay locomotive had either been driven off the end of the pier into Lake Huron, or had been blown up with dynamite while still on the pier. This local mystery has provided a research question to be answered by this project. The research team has set out to either prove, or disprove the legend of the Shay and the manner in which the locomotive met its demise. -

West Virginia Trail Inventory

West Virginia Trail Inventory Trail report summarized by county, prepared by the West Virginia GIS Technical Center updated 9/24/2014 County Name Trail Name Management Area Managing Organization Length Source (mi.) Date Barbour American Discovery American Discovery Trail 33.7 2009 Trail Society Barbour Brickhouse Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.55 2013 Barbour Brickhouse Spur Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.03 2013 Barbour Conflicted Desire Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 2.73 2013 Barbour Conflicted Desire Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.03 2013 Shortcut Barbour Double Bypass Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 1.46 2013 Barbour Double Bypass Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.02 2013 Connector Barbour Double Dip Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.2 2013 Barbour Hospital Loop Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.29 2013 Barbour Indian Burial Ground Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.72 2013 Barbour Kid's Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.72 2013 Barbour Lower Alum Cave Trail Audra State Park WV Division of Natural 0.4 2011 Resources Barbour Lower Alum Cave Trail Audra State Park WV Division of Natural 0.07 2011 Access Resources Barbour Prologue Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.63 2013 Barbour River Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 1.26 2013 Barbour Rock Cliff Trail Audra State Park WV Division of Natural 0.21 2011 Resources Barbour Rock Pinch Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 1.51 2013 Barbour Short course Bypass Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.1 2013 Barbour -

RCED-84-101 Private Mineral Rights Complicate the Management Of

. I*/ I/ / liiY@d BY W-- CXIMPTROLLER GENERAL ’ Report To The Congress Private Mineral Rights Complicate The Management Of Eastern Wilderness Areas Since 1975, the Congress has expanded the Natlonal Wilderness Preservatron System to areas of eastern natlonal forest lands Many of these eastern lands contain slgnlflcant amounts of private mlneral rights, as a result, the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service experienced management and legal problems In trying to preserve these lands and control private mineral development In addition, recent attempts by the federal government to acquire private mineral rights III eastern wilderness areas have caused considerable contro- versy and congressional debate because of the high costs associated with these purchases These problems could Increase because many other areas under conslderatlon for wilderness designation In the east contain private mineral rights GAO believes that consideration of private mineral rights IS Important In decldlng whether other eastern lands should be descgnated as wilderness However, the Forest Service did not provide InformatIon regarding private mineral rights and their potential acquisition costs when It submitted wilderness recommendations to the Congress In 1979 Therefore, GAO recommends that the Secretary of Agrl- culture direct the Forest Service to analyze the potential conflicts and costs associated with private mineral rights In potential wilderness areas and provide this data to the Congress In addition, GAO believes that the Congress should consider provldlng further guidance to the Forest Service by specifying what actlon should be taken regarding private rnlneral rights In eastern wilderness areas Ill11111111111124874 GAO/RCED-84-101 JULY 26, 1984 Request for copies of GAO reports should be sent to: U.S. -

Monongahela National Forest

Monongahela National Forest United States Department of Final Agriculture Environmental Impact Statement Forest Service September for 2006 Forest Plan Revision The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its program and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202)720- 2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202)720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal Opportunity provider and employer. Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Monongahela National Forest Forest Plan Revision September, 2006 Barbour, Grant, Greebrier, Nicholas, Pendleton, Pocahontas, Preston, Randolph, Tucker, and Webster Counties in West Virginia Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Monongahela National Forest 200 Sycamore Street Elkins, WV 26241 (304) 636-1800 Responsible Official: Randy Moore, Regional Forester Eastern Region USDA Forest Service 626 East Wisconsin Avenue Milwaukee, WI 53203 (414) 297-3600 For Further Information, Contact: Clyde Thompson, Forest Supervisor Monongahela National Forest 200 Sycamore Street Elkins, WV 26241 (304) 636-1800 i Abstract In July 2005, the Forest Service released for public review and comment a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) that described four alternatives for managing the Monongahela National Forest. Alternative 2 was the Preferred Alternative in the DEIS and was the foundation for the Proposed Revised Forest Plan. -

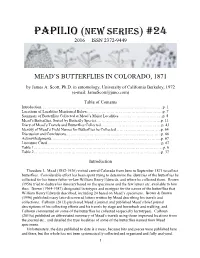

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens.