Genetic Origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paleolithic Y-Haplogroup Heritage Predominates in a Cretan Highland Plateau

European Journal of Human Genetics (2007) 15, 485–493 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1018-4813/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Paleolithic Y-haplogroup heritage predominates in a Cretan highland plateau Laisel Martinez1, Peter A Underhill2, Lev A Zhivotovsky3, Tenzin Gayden1, Nicholas K Moschonas4, Cheryl-Emiliane T Chow2, Simon Conti2, Elisabetta Mamolini5, L Luca Cavalli-Sforza2 and Rene J Herrera*,1 1Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA; 2Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA; 3N.I. Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia; 4Department of Biology, University of Crete, Crete, Greece; 5Department of Biology, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy The island of Crete, credited by some historical scholars as a central crucible of western civilization, has been under continuous archeological investigation since the second half of the nineteenth century. In the present work, the geographic stratification of the contemporary Cretan Y-chromosome gene pool was assessed by high-resolution haplotyping to investigate the potential imprints of past colonization episodes and the population substructure. In addition to analyzing the possible geographic origins of Y-chromosome lineages in relatively accessible areas of the island, this study includes samples from the isolated interior of the Lasithi Plateau – a mountain plain located in eastern Crete. The potential significance of the results from the latter region is underscored by the possibility that this region was used as a Minoan refugium. Comparisons of Y-haplogroup frequencies among three Cretan populations as well as with published data from additional Mediterranean locations revealed significant differences in the frequency distributions of Y-chromosome haplogroups within the island. -

Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Management of Water Resources in the Island of Crete, Greece

water Review Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Management of Water Resources in the Island of Crete, Greece V. A. Tzanakakis 1,2,*, A. N. Angelakis 3,4 , N. V. Paranychianakis 5, Y. G. Dialynas 6 and G. Tchobanoglous 7 1 Hellenic Agricultural Organization Demeter (HAO-Demeter), Soil and Water Resources Institute, 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 2 Department of Agriculture, School of Agricultural Science, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklion, 71410 Crete, Greece 3 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion, Greece 4 Union of Water Supply and Sewerage Enterprises, 41222 Larissa, Greece; [email protected] 5 School of Environmental Engineering, Technical University of Crete, 73100 Chania, Greece; [email protected] 6 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Cyprus, Nicosia 1678, Cyprus; [email protected] 7 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Davis, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 April 2020; Accepted: 16 May 2020; Published: 28 May 2020 Abstract: Crete, located in the South Mediterranean Sea, is characterized by long coastal areas, varied terrain relief and geology, and great spatial and inter-annual variations in precipitation. Under average meteorological conditions, the island is water-sufficient (969 mm precipitation; theoretical water potential 3284 hm3; and total water use 610 hm3). Agriculture is by far the greatest user of water (78% of total water use), followed by domestic use (21%). Despite the high average water availability, water scarcity events commonly occur, particularly in the eastern-south part of the island, driven by local climatic conditions and seasonal or geographical mismatches between water availability and demand. -

Bonelli's Eagle and Bull Jumpers: Nature and Culture of Crete

Crete April 2016 Bonelli’s Eagle and Bull Jumpers: Nature and Culture of Crete April 9 - 19, 2016 With Elissa Landre Photo of Chukar by Elissa Landre With a temperate climate, Crete is more pristine than the mainland Greece and has a culture all its own. Crete was once the center of the Minoan civilization (c. 2700–1420 BC), regarded as the earliest recorded civilization in Europe. In addition to birding, we will explore several famous archeological sites, including Knossos and ancient Phaistos, the most important centers of Minoan times. Crete’s landscape is very special: defined by high mountain ranges, deep valleys, fertile plateaus, and caves (including the mythological birthplace of the ancient Greek god, Zeus) Rivers have cut deep, exceptionally beautiful gorges that create a rich presence of geological wealth and have been explored for their aromatic and medicinal plants since Minoan times. Populations of choughs, Griffon Vultures, Lammergeiers, and swifts nest on the steep cliffs. A fantastic variety of birds and plants are found on Crete: not only its resident bird species, which are numerous and include rare and endangered birds, but also the migrants who stop over on Crete during their journeys to and from Africa and Europe. The isolation of Crete from mainland Europe, Asia, and Africa is reflected in the diversity of habitats, flora, and avifauna. The richness of the surroundings results in an impressive bird species list and often unexpected surprises. For example, last year a Blue- cheeked Bee-eater, usually only seen in northern Africa and the Middle East, was spotted. Join us for this unusual and very special trip. -

