Module 1: Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agentive and Patientive Verb Bases in North Alaskan Inupiaq

AGENTTVE AND PATIENTIVE VERB BASES IN NORTH ALASKAN INUPIAQ A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By TadatakaNagai, B.Litt, M.Litt. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2006 © 2006 Tadataka Nagai Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3229741 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3229741 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. AGENTIVE AND PATIENTIYE VERB BASES IN NORTH ALASKAN INUPIAQ By TadatakaNagai ^ /Z / / RECOMMENDED: -4-/—/£ £ ■ / A l y f l A £ y f 1- -A ;cy/TrlHX ,-v /| /> ?AL C l *- Advisory Committee Chair Chair, Linguistics Program APPROVED: A a r// '7, 7-ooG Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. iii Abstract This dissertation is concerned with North Alaskan Inupiaq Eskimo. -

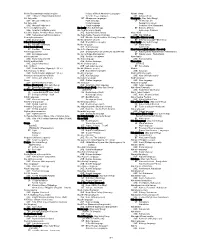

Download the Original Language Map in PDF Format

Aleut Copper Island (Unangam Tunuu) Attuan Creole Aleut (Unangam Tunuu) Taz Itelmen Evenk Ulchi Even Nanai Orok (Uilta)Orochi Udege Nanai Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) Alyutor Nivkh Ulchi Central Alaskan Yupik Kerek Koryak Negidal Haida Deg Xinag Sirenik Naukan Yupik Chuvan Eyak Kuskokwim Evenk Ahtna Central Siberian Even Dena'ina Holikachuk Yupik Even Tsimshianic Tlingit Chukchi Kolyma Evenk Tsetsaut Tanacross Yukagir Nisga-Gitksan Tagish Tanana Koyukon Chukchi Tutchone Hän Iñupiaq Tundra Sakha Kaska Yukagir (Yakut) Gwich’in Evenk Even Sakha North Slavey (Yakut) South Slavey Inuvialuktun Evenk Tłıchǫ Evenk Chipewyan Inuinnaqtun Soyot Dolgan Ket Tofa Tuvan Evenk Nanai Kivallirmiutut Natsilingmiutut Nganasan Shor Chelkan Nenets Enets Telengit Aivilingmiutut Evenk Teleut Kumandin Qikiqtaaluk uannangani Selkup Chulym Tuba Inuktun Selkup Nenets Qikiqtaaluk nigiani Khanty Mansi Nunavimmiutitut Nenets Nunatsiavummiutut Izhma-Komi Kalaallisut Skolt Sámi Ter Sámi Komi Kildin Sámi Inari Sámi Akkala Sámi Iivermiisud Northern Sámi Kemi Sámi Lule Sámi Karelian Pite Sámi Veps Ume Sámi Altaic family Southern Sámi Na'Dene family Turkic branch Athabaskan branch Mongolic branch Eyak branch Tunguso-Manchurian branch Tlingit branch Paleo-Asian family Eskaleut family Paleo-Asian family Inuit group of Inuit-Yupik branch Language isolates Uralic family Yupik group of Inuit-Yupik branch Ket Finno-Ugric branch Aleut (Unangam Tunuu) branch Nivkh Samoyedic branch Not represented by Permanent Participants Tsimshianic Critically endangered or recently extinct Haida languages Dialects Yukagir languages. -

