Rivett and Pilossof, 'Imagining Change, Imaginary Futures' (Ray)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central African Examiner, 1957-19651

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Zambezia (1996), XXIII (ii). THE CENTRAL AFRICAN EXAMINER, 1957-19651 ANTHONY KING2 St Antony's College, Oxford, UK Abstract The Central African Examiner is a well known source for the study of Zimbabwean history in the seminal period 1957-1965, although the story of its foundation and the backroom manoeuvrings which dogged its short life are relatively unknown. Its inception was the result of industry attempting to push the Federal Government into implementing partnership in a practical way. Up to 1960, the Examiner's internal politics mirrored this conflict, and it was during this time that the Examiner's position as a critical supporter of Government policy was at its most ambiguous. After 1960, the Examiner became a more forthright Government critic — indeed by 1964, it was the only medium left for the expression of nationalist opinion. INTRODUCTION IN THE WAKE of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in Rhodesia on 11 November 1965, censorship was imposed on the press. Most newspapers and magazines appeared with a number of blank spaces which would have been filled with articles had they not fallen foul of the censors. One magazine had so much of its content for the December 1965 issue banned that it resorted to making it a 'Do-It-Yourself edition, urging readers to fill in the blanks themselves. -

A Crucial Watershed in Southern Rhodesian Politics

A crucial watershed in Southern Rhodesian politics The 1961 Constitutional Process and the 1962 General Election E v e n t u e Högskolan på Gotlandll fi 2011 VTg ”Kandidatuppsats”u Författare: Jan Olssonr / Avdelningen för Historiab Handledare: Erik Tängerstadil d ( 1 F o r m a t Abstract The thesis examines the political development in Southern Rhodesia 1960-1962 when two processes, the 1961 Constitutional process and the 1962 General Election, had far- reaching consequences for the coming twenty years. It builds on a hypothesis that the Constitutional process led to a radicalisation of all groups, the white minority, the African majority and the colonial power. The main research question is why the ruling party, United Federal Party (UFP) after winning the referendum on a new Constitution with a wide margin could lose the ensuing election one year later to the party, Rhodesian Front (RF) opposing the constitution. The examination is based on material from debates in the Legal Assembly and House of Commons (UK), minutes of meetings, newspaper articles, election material etc. The hypothesis that the Constitutional process led to a radicalization of the main actors was partly confirmed. The process led to a focus on racial issues in the ensuing election. Among the white minority UFP attempted to develop a policy of continued white domination while making constitutional concessions to Africans in order to attract the African middle class. When UFP pressed on with multiracial structural reforms the electorate switched to the racist RF which was considered bearer of the dominant settler ideology. Among the African majority the well educated African middleclass who led the Nationalist movement, changed from multiracial reformists in late 1950‟s to majority rule advocates. -

Race, Identity, and Belonging in Early Zimbabwean Nationalism(S), 1957-1965

Race, Identity, and Belonging in Early Zimbabwean Nationalism(s), 1957-1965 Joshua Pritchard This thesis interrogates traditional understandings of race within Zimbabwean nationalism. It explores the interactions between socio-cultural identities and belonging in black African nationalist thinking and politics, and focuses on the formative decade between the emergence of mass African nationalist political parties in 1957 and the widespread adoption of an anti- white violent struggle in 1966. It reassesses the place of non-black individuals within African anti-settler movements. Using the chronological narrative provided by the experiences of marginal non-black supporters (including white, Asian, coloured, and Indian individuals), it argues that anti-colonial nationalist organisations during the pre-Liberation War period were heavily influenced by the competing racial theories and politics espoused by their elite leadership. It further argues that the imagined future Zimbabwean nations had a fluid and reflexive positioning of citizens based on racial identities that changed continuously. Finally, this thesis examines the construction of racial identities through the discourse used by black Zimbabweans and non-black migrants and citizens, and the relationships between these groups, to contend that race was an inexorable factor in determining belonging. Drawing upon archival sources created by non-black 'radical' participants and Zimbabwean nationalists, and oral interviews conducted during fieldwork in South Africa and Zimbabwe in 2015, the research is a revisionist approach to existing academic literature on Zimbabwean nationalism: in the words of Terence Ranger, it is not a nationalist history but a history of nationalism. It situates itself within multiple bodies of study, including conceptual nationalist and racial theory, the histories of marginal groups within African nationalist movements, and studies of citizenship and belonging. -

