Right to Health 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

Palestinian Shot Near Rafah Crossing by ASSOCIATED PRESS EL-ARISH, Egypt

Palestinian shot near Rafah Crossing By ASSOCIATED PRESS EL-ARISH, Egypt Talkbacks for this article: 5 A Palestinian official at the Rafah border crossing with Gaza was wounded in shooting Friday that Egyptian security and border officials described as an assassination attempt. Mustafa Saad Jbour, a 25-year-old Palestinian officer on the Rafah checkpoint sustained several bullet wounds to the leg, Capt. Mohammed Badr of the Egyptian Sinai security service said. Badr said that Jbour, who was in hospital in the nearby El-Arish town, came under machine gun fire Friday evening in the Egyptian district, just a few hundreds meters (yards) from the Egypt-Gaza crossing, when masked militants in a speeding car sprayed him with bullets and fled the scene. The shooting came after Jbour had informed Egyptian authorities earlier in the week about uncovering a tunnel in the border city of Rafah, that allegedly was used to smuggle weapons and Palestinians from the Sinai Peninsula into Gaza. Hospital officials at El-Arish said that Jbour has lost a lot of blood and would be transferred to another hospital for surgery. Badr also said that the tunnel discovered by Jbour contained over 30,000 bullets and was located in the middle of a field, about 5 kilometers (3 miles) north of Rafah and within meters (yards) of the boundary. Egypt was coordinating with Palestinian authorities in Gaza to close the newly discovered tunnel from the other end, Badr added. Israel has long accused Egypt of not doing enough to stop the smuggling of weapons to Palestinian militants. -

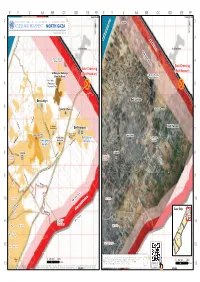

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Nickolay Mladenov Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process Security Council Briefing on the Situation in the Mi

(As Delivered) NICKOLAY MLADENOV SPECIAL COORDINATOR FOR THE MIDDLE EAST PEACE PROCESS SECURITY COUNCIL BRIEFING ON THE SITUATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF UNSCR 2334 (2016) 29 September 2020 Mister President, Members of the Security Council, On behalf of the Secretary-General, I will devote this briefing to presenting his fourteenth report on the implementation of Security Council resolution 2334, covering the period from 5 June to 20 September of this year. Before presenting the report, I would like to note the recent agreements between Israel, the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. The Secretary-General welcomes these agreements, which suspended Israeli annexation plans over parts of the occupied West Bank. The Secretary-General hopes that these developments will encourage Palestinian and Israeli leaders to re-engage in meaningful negotiations toward a two-State solution and will create opportunities for regional cooperation. He reiterates that only a two-State solution that realizes the legitimate national aspirations of Palestinians and Israelis can lead to sustainable peace between the two peoples and contribute to broader peace in the region. I am similarly encouraged by the call to restore hope in the peace process and resume negotiations on the basis of international law and agreed parameters, as made by the Foreign Ministers of Jordan, Egypt, France and Germany in Amman. The recent moves toward strengthening Palestinian unity as demonstrated by the outcome of the Fatah-Hamas meetings calling for long-awaited national presidential and legislative elections are also encouraging. Elections and legitimate democratic institutions are critical to uniting Gaza and the West Bank under a single national authority vital to upholding the prospect of a negotiated two-State solution. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Israel and the Occupied Territories 2014 Human

ISRAEL 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multi-party parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, the parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “State of Emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve the government and mandate elections. The nationwide Knesset elections in January 2013, considered free and fair, resulted in a coalition government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Security forces reported to civilian authorities. (An annex to this report covers human rights in the occupied territories. This report deals with human rights in Israel and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.) During the year a number of developments affected both the Israeli and Palestinian populations. From July 8 to August 26, Israel conducted a military operation designated as Operation Protective Edge, which according to Israeli officials responded to increases in the number of rockets deliberately fired from Gaza at Israeli civilian areas beginning in late June, as well as militants’ attempts to infiltrate the country through tunnels from Gaza. According to publicly available data, Hamas and other militant groups fired 4,465 rockets and mortar shells into Israel, while the government conducted 5,242 airstrikes within Gaza and a 20-day military ground operation in Gaza. According to the United Nations, the operation killed 2,205 Palestinians. The Israeli government estimated that half of those killed were civilians and half were combatants, according to an analysis of data, while the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs recorded 1,483 civilian deaths--more than two-thirds of those killed--including 521 children and 283 women; 74 persons in Israel were killed, among them 67 combatants, six Israeli civilians, and one Thai civilian. -

Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza

WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A N H Z И O E P W O I T E D N E Z I A M I C O N O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza LUCAS WINTER Open Source, Foreign Perspective, Underconsidered/Understudied Topics The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is an open source research organization of the U.S. Army. It was founded in 1986 as an innovative program that brought together military specialists and civilian academics to focus on military and security topics derived from unclassified, foreign media. Today FMSO maintains this research tradition of special insight and highly collaborative work by conducting unclassified research on foreign perspectives of defense and security issues that are understudied or unconsidered. Author Background Mr. Winter is a Middle East analyst for the Foreign Military Studies Office. He holds a master’s degree in international relations from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and was an Arabic Language Flagship Fellow in Damascus, Syria, in 2006–2007. Previous Publication This paper was originally published in the September-December 2017 issue of Engineer: the Professional Bulletin for Army Engineers. It is being posted on the Foreign Military Studies Office website with permission from the publisher. FMSO has provided some editing, format, and graphics to this paper to conform to organizational standards. -

The Upper Kidron Valley

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi Jerusalem 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study No. 398 The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi This publication was made possible thanks to the assistance of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, San Francisco. 7KHFRQWHQWRIWKLVGRFXPHQWUHÀHFWVWKHDXWKRUV¶RSLQLRQRQO\ Photographs: Maya Choshen, Israel Kimhi, and Flash 90 Linguistic editing (Hebrew): Shlomo Arad Production and printing: Hamutal Appel Pagination and design: Esti Boehm Translation: Sagir International Translations Ltd. © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., Jerusalem 92186 http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] Research Team Israel Kimhi – head of the team and editor of the report Eran Avni – infrastructures, public participation, tourism sites Amir Eidelman – geology Yair Assaf-Shapira – research, mapping, and geographical information systems Malka Greenberg-Raanan – physical planning, development of construction Maya Choshen – population and society Mike Turner – physical planning, development of construction, visual analysis, future development trends Muhamad Nakhal ±UHVLGHQWSDUWLFLSDWLRQKLVWRU\SUR¿OHRIWKH$UDEQHLJKERU- hoods Michal Korach – population and society Israel Kimhi – recommendations for future development, land uses, transport, planning Amnon Ramon – history, religions, sites for conservation Acknowledgments The research team thanks the residents of the Upper Kidron Valley and the Visual Basin of the Old City, and their representatives, for cooperating with the researchers during the course of the study and for their willingness to meet frequently with the team. -

A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution WATCH A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org APRIL 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-900-1 A Threshold Crossed Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution Map .................................................................................................................................. i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Definitions of Apartheid and Persecution ................................................................................. -

Reviving the Stalled Reconstruction of Gaza

Policy Briefing August 2017 Still in ruins: Reviving the stalled reconstruction of Gaza Sultan Barakat and Firas Masri Still in ruins: Reviving the stalled reconstruction of Gaza Sultan Barakat and Firas Masri The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha Still in ruins: Reviving the stalled reconstruction of Gaza Sultan Barakat and Firas Masri1 INTRODUCTION Israelis and Palestinians seems out of reach, the humanitarian problems posed by the Three years have passed since the conclusion substandard living conditions in Gaza require of the latest military assault on the Gaza Strip. the attention of international actors associated Most of the Palestinian enclave still lies in ruin. with the peace process. If the living conditions Many Gazans continue to lack permanent in Gaza do not improve in the near future, the housing, living in shelters and other forms of region will inevitably experience another round temporary accommodation. -

Legal Memo: Applying for a Building Permit in East Jerusalem

February 2017 1 Legal Memo Applying for a Building Permit in East Jerusalem OBJECTIVE: This fact sheet describes the procedures involved in applying for a building permit in occupied East Jerusalem. Numerous documents and procedural obligations are required in order to receive a building permit under Israeli planning regulations in effect in East Jerusalem. Detailed here are the particular constraints Palestinian residents face in undertaking these application procedures, which make obtaining a building permit almost impossible. A prerequisite to the authorisation of any building permit is the existence of an approved planning scheme. Therefore, this fact sheet also details the planning process and provides an overview of the steps involved in submitting both planning schemes and building permit applications. Background Under the Israeli Planning and Building Law 1965, a building permit issued by the Jerusalem Local Planning and Building Committee is a mandatory prerequisite for any construction within the municipal borders of Jerusalem, including annexed East Jerusalem. The law stipulates that any construction of a building without a permit is a criminal offence. Consequently, the building can be subject to a demolition order and the builder will be subject to an indictment. According to international law and the consensus of the international community on the matter, East Jerusalem is occupied territory and subject to the relevant laws of occupation.1 However, Israel, which unilaterally annexed East Jerusalem in 1967 and formally codified the annexation in 1980, considers East Jerusalem as Israeli territory and subjects it to Israeli jurisdiction.2 According to Israeli authorities, therefore, Israeli planning and building laws apply identically to East and West Jerusalem and elsewhere in Israel.