Paleo-Asian Family Na'dene Family Eskaleut Family Uralic Family Altaic

Aleut Copper Island (Unangam Tunuu) Attuan Creole Aleut (Unangam Tunuu) Taz Itelmen Evenk Ulchi Even Nanai Orok (Uilta)Orochi Udege Nanai Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) Alyutor Nivkh Ulchi Central Alaskan Yupik Kerek Koryak Negidal Haida Deg Xinag Sirenik Naukan Yupik Chuvan Eyak Kuskokwim Evenk Ahtna Central Siberian Even Dena'ina Holikachuk Yupik Even Tsimshianic Tlingit Chukchi Kolyma Evenk Tsetsaut Tanacross Yukagir Nisga-Gitksan Tagish Tanana Koyukon Chukchi Tutchone Hän Iñupiaq Tundra Sakha Kaska Yukagir (Yakut) Gwich’in Evenk Even Sakha North Slavey (Yakut) South Slavey Inuvialuktun Evenk Tłıchǫ Evenk Chipewyan Inuinnaqtun Soyot Dolgan Ket Tofa Tuvan Evenk Nanai Kivallirmiutut Natsilingmiutut Nganasan Shor Chelkan Nenets Enets Telengit Aivilingmiutut Evenk Teleut Kumandin Qikiqtaaluk uannangani Selkup Chulym Tuba Inuktun Selkup Nenets Qikiqtaaluk nigiani Khanty Mansi Nunavimmiutitut Nenets Nunatsiavummiutut Izhma-Komi Kalaallisut Skolt Sámi Ter Sámi Komi Kildin Sámi Inari Sámi Akkala Sámi Iivermiisud Northern Sámi Kemi Sámi Lule Sámi Karelian Pite Sámi Veps Ume Sámi Altaic family Southern Sámi Na'Dene family Turkic branch Athabaskan branch Mongolic branch Eyak branch Tunguso-Manchurian branch Tlingit branch Paleo-Asian family Eskaleut family Paleo-Asian family Inuit group of Inuit-Yupik branch Language isolates Uralic family Yupik group of Inuit-Yupik branch Ket Finno-Ugric branch Aleut (Unangam Tunuu) branch Nivkh Samoyedic branch Not represented by Permanent Participants Tsimshianic Critically endangered or recently extinct Haida languages Dialects Yukagir languages. -

İnyupikçe Bitki Ve Hayvan Adları ÜMÜT ÇINAR Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names

İnyupikçe Bitki ve Hayvan Adları Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names Niġrutillu Nautchiallu I (Mammals & Birds) ✎ Ümüt Çınar Nisan 2017 KEÇİÖREN / ANKARA Turkey Kmoksy www.kmoksy.com www.kmoksy.com Sayfa 1 İnyupikçe Bitki ve Hayvan Adları ÜMÜT ÇINAR Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names The re-designed images or collages (mostly taken from the Wikipedia) are not copyrighted and may be freely used for any purpose Iñupiaq (ipk = esi & esk)-speaking Area www.kmoksy.com Sayfa 2 İnyupikçe Bitki ve Hayvan Adları ÜMÜT ÇINAR Iñupiaq Plant and Animal Names Eskimo-Aleut dilleri içinde İnyupikçenin konumu Eskimo - Aleut dilleri 1. Eskimo - Aleut languages Aleutça (Unanganca) 1.1. Aleut (Unangan) Eskimo dilleri 1.2. Eskimo languages Yupik dilleri 1.2.1. Yupik languages Sirenik Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1. Sireniki language Öz Yupik dilleri 1.2.1.1. Yupik proper Sibirya Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.1. Siberian Yupik Naukan Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.2. Naukan Yupik Alaska Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. Central Alaskan Yup'ik Unaliq-Pastuliq Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. 1. Norton Sound Yup'ik Yupikçe 1.2.1.1.3. 2. Yukon and Kuskokwin Yup'ik Egegik Yupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. 3. Bristol Bay Yup'ik Çupikçe 1.2.1.1.3. 4. Hooper Bay and Chevak Cup'ik Nunivak Çupikçesi 1.2.1.1.3. 5. Nunivak Cup'ig Supikçe 1.2.1.1.4. Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) İnuit dilleri 1.2.2. Inuit languages İnyupikçe 1.2.2.1. Inupiaq Batı Kanada İnuitçesi 1.2.2.2. Western Canadian Inuit (Inuvialuktun) Doğu Kanada İnuitçesi 1.2.2.3. -