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Cohen, Andrew and Pilossof, Rory (2017) Big Business and White Insecurities at the End of Empire in Southern Africa, c.1961-1977. Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 45 (5). pp. 777-799. ISSN 0308-6534. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2017.1370217 Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/60732/ Document Version Author's Accepted Manuscript Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Big Business and White Insecurities at the End of Empire in Southern Africa, c.1961- 1977 Andrew Cohen School of History, University of Kent, Canterbury, United Kingdom and the International Studies Group, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa Rory Pilossof Department of Economics, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa Abstract This paper examines popular and widespread mistrust of large-scale capitalism, and its potential for disloyalty to the post-1965 Rhodesian state, by the white middle class and small- scale capitalists in Rhodesia. -

The Salisbury Talks

56 THE SALISBURY TALKS JOHN REED Lecturer in English at the University College of Rhodesia and Njasaland Co-Editor of 'Dissent' WHAT was remarkable about the February Constitutional Conference in Salisbury was not its initial outcome, but the fact that it took place at all. It was remarkable that Sir Edgar was so ready to accept delegates from the National Democratic Party, He had directly rejected the representation of the N.D.P. when he was composing his delegation for the Federal Conference. Then he had changed his mind and taken them with him to London. There he excluded them from the abortive territorial talks. It was also in some ways remarkable that the National Demo cratic Party leaders were so ready to attend. They ran serious risks in doing so, as we shall see. They refused directly to accept Sir Edgar as chairman of the preliminary discussions before the arrival of Mr. Duncan Sandys. Then, when Sir Edgar was firm, they gave way. They demanded that the detainees still held under the Preventive Detention Act be released before the Conference began and were under the impression that this had been promised them. All the detainees were not released, and Sir Edgar main tained he had never given any assurance that they would be. But the N.D.P. delegation attended nonetheless. It was remarkable, when you come to think of it, that Sir Edgar should sit down under the chairmanship of Mr. Duncan Sandys to plan the future of Southern Rhodesia with Mr. Joshua Nkomo, President of the N.D.P. -

Southern Rhodesia Explodes

63 SOUTHERN RHODESIA EXPLODES ENOCH DUMBUTSHENA Southern Rhodesian Journalist and Member of the National Democratic Party Two weeks after telling the settlers that "no one in Southern Rhodesia need be afraid that what has happened in the Congo could possibly happen here", the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, Sir Edgar Whitehead, called all able-bodied white men to join a new army reserve and a special constabulary. These will form new security forces to maintain peace and order, or, in other words, to suppress any future African riots. Sir Roy Welensky, Federal Prime Minister, has called upon Europeans to join the three European divisions of a new army inspired by the riots in the Congo. The Federal Government will spend an additional £3 million on this army and on equipment. None of the three territories of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland spends as much as £3 million on African education. Last year Southern Rhodesia spent only £2,641,000 on African education. It is interesting to note that Sir Roy's three white divisions were the first indication that the army is now being organized for the defence of white people against Africans in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Two years ago Sir Roy Welensky spoke of a "Boston Tea Party" should the Federation fail to get its independence; and it can be assumed that he meant by that the possibility of some settler rebellion against Great Britain. Now the army and the police, in the name of maintaining peace and order, will be used to keep the Africans down. -

Brian Blancharde

© University of the West of England Do not reproduce or redistribute in part or whole without seeking prior permission from the Rhodesian Forces oral history project coordinators at UWE Brian Blancharde Born in the UK. Joined the RAF Regiment 1952-1954 nd served in Egypt. Joined Federal Army (in Rhodesia) 1954-1959. Subsequently taught at schools in the UK, Southern Rhodesia and Zambia. Left Zambia for the UK in 1972 to undertake an MEd degree. This is Annie Bramley, interviewing Brian Blancharde on Wednesday 7th January 2009. Thank you very much for your time today and agreeing to be interviewed. Could you start by explaining how you came to be in Rhodesia, and when that was? For my National Service in the UK, 1952-54, I was in the RAF Regiment, which is effectively a private army of the Royal Air Force. My grandfather, my maternal grandfather, had fought with the Imperial Forces in the Anglo-South African war of 1899-1902 and he had been captured by the Boers effectively, with whom he became extremely friendly. He had a lot of time for the Afrikaners and he taught me my first words of Afrikaans in the unlikely setting of an English village, Long Ashton, just outside Bristol. I suppose I was infected by that and it transpired that in the Suez Canal zone, which is where I was stationed with the RAF Regiment, we ran into something called the Rhodesian African Rifles. There were about four hundred Rhodesian troops in the Canal Zone, white and black although obviously it was mainly a black battalion with white Officers. -

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland Under a Fulbright Grant

50 cents AFRICCA TODAY PAMN PHLET%*# The FEDERATION of RHODESIAand NYASALAND: THE CONTRIBUTORS CHANNING B. RICHARDSON is Professor of Government at Hamilton College, New York. During 1957-58 he lived in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland under a Fulbright Grant. A graduate of Amherst College and Columbia Uni versity, Dr. Richardson directed a displaced persons camp in Germany and Arab refugee camps in Palestine. He has written articles for the Foreign Policy Association, Africa South, etc. M. IV. KANYAMA CHIUME was born in Nyasaland in 1929. He attended Makerere College in Uganda and taught in a mission school in Tanganyika. He returned to Nyasaland in 1954 and was elected to the Nyasaland Legisla tive Council. In 1958 he became publicity secretary of the Nyasaland African Congress and attended the All-African People's Conference in Ghana. He was in Mombasa when the emergency was declared in Nyasaland and has since travelled widely in Africa, Europe, and the United States pleading the cause of self-government for Nyasaland. Guy CLUTTON-BROCK was born in 1906 and graduated from Cambridge Uni versity. He was director of several London social settlements before going to Africa. For a decade beginning in 1949 he was director of agricultural and village development at St. Faith's Mission, Rusape, Southern Rhodesia. In February, 1959, he was imprisoned for a month under the emergency regula tions of Southern Rhodesia. He is chairman of the Southern Rhodesia De tainees Legal Aid and Welfare Fund and representative of the African Devel opment Trust in Central Africa. He is author of the new book, "Dawn in Nyasaland," published by Hodder and Stoughton in England. -

Nusa 1 9 6 7 0 3

Southern Africa News Bulletin Southern Africa News Bulletin 1. - r 20, .l 0 RHODES IA RG reported exports $293.2m and imports $235.8 m 1966 -- resulting in $57.4 m positive balance of trade. Exports dropped $168 m since 1965 -probably indication of effect of tobacco sanctions. Mnite population increased by 2,000 to 226,000. African population statistics were notgiven. New York Times 4/14 In 16 months since UDI Rhodesia has maintained apparent material prosperity; but prices and unemployment rise while growth rate decreases. Yet belief is almost unanimous that RG can survive sanctions campaign. Lack of growth causes unemployment. 80,000 African school dropouts entered labor market 1966. Total employment in 1965 was 721,500, of whom 633,000 were Africans. Wash. Post 4/10 If Rhodesian illegal independence ends, probably will Mme when SA bankers tire of honoring currency worthless nearly everywhere else, or when SAG hints privately that game is up. Some Salisbury merchants report that checks mailed to SA have been returned with request for payment in another currency. W.P. 4/11 President of RTA Heurtley warned further cut in tobacco crop target 1967/68 season'would ruin hundreds of growers. In recent years average crop has been c. 250 m lbs. 1967/68 figure probably will be much below 1966/67 figure of 200 m lbs. London Times 4/12 HAG is under pressure to ask for increased sanctions. Careful study is being given to this. New sanctions might fall on passports, freedom to travel outside Southern Africa, and posts and communications; which have not been applied so far, because "they might hurt Britain's friends (black and white) in Rhodesia and prove inhumane in special cases, with political repercussions". -