Genetic Origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature23310 Genetic origins of the Minoans and Mycenaeans Iosif Lazaridis1,2*, Alissa Mittnik3,4*, Nick Patterson2,5, Swapan Mallick1,2,6, Nadin Rohland1, Saskia Pfrengle4, Anja Furtwängler4, Alexander Peltzer3,7, Cosimo Posth3,4, Andonis Vasilakis 8, P. J. P. McGeorge9, Eleni Konsolaki-Yannopoulou10, George Korres11, Holley Martlew12, Manolis Michalodimitrakis13, Mehmet Özsait14, Nesrin Özsait14, Anastasia Papathanasiou15, Michael Richards16, Songül Alpaslan Roodenberg1, Yannis Tzedakis17, Robert Arnott18, Daniel M. Fernandes19,20, Jeffery R. Hughey21, Dimitra M. Lotakis22, Patrick A. Navas22, Yannis Maniatis23, John A. Stamatoyannopoulos24,25,26, Kristin Stewardson1,6, Philipp Stockhammer3,27, Ron Pinhasi19,28, David Reich1,2,6, Johannes Krause3,4 & George Stamatoyannopoulos22,25 The origins of the Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean cultures mainland Greece, whose language, written in the Linear B script, was have puzzled archaeologists for more than a century. We have an early form of Greek13. Cretan influence in mainland Greece and assembled genome-wide data from 19 ancient individuals, including the later Mycenaean occupation of Crete link these two archaeological Minoans from Crete, Mycenaeans from mainland Greece, and their cultures, but the degree of genetic affinity between mainland and Cretan eastern neighbours from southwestern Anatolia. Here we show that populations is unknown. Greek is related to other Indo-European Minoans and Mycenaeans were genetically similar, having at least languages, leading to diverse theories tracing its earliest speakers from three-quarters of their ancestry from the first Neolithic farmers the seventh millennium down to ∼ 1600 bc, and proposing varying of western Anatolia and the Aegean1,2, and most of the remainder degrees of population change (Supplementary Information section 1). -

Exploring Eastern Crete

Exploring eastern Crete Plan Days 4 First time in Crete, I guess I should start from the eastern part. A bit of hiking, Chrissi island and Zakro! By: Bonnie_EN PLAN SUMMARY Day 1 1. Ierapetra About region/Main cities & villages 2. Chrissi Islet Nature/Beaches 3. Belegrina Nature/Beaches Day 2 1. Orino Gorge Nature/Gorges 2. Ammoudi Nature/Beaches 3. Makrigialos Nature/Beaches Day 3 1. Zakros Minoan Palace Culture/Archaelogical sites 2. Kato Zakros Nature/Beaches 3. Dead’s Gorge Nature/Gorges Day 4 1. Vai Nature/Beaches 2. Agios Nikolaos About region/Main cities & villages WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 1 Day 1 1. Ierapetra Απόσταση: Start - About region / Main cities & villages Χρόνος: - GPS: N35.0118955, W25.740745199999992 Note: Breakfast and buy supplies for the excursion to Chrissi 2. Chrissi Islet Απόσταση: not available - Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: - GPS: N34.874162, W25.69242399999996 Note: It looks more than great, don't forget my camera 3. Belegrina Απόσταση: not available - Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: - GPS: N34.876695270466335, W25.723740148779257 WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 2 Day 2 1. Orino Gorge Απόσταση: Start - Nature / Gorges Χρόνος: - GPS: N35.06482450148083, W25.919971336554 Note: food for picnic 2. Ammoudi Απόσταση: by car 17.9km Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: 25′ GPS: N35.02149753640775, W26.01497129345705 Note: I would definitely wish to reach this beach 3. Makrigialos Απόσταση: by car 4.9km Nature / Beaches Χρόνος: 05′ GPS: N35.03926672571038, W25.976804824914552 Note: alternative if there is not enough time to go to Ammoudi WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 3 Day 3 1. Zakros Minoan Palace Location: Zakros Culture / Archaelogical sites Contact: Tel: (+30) 28410 22462, 24943, 22382 Απόσταση: Note: How could I not go Start - Χρόνος: - GPS: N35.098203523045854, W26.261405940008558 2. -

Cretan Sanctuaries and Cults Religions in the Graeco-Roman World

Cretan Sanctuaries and Cults Religions in the Graeco-Roman World Editors H.S. Versnel D. Frankfurter J. Hahn VOLUME 154 Cretan Sanctuaries and Cults Continuity and Change from Late Minoan IIIC to the Archaic Period by Mieke Prent BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 This series Religions in the Graeco-Roman World presents a forum for studies in the social and cul- tural function of religions in the Greek and the Roman world, dealing with pagan religions both in their own right and in their interaction with and influence on Christianity and Judaism during a lengthy period of fundamental change. Special attention will be given to the religious history of regions and cities which illustrate the practical workings of these processes. Enquiries regarding the submission of works for publication in the series may be directed to Professor H.S. Versnel, Herenweg 88, 2361 EV Warmond, The Netherlands, [email protected]. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prent, Mieke. Cretan sanctuaries and cults : continuity and change from Late Minoan IIIC to the Archaic period / by Mieke Prent. p. cm. — (Religions in the Graeco-Roman world, ISSN 0927-7633 ; v. 154) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-14236-3 (alk. paper) 1. Crete (Greece)—Religion. 2. Shrines—Greece—Crete. 3. Crete (Greece)— Antiquities. I. Title. II. Series. BL793.C7P74 2005 292.3'5'09318—dc22 2004062546 ISSN 0927–7633 ISBN 90 04 14236 3 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

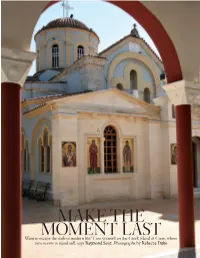

D8B< K?< DFD<EK C8JK

D8B<K?< DFD<EKC8JK NXekkf\jZXg\k_\ilj_f]df[\iec`]\6Cfj\pflij\c]fek_\>i\\b`jcXe[f]:i\k\#n_\i\ k`d\j\\djkfjkXe[jk`cc#jXpjIXpdfe[J\`kq%G_fkf^iXg_jYpI\Y\ZZX;lb\ TR30167_V2.indd 3 16/4/09 10:07:19 JLDD<IFE:I<K< WHERE TO STAY farmhouse. Three OAmirandes gorgeous guesthouses, The latest hotel from each with its own Grecotel, Greece’s pool, are set on an largest hotel chain, