Warabandi in Pakistan's Canal Irrigation Systems Widening Gap Between Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

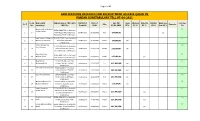

Applications Received for Recruitment As Naib Qasid in Punjab Constabulary Till 07-04-2021

Page 1 of 85 APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR RECRUITMENT AS NAIB QASID IN PUNJAB CONSTABULARY TILL 07-04-2021 Form Name with Address as per CNIC with District of Date of Age Till Open Women Minority Disable Employee Overage/ Sr. # Edu: Remarks No. parentage CNIC No. Domicile Birth 07-04-2021 57% 15 % 05 % 03 % Son 20 % Fit Muhammad Tallat Bhatti Fit 35404-5665873-5 r/o Muhallah s/o Amanullah 1 3 Makki Nagar Mureedkey road Sheikhupura 01/08/2002 FSC 18Y,8M,6D yes Farooqabad Distt: sheikhupura Syed Usman Ali Shah s/o 35404-8415306-5 r/o Chak Wahi Fit 2 4 Mazhar Hussain Shah No.522 PO same Distt: Sheikhupura 01/04/2003 Matric 18Y,0M,6D yes sheikhupura Nabeel Shakoor s/o Fit 35404-8509339-3 r/o Muhallah Abdul Shakoor 3 10 Christian Basti near Church Sheikhupura 07/02/1998 Middle 23Y,2M,0D yes Farooqabad Distt: Sheikhupura Akash Masih s/o Fit 35404-0663146-5 r/o Esa Nagri 4 20 Mukhtar Masih sheikhupura 05/12/1999 Middle 21Y,4M,2D yes road Chhapa road Sheikhupura Majid Ali s/o 35404-3285488-7 r/o Tibbi Fit 5 25 Muhammad Arif Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 27/07/1999 F.A 21Y,8M,11D yes Sheikhupura Saif Ullah s/o Shoukat Ali 35404-4346815-9 r/o timbi Fit 6 26 Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 14/01/1998 F.A 23Y,2M,24D yes Sheikhupura Ehsan Ali s/o Nathha 35404-8753848-1 r/o Tibbi Fit 7 27 Humbo Chak No.578 Distt: sheikhupura 12/10/1996 B.A 24Y,5M,26D yes Sheikhupura Muhammad Faisal s/o 35404-1572400-7 r/o Bhandor Fit 8 28 Muhammad Aslam PO same Farooqaba Distt: sheikhupura 07/01/1999 Matric 22Y,3M,0D yes Sheikhupura Sunny Ameen s/o 35404-8494036-9 -

WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT

IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT 2 | MEDHA BISHT Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-17-8 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Monograph are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. First Published: April 2013 Price: Rs. 280/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Layout & Cover by: Vaijayanti Patankar & Geeta Printed at: M/S A. M. Offsetters A-57, Sector-10, Noida-201 301 (U.P.) Mob: 09810888667 E-mail: [email protected] WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 6 PART I Chapter One ................................................................. -

State Capacity in Punjab's Local Governments

Final report State capacity in Punjab’s local governments Benchmarking existing deficits Gharad Bryan Ali Cheema Ameera Jamal Adnan Khan Asad Liaqat Gerard Padro i Miquel June 2019 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: S-37433-PAK-2 STATE CAPACITY IN PUNJAB’S LOCAL GOVERNMENTS: BENCHMARKING EXISTING DEFICITS Gharad Bryan, Ali Cheema, Ameera Jamal, Adnan Khan, Asad Liaqat Gerard Padro i Miquel This Version: August 2019 Abstract As the developing world urbanizes, there is increasing pressure to provide local public goods and local governments are expected to play an important role in their provision. However, there is little work on the nature of of capacity deficits faced by local governments and whether these deficits are acting as a constraint on performance. We use financial accounts data from Punjab’s local governments for 2018-19 to measure their ability to utilize budgets and find that there is considerable variation in this metric across local governments. We supplement this with a management survey with the top managers whose decisions affect budget utilization in a random sample of 129 out of 193 urban local governments in Punjab. We find that the capacity deficits in local governments are particularly challenging in terms of human resource capabilities, the adoption of automated systems, and legal and enforcement capacity. We also find that better human resource capabilities and the use of managerial incentives are positively correlated with budget utilization. Our evidence provides new insights on the importance of management and human resource capabilities and systems capacity in local governments in a developing country setting. -