Proto-Inuit Phonology

* Proto-Inuit Phonology Doug Hitch Independent Scholar Proto-Inuit and the daughter dialects have two non-nasal, non- lateral consonant series, /p t c k q/ and /v ʐ j ɣ ʁ/. The distinctive feature separating these sets has been generally regarded as continuance but voicing is a better candidate. PI *c has been seen as affricate [ts] or [tʃ] but a voiceless palatal stop value [c] better explains the diachronic and synchronic data. PI *ʐ and modern /ʐ/ have received a wide range of phonetic characterizations but a voiced retroflex sibilant value [ʐ] best accounts for the historical and descriptive evidence. Some historical documents and modern descriptions are reassessed. Some suggestions are made for the reconstruction of PI. 1 Introduction The Inuit language family stretches from Big Diomede Island in the Bering Strait to the east coast of Greenland. Probably all of the many intervening dialects have been studied, and while the studies have varying degrees of depth, there is no doubt about the basic identity of the phonemic units for any dialect and there is much known about phonological and morphophonological patterning. With the numerous distinct dialects, and the existence of much historical documentation, the language area offers a rich field for historical linguistics and linguistic typology. In these pages much effort is made towards refining our phonetic understanding of the segments /c/ and /ʐ/ in both Proto-Inuit and the daughter dialects. This information has both diachronic and synchronic implications. It can simplify both descriptions and make them more natural. Also presented here is a fresh look at the distinctive feature specification of the consonants. -

*‡Table 6. Languages

T6 Table[6.[Languages T6 T6 DeweyT6iDecima Tablel[iClassification6.[Languages T6 *‡Table 6. Languages The following notation is never used alone, but may be used with those numbers from the schedules and other tables to which the classifier is instructed to add notation from Table 6, e.g., translations of the Bible (220.5) into Dutch (—3931 in this table): 220.53931; regions (notation —175 from Table 2) where Spanish language (—61 in this table) predominates: Table 2 notation 17561. When adding to a number from the schedules, always insert a decimal point between the third and fourth digits of the complete number Unless there is specific provision for the old or middle form of a modern language, class these forms with the modern language, e.g., Old High German —31, but Old English —29 Unless there is specific provision for a dialect of a language, class the dialect with the language, e.g., American English dialects —21, but Swiss-German dialect —35 Unless there is a specific provision for a pidgin, creole, or mixed language, class it with the source language from which more of its vocabulary comes than from its other source language(s), e.g., Crioulo language —69, but Papiamento —68. If in doubt, prefer the language coming last in Table 6, e.g., Michif —97323 (not —41) The numbers in this table do not necessarily correspond exactly to the numbers used for individual languages in 420–490 and in 810–890. For example, although the base number for English in 420–490 is 42, the number for English in Table 6 is —21, not —2 (Option A: To give local emphasis and a shorter number to a specific language, place it first by use of a letter or other symbol, e.g., Arabic language 6_A [preceding 6_1]. -

Comment Les Inuvialuit Parlent De Leur Passé Note De Recherche How the Inuvialuit Talk About Their Past Murielle Nagy

Document generated on 09/29/2021 5:37 a.m. Anthropologie et Sociétés Comment les Inuvialuit parlent de leur passé Note de recherche How the Inuvialuit Talk about Their Past Murielle Nagy Mémoires du Nord Article abstract Volume 26, Number 2-3, 2002 This paper is a series of reflections on how Inuvialuit talk about their past and on the problems associated in interpreting translations. While analyzing URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/007055ar interviews done with Inuvialuit elders during oral history projects, it was DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/007055ar noticed that they use different ways to evoke the past, and that it is difficult to translate all the nuances of Inuit language into English. Remembrance varies See table of contents according to gender, it relies on spatial rather than temporal markers, revealing a peculiar conception of early childhood. Publisher(s) Département d’anthropologie de l’Université Laval ISSN 0702-8997 (print) 1703-7921 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this note Nagy, M. (2002). Comment les Inuvialuit parlent de leur passé : note de recherche. Anthropologie et Sociétés, 26(2-3), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.7202/007055ar Tous droits réservés © Anthropologie et Sociétés, Université Laval, 2002 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. -

