Monongahela National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain Memories

MOUNTAIN MEMORIES WILD, WONDERFUL WEST VIRGINIA YOU’LL FIND IT HERE. Why just “vacation” when you can travel? Here in the Mountain State, we get real. The best way to dig beyond the attractions and into our rich local culture is, of course, to ask a local. So we covered that for you—and man, did they have a lot to share! Get off the beaten path and onto a real adventure with this one-of-a-kind map that takes you to some of the wildest, wonderful-est and realest places around. Brought To You By KANAWHA COUNTY POPULATION: 191,275 Charleston CLAY CENTER Take in a play or Convention BRIDGE ROAD BISTRO & Visitors stretch your intellect at the Clay Nationally and regionally Bureau Center, which is dedicated to acclaimed for its cuisine and wine Visitor or promoting arts and sciences in selection, Bridge Road Bistro Welcome the Mountain State. Center supports local farmers, producers 79 and communities. HADDAD RIVERFRONT PARK 77 River With an amphitheater that seats COONSKIN PARK 119 Elk up to 2,500 spectators to lovely South Coonskin has over 1,000 acres of Charleston riverfront and downtown views, fun with hiking and biking, disc 64 Haddad Riverfront Park hosts golf and a swimming pool. Don’t 60 a variety of events, including forget to take a trip around the Coal River Live on the Levee, a free concert Charleston skate park and feed a few ducks 119 series every May-September. while you’re there. Kanawha State Forest EAST END EATERIES 60 TIPS FROM The East End is home to an eclectic Kanawha mix of eateries, including Bluegrass 77 64 River THE LOCALS Kitchen, Tricky Fish, Little India, The Red Carpet, The Empty Glass and Starling’s Coffee & Provisions. -

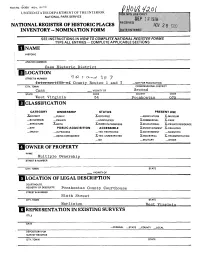

Nomination Form Location Owner Of

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTOCOMPLETE NATIONAL REG/STEP FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON Cass Historic District LOCATION STREETS. NUMBER County Routes 1 and 7 _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN Cass VICINITY OF STATE CODE CODE West Virginia 54 075 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE .XDISTRICT _PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL X-PARK —STRUCTURE X.BOTH X_WORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL X-PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE X-ENTERTAINMENT X-RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED XlNDUSTRIAL X-TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Multiple Ownership STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE _ VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Pocahontas County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Ninth Street CITY. TOWN STATE Marlinton West Virginia. TiTLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD X_ALTERED —MOVED DATE. _FAIR _ UNEXPOSED The first men who worked for the lumber company on Leatherbark Run in Pocahontas County were housed in all sorts of crude shelters. It is quite probable that those construction workers built their own pole lean-tos, brush shelters, or some type of dug-outs. Before Cass was incorporated and named in 1902, it could be that the men with families who came early to work for the company built small rough-lumber cottages off company property. -

Florida MSTA Newsletter for May 2020

The Florida Gator Tale Newsletter of the Florida Chapter of the Motorcycle Sport Touring Association June 2021 - Volume 14 Issue 6 In the June 2021 Issue: Feature Article Page 1 – Feature Article Page 9 – Safety Talk Page 11 – Florida News Page 14 – Florida Rides STAR 2021 Route Guide Page 15 – Future Florida Rides MSTA Page 16 – Florida MSTA Apparel Page 16 – Classified Ads Contact Information: South Florida Director: Van VanSteelant – [email protected] Central Florida Director: Carl Swofford – [email protected] Florida Gator Tale Editor: Kim Longacre – [email protected] For the upcoming STAR 2021 at the Canaan Valley Resort in Davis, West Virginia (June 13-16, 2021), the MSTA offers an online STAR 2021 Route Guide at http://star21.flybyweek.com/RouteGuide.html. This year, in addition to the GPX navigation files, each route includes a link to an online map image and a pdf document of the map and Garmin route that you can download. Super easy!! Here are summary descriptions of each of the 22 STAR routes in the guide: 01 River RunsThru It RouteType: TOURING BIKE-FRIENDLY Navigation difficulty: AVERAGE Distance: 196 miles. Lunch Stop: Apple Annie's near Morgantown, WV Direction from Canaan Valley: NW, N, NE, CLOCKWISE Comments: Something for big bikes, 2-up with some 1.5 lane twisty pavement to work up appetites. This route leans more towards civilization. 02 Smoke Hole to the Knob RouteType: TOURING BIKE-FRIENDLY, DESTINATION- Spruce Knob, CURVY route. Navigation difficulty: AVERAGE Distance: 179 miles. Lunch Stop: Hollow Restaurant in Franklin, WV, and Ice Cream at Moe Fatz if desired. -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

