“PHONETIC UNITY in the DIALECT of a SINGLE VILLAGE” Louis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrain À Bâtir Quartier Résidentiel Calme

TERRAIN À BÂTIR QUARTIER RÉSIDENTIEL CALME ESTAVAYER-LE-LAC LES ESSERPIS – PARCELLE N° 2236 DOCUMENTATION DE VENTE Parcelle N° 2236 ESTAVAYER-LE-LAC Les Esserpis, Estavayer-le-Lac Estavayer-le-lac est situé légèrement élevé Connexion garantie – la parcelle 2236 est sur la rive sud du lac de Neuchâtel. située dans un quartier calme et familial. Près L'emplacement optimal du trafic, le centre du centre, près de la gare routière (200m). historique et la multitude d'attractions Les transports publics sont excellents, par touristiques sont les caractéristiques de cette train, bus et bateau. Les grandes villes telles ville. Aujourd'hui, Estavayer-le-lac a environ que Berne, Fribourg, Lausanne peuvent être atteintes par l'autoroute A1 ou en train à 6‘200 habitants. Le taux d'imposition actuel court terme. est 0,84. La ville francophone est le centre régional et économique du part fribourgeois de la Broye. Le 1er janvier 2017, Estavayer-le-lac a fusionné avec les anciennes municipalités Bussy, Morens, Murist, Rueyres-les-Prés, Vernay und Vuissens à la nouvelle communauté politique Estavayer. Infrastructure – à Estavayer vous trouverez tout ce dont vous avez besoin; Garderie, groupes de jeu, jardins d'enfants et les écoles publiques (centre primaire et supérieur), des magasins comme Coop, Migros MM, satellite Denner, les magasins d'alimentation spécialisés pour les besoins quotidiens, boutiques, restaurants, comptoirs postaux et bancaires, tous dans le centre à distance de marche. Parcelle N° 2236 SITUATION Les Esserpis, Estavayer-le-Lac Ecoles Sport Shopping 1. Ecole primaire 4. Centre sportive 7. Migros 2. Ecole publique 5. Studio Yoga 8. -

Semaine 49 Du 29 Novembre Au 6 Décembre

SAMEDI 5 DECEMBRE 2020 — 2ème DIMANCHE DE L’AVENT Du 28 novembre au 6 décembre 2020– Année B Collégiale 17h30 † Jean Ballaman et sa fille Nicole Crausaz † Lana, Noemie, Sem. 49 (civile) – I (liturgique) Pierre Dénervaud, Yaw, Emanuel, Faustina Boateng, Olivier, Jean-Marc Scherrer, Jean Marshal Paroisse Saint-Laurent Estavayer Forel 18h30 † Marie, Ernest Sansonnens et déf. fam. † (f.) Lucien et Agnès Duc † (f.) Elyse Marmy DIMANCHE 6 DECEMBRE 2020 — 2ème DIMANCHE DE L’AVENT Collégiale 09h00 Messe radiodiffusée † Agathe, Henri et Jacques Wittmer † Jean et Louise Monnerat † Marie-Thérèse et Emile Noble-Pury † Mimi Schmid † Marie-Thérèse et Joseph Vonlanthen † (f.) André Martin † (f.) Emile et Maria Chassot Il n’y aura pas de Noël cette année ? Bien sûr qu’il y en aura un ! Cheyres 10h00 Messe Patronale Plus silencieux et plus profond, plus semblable au premier Noël quand Jésus est né. Sans beaucoup † Bernard Nidegger et déf. fam., René Weiss † Francine de lumière sur la terre et pas d’impressionnantes parades royales, mais avec l’humilité des bergers Delley, Oscar, Marinette, Victor et Marie-Louise Pillonel et à la recherche de la Vérité. Sans grands banquets, mais avec la présence d’un Dieu tout puissant. par. déf. † Jeannette Mollard † Louis et Claude Pillonel Il n’y aura pas de Noël cette année ? † Pascal Tinguely † Bernard Pillonel et parents déf.. Bien sûr qu’il y en aura un ! † André Girard et parents déf † Jeannette Mollard Sans que les rues ne débordent, mais avec un cœur ardent pour Celui qui est sur le point d’arriver. † (f.) Georges et Alice Noble † (f.) Ida Dévaud Pas de bruit ni de tintamarres, ni de réclamations et de bousculades… Mais en vivant le Mystère, † (f.) Joseph et Catherine Bulliard sans peur du « covid-Hérode », lui qui prétend nous enlever le rêve de l’attente. -

Le Pigeon Aux Œufs D'or

| ACTUALITÉ Jeudi 7 janvier 2021 7 Le PLR, premier à Le pigeon aux œufs d’or dévoiler ses candidats ÉLECTIONS COMMUNALES Russo. Une rumeur enflait qui ÉLEVAGE Au niveau mondial, les courses de pigeons voyageurs suscitent l’engouement avec Le PLR staviacois publie la voyait s’inscrire sur cette liste le des transferts d’athlètes dignes de stars du football. Rencontre avec un éleveur passionné. liste de ses candidats. Les nom de l’ancien syndic d’Esta- autres partis maintiennent vayer-le-Lac Albert Bachmann. Il le suspense. n’y figure pas mais reconnaît qu’il MONTBRELLOZ mélanges très complexes et d’eau a été approché par deux partis acidifiée pour éviter le dévelop- ESTAVAYER sans pour l’instant prendre au- in d’après-midi dans la pement de bactéries et sont étroi- cune décision. Broye. Au terme de leur vol tement contrôlés par des vétéri- Ils sont les premiers à sortir offi- Dans les autres rangs, on se Fdu jour, une nuée de pi- naires. Le dopage (cortisone, ca- ciellement du bois. Le Parti libé- tâte encore. PDC Estavayer, socia- geons regagne sa maison à l’entrée féine) existe dans ce sport. Parce ral-radical (PLR) d’Estavayer a dé- listes (PS), UDC et Indépendants de Montbrelloz. Le grand colom- que ces compétitions, au niveau posé sous le sapin de Noël des ha- peaufinent leurs listes. Nouveaux bier aux allures de mobile-home international, c’est du sérieux bitants de la commune, via une venus, les Verts, qui viennent de enregistre les heures d’arrivée des pour arriver à des transferts dé- annonce publicitaire, sa liste de fonder une section broyarde, as- oiseaux grâce à un système de lec- passant le million. -

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland

A New Challenge for Spatial Planning: Light Pollution in Switzerland Dr. Liliana Schönberger Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Light pollution ............................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1 The origins of artificial light ................................................................................ 4 1.1.2 Can light be “pollution”? ...................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Impacts of light pollution on nature and human health .................................... 6 1.1.4 The efforts to minimize light pollution ............................................................... 7 1.2 Hypotheses .................................................................................................................. 8 2 Methods ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Literature review ......................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Spatial analyses ........................................................................................................ 10 3 Results ....................................................................................................................11 -

Pp P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P

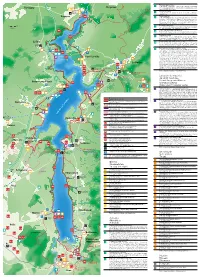

Piscine en plein air, Broc 6 T. +41 (0)26 921 17 36. Ouverte de juin à août (par beau temps) / Schwimmbad Farvagny 5 Rossens Treyvaux von Juni bis August geöffnet (bei schönem Wetter) / Outdoor pool open from 1 1 25’ June to August (by nice weather). Parcours vita, Bulle Rossens 2 P 7 Parcours de 2.3 km / Vita Parcours, Strecke von 2.3 km / Vita assault course, Village P route of 2.3 km. Rossens Permis de pêche 45’ 8 T. +41(0)848 424 424. Permis de pêche délivrés par la Préfecture et les offices Barrage du Lac 20’ du tourisme de Bulle, Gruyères et Charmey / Fischereipaten werden durch de La Gruyère 55’ das Oberamt des Bezirks und die Tourismusbüros von Bulle, Gruyères und 25’ Charmey ausgestellt / Fishing licences are issued by the district’s prefecture and tourism offices in Bulle, Gruyères and Charmey. 0500 m RandoLama, Echarlens 9 T. +41 (0)79 362 14 86. Balade avec des lamas, sur réservation / Wanderung 1 : 25’000 mit Lamas, auf Voranmeldung / Llama hikes, by reservation. Centre équestre de Marsens, Marsens 10 Falaise à T. +41 (0)26 915 04 60. Cours, stages, sur réservation / Reiterhof: Kurse, Lager, tête d’éléphant 50’ auf Voranmeldung / Riding stables: Lessons, workshops. By reservation. EasyBallon, Sorens 11 T. +41 (0)79 651 81 19. Vols en montgolfière au-dessus du Lac de La Gruyère, sur réservation / Heissluftballonfahrt über dem «Lac de La Gruyère», auf Vor- anmeldung / Hot air balloon flights over the lake «Lac de La Gruyère». Le Bry Fondue & Wine Bar sur l’Ile d’Ogoz, Le Bry 12 T. -