A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska

Agentive And Patientive Verb Bases In North Alaskan Inupiaq Item Type Thesis Authors Nagai, Tadataka Download date 08/10/2021 07:18:20 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/8897 AGENTTVE AND PATIENTIVE VERB BASES IN NORTH ALASKAN INUPIAQ A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By TadatakaNagai, B.Litt, M.Litt. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2006 © 2006 Tadataka Nagai Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3229741 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3229741 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. AGENTIVE AND PATIENTIYE VERB BASES IN NORTH ALASKAN INUPIAQ By TadatakaNagai ^ /Z / / RECOMMENDED: -4-/—/£ £ ■ / A l y f l A £ y f 1- -A ;cy/TrlHX ,-v /| /> ?AL C l *- Advisory Committee Chair Chair, Linguistics Program APPROVED: A a r// '7, 7-ooG Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Orality, Literacy and Social Approach of Language

15e Congrès des Etudes Inuit, Oralité / 15th Inuit Studies Conference, Orality Résumé des communications, par sessions / Papers abstracts, sorted by sessions Orality and Literacy .................................................................................................................... 1 Inuit Culture and Literature - Echoing Inuit Voices? ................................................................ 11 Recollecting and Sharing Specific Experiences ........................................................................ 13 Arctic History: Tracking Words and People, and their Stories ................................................. 19 Narration in the Media and in Cyberspace .............................................................................. 21 Communicating through Play, Interacting through Games ..................................................... 26 Marcel Mauss' 100 years Later ................................................................................................ 28 Inuit Naming Practices ............................................................................................................. 30 Uumajuit: talking about and sharing the game ....................................................................... 32 Webs of Meaning: .................................................................................................................... 36 the Interconnectedness of Talk and Objects ........................................................................... 36 Webs of Meaning: Iñupiaq (and -

Indigenous Peoples Have Inhabited the Area for Tens Turkic Branch 7Ąófkr of Thousands of Years

ARCTIC INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES Aleut Copper Island (Unangam Tunuu) Attuan Creole Aleut (Unangam Tunuu) Itelmen Taz Evenk Ulchi Did you know? Even Nanai Orochi Udege Paleo-Asian family At least 43% of the estimated Orok (Uilta) 6000 languages spoken in the Nanai TELLING THE STORY Sugpiaq (Alutiiq) Alyutor Ulchi world are endangered. Nivkh UNESCO Central Alaskan Yupik Koryak Kerek Negidal Deg Xinag Haida Sirenik Naukan Yupik P Eskimo Chuvan Y Eyak Kuskokwim Evenk A L Ahtna Central Siberian Even L I Holikachuk Kolyma Tsimshianic Dena'ina Yupik Even E M Tlingit Chukchi Yukagir Evenk O A Tsetsaut -A F Tanacross SIAN Chukchi Nisga-Gitksan Tagish Tanana Koyukon Iñupiaq Tutchone Hän Sakha THE REGION Tundra (Yakut) Kaska Yukagir Gwich’in The Arctic is comprised of the northernmost Evenk parts of eight countries: Canada, Denmark, Sakha Athabaskan branch (Yakut) Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the North Slavey Even United States. Eyak branch South Slavey Inuvialuktun Evenk Tlingit branch Indigenous peoples have inhabited the area for tens Turkic branch 7ĄóFKR of thousands of years. Today, there are approx- Evenk Mongolic branch imately four million inhabitants in the circumpolar Arctic, and approximately 10% of the total Chipewyan Inuinnaqtun Tunguso-Manchurian branch N Soyot population is Indigenous. A LY ’DE MI More than 40 Indigenous languages are spoken in N FA Dolgan Ket E Tofa Tuvan the Arctic; even more, if dialects are classified as Evenk Nanai languages of their own. Arctic Indigenous languages Kivallirmiutut A LY belong to the: Na’Dene, Eskaleut, Uralic, Paleo-Asian LT I Natsilingmiutut A M IC FA and Altaic families. -