Society1 in Lower Chenab Colony: a Case Study of Toba Tek Singh (1900-1947)

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 55, Issue No. 2 (July - December, 2018) Nayyer Abbas * Tahir Mahmood ** Fatima Riffat*** Constructing ‘hydraulic’ Society1 in Lower Chenab Colony: A Case Study of Toba Tek Singh (1900-1947) Abstract This paper focuses on agricultural colonization projects from 1885 to 1947 in Punjab. It will be helpful to understand agricultural colonization of the Punjab by the British government and further to establish a link with migration trends during the partition of Punjab in 1947. Among other canal colonies areas, Lower Chenab Colony greatly transformed the agricultural economy of the Punjab. The case study research material has been primarily drawn from the District Colony Record Office Toba Tek Singh, Punjab Archives Lahore and the British Library. It shows that social engineering through which British government developed Toba Tek Singh, constructed a hydraulic society, controlled by the colonial state through the control of canal waters. Its specific composition also gives clue to the migration trends during the Partition of Punjab in 1947. The local non-Muslims’ (Hindu and Sikh) previous family links with the East Punjab became one of the major factors in their migration to India. Key Words: Hydraulic society, Toba Tek Singh, Social engineering, migration, Lower Chenab colony Introduction History of the canal colonies in the Punjab during colonial period had been researched by the number of historians from different aspects of this project. David Gilmartin analyzed the Punjabi migration to the Canal Colonies during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and provided a critical link ‘between village organization and sate power that lay at the heart of colonial rule’.2 D. -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

37231-033: New Khanki Barrage Construction Project Environmental

Environmental Monitoring Report Bi-Annual Report July-December 2016 PAK: New Khanki Barrage Construction Project Prepared by the Project Management Office (PMO) for Punjab Irrigation Department, Lahore Pakistan and Asian Development Bank This environmental monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. New Khanki Barrage Construction Project (NKBP) PMO Barrages Project Number: 2841-PAK (SF): Islamic Republic of Pakistan: New Khanki Barrage Construction Project (NKBP) Financed by: Asian Development Bank and Government of the Punjab JULY – DECEMBER 2016 Prepared by: Ansar Abbas Senior Environmentalist SMEC/EGC Engr. Anwar Hussain Mujahid, Environmental Specialist SMEC International/ EGC, For: Project Management Office, Irrigation Department, and Government of the Punjab Reviewed by: Malik Pervaiz Arif, Acting Director, Environment & Social PMO Barrages, Canal Bank, Mustafabad, Lahore SMEC International in association with - A - Biannual Environmental M/s EGC, M/s Barqaab and Monitoring Report M/s Atkins International (July-December 2016) New Khanki Barrage Construction Project (NKBP) PMO Barrages -

Village List of Gujranwala , Pakistan

Census 51·No. 30B (I) M.lnt.6-18 300 CENSUS OF PAKISTAN, 1951 VILLAGE LIST I PUNJAB Lahore Divisiona .,.(...t..G.ElCY- OF THE PROVINCIAL TEN DENT CENSUS, JUr.8 1952 ,NO BAHAY'(ALPUR Prleo Ps. 6·8-0 FOREWORD This Village List has been pr,epared from the material collected in con" nection with the Census of Pakistan, 1951. The object of the List is to present useful information about our villages. It was considered that in a predominantly rural country like Pakistan, reliable village statistics should be avaflable and it is hoped that the Village List will form the basis for the continued collection of such statistics. A summary table of the totals for each tehsil showing its area to the nearest square mile. and Its population and the number of houses to the nearest hundred is given on page I together with the page number on which each tehsil begins. The general village table, which has been compiled district-wise and arranged tehsil-wise, appears on page 3 et seq. Within each tehsil the Revenue Kanungo holqos are shown according to their order in the census records. The Village in which the Revenue Kanungo usually resides is printed in bold type at the beginning of each Kanungo holqa and the remaining Villages comprising the ha/qas, are shown thereunder in the order of their revenue hadbast numbers, which are given in column o. Rokhs (tree plantations) and other similar areas even where they are allotted separate revenue hadbast numbers have not been shown as they were not reported in the Charge and Household summaries. -