2017 Annual Report

Annual Report 2017 Seven land protection projects Completed in one year Many things made 2017 our biggest year to date: Great project partners, a staff and board that are ardently dedicated to conserving West Virginia’s special places, generous supporters, lots of patience, and WVLT’s availability to respond to multiple requests for assistance… which continue to increase with each month. These lands are now permanently protected. Yes, permanently. As in…. forever. Signed, sealed, and recorded in deed books in their respective counties. A public park for climbing, family histories, a waterfall, wildlife habitat, hiking trails, beautiful forests and streams, agricultural land: All great places that will keep West Virginia wild and wonderful. Good projects often take a long time to complete. One of 2017’s successes was in the works for five years! With conservation easements, we take our time to make sure that landowners’ wishes are clear, so that WVLT can honor them as we become stewards of the property. Properties we decide to purchase require funding sources, may involve government regulation, and sometimes need months of negotiation around boundaries, minerals, and family interests. Title exams, surveys, appraisals, maps, and environmental assessments are all part of the due diligence we undertake for every project, with full review conducted by staff, our legal team, a committee of our board of directors, and ultimately by our full Board. But enough about the anatomy of a project. What really excites us is the way that WVLT can bring its land protection skills and knowledge to others, to make something positive and lasting happen. -

WILDFLOWERS the Bulletin of the Botanical Society of Western Pennsylvania • July and August 2005

WILDFLOWERS The Bulletin of the Botanical Society of Western Pennsylvania • July and August 2005 Website for the Botanical Society of Among the florets of Thistles, attached to the top of each seed, is a ring of fine hairs, a Western Pennsylvania modified calyx called a pappus. The details of the pappus are small and require magnification. President Haywood has created a website for the The pappus and seed are dispersed by wind. Botanical Society. It can be accessed at Carduus has hairs that are straight and rough, no www.botanicalsocietyofwesternpa.org. plumes. Cirsium's are feathery, plumed. The website has information about purchasing Plumeless Thistle is Eurasian and is sparingly the Society’s book, Wildflowers of represented in Pennsylvania with two species, Pennsylvania, and presents excerpts and high- Thistle (Carduus acanthoides) and Nodding or quality images from the book. Also included Musk Thistle (C. nutans). Florets are pink to are a history of the society and a description of purple, sometimes white, from June to October various projects. for Thistle and May to August for Nodding. Our monthly meetings will resume in Plumed Thistle is native in the Northern September; the next meeting will be held Hemisphere, with about sixty species in North Monday, September 12, 2005. America. Seven species are in Pennsylvania, five native, two introduced. The two introduced Enjoy Your Wildflowers: Thistles, species are Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare) and Canada Thistle (C. arvense). Both are Part I European, naturalized in North America, bloom summer into October-November, have rose to The common name, Thistle, is used casually for purple flowers and are considered noxious numerous armored plants, not necessarily weeds. -

West Virginia Northern Flying Squirrel (WVNFS), Glauconzys Sabrinus Fuscus Five Year Status Review Appendix B — Capture Site Summaries