LCSH Section N

N-(3-trifluoromethylphenyl)piperazine Indians of North America—Languages Na'ami sheep USE Trifluoromethylphenylpiperazine West (U.S.)—Languages USE Awassi sheep N-3 fatty acids NT Athapascan languages Naamyam (May Subd Geog) USE Omega-3 fatty acids Eyak language UF Di shui nan yin N-6 fatty acids Haida language Guangdong nan yin USE Omega-6 fatty acids Tlingit language Southern tone (Naamyam) N.113 (Jet fighter plane) Na family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ballads, Chinese USE Scimitar (Jet fighter plane) Na Guardis Island (Spain) Folk songs, Chinese N.A.M.A. (Native American Music Awards) USE Guardia Island (Spain) Naar, Wadi USE Native American Music Awards Na Hang Nature Reserve (Vietnam) USE Nār, Wādī an N-acetylhomotaurine USE Khu bảo tồn thiên nhiên Nà Hang (Vietnam) Naʻar (The Hebrew word) USE Acamprosate Na-hsi (Chinese people) BT Hebrew language—Etymology N Bar N Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi (Chinese people) Naar family (Not Subd Geog) BT Ranches—Montana Na-hsi language UF Nahar family N Bar Ranch (Mont.) USE Naxi language Narr family BT Ranches—Montana Na Ih Es (Apache rite) Naardermeer (Netherlands : Reserve) N-benzylpiperazine USE Changing Woman Ceremony (Apache rite) UF Natuurgebied Naardermeer (Netherlands) USE Benzylpiperazine Na-ion rechargeable batteries BT Natural areas—Netherlands n-body problem USE Sodium ion batteries Naas family USE Many-body problem Na-Kara language USE Nassau family N-butyl methacrylate USE Nakara language Naassenes USE Butyl methacrylate Ná Kê (Asian people) [BT1437] N.C. 12 (N.C.) USE Lati (Asian people) BT Gnosticism USE North Carolina Highway 12 (N.C.) Na-khi (Chinese people) Nāatas N.C. -

Across Inuit Dialects

Canadian Journal of Linguistics/Revue canadienne de linguistique 56(2): 203–228, 2011 Palatalization and “strong i” across Inuit dialects RICHARD COMPTON and B. ELAN DRESHER University of Toronto 1. INTRODUCTION Proto-Eskimo had four vowels, */i, @,a,u/(Fortescueetal.1994).Theysurvive as distinct vowels in the Yupik branch of Eskimo but, apart from some subdialects of Alaskan Inupiaq, no surface [@]remainsintheInuitbranch.InmostInuitdia- lects, this vowel merged with the reflexes of */i/. However, some Inuit dialects show palatalization after surface [i] corresponding to original */i/, but not after surface [i] corresponding to */@/(Dorais2003:33).Inthesedialectsitistraditionaltodistin- guish between “strong i”, which descends from */i/ and causes palatalization, and “weak i”, which descends from */@/anddoesnot. In the other Inuit dialects the original distinction between */i/ and */@/hasbeen lost. It is interesting that none of these dialects show palatalization. We will show that there is evidence that some of these dialects once had palatalization following */i/; the merger of non-palatalizing */@/with*/i/resultedinthelossofpalatalization in these dialects. It might be expected that there would be a few dialects in which palatalization was generalized to be triggered by every surface [i], but there are no such dialects. Rather, the presence of palatalization must co-occurwith an underlying contrast between /i/ and a fourth vowel. Why is this so? The lack of palatalization in any of the three-vowel dialects is a striking fact that needs to be explained. We propose that the lack of palatalization in three-vowel dialects follows from certain assumptions about contrast and phonological activity. In brief, we argue that the contrastive status of a vowel /i/ in a four-vowel system is fundamentally different from its status in a three-vowel system.