System of Cities Copy

Punjab Spatial Strat e gy 2017-2047 System of Cities The System of Cities Model describes the interaction between different tiered cities and their functions within a larger urban network. The model helps address the primary spatial (planning) issues faced by Punjab. The current arrangement of large cities in the province suggests that there is an imbalance of resources in Punjab, which further aggra- vates social and economic disparities in the province. The system of cities, as shown below, will only work if all tiers of cities have adequate connectivity, human resource, capital, and infrastructure to perform out their respective functions in the larger system. Lack of understanding of the system of cities in case of Punjab, has enabled ad-hoc planning practices in region. Absence of data, ineffi- cient policy implementation, lack of transparency, and low level of citizen participation has encouraged an environment of ‘quick fixes’ that leads to long term damage and consequently higher debt. Export Manufacturing Import Agriculture Services 1 CityClusters in Punjab The city clustering methodology comprises identifying economically integrated settlements and cities. The clustering concept focuses designating a ‘Hub’ city surrounded by other settlements. The idea is to stop thinking of cities only in terms of their overall size but rather on the overall population of a cluster of cities; with the hub providing all necessary services for the region. Hazro Murree Kotli ! Attock ! Taxila Sattian ! ! ! Fateh Rawalpindi ! Jhang ! Kahuta Jand -

City Location Type Address Abbotabad ABBOTABAD BRANCH

City Location Type Address Abbotabad ABBOTABAD BRANCH ATM Shop # 841,Farooqabad Mansehra Road,Abbottabad Ahmed Pur Ahmed Pur Easr ATM 22, Dera Nawab Road, Adjacent Civil Hospital, Ahmed Pur, Arifwala ARIFWALA BRANCH ATM 173-D Thana Bazar Arifwala.Multan Attock Attock ATM Faysal Bank Limited Plot # 169 Shaikh jaffar plaza Saddiqui road Attock city Azad Kashmir Mir Akbar Plaza AK ATM Akbar Plaza, Plot No.2, Sector A/2, Mirpur, Azad Kashmir Bahawalnagar Bahawalnagar ATM Shop # 02 Ghalla Mandi ,Bahawalnagar Bahawalpur NOOR MAHALROAD BR.H ATM 2 - Rehman Society, Noor Mahal Road, Bahawalpur IBB Circular Road Bahawalpur ATM IBB Circular Road Bahawalpur Bahawalpur Yazman Mandi ATM 56/A-DB Bahawalpur Road Bannu Bannu ATM Khasra No. 1462/1833, Mouza Fatima Khel, Near Durrani Plaza, Ex GTS Chowk, Bannu Cantt., Bannu. Bhalwal BHALWAL-1 ATM Liaqat Shaheed Road Tehsil Bhalwal Distt Surghodha Bhalwal branch Burewala BUREWALA BRANCH ATM 95-C, Multan Road, Burewala chakwal Chakwal ATM FBL-Talha gang road, opposite Alliace travel, chakwal. Charsadda Islamic Branch - Charsadda ATM Ground Floor, Gold Mines Towers, Noweshera Road, Charsadda Cheechawatni CHEECHAWATNI BRANCH ATM G.T Road Chichawatni Cheshtian Cheshtian ATM 143 B - Block Main Bazar Cheshtian D.I. Khan IBB D.I.Khan ATM No.19, Survey No.79, Near GPO Chowk, East Circular Road, D.I. Khan Cantt. Depalpur DEPALPUR RD. OKARA ATM Shop # 1& 2,Khewat # 1822,Khatooni 2930 To 2940,Gillani Heights,Madina Chowk Dera Ghazi Khan DGK-JAMPUR ROAD ATM Pakistan Plaza, Jampur Road, Dera Ghazi Khan. Dudial Dudial ATM Hussain Shopping Centre, Main Bazar Branch, Dudial, Azad Kashmir. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Sheikhupura Audit Year

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT SHEIKHUPURA AUDIT YEAR 2016-17 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENT ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ............................................................ i PREFACE .................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................... iv Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ............................................................. vii Table 2: Audit Observations Classified by Categories .......................... vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ................................................................. viii Table 4: Irregularities Pointed Out ........................................................ ix Table 5: Cost Benefit ............................................................................ ix CHAPTER-1 ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 District Government, Sheikhupura ................................................... 1 1.1.1 Introduction of Departments ............................................................. 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ................. 1 1.1.3 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance with PAC/ZAC Directives ......................................................................................... 4 1.2 AUDIT PARAS ............................................................................. 5 1.2.1 Mis-appropriation............................................................................ -

