Society1 in Lower Chenab Colony: a Case Study of Toba Tek Singh (1900-1947)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abundance and Fluctuation in Spider Diversity in Citrus Fruits from Located in Vicinity of Faisalabad Pakistan

June 2016 Vol. 23 No. 2 59-64 ScienceDirect Journal of Northeast Agricultural University (English Edition) Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Abundance and Fluctuation in Spider Diversity in Citrus Fruits from Located in Vicinity of Faisalabad Pakistan Maqsood I1, Mohsin S B1, Li Yi-jing1, Tang Li-jie1, Saleem K M2, Khalil U R3, Shahla A3, Aoun Bukhari4, and S S Jamal5 1 College of Veterinary Medicine, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China 2 Department of Wild Life and Fisheries, Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan 3 College of Resources and Environment, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China 4 Department of Entomology, University of Punjab, Pakistan 5 School of Management, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin 150001, China Abstract: Spiders for the present study were collected from different fruit gardens (i.e. citrus) located at various localities (i.e., Tehsil Samundri, Jaranwala, Tandlianwala and Faisalabad) of District Faisalabad, Pakistan. Spiders belonging to six families and 33 species were captured from the two fruit gardens during the one year of this study. The citrus fruits garden was found to be best populated habitat as compared to other fruit garden. These sites were sampled by using pitfall traps; each month for five consecutive days from September 2010 to March 2011. As a result, 1 054 specimens were captured representing six families viz: lycosidae, thomosidae, gnaphosidae, saltisidae, araneidae and clubionidae. Lycosidae was more abundant, while clubionidae was less diverse during the study. Maximum population fluctuation among the spider specimens showed during the months from September and October, while the least abundance of spider specimens was reordered during June, November and December. -

FIRMS in AOR of RD PUNJAB Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD

Appendix-A FIRMS IN AOR OF RD PUNJAB Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD 1 M/s A.A Textile Processing Industries, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 2 M/s A.B Exports (Pvt) Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 3 M/s A.M Associates, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 4 M/s A.M Knit Wear, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 5 M/s A.S Chemical, Multan Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 6 M/s A.T Impex, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 7 M/s AA Brothers Chemical Traders, Sialkot Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 8 M/s AA Fabrics, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 9 M/s AA Spinning Mills Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 10 M/s Aala Production Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 11 M/s Aamir Chemical Store, Multan Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 12 M/s Abbas Chemicals, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab M/s Abdul Razaq & Sons Tezab and Spray Centre, 13 Hydrochloric Acid Punjab Toba Tek Singh 14 M/s Abubakar Anees Textiles, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 15 M/s Acro Chemicals, Lahore Toluene & MEK Punjab 16 M/s Agritech Ltd, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 17 M/s Ahmad Chemical Traders, Muridke Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 18 M/s Ahmad Chemmicals, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 19 M/s Ahmad Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Khanewal Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 20 M/s Ahmed Chemical Traders, Faisalabad Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 21 M/s AHN Steel, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 22 M/s Ajmal Industries, Kamoke Hydrochloric Acid Punjab 23 M/s Ajmer Engineering Electric Works, Lahore Hydrochloric Acid Punjab Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 24 M/s Akbari Chemical Company, -

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

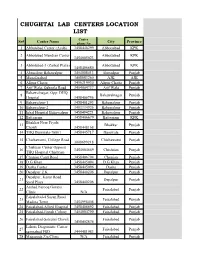

Chughtai Lab Centers Location List

CHUGHTAI LAB CENTERS LOCATION LIST Center Sr# Center Name City Province phone No 1 Abbotabad Center (Ayub) 3458448299 Abbottabad KPK 2 Abbotabad Mandian Center Abbottabad KPK 3454005023 3 Abbotabad-3 (Zarbat Plaza) Abbottabad KPK 3458406680 4 Ahmedpur Bahawalpur 3454008413 Ahmedpur Punjab 5 Muzafarabad 3408883260 AJK AJK 6 Alipur Chatta 3456219930 Alipur Chatta Punjab 7 Arif Wala, Qaboola Road 3454004737 Arif Wala Punjab Bahawalnagar, Opp: DHQ 8 Bahawalnagar Punjab Hospital 3458406756 9 Bahawalpur-1 3458401293 Bahawalpur Punjab 10 Bahawalpur-2 3403334926 Bahawalpur Punjab 11 Iqbal Hospital Bahawalpur 3458494221 Bahawalpur Punjab 12 Battgaram 3458406679 Battgaram KPK Bhakhar Near Piyala 13 Bhakkar Punjab Chowk 3458448168 14 THQ Burewala-76001 3458445717 Burewala Punjab 15 Chichawatni, College Road Chichawatni Punjab 3008699218 Chishtian Center Opposit 16 3454004669 Chishtian Punjab THQ Hospital Chishtian 17 Chunian Cantt Road 3458406794 Chunian Punjab 18 D.G Khan 3458445094 D.G Khan Punjab 19 Daska Center 3458445096 Daska Punjab 20 Depalpur Z.K 3458440206 Depalpur Punjab Depalpur, Kasur Road 21 Depalpur Punjab Syed Plaza 3458440206 Arshad Farooq Goraya 22 Faisalabad Punjab Clinic N/A Faisalabad-4 Susan Road 23 Faisalabad Punjab Madina Town 3454998408 24 Faisalabad-Allied Hospital 3458406692 Faisalabad Punjab 25 Faisalabad-Jinnah Colony 3454004790 Faisalabad Punjab 26 Faisalabad-Saleemi Chowk Faisalabad Punjab 3458402874 Lahore Diagonistic Center 27 Faisalabad Punjab samnabad FSD 3444481983 28 Maqsooda Zia Clinic N/A Faisalabad Punjab Farooqabad, -

