New River Crayfish Range Wide Status Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain Memories

MOUNTAIN MEMORIES WILD, WONDERFUL WEST VIRGINIA YOU’LL FIND IT HERE. Why just “vacation” when you can travel? Here in the Mountain State, we get real. The best way to dig beyond the attractions and into our rich local culture is, of course, to ask a local. So we covered that for you—and man, did they have a lot to share! Get off the beaten path and onto a real adventure with this one-of-a-kind map that takes you to some of the wildest, wonderful-est and realest places around. Brought To You By KANAWHA COUNTY POPULATION: 191,275 Charleston CLAY CENTER Take in a play or Convention BRIDGE ROAD BISTRO & Visitors stretch your intellect at the Clay Nationally and regionally Bureau Center, which is dedicated to acclaimed for its cuisine and wine Visitor or promoting arts and sciences in selection, Bridge Road Bistro Welcome the Mountain State. Center supports local farmers, producers 79 and communities. HADDAD RIVERFRONT PARK 77 River With an amphitheater that seats COONSKIN PARK 119 Elk up to 2,500 spectators to lovely South Coonskin has over 1,000 acres of Charleston riverfront and downtown views, fun with hiking and biking, disc 64 Haddad Riverfront Park hosts golf and a swimming pool. Don’t 60 a variety of events, including forget to take a trip around the Coal River Live on the Levee, a free concert Charleston skate park and feed a few ducks 119 series every May-September. while you’re there. Kanawha State Forest EAST END EATERIES 60 TIPS FROM The East End is home to an eclectic Kanawha mix of eateries, including Bluegrass 77 64 River THE LOCALS Kitchen, Tricky Fish, Little India, The Red Carpet, The Empty Glass and Starling’s Coffee & Provisions. -

GAULEY RIVER Ifjj

D-1 IN final wild and scenic river study ~ORA GE ' auoust 1983 GAULEY RIVER ifjJ WEST VIRGINIA PLEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL ltfFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERVICE CE'NTER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNITED S'm.TES DEPARIMENT CF 'lHE INI'ERIOR/NATICNAL PARK SERVICE As the Nation's principal conservation a· gency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environ mental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through out door recreation. The Oepartmer:t assesses our energy and min· eral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories un der U. S. administration. FINl\L REPORT GAULEY RIVER WILD AND SCENIC RIVER S'IUDY WEST VIRGINIA August 1983 Prepared by: Mid-Atlantic Regional Office National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior ,. OONTENTS I. SUMMAm' OF FINDINGS / 1 I I • CDNDUCT' OF 'llIE S'IUDY I 6 Purpose I 6 Background I 6 Study Approach I 6 Public Involvement I 7 Significant Issues / 8 Definitions of Terms Used in Report I 9 III. EVAWATION I 10 Eligibility I 10 Classification I 12 Suitcbility / 15 IV. THE RIVER ENVIOONMENT I 18 Natural Resources / 18 Cultural Resources / 29 Existing Public Use / 34 Status of Land OWnership arrl Use / 39 V. -

West Virginia Trail Inventory

West Virginia Trail Inventory Trail report summarized by county, prepared by the West Virginia GIS Technical Center updated 9/24/2014 County Name Trail Name Management Area Managing Organization Length Source (mi.) Date Barbour American Discovery American Discovery Trail 33.7 2009 Trail Society Barbour Brickhouse Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.55 2013 Barbour Brickhouse Spur Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.03 2013 Barbour Conflicted Desire Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 2.73 2013 Barbour Conflicted Desire Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.03 2013 Shortcut Barbour Double Bypass Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 1.46 2013 Barbour Double Bypass Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.02 2013 Connector Barbour Double Dip Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.2 2013 Barbour Hospital Loop Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.29 2013 Barbour Indian Burial Ground Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.72 2013 Barbour Kid's Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.72 2013 Barbour Lower Alum Cave Trail Audra State Park WV Division of Natural 0.4 2011 Resources Barbour Lower Alum Cave Trail Audra State Park WV Division of Natural 0.07 2011 Access Resources Barbour Prologue Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.63 2013 Barbour River Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 1.26 2013 Barbour Rock Cliff Trail Audra State Park WV Division of Natural 0.21 2011 Resources Barbour Rock Pinch Trail Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 1.51 2013 Barbour Short course Bypass Nobusiness Hill Little Moe's Trolls 0.1 2013 Barbour -

