Copyrighted Material Not for Distribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and Feathered Amerindians

Colonial Latin American Review ISSN: 1060-9164 (Print) 1466-1802 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccla20 Seeking Indianness: Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and feathered Amerindians Elizabeth Hill Boone To cite this article: Elizabeth Hill Boone (2017) Seeking Indianness: Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and feathered Amerindians, Colonial Latin American Review, 26:1, 39-61, DOI: 10.1080/10609164.2017.1287323 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2017.1287323 Published online: 07 Apr 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 82 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccla20 Download by: [Library of Congress] Date: 21 August 2017, At: 10:40 COLONIAL LATIN AMERICAN REVIEW, 2017 VOL. 26, NO. 1, 39–61 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2017.1287323 Seeking Indianness: Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and feathered Amerindians Elizabeth Hill Boone Tulane University In sixteenth-century Europe, it mattered what one wore. For people living in Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Italy, clothing reflected and defined for others who one was socially and culturally. Merchants dressed differently than peasants; Italians dressed differently than the French.1 Clothing, or costume, was seen as a principal signifier of social identity; it marked different social orders within Europe, and it was a vehicle by which Europeans could understand the peoples of foreign cultures. Consequently, Eur- opeans became interested in how people from different regions and social ranks dressed, a fascination that gave rise in the mid-sixteenth century to a new publishing venture and book genre, the costume book (Figure 1). -

"Comments on the Historicity of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and the Toltecs" by Michael E

31 COMMENTARY "Comments on the Historicity of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and the Toltecs" by Michael E. Smith University at Albany, State University of New York Can we believe Aztec historical accounts about Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and other Toltec phenomena? The fascinating and important recent exchange in the Nahua Newsletter between H. B. Nicholson and Michel Graulich focused on this question. Stimulated partly by this debate and partly by a recent invitation to contribute an essay to an edited volume on Tula and Chichén Itzá (Smith n.d.), I have taken a new look at Aztec and Maya native historical traditions within the context of comparative oral histories from around the world. This exercise suggests that conquest-period native historical accounts are unlikely to preserve reliable information about events from the Early Postclassic period. Surviving accounts of the Toltecs, the Itzas (prior to Mayapan), Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tula, and Chichén Itzá all belong more to the realm of myth than history. In the spirit of encouraging discussion and debate, I offer a summary here of my views on early Aztec native history; a more complete version of which, including discussion of the Maya Chilam Balam accounts, will be published in Smith (n.d.). I have long thought that Mesoamericanists have been far too credulous in their acceptance of native historical sources; this is an example of what historian David Fischer (1970:58-61) calls "the fallacy of misplaced literalism." Aztec native history was an oral genre that employed painted books as mnemonic devices to aid the historian or scribe in their recitation (Calnek 1978; Nicholson 1971). -

4.0 a Guide to Warrior Suits 4.1 the Basic Feather Costume

4.0 A GUIDE TO WARRIOR SUITS Here follows a broad outline of the various warrior suits that were known to be associated with the Aztecs. It should be noted that all of these showy feather suits were available to the noblemen only, and could never be worn by the common man. The prime source of information for the following chapter is from the tribute lists in the Codex Mendoza and the Matricula de Tributos, the suit and banner lists in the Primeros Memoriales plus some commentary in Duran's Book of the Gods, History of the Indies and some of the Florentine Codex. The first two give clear examples of many different types of war suits, as well as a defined list of warrior and priest suits with their associated rank. Unfortunately they do not show all the suit types possible, nor do they explain what several of the suit types sent in tribute were for. Trying to mesh these sources is not neat, and some interpretation is required. While Chapter 3 examined the tribute from various provinces on a province by province basis, this chapter concentrates only on the warrior suit types as individual topics. The Mendoza Noble Warrior List (Section 4.2) and Priest Warrior List (Section 4.3) are further expanded upon with information from the tribute lists and then any other primary sources with relevant information or images. These lists are then followed up by a list of suit types not covered by either of these two lists (Section 4.4.) This section of the documentation does not cover the organisational or ranking levels of the suits except as a method for listing the suits for discussion. -