Saadat Hasan Manto's “Toba Tek Singh”

SAADAT HASAN MANTO’S “TOBA TEK SINGH” Deepak Assistant Professor (English, MGCUB) Former, Jr. Research Assistant, Penn State University, USA PARTITION Partition, one the saddest moments of India in twentieth century, is a dominant sad theme in Indian literature, either English or in Vernaculars. The sadness can be imagined by the fact that around 10 to 12 million Indians displaced during the event that is followed by butchering, killing, prostitution and even in rapes of women of opposite religion. A host of writers like Amrita Pritam, Khushwant Singh, Salman Rushdie, Bhisham Sahni and others put pen to it. MANTO It was the selection of shocking and real life stories which makes Manto one of the most controversial short-story writer of the time. In his small career of some 20 years, Manto never afraid to expose the madness, nakedness and hollowness of the society around him. His theme somewhere surpasses the Progressive Writers’ Association and other place over take the social-realism. In short, he was more progressive and more realist than any other author of the time. His popular partition stories are (mp3 link from youtube) Titwal Ka Kutta (https://youtu.be/6OGpyfjWkAM) Toba Tek Singh (https://youtu.be/wLfwvQc8R-A) Khol Do (https://youtu.be/GqBp32oXU5I) Thanda Ghost (https://youtu.be/kiLh-DNinwQ) BACKGROUND Manto, the more real than realists or to say socio-realists, tragically showcased the real life stories of the victims exposed to the partition, both from India and Pakistan. Manto’s short story “Toba Tek Singh,” written shortly before his death, is a live example of it that has its setting in the environment surrounded by the Partition of India. -

Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (Ii) the Dog of Tithwal

Black Ice Software LLC Demo version WELCOME MESSAGE Welcome to PG English Semester IV! The basic objective of this course, that is, 415 is to familiarize the learners with literary achievements of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints you with modern movements in Indian thought to appreciate the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. You are advised to consult the books in the library for preparation of Internal Assessment Assignments and preparation for semester end examination. Wish you good luck and success! Prof. Anupama Vohra PG English Coordinator 1 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version 2 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version SYLLABUS M.A. ENGLISH Course Code : ENG 415 Duration of Examination : 3 Hrs Title : Indian Writing in English Total Marks : 100 Translation Theory Examination : 80 Interal Assessment : 20 Objective : The basic objective of this course is to familiarize the students with literary achievement of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints the students with modern movements in Indian thought to compare the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. UNIT - I Premchand Nirmala UNIT - II Saadat Hasan Manto, (i) Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (ii) The Dog of Tithwal (iii) The Price of Freedom UNIT III Amrita Pritam The Revenue Stamp: An Autobiography 3 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version UNIT IV Mohan Rakesh Half way House UNIT V Gulzar (i) Amaltas (ii) Distance (iii)Have You Seen The Soul (iv)Seasons (v) The Heart Seeks Mode of Examination The Paper will be divided into section A, B and C. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Study of Groundwater Recharge in Rechna Doab Using Isotope Techniques

\ PINSTECH/RIAD-133 STUDY OF GROUNDWATER RECHARGE IN RECHNA DOAB USING ISOTOPE TECHNIQUES M. ISHAQ SAJJAD M. AZAM TASNEEM MANZOOR AHMAD S. D. HUSSAIN IQBAL H. KHAN WAHEED AKRAM RADIATION AND ISOTOPE APPLICATIONS DIVISION Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology P. O. Nilore, Islamabad June, 1992 PINSTECH/RIAD-133 STUDY OF GROUNDWATER RECHARGE IN RECHNA DOAB USING ISOTOPE TECHNIQUES M. ISHAQ SAJJAD M. AZAM TASNEEM MANZOOR AHMAD S. D. HUSSAIN IQBAL H. KHAN WAHEED AKRAM RADIATION AND ISOTOPE APPLICATIONS DIVISION PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF NUCLEAR SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY P. 0. NILORE, ISLAMABAD. June, 1992 CONTENTS ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION THE PROJECT AREA 2.1 General Description of The Area 2.2 Climate 2.3 Surface and Subsurface Geology FIELD WORK LABORATORY WORK RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 5.1 Sources of Groundwater Recharge 5.1.1 Isotopic Data of River/Canal System 5.1.1.1 River Chenab 5.1.1.2 River Ravi 5.1.1.3 Upper Chenab Canal (UCC) 5.1.1.4 Lower Chenab Canal (LCC) 5.1.2 Isotopic Data of Rains ISOTOPIC VARIATIONS IN GROUNDWATER 6.1 Some Features of SD-S^O Diagrams 6.2 Spatial and Temporal Variations of Isotopic Data THE GROUNDWATER RECHARGE FROM DIFFERENT INPUT SOURCES TURN-OVER TIMES OF THE GROUNDWATER VERTICAL DISTRIBUTION OF ISOTOPES CONCLUSIONS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS REFERENCES \ ABSTRACT Isotopic studies were performed in the Rechna Doab area to understand the recharge mechanism, investigate the relative contributions from various sources such as rainfall, rivers and canal system and to estimate the turn-over times and replenishment rate of groundwater. The isotopic data suggest that the groundwater in the project area, can be divided into different zones each having its own characteristic isotopic composition. -