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park Incl

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park incl. Playground, Court & ADA Barbour County Commission $381,302 Philippi Municipal Swimming Pool City of Philippi $160,845 Dayton Park Bathhouse & Pavilions City of Philippi $100,000 BARBOUR County Total: $682,945 BERKELEY Lambert Park Berkeley County $334,700 Berkeley Heights Park Berkeley County $110,000 Coburn Field All Weather Track Berkeley County Board of Education $63,500 Martinsburg Park City of Martinsburg $40,000 War Memorial Park Mini Golf & Concession Stand City of Martinsburg $101,500 Faulkner Park Shelters City of Martinsburg $60,000 BERKELEY County Total: $709,700 BOONE Wharton Swimming Pool Boone County $96,700 Coal Valley Park Boone County $40,500 Boone County Parks Boone County $106,200 Boone County Ballfield Lighting Boone County $20,000 Julian Waterways Park & Ampitheater Boone County $393,607 Madison Pool City of Madison $40,500 Sylvester Town Park Town of Sylvester $100,000 Whitesville Pool Complex Town of Whitesville $162,500 BOONE County Total: $960,007 BRAXTON Burnsville Community Park Town of Burnsville $25,000 BRAXTON County Total: $25,000 BROOKE Brooke Hills Park Brooke County $878,642 Brooke Hills Park Pool Complex Brooke County $100,000 Follansbee Municipal Park City of Follansbee $37,068 Follansbee Pool Complex City of Follansbee $246,330 Parkview Playground City of Follansbee $12,702 Floyd Hotel Parklet City of Follansbee $12,372 Highland Hills Park City of Follansbee $70,498 Wellsburg Swimming Pool City of Wellsburg $115,468 Wellsburg Playground City of Wellsburg $31,204 12th Street Park City of Wellsburg $5,786 3rd Street Park Playground Village of Beech Bottom $66,000 Olgebay Park - Haller Shelter Restrooms Wheeling Park Commission $46,956 BROOKE County Total: $1,623,027 CABELL Huntington Trail and Playground Greater Huntington Park & Recreation $113,000 Ritter Park incl. -

Monongahela National Forest

Monongahela National Forest United States Department of Final Agriculture Environmental Impact Statement Forest Service September for 2006 Forest Plan Revision The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its program and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202)720- 2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202)720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal Opportunity provider and employer. Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Monongahela National Forest Forest Plan Revision September, 2006 Barbour, Grant, Greebrier, Nicholas, Pendleton, Pocahontas, Preston, Randolph, Tucker, and Webster Counties in West Virginia Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Monongahela National Forest 200 Sycamore Street Elkins, WV 26241 (304) 636-1800 Responsible Official: Randy Moore, Regional Forester Eastern Region USDA Forest Service 626 East Wisconsin Avenue Milwaukee, WI 53203 (414) 297-3600 For Further Information, Contact: Clyde Thompson, Forest Supervisor Monongahela National Forest 200 Sycamore Street Elkins, WV 26241 (304) 636-1800 i Abstract In July 2005, the Forest Service released for public review and comment a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) that described four alternatives for managing the Monongahela National Forest. Alternative 2 was the Preferred Alternative in the DEIS and was the foundation for the Proposed Revised Forest Plan. -