Origins of the Canaanite Alphabet and West Semitic Consonants' Inventory

DOI 10.30842/alp2306573715317 ORIGINS OF THE CANAANITE ALPHABET AND WEST SEMITIC CONSONANTS’ INVENTORY A. V. Nemirovskaya St. Petersburg State University, St. Petersburg [email protected] Abstract. It has been not infrequently mentioned by Semitists that a few graphemes of the West Semitic consonantal alphabet had been multifunctional. This is witnessed, in particular, by transcriptions of Biblical names in Septuagint, Demotic transcriptions of Aramaic as well as by the Arabic alphabet, Aramaic by its origin, which twen- ty two graphemes were ultimately developed into twenty eight ones through inventing additional diacritics. The oldest firmly deciphered and convincingly interpreted variety of the West Semitic consonantal script was employed in Ugarit as early as the 13th century BC. Being contemporaneous with the epoch of the invention of the West Semitic consonantal script the most significant evidence is provided with Se- mitic words occasionally transcribed in Egyptian papyri from the New Kingdom. Examples collected (J. Hoch) demonstrate that one and the same Semitic consonant could be recorded variously with different Egyptian consonants used; even more crucial is that various Semitic consonants could be recorded with the same Egyptian one. E. de Rougé was the first one to state that the immediate proto- types of Semitic letters were to be sought among the Hieratic char- acters. W. Helck and K.-Th. Zauzich determined that the West Se- mitic alphabet comprised only those characters which had been used in “Egyptian syllabic writing”. Summarizing philological and histori- cal evidence does allow us to conclude that the Canaanite consonantal alphabet developed as a local adaptation of the Egyptian scribal prac- tice of recording non-Egyptian words. -

The Origin of the Alphabet: an Examination of the Goldwasser Hypothesis

Colless, Brian E. The origin of the alphabet: an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis Antiguo Oriente: Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Vol. 12, 2014 Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: Colless, Brian E. “The origin of the alphabet : an examination of the Goldwasser hypothesis” [en línea], Antiguo Oriente : Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente 12 (2014). Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/revistas/origin-alphabet-goldwasser-hypothesis.pdf [Fecha de consulta:..........] . 03 Colless - Alphabet_Antiguo Oriente 09/06/2015 10:22 a.m. Página 71 THE ORIGIN OF THE ALPHABET: AN EXAMINATION OF THE GOLDWASSER HYPOTHESIS BRIAN E. COLLESS [email protected] Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand Summary: The Origin of the Alphabet Since 2006 the discussion of the origin of the Semitic alphabet has been given an impetus through a hypothesis propagated by Orly Goldwasser: the alphabet was allegedly invented in the 19th century BCE by illiterate Semitic workers in the Egyptian turquoise mines of Sinai; they saw the picturesque Egyptian inscriptions on the site and borrowed a number of the hieroglyphs to write their own language, using a supposedly new method which is now known by the technical term acrophony. The main weakness of the theory is that it ignores the West Semitic acrophonic syllabary, which already existed, and contained most of the letters of the alphabet. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