Statistique Fiscale Steuerstatistik

Statistique fi scale Steuerstatistik — 2010 — Murten NNeuchâtel Lac de Morat Murtensee Impôt cantonal sur le revenu et la fortune des personnes physiques Kantonssteuer auf dem Einkommen und Vermögen der natürlichen Personen Impôt cantonal sur le bénéfi ce et le capital des personnes morales Lac de Kantonssteuer auf dem Gewinn und Kapital der juristischen Personen fenensee Estavayyer- Schif le-Lac Tafers Fribourg Romont ère Gruyèr Schwarzsee la Lac de Bulle Montsalvens Lac de Lac Châtel-St-Denis — Direction des fi nances DFIN Finanzdirektion FIND Table des matières Inhaltsverzeichnis — — Avant-propos 3 Vorwort 3 Statistique du rendement de l’impôt cantonal Statistik des Ertrags der einfachen Kantonssteuer de base 2010 des personnes physiques 4 2010 der natürlichen Personen 4 Par district 4 Nach Bezirken 4 Par commune / par habitant 6 Nach Gemeinden / nach Einwohner 6 Carte cantonale 9 Karte des Kantons 9 Impôt sur le revenu 10 Einkommenssteuer 10 Composition du revenu imposable 12 Zusammensetzung des steuerbaren Einkommens 12 Impôt sur la fortune 13 Vermögenssteuer 13 Composition de la fortune imposable 15 Zusammensetzung des steuerbaren Vermögens 15 Evolution 16 Entwicklung 16 Statistique du rendement de l’impôt cantonal Statistik des Ertrags der einfachen Kantonssteuer de base 2010 des personnes morales 19 2010 der juristischen Personen 19 Par district 20 Nach Bezirken 20 Par commune 20 Nach Gemeinden 20 Par catégorie 21 Nach Kategorien 21 Evolution 22 Entwicklung 22 Données statistiques de l’impôt cantonal de base Statistische Daten der -

ENTSCHEIDUNG DER KOMMISSION Vom 25. März 1997 Zur Aufstellung

1997D0252 — DE — 09.03.2001 — 009.001 — 1 Dieses Dokument ist lediglich eine Dokumentationsquelle, für deren Richtigkeit die Organe der Gemeinschaften keine Gewähr übernehmen " B ENTSCHEIDUNG DER KOMMISSION vom 25. März 1997 zur Aufstellung der vorläufigen Listen der Drittlandsbetriebe, aus denen die Mitgliedstaaten die Einfuhr zum Verzehr bestimmter Milch und Erzeugnisse auf Milchbasis zulassen (Text von Bedeutung für den EWR) (97/252/EG) (ABl. L 101 vom 18.4.1997, S. 46) Geändert durch: Amtsblatt Nr. Seite Datum "M1 Entscheidung 97/480/EG der Kommission vom 1. Juli 1997 L 207 1 1.8.1997 "M2 Entscheidung 97/598/EG der Kommission vom 25. Juli 1997 L 240 8 2.9.1997 "M3 Entscheidung 97/617/EG der Kommission vom 29. Juli 1997 L 250 15 13.9.1997 "M4 Entscheidung 97/666/EG der Kommission vom 17. September L 283 1 15.10.1997 1997 "M5 Entscheidung 98/71/EG der Kommission vom 7. Januar 1998 L 11 39 17.1.1998 "M6 Entscheidung 98/87/EG der Kommission vom 15. Januar 1998 L 17 28 22.1.1998 "M7 Entscheidung 98/88/EG der Kommission vom 15. Januar 1998 L 17 31 22.1.1998 "M8 Entscheidung 98/89/EG der Kommission vom 16. Januar 1998 L 17 33 22.1.1998 "M9 Entscheidung 98/394/EG der Kommission vom 29. Mai 1998 L 176 28 20.6.1998 "M10 Entscheidung 1999/52/EG der Kommission vom 8. Januar 1999 L 17 51 22.1.1999 "M11 Entscheidung 2001/177/EG der Kommission vom 15. Februar L 68 1 9.3.2001 2001 1997D0252 — DE — 09.03.2001 — 009.001 — 2 !B ENTSCHEIDUNG DER KOMMISSION vom 25. -

Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings

Swiss Family Hotels & Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings 2019. Lodgings. MySwitzerland.com Presented by Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings at a glance. Switzerland is a small country with great variety; its Swiss Family Hotels & Lodgings are just as diverse. This map shows their locations at a glance. D Schaffhausen B o d e n A Aargau s Rhein Thur e e Töss Frauenfeld B B Basel Region Limm at Liestal Baden C irs Bern B Aarau 39 St-Ursanne Delémont Herisau Urnäsch D F A Appenzell in Fribourg Region Re 48 e 38 h u R ss Säntis Z 37 H ü 2502 r i c Wildhaus s Solothurn 68 E ub h - s e e Geneva o 49 D e L Zug Z 2306 u g Churfirsten Aare e Vaduz r W s a e La Chaux- 1607 e lense F e L 47 Lake Geneva Region Chasseral i de-Fonds e 44 n Malbun e s 1899 t r h e 1798 el Grosser Mythen Bi Weggis Rigi Glarus G Graubünden Vierwald- Glärnisch 1408 42 Schwyz 2914 Bad Ragaz Napf 2119 Pizol Neuchâtel are stättersee Stoos A Pilatus 43 Braunwald 46 2844 l L te Stans an H hâ d Jura & Three-Lakes c qu u Sarnen 1898 Altdorf Linthal art Klosters Ne Stanserhorn R C Chur 2834 24 25 26 de e Flims ac u Weissfluh Piz Buin L 2350 s 27 Davos 3312 32 I E 7 Engelberg s Tödi 23 Lucerne-Lake Lucerne Region mm Brienzer 17 18 15 e Rothorn 3614 Laax 19 20 21 Scuol e 40 y 45 Breil/Brigels 34 35 Arosa ro Fribourg Thun Brienz Titlis Inn Yverdon B 41 3238 a L D rs. -

Bernese Anabaptist History: a Short Chronological Outline (Jura Infos in Blue!)

Bernese Anabaptist History: a short chronological outline (Jura infos in blue!) 1525ff Throughout Europe: Emergence of various Anabaptist groups from a radical reformation context. Gradual diversification and development in different directions: Swiss Brethren (Switzerland, Germany, France, Austria), Hutterites (Moravia), Mennonites [Doopsgezinde] (Netherlands, Northern Germany), etc. First appearance of Anabaptists in Bern soon after 1525. Anabaptists emphasized increasingly: Freedom of choice concerning beliefs and church membership: Rejection of infant baptism, and practice of “believers baptism” (baptism upon confession of faith) Founding of congregations independent of civil authority Refusal to swear oaths and to do military service “Fruits of repentance”—visible evidence of beliefs 1528 Coinciding with the establishment of the Reformation in Bern, a systematic persecution of Anabaptists begins, which leads to their flight and migration into rural areas. Immediate execution ordered for re-baptized Anabaptists who will not recant (Jan. 1528). 1529 First executions in Bern (Hans Seckler and Hans Treyer from Lausen [Basel] and Heini Seiler from Aarau) 1530 First execution of a native Bernese Anabaptist: Konrad Eichacher of Steffisburg. 1531 After a first official 3-day Disputation in Bern with reformed theologians, well-known and successful Anabaptist minister Hans Pfistermeyer recants. New mandate moderates punishment to banishment rather than immediate execution. An expelled person who returns faces first dunking, and if returning a second time, death by drowning . 1532 Anabaptist and Reformed theologians meet for several days in Zofingen: Second Disputation. Both sides declare a victory. 1533 Further temporary moderation of anti-Anabaptist measures: Anabaptists who keep quiet are tolerated, and even if they do not, they no longer face banishment, dunking or execution, but are imprisoned for life at their own expense. -

The Land of the Tüftler – Precision Craftsmanship Through the Ages

MAGAZINE ON BUSINESS, SCIENCE AND LIVING www.berninvest.be.ch Edition 1/2020 IN THE CANTON OF BERN, SWITZERLAND PORTRAIT OF A CEO Andrea de Luca HIDDEN CHAMPION Temmentec AG START-UP Four new, ambitious companies The Land of the Tüftler – introduce themselves Precision Craftsmanship LIVING / CULTURE / TOURISM Espace découverte Énergie – the art Through the Ages of smart in using nature’s strengths Get clarity The Federal Act on Tax Reform and AHV Financing (TRAF) has transformed the Swiss tax landscape. The changes are relevant not only for companies that previously enjoyed cantonal tax status, but all taxpayers in general. That’s why it’s so important to clarify the impact of the reform on an individual basis and examine applicability of the new measures. Our tax experts are ready to answer your questions. kpmg.ch Frank Roth Head Tax Services Berne +41 58 249 58 92 [email protected] © 2020 KPMG AG is a Swiss corporation. All rights reserved. corporation. is a Swiss AG © 2020 KPMG klarheit_schaffen_inserat_229x324_0320_en_v3.indd 1 19.03.20 16:08 Content COVER STORY 4–7 The Land of the Tüftler – Get clarity Precision Craftsmanship Through the Ages START-UP 8/9 Cleveron legal-i The Federal Act on Tax Reform and AHV Financing (TRAF) has Moskito Watch transformed the Swiss tax landscape. The changes are relevant not Dokoki only for companies that previously enjoyed cantonal tax status, but all taxpayers in general. PORTRAIT OF A CEO 10/11 Andrea de Luca That’s why it’s so important to clarify the impact of the reform on HIDDEN CHAMPION 12/13 an individual basis and examine applicability of the new measures. -