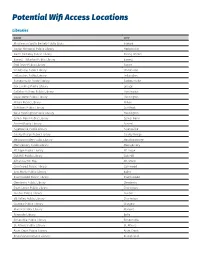

Potential Wifi Access Locations

Potential Wifi Access Locations Libraries NAME CITY Mussleman South Berkely Public Libra Inwood Naylor Memorial Public Library Hedgesville North Berkeley Public Library Falling Waters Barrett - Wharton Public Library Barrett Coal River Public Library Racine Whitesville Public Library Whitesville Follansbee Public Library Follansbee Barboursville Public Library Barboursville Cox Landing Public Library Lesage Gallaher Villiage Public Library Huntington Guyandotte Public Library Huntington Milton Public Library Milton Salt Rock Public Library Salt Rock West Huntington Public Library Huntington Center Point Public Library Center Point Ansted Public Library Ansted Fayetteville Public Library Fayetteville Gauley Bridge Public Library Gauley Bridge Meadow Bridge Public Library Meadow Bridge Montgomery Public Library Montgomery Mt Hope Public Library Mt. Hope Oak Hill Public Library Oak Hill Allegheny Mt. Top Mt. Storm Quintwood Public Library Quinwood East Hardy Public Library Baker Ravenswood Public Library Ravenswood Clendenin Public Library Clendenin Cross Lanes Public Library Charleston Dunbar Public Library Dunbar Elk Valley Public Library Charleston Glasgow Public Library Glasgow Marmet Public Library Marmet Riverside Library Belle Sissonville Public Library Sissonsville St. Albans Public Library St. Albans Alum Creek Public Library Alum Creek Branchland Outpost Library Branchland NAME CITY Fairview Public Library Fairview Mannington Public Library Mannington Benwood McMechen Public Library McMechen Cameron Public Library Cameron Sand Hill -

The Natural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2010 The aN tural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia Linh Diem Phu Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Phu, Linh Diem, "The aN tural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia" (2010). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 787. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Natural History & Distribution of Riverine Turtles in West Virginia Thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences By Linh Diem Phu Dr. Thomas K. Pauley, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Dr. Dan Evans, Ph.D. Dr. Suzanne Strait, Ph.D. Marshall University May 2010 Abstract Turtles are unique evolutionary marvels that evolved from amphibians and developed their protective shelled form more than 200 million years ago. In West Virginia, there are 10 native species of turtles, 9 of which are aquatic. Most of these aquatic turtles feed on carrion and dead plant matter, in the water and essentially "clean" our water systems. Turtles are long-lived animals with sensitive life stages that can serve as both long-term and short-term bioindicators of environmental health. With the increase in commercial trade, habitat fragmentation, degradation, destruction, there has been a marked decline in turtle species. -

Fishing Regulations JANUARY - DECEMBER 2004

WEST VIRGINIA Fishing Regulations JANUARY - DECEMBER 2004 West Virginia Division of Natural Resources D I Investment in a Legacy --------------------------- S West Virginia’s anglers enjoy a rich sportfishing legacy and conservation ethic that is maintained T through their commitment to our state’s fishery resources. Recognizing this commitment, the R Division of Natural Resources endeavors to provide a variety of quality fishing opportunities to meet I increasing demands, while also conserving and protecting the state’s valuable aquatic resources. One way that DNR fulfills this part of its mission is through its fish hatchery programs. Many anglers are C aware of the successful trout stocking program and the seven coldwater hatcheries that support this T important fishery in West Virginia. The warmwater hatchery program, although a little less well known, is still very significant to West Virginia anglers. O West Virginia’s warmwater hatchery program has been instrumental in providing fishing opportunities F to anglers for more than 60 years. For most of that time, the Palestine State Fish Hatchery was the state’s primary facility dedicated to the production of warmwater fish. Millions of walleye, muskellunge, channel catfish, hybrid striped bass, saugeye, tiger musky, and largemouth F and smallmouth bass have been raised over the years at Palestine and stocked into streams, rivers, and lakes across the state. I A recent addition to the DNR’s warmwater hatchery program is the Apple Grove State Fish Hatchery in Mason County. Construction of the C hatchery was completed in 2003. It was a joint project of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the DNR as part of a mitigation agreement E for the modernization of the Robert C. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

The Crayfishes of West Virginia's Southwestern Coalfields Region

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2013 The rC ayfishes of West Virginia’s Southwestern Coalfields Region with an Emphasis on the Life History of Cambarus theepiensis David Allen Foltz II Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Foltz, David Allen II, "The rC ayfishes of West Virginia’s Southwestern Coalfields Region with an Emphasis on the Life History of Cambarus theepiensis" (2013). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 731. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Crayfishes of West Virginia’s Southwestern Coalfields Region with an Emphasis on the Life History of Cambarus theepiensis A Thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University Huntington, WV In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Biological Sciences: Watershed Resource Science Prepared by David Allen Foltz II Approved by Committee Members: Zachary Loughman, Ph.D., Major Advisor David Mallory, Ph.D., Committee Member Mindy Armstead, Ph.D., Committee Member Thomas Jones, Ph.D., Committee Member Thomas Pauley, Ph.D., Committee Member Marshall University Defended 11/13/2013 Final Submission to the Graduate College December 2013 ©2013 David Allen Foltz II ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii AKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my gratitude to my committee members. -