Sheikhupura Eligible

Page 1 of 4 APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR RECRUITMENT AS KHALASI IN PUNJAB CONSTABULARY TILL 07-04-2021 FROM DISTRICT SHEIKHUPURA ELIGIBLE Form Address as per CNIC District of Date of Age Till Open Women Minority Disable Employee Overage/ Sr. # Name with parentage Edu: Remarks No. with CNIC No. Domicile Birth 07-04-2021 57% 15 % 05 % 03 % Son 20 % Fit 35404-4825478-9 Fayyaz Ahmed s/o Villlage Mustafa Abad PO 1 59 Sheikhupura 04/08/1999 Matric 21Y,8M,3D yes Fit Maqsood Alam Ajnianwala Tehsil & District Sheikhupura 35404-0305829-5 Near Police Colony Muhammad Arslan s/o 2 326 Mohallah Qadir Abad Sheikhupura 01/05/1994 F.A 26Y,11M,6D yes Fit Shoukat Ali Farooqabad Tehsil & District Sheikhupura 35404-9616429-9 Mohallah Rasool Pura Shakil Ahmed s/o 3 337 Ward No.4, Sharqi, Sheikhupura 26/03/1998 Matric 23Y,0M,12D Yes Fit Muhammad Boota Farooqabad Tehsil & District Sheikhupura 35404-0393900-5 Mohallah Rehman Irfan Nazir Masih s/o 4 436 pura Old Nokhar Sheikhupura 05/04/1992 Matric 29Y,0M,2D yes Fit Nazir Masih Farooqabad Tehsil & District Sheikhupura 35404-2359914-3 Muhammad Faisal Jandiala Sher Khan PO 5 1277 Afzal s/o Muhammad Sheikhupura 03/05/1998 DAE 22Y,11M,4D yes Fit Khas Tehsil & District Afzal Sheikhupura 35404-7191412-3 Sufyan Younis s/o Gujjiana Nao, PO Khas 6 1363 Sheikhupura 31/12/1998 Middle 22Y,3M,7D yes Fit Muhammad Younis Tehsil & District Sheikhupura Page 2 of 4 Form Address as per CNIC District of Date of Age Till Open Women Minority Disable Employee Overage/ Sr. -

Seniority List 05-11-2020

OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE (Legal), POLICE TRAINING SCHOOL, FAROOQABAD Phone No.056-3876118 k- Fax No.056-3875118 To MR. TAIMOOR EHSAN, Section Officer (CP-VII), Government of Pakistan, Cabinet Secretariat, Establishment Division, Islamabad. No. 2_ti 6 /PTS, Dated 02.11.2020 CIRCULAR Subject: pROVISIONAL SENIORITY LIST OF BS-18 OFFICERS OF THE POLICE SERVICE OF PAKISTAN OFFICERS Memorandum: Kindly refer to your good-office circular issued vide No.2/11/2009/CP-VII, dated 20.10.2020 on captioned subject. It is mentioned here that my name exists at serial number 173 with P-No.1789 but my date of birth has been mentioned wrongly as 27.01.1961(whereas my actual date of birth as per record is 27.07.1961). Even the correct date of birth was mentioned in the list maintained by your office as on 15.01.2020 (copy attached). In view of the above stated facts/submissions, necessary corrections be made in your office record, please. v . 14-Ort 02 —11 262P (RANA MUHAMMAO ANWAR KHAN)PSP Superintendent of Police (Legal) Police Training School Farooqabad, District Sheikhupura. Copy of the above is forwarded for kind information to the:- 1. A.D/R.0(PD-I), Establishment Division, Islamabad. Lit!' Direct (IT), Establishment Division, Islamabad. Year 2020/SP/Leval/Letter 1020 GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT ESTABLISRMENT DIVISION No. 2/11/2009/CP-VII Islatnabad the 20th October, 2020 CIRCULAR Subject: - PROVISIONAL SENIORITY LIST OF BS-18 OFFICERS OF THE POLICE SERVICE OF PAKISTAN OFFICERS. Provisional Seniority List of BS-18 officers of Police Service of Paistait as on I 16.09.2020 is enclosed herewith for information of all concerned—Objections, ifI uny,I I may be communicated within one month of its issuance.