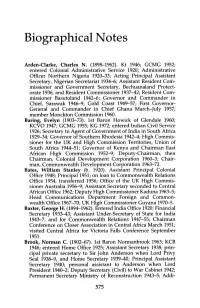

Biographical Notes

Biographical Notes Arden-Oarke, Charles N. (1898-1962). Kt 1946; GCMG 1952; entered Colonial Administrative Service 1920; Administrative Officer Northern Nigeria 1920-33; Acting Principal Assistant Secretary, Nigerian Secretariat 1934-6; Assistant Resident Com- missioner and Government Secretary, Bechuanaland Protect- orate 1936, and Resident Commissioner 1937-42; Resident Com- missioner Basutoland 1942-6; Governor and Commander in Chief, Sarawak 1946-9, Gold Coast 1949-57; First Governor- General and Commander in Chief Ghana March-July 1957; member Monckton Commission 1960. Baring, Evelyn (1903-73). 1st Baron Howick of Glendale 1960; KCVO 1947; GCMG 1955; KG 1972; entered Indian Civil Service 1926; Secretary to Agent of Government of India in South Africa 1929-34; Governor of Southern Rhodesia 1942-4; High Commis- sioner for the UK and High Commission Territories, Union of South Africa 1944-51; Governor of Kenya and Chairman East African High Commission 1952-9; Deputy-Chairman, then Chairman, Colonial Development Corporation 1960-3; Chair- man, Commonwealth Development Corporation 1963-72. Bates, William Stanley (b. 1920). Assistant Principal Colonial Office 1948; Principal 1951; on loan to Commonwealth Relations Office 1954, transferred 1956; Office of the UK High Commis- sioner Australia 1956-9; Assistant Secretary seconded to Central African Office 1962; Deputy High Commissioner Kaduna 1963-5; Head Communications Department Foreign and Common- wealth Office 1967-70; UK High Commissioner Guyana 1970-5. Baxter, George H. (1894-1962). Entered India Office 1920; Financial Secretary 1933-43; Assistant Under-Secretary of State for India 1943-7, and for Commonwealth Relations 1947-55; Chairman Conference on Closer Association in Central Africa March 1951; visited Central Africa for Victoria Falls Conference September 1951. -

Nuzn 1 9 8 4

.... Zimbabwe News .... Zimbabwe News AND Official Organ of ZANU(PF) Z Department of Information and Publicity. 14 Austin Road. Workington, C (i. sates tax) -arare. Volume 15 No. 1 Registered at the G.P.O. as a Newspaper _70 ___n._ salestax) Au. A As a s V @ A 198 TH TI TRAN ORMTIO ,V:A4=(KATLA1 WI ;1-1 M VA ri-! I Lei Contents Editorial Letters to the Editor The Party National Affairs The Party's Government International Solidarity Zimbabwe's Struggie. The Road to Lancaster ............................................................................................................................... ZANU (PF) 1980 to 1983: Party Organisation by Comrade M. Nyagumbo .................................................. 5 Restructuring and Transforming the Party Matabeleland Provincial Party Congress ...............' 7 Matabeleland North Women's Congress ................ '8 Matabeleland Women's League Meeting ................ 9 Harare Provincial Report. by Com rade D.Karim anzira ....................................................... 10 The Press: Yesterday and Today by Comrade F.Munyuki ......................................... 12 N atio nal E nem ies ........................................................................ 12 Zaka: The Pride of Masvingo ........................................... 16 Phenomenal Developments in Education: 19801983 and Beyond by Comrade Culverwell .......... 19 The Zimbabwe National Army: Taking Stock of its Role by Comrade S. Sekeramayi ......................... 23 Romania: 65th Anniversary ............................................... -

Africa South in Exile

Africa South In Exile http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.ASOCT60 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Africa South In Exile Alternative title Africa South Author/Creator Ronald M. Segal; Papas; Dennis Kiley; Gask; Alan Rake; Hannah Stanton; Norman Phillips; L. J. Blom-Cooper; Rev. Michael Scott; Chikomuami Mahala; Joao Cabral; Enoch Dumbutshena; Hon. R. S. Garfield Todd; Denis Grundy; Colin Legum; Peter de Francia; Frank Barber; R. W. Kawawa; Akin Mabogunje; Basil Davidson; Henry Lee Moon; David Miller; Gervase Matthew;