Moncove Lake • Sites Are Rented on a First-Come, First-Served Basis

Renick CpN Am I g ruLes Monongahela National 64 Greenbrier Forest Camping Information River Trail • Check-out is noon. 60 White Sulphur 92 • Two motor vehicles per site. 219 Springs • One camping unit and one additional tent per site. Lewisburg 64 Moncove Lake • Sites are rented on a first-come, first-served basis. Ronceverte 60 State Park Greenbrier VIRGINIA • Camping is only permitted at designated sites. River • Hunting is not permitted within the state park. Greenbrier State Forest George Washington • Campers must register and pay at check-in. 219 National Forest • Campers should not be a nuisance or infringe on Moncove Lake the rights of others. State Park • No explosive materials or dangerous substances Union are allowed. 3 8 Gap Mills VIRGINIA • Uncased firearms, bows and arrows are prohibited. MONCOVE LAKE STATE PARK is located in Monroe Jeerson County’s Sweet Springs Valley, a lush, picturesque • A 10 mph speed limit or less is observed in LOCATION National area of West Virginia that any outdoor enthusiast campgrounds. Forest will appreciate. • Motorbikes or ATVs are prohibited. From I-64: Take the Lewisburg exit and follow U.S. Route 219 south to Union. In • No bicycle riding after dark unless lighted in front Union, take state Route 3 to Gap Mills. Then go north accom m OdATIONs and rear. on county Route 8 for approximately 6 miles. • 48 tent and trailer sites • WV state law requires bicycle riders under 15 years of age to wear a helmet. From U.S. Route 460: At Rich Creek, take U.S. Route • 25 sites with electric hookups 219 north to Union. -

Nc State Parks

GUIDE TO NC STATE PARKS North Carolina’s first state park, Mount Mitchell, offers the same spectacular views today as it did in 1916. 42 OUR STATE GUIDE to the GREAT OUTDOORS North Carolina’s state parks are packed with opportunities: for adventure and leisure, recreation and education. From our highest peaks to our most pristine shorelines, there’s a park for everyone, right here at home. ACTIVITIES & AMENITIES CAMPING CABINS MILES 5 THAN MORE HIKING, RIDING HORSEBACK BICYCLING CLIMBING ROCK FISHING SWIMMING SHELTER PICNIC CENTER VISITOR SITE HISTORIC CAROLINA BEACH DISMAL SWAMP STATE PARK CHIMNEY ROCK STATE PARK SOUTH MILLS // Once a site of • • • CAROLINA BEACH // This coastal park is extensive logging, this now-protected CROWDERSMOUNTAIN • • • • • • home to the Venus flytrap, a carnivorous land has rebounded. Sixteen miles ELK KNOB plant unique to the wetlands of the of trails lead visitors around this • • Carolinas. Located along the Cape hauntingly beautiful landscape, and a GORGES • • • • • • Fear River, this secluded area is no less 2,000-foot boardwalk ventures into GRANDFATHERMOUNTAIN • • dynamic than the nearby Atlantic. the Great Dismal Swamp itself. HANGING ROCK (910) 458-8206 (252) 771-6593 • • • • • • • • • • • ncparks.gov/carolina-beach-state-park ncparks.gov/dismal-swamp-state-park LAKE JAMES • • • • • LAKE NORMAN • • • • • • • CARVERS CREEK STATE PARK ELK KNOB STATE PARK MORROW MOUNTAIN • • • • • • • • • WESTERN SPRING LAKE // A historic Rockefeller TODD // Elk Knob is the only park MOUNT JEFFERSON • family vacation home is set among the in the state that offers cross- MOUNT MITCHELL longleaf pines of this park, whose scenic country skiing during the winter. • • • • landscape spans more than 4,000 acres, Dramatic elevation changes create NEW RIVER • • • • • rich with natural and historical beauty.