Rapport Annuel 2018 1

EauSud SA, société gérée par Gruyère Energie SA Rue de l’Etang 20 | CP 651 | CH-1630 Bulle 1 | T 026 919 23 23 | F 026 919 23 25 [email protected] | www.gruyere-energie.ch | [email protected] | www.eausud.ch RAPPORT ANNUEL 2018 1 1. Entreprise 2 • Brève présentation 4 • Prestations 6 • Assemblée des actionnaires 8 • Actionnariat 9 • Organisation 10 • Chiffres-clés 2018 12 • Carte du réseau d’eau 13 2. Infrastructures 14 3. Exploitation 18 4. Partie financière 22 • Comptes 2018 24 • Rapport de l’organe de révision 30 2 3 ENTREPRISE 1 4 5 AIRE DE DESSERTE (alimentation totale ou partielle) BRÈVE PRÉSENTATION 1. Attalens 2. Bossonnens 3. Botterens 23 4. Broc 5. Bulle 6. Val-de-Charmey (Cerniat) 18 7. Chapelle Créée en 2005, EauSud est une société active dans le captage 8. Châtel-sur-Montsalvens 9. Corbières et l’adduction d’eau en mains de communes ou d’associa- 26 17 10. Crésuz 9 22 11 11. Echarlens tions de communes du sud fribourgeois. 19 25 28 12. Ecublens 30 13. Granges Le but de la société consiste à gérer les captages de Charmey 29 20 3 10 14. Gruyères 5 8 6 15. La Verrerie et de Grandvillard ainsi que les adductions qui y sont liées. 12 24 16. Le Flon 16 Grossiste dans la distribution d’eau, elle approvisionne 15 4 17. Marsens 18. Mézières 30 communes du sud du canton. 7 27 19. Montet 20. Morlon 21 21. Oron (VD) Au vu du développement actuel et à venir des communes 22. -

Contribution À L'étude Des Cluses Du Jura Septentrional

Université de Neuchâtel Institut de géologie Contribution à l'étude des cluses du Jura septentrional Thèse présentée à (a Faculté des sciences de l'Université de Neuchâtel par Michel Monbaron Licencié es sciences Avril 1975 Imprimerie Genodruck, Bienne IMPRIMATUR POUR LA THESE Contribution al Jura septentrional deMQns.i.eur....Mii:hel...JïlDZLhar.Qn. UNIVERSITÉ DE NEUCHATEL FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES La Faculté des sciences de l'Université de Neuchâtel, sur le rapport des membres du jury, .Ml*...ae.s....px.QÍfis.s.eur.s....D*..Jiub.ert.+...P>...XMu.Y£.„„ _(BêSan£QrJ^_J_c£ autorise l'impression de la présente thèse sans exprimer d'opinion sur les propositions qui y sont contenues. Neuchâtel, le 9.~ms,xs....l9l6. Le doyen : P. Huguenin Thèse publiée avec l'appui de : l'Etat de Neuchâtel et l'Etat de Berne. Ce travail a obtenu Le Prix des Thèses 1976 de la Société Jurassienne d'Emulation. IV RESUME Une cluse jurassienne caractéristique, celle du Pichoux, est étudiée sous divers aspects. La localisation de la cluse dans l'anticlinal de Raimeux dépend en premier lieu d'un ensellement- d'axe au toit de l'imperméable oxfordien, ainsi que d'un relais axial dans le coeur de Dogger. Les systèmes de fissuration, principalement les deux sys tèmes cisaillants dextre et sénestre, ont fourni la trame sur laquel le s'est imprimée la cluse. Hydrogéologiquement, celle-ci fait office de niveau de base karstique pour de vastes territoires situés surtout à l'W ("bordure orientale des Franches-Montagnes). La principale sour ce karstique qui y jaillit est celle de Blanches Fontaines: surface du bassin 48,8 km^; débit moyen annuel 1,25 m3/sec; valeur moyenne de l'ablation karstique totale: 0,082 mm/an.