Encounter with the Plumed Serpent

Maarten Jansen and Gabina Aurora Pérez Jiménez ENCOUNTENCOUNTEERR withwith thethe Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica Preface Encounter WITH THE plumed serpent i Mesoamerican Worlds From the Olmecs to the Danzantes GENERAL EDITORS: DAVÍD CARRASCO AND EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Apotheosis of Janaab’ Pakal: Science, History, and Religion at Classic Maya Palenque, GERARDO ALDANA Commoner Ritual and Ideology in Ancient Mesoamerica, NANCY GONLIN AND JON C. LOHSE, EDITORS Eating Landscape: Aztec and European Occupation of Tlalocan, PHILIP P. ARNOLD Empires of Time: Calendars, Clocks, and Cultures, Revised Edition, ANTHONY AVENI Encounter with the Plumed Serpent: Drama and Power in the Heart of Mesoamerica, MAARTEN JANSEN AND GABINA AURORA PÉREZ JIMÉNEZ In the Realm of Nachan Kan: Postclassic Maya Archaeology at Laguna de On, Belize, MARILYN A. MASSON Life and Death in the Templo Mayor, EDUARDO MATOS MOCTEZUMA The Madrid Codex: New Approaches to Understanding an Ancient Maya Manuscript, GABRIELLE VAIL AND ANTHONY AVENI, EDITORS Mesoamerican Ritual Economy: Archaeological and Ethnological Perspectives, E. CHRISTIAN WELLS AND KARLA L. DAVIS-SALAZAR, EDITORS Mesoamerica’s Classic Heritage: Teotihuacan to the Aztecs, DAVÍD CARRASCO, LINDSAY JONES, AND SCOTT SESSIONS Mockeries and Metamorphoses of an Aztec God: Tezcatlipoca, “Lord of the Smoking Mirror,” GUILHEM OLIVIER, TRANSLATED BY MICHEL BESSON Rabinal Achi: A Fifteenth-Century Maya Dynastic Drama, ALAIN BRETON, EDITOR; TRANSLATED BY TERESA LAVENDER FAGAN AND ROBERT SCHNEIDER Representing Aztec Ritual: Performance, Text, and Image in the Work of Sahagún, ELOISE QUIÑONES KEBER, EDITOR The Social Experience of Childhood in Mesoamerica, TRACI ARDREN AND SCOTT R. HUTSON, EDITORS Stone Houses and Earth Lords: Maya Religion in the Cave Context, KEITH M. -

Physical Anthropology and the “Sumerian Problem”

Studies in Historical Anthropology, vol. 4:2004[2006], pp. 145–158 Physical anthropology and the “Sumerian problem” Arkadiusz So³tysiak Department of Historical Anthropology Institute of Archaeology, Warsaw University, Poland It is already 35 years since Andrzej Wierciñski has published his only paper on the physical anthropology of ancient Mesopotamia (1971). This short article was written in Polish and concerned a topic which has for many years been considered as very important by the international community of archaeologists and philologists, and especially by the scholars studying the ethnic history of Mesopotamia. This topic was usually called the “Sumerian problem”, and may be summarised as the speculations about the origin of Sumerians, the ethnic group which was universally considered to be the founder of the Mesopotamian civilisation. Research on the origins of the Sumerians was accidental in Professor Wierciñski’s studies, though it may be included in the larger series of his papers concerning the problems of ethnogenesis (eg. 1962, 1973, 1978). In spite of this marginality, it was perhaps the most exhaustive contribution of a physical anthropologist to the discussion about the “Sumerian problem” and for that reason it seems to be a good starting point for an essay about the contribution of physical anthropology to the research on the history of Mesopotamia. * * * The Sumerians were the first known ethnic group inhabiting Mesopotamia. It does not mean that they must have been the first settlers in that region, but is the simple result of the fact that it was they who had invented the system of writing and thus were able to make their ethnicity known to modern scholars. -

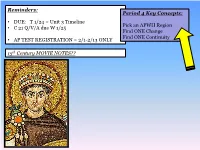

T 1/24 = Unit 3 Timeline • C 21 Q/V/A Due W 1/25 • AP TEST

Reminders: Period 4 Key Concepts: • DUE: T 1/24 = Unit 3 Timeline Pick an APWH Region • C 21 Q/V/A due W 1/25 Find ONE Change Find ONE Continuity • AP TEST REGISTRATION = 2/1-2/13 ONLY 15th Century MOVIE NOTES?? Unit 3: SAQs……. Roots VS Routes? Byzantine Empire/Western Europe Islam MUST know correct location of the historical developments that you are discussing! 1. a) Identify and explain one economic impact Islamic traders had on sub-Saharan Africa. b) Identify and explain one cultural influence Islamic traders had on sub-Saharan Africa. c) Identify and explain one example of where local sub-Saharan cultures resisted assimilation with Islam. a) Specific examples! : salt, gold, slaves, horses, spices, domestication of camels, camel saddles cultural diffusion of Islam (Mansa Musa was NOT an Islamic trader) : THEN explain how the above specifically influenced the economy of sub-Saharan Africa b) Specific examples!: cultural diffusion of Islam = Five Pillars of Faith practiced, use of the Quran, 5 prayers a day, inspired to go on the hajj Conversion of merchants to Islam THEN WHY? Did Islamic traders influence culture in that way? c) Resistance to Islam: Axum, not wearing the veil, Bantu (WHY is that an example of resistance to Islam?) 2. a) Identify and explain one reason for the change in Byzantine territory between 565 CE and 1025 CE b) Identify an explain one way that geography/interaction with the environment influenced the economic development of the Byzantine Empire c) Identify and explain one way that geography/interaction with the environment influenced the economic development of Western Europe between 600-1450 CE. -