A GIS Based Assessment of Heavy Metals Contamination in Surface

aphy & N r at og u e ra G l f D o i Mondal, J Geogr Nat Disast 2012, 2:1 s l a Journal of a s n t DOI: 10.4172/2167-0587.1000105 r e u r s o J ISSN: 2167-0587 Geography & Natural Disasters ResearchResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access A GIS Based Assessment of Heavy Metals Contamination in Surface Soil of Urban Parks: A Case Study of Faisalabad City-Pakistan Parveen N1*, Ghaffar A2, Shirazi SA2 and Bhalli MN3 1Department of Geography, GC University Faisalabad, Pakistan 2Department of Geography, Punjab University Lahore, Pakistan 3Department of Geography, Govt. Postgraduate College Gojra, Pakistan Abstract The study investigated the environmental attribute of urban parks for risk assessment due to heavy metals mobilization into biosphere. Sixteen busiest urban parks located in the city of Faisalabad were analyzed for the Copper, Zinc, Nickel and Lead contamination. The research foundation was derived through the experimental observations. Analytical determinations of heavy metals contents were performed by ICP (Inductively Coupled Plasma) optical emission spectroscopy. Multivariate Geospatial analyses were performed, using GIS (Geographic Information System) techniques and statistical analysis with the help of SPSS 14. The investigations revealed that the metals mean concentration in the study area ranged from 25.02-111.15, 13.83-53.23, 9.30-26.00 and 0.00-18.93 mg/Kg for Zinc, Copper, Nickel and Lead respectively. One of the sites among the selected urban parks was reported to cross the acceptable limits for the Copper contamination in the soil which is pertinent to hepatic and basal ganglia degeneration. -

WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT

IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR in PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 18 April 2013 WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT MEDHA BISHT 2 | MEDHA BISHT Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-17-8 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Monograph are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. First Published: April 2013 Price: Rs. 280/- Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Layout & Cover by: Vaijayanti Patankar & Geeta Printed at: M/S A. M. Offsetters A-57, Sector-10, Noida-201 301 (U.P.) Mob: 09810888667 E-mail: [email protected] WATER SECTOR IN PAKISTAN: POLICY, POLITICS, MANAGEMENT | 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 6 PART I Chapter One ................................................................. -

Site Investigation of Open Dumping Site of Municipal Solid Waste in Faisalabad Hafsa Yasin1* and Muhammad Usman1

Earth Science Pakistan (ESP) 1(1) (2017) 23-25 Contents List available at RAZI Publishing ISSN: 2521-2893 (Print) Earth Science Pakistan (ESP) ISSN: 2521-2907 (Online) Journal Homepage: http://www.razipublishing.com/journals/earth-science- pakistan-esp/ https://doi.org/10.26480/esp.01.2017.23.25 Site investigation of open dumping site of Municipal Solid Waste in Faisalabad Hafsa Yasin1* and Muhammad Usman1 1 Department of Structures and Environmental Engineering, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article history: Inappropriately solid waste handling and disposing are promoting environmental problems in Pakistan. Received 26 October 2016 Deteriorating environmental quality is a serious consequence of open dumping site and is rapidly increasing Accepted 10 December 2016 concern for public. To investigate, the causes Muhammada Wala dumping site was chosen. There is a tremendous Available online 9 January 2017 amount of solid waste generating and dumped without any precautionary measures. Due to development of industries and urban areas the condition is going to be harsh. The aim of this study is the site investigation of the Keywords: dumping site and its consequences on environment. Water samples were collected near the site, analyzed in the laboratory and interviews were taken. Significant high TDS was observed in ground water. Communicable diseases and unhygienic environment were revealed from this research. The main collapses of municipal solid waste MSW, open dumping site, systems are unplanned management of the city, intense climatic conditions, absence of awareness of users and environmental concerns community participation, inadequate resources including machinery and lack of funds.