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — West Virginia Field Office West Virginia northern flying squirrel (WVNFS), Glauconzys sabrinus fuscus Five Year Status Review Appendix B — Capture Site Summaries Attached are the summaries for the 105 West Virginia northern flying squirrel (WVNFS), G.s. fuscus, capture sites l in West Virginia. Although biologists occasionally use live-trapping, nest boxes have been the primary tool for population surveys for the WVNFS. Biologists place transects of nest boxes in a survey area and check the boxes periodically for occupancy, typically twice each year, in fall and spring. Northern flying squirrels are nocturnal, leaving their nests to forage at night and returning during the day, which facilitates daytime nest box monitoring. The success of nest box monitoring relies on the squirrels occupying the boxes during the day of the survey. Menzel (2003) found that no WVNFS in her radio telemetry study used nest boxes (despite their availability) as den sites. All nests were either natural tree cavities (i.e. dens) or dreys (i.e. outside nests constructed of leaves, twigs, lichens, etc.). She also noted WVNFS used multiple den sites, switching nests on average every 3 days in summer, and utilizing up to 12 den sites per month in lesser quality habitat (Menzel 2000, Menzel et al. 2004). Further, the nest box monitoring program conducted by the DNR had a 2% average success rate of squirrel occupancy per box checked. These data confirm the difficulty of capturing squirrels via nest boxes and caution against relying on nest box survey results to determine occupied habitat, i.e., although a captured individual affirms presence, an empty nest box does not necessarily signify absence or unoccupied habitat. -

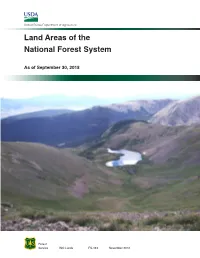

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2018 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2018 As of September 30, 2018 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover photo courtesy of: Chris Chavez Statistics are current as of: 10/15/2018 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,948,059 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 506 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 128 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 446 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The FS also administers several other types of nationally-designated areas: 1 National Historic Area in 1 State 1 National Scenic Research Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Recreation Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Wildlife Area in 1 State 2 National Botanical Areas in 1 State 2 National Volcanic Monument Areas in 2 States 2 Recreation Management Areas in 2 States 6 National Protection Areas in 3 States 8 National Scenic Areas in 6 States 12 National Monument Areas in 6 States 12 Special Management Areas in 5 States 21 National Game Refuge or Wildlife Preserves in 12 States 22 National Recreation Areas in 20 States Table of Contents Acreage Calculation ........................................................................................................... -

Area Information

AREA INFORMATION The area is known as the Potomac Highlands. The Allegheny Mountains run right through the region which is the highest watershed for the Potomac River, the largest river feeding into the Chesapeake Bay. The region is renowned for amazing views, high elevation blueberry and spruce stands, dense rhododendron thickets, hundreds of Brook Trout streams, and miles of backcountry trails. Much of the Potomac Highlands is within the one million acre Monongahela National Forest which features National Wilderness areas like Otter Creek, Dolly Sods, Cranberry Glades, Roaring Plains West, and Laurel Fork North. The region is ideal for hiking, rock climbing, skiing, kayaking, canoeing, fishing, and hunting which are all popular activities in the area. The Shavers Fork is a stocked trout stream and maintained by WV Division of Natural Resources, as are many other rivers in the area. Wonderful skiing can be experienced at Timberline, Canaan Valley, Whitegrass Nordic Center Ski areas and Snowshoe Mountain Resort, which are all less than 40 miles from our door. State Parks and forests in the area include Blackwater Falls, Canaan Valley, Audra, Kumbrabow, Seneca, and Cathedral. Federal Recreation areas include Spruce Knob & Seneca Rocks management area, Smoke Hole Canyon, Stuarts Recreation Area, Gaudineer Knob, and Spruce Knob Lake. The region is within 5 hours of half of the nation’s population yet offers a mountain playground second to none. Elkins deserves its high ranking in America's Best Small Art Towns. Elkins is home to Davis and Elkins College and the Augusta Heritage Arts Center, The Mountain State Forest Festival and our thriving Randolph County Community Arts Center (www.randolpharts.org). -