Classroom Activity Pictorial Language: Mesoamerican Reading

Classroom Activity Pictorial Language: Mesoamerican Reading and Writing ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Enduring Understanding The basic unit of pictorial language is the pictogram, a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept. Pictorial language, although an ancient tradition, is still employed in colloquialisms today. Grades K–12 Time One class period Visual Art Concepts Symbol, meaning, representation, communication, Materials Paper and pencils. Optional: colored pencils Talking about Art Pictorial language, or an ideographic writing system is a method of communication based on the ideogram/pictogram. An ideogram is a symbol that represents an idea or concept, while a pictogram conveys meaning through realistic resemblance. These symbols, unique to every ancient civilization, formed a hieroglyphic dictionary for Mesoamerican scribes. Much of the history of Mesoamerica can be traced through their pictorial language, independently developed around 950 and widely adopted throughout southern Mexico by 1300. It was used to record and preserve the history, genealogy, and mythology of Mixtec, Nahua, and Zapotec cultures and appears most prominently in painted books called codices. (For more information about codices and for tips on how to create one, see the accompanying lesson plan Create Your Lord Eight Deer Own Codex.) View and discuss the Codex Nuttal, Mexico, Western Oaxaca, 15th–16th century. What is going on here? Who are the characters? What is the setting? What action is taking place? How did the scribe or artist use line, shape, space, color, and composition to tell the story? This codex tells the story of Lord Eight Deer, an epic Mixtec conqueror and cult hero who lived between 1063 and 1115. -

Rethinking the Conquest : an Exploration of the Similarities Between Pre-Contact Spanish and Mexica Society, Culture, and Royalty

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2015 Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2015 Samantha Billing Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Billing, Samantha, "Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty" (2015). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 155. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/155 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by SAMANTHA BILLING 2015 All Rights Reserved RETHINKING THE CONQUEST: AN EXPLORATION OF THE SIMILARITIES BETWEEN PRE‐CONTACT SPANISH AND MEXICA SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND ROYALTY An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa May 2015 ABSTRACT The Spanish Conquest has been historically marked by the year 1521 and is popularly thought of as an absolute and complete process of indigenous subjugation in the New World. Alongside this idea comes the widespread narrative that describes a barbaric, uncivilized group of indigenous people being conquered and subjugated by a more sophisticated and superior group of Europeans. -

The Cult of the Book. What Precolumbian Writing Contributes to Philology

10.3726/78000_29 The Cult of the Book. What Precolumbian Writing Contributes to Philology Markus Eberl Vanderbilt University, Nashville Abstract Precolumbian people developed writing independently from the Old World. In Mesoamerica, writing existed among the Olmecs, the Zapotecs, the Maya, the Mixtecs, the Aztecs, on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and at Teotihuacan. In South America, the knotted strings or khipus were used. Since their decipherment is still ongoing, Precolumbian writing systems have often been studied only from an epigraphic perspective and in isolation. I argue that they hold considerable interest for philology because they complement the latter’s focus on Western writing. I outline the eight best-known Precolumbian writing systems and de- scribe their diversity in form, style, and content. These writing systems conceptualize writing and written communication in different ways and contribute new perspectives to the study of ancient texts and languages. Keywords Precolumbian writing, decipherment, defining writing, authoritative discourses, canon Introduction Written historical sources form the basis for philology. Traditionally these come from the Western world, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Few classically trained scholars are aware of the ancient writing systems in the Americas and the recent advances in deciphering them. In Mesoamerica – the area of south-central Mexico and western Central America – various societies had writing (Figure 1). This included the Olmecs, the Zapotecs, the people of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Maya, Teotihuacan, Mix- tecs, and the Aztecs. In South America, the Inka used knotted strings or khipus (Figure 2). At least eight writing systems are attested. They differ in language, formal structure, and content.