Parks, Recreation and Natural Resources Subcommittee 2014

West Virginia Legislature PARKS, RECREATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES SUBCOMMITTEE FINAL REPORT to Joint Committee on Government and Finance 2014 - 2015 Interims Members Senate House Senator William R. Laird IV, Chair Delegate Jeff Eldridge, Co-Chair Senator Clark Barnes Del. Danny Wells, Co-Chair Senator Larry Edgell Delegate Kevin Craig Senator Douglas Facemire Delegate Allen V. Evans Senator Roman Prezioso Delegate Bill Hamilton Senator Herb Snyder Delegate Brady Paxton Senator John Unger Delegate Harry Keith White Delegate Anthony Barrill Delegate Brent Boggs Speaker Tim Miley Delegate Don Perdue Delegate Mary Polling Delegate Ruth Rowan The Parks, Recreation and Natural Resources Subcommittee met each month during the 2014-2015 period beginning in May 2014 to discuss and study parks, recreation and natural resources issues. The topics assigned to the committee by the Joint Committee on Government and Finance were as follows: SCR 88- Requesting Joint Committee on Government and Finance study financial aspects of state parks’ and forest’ amenities - Study additional funding sources for state parks During the 2014 – 2015 Legislative Interim meetings, your Committee has met with the representatives of state government and the forest industry and REPORTS as follows: MAY 2014 The Parks, Recreation and Natural Resources Subcommittee met on Tuesday, May 20, 2014. Art Shomo, Wildlife Resources Section Public Information Specialist III, presented the West Virginia Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Map demonstration. Bob Beanblossom, District Administrator, Parks and Recreation Section-Management Areas, and Emily Fleming, Assistant to the Director of Natural Resources, presented an overview of SCR 89- Reassignment of five wildlife management areas to DNR. Curtis Taylor, Chief, Wildlife Resources Section- Management of Wildlife Management Areas answered various questions from members of the committee in regard to SCR 89. -

New River Crayfish Range Wide Status Assessment

New River Crayfish Range Wide Status Assessment William T. Russ, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, Division of Inland Fisheries, 645 Fish Hatchery Road, Marion, NC 28752 Zach J. Loughman, West Liberty University, Department of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Campus Service Center Box 139, West Liberty University, West Liberty, WV 26074 Roger F. Thoma, Midwest Biodiversity Institute, Inc., 4673 Northwest Parkway, Hilliard, OH 43026 Brian T. Watson, Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries, 1132 Thomas Jefferson Road, Forest, VA 24551 Todd D. Ewing, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, Division of Inland Fisheries, 1721 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, NC 27699 Abstract: The New River crayfish, (Cambarus chasmodactylus), was described in 1966 from the East Fork of the Greenbrier River, West Virginia, and historically occurred throughout the New River Basin from the Greenbrier River sub-basin in West Virginia, upstream through Virginia, and into the headwaters of the South Fork New River in North Carolina. The New River crayfish was part of a federal listing species petition in 2010 and it is cur- rently being evaluated for listing as either threatened or endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act. In order to understand the current distribution and status of this species, a range-wide assessment was undertaken by various organizations and agencies in West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina. Biological information was summarized, including species description, habitat use, life history, and current distribution. All historical and recent collections were compared and spatially displayed using GIS software. The New River crayfish was collected in three 8-digit hydrologic unit codes (HUCs) and 14 counties in three states, with the majority of occurrences in the Upper New and Greenbrier River sub-basins. -

Friends of Blackwater

Summer 2021 FRIENDS OF BLACKWATER ©Brian Peterman Working to protect West Virginia’s High Alleghenies, Blackwater River, & Blackwater Canyon. PO Box 247 - Thomas, WV 26292 - phone: 304-345-7663 - www.saveblackwater.org - [email protected] Welcoming New Faces and Saying Goodbye to Others Blackwater Watershed Project Updates A big sunny hello to all the Friends of Blackwater Canyon! My name is Jocelyn Phares, and I am a West Virginia native. I was born in Elkins and raised on the rivers of this beautiful place. Ensuring West Virginia’s public lands, waters and all the creatures depending on them are protected is truly my calling. I am thrilled to be back in my beloved home state for the first time in several years. I love our Wild and Wonderful state, and I am eager to help preserve its beauty for generations to come! In 2016, I graduated from West Virginia University with a BA in Interna- tional Studies and a minor in Global Environmental Change. In January 2021, I completed my J.D. in Portland, Oregon at Lewis and Clark Law School with a certificate in Natural Resources Law. In 2018, I externed with the World Wild- Active Treatment Planning life Fund in Wellington, New Zealand. I also clerked for Earthrise, a non-profit environmental law firm. In my final year of law school, I worked as a clerk and The plan for an active water treatment plant on the research assistant for the Global Law Alliance. The Global Law Alliance focuses North Fork is moving along. It will treat the three main on regulating the international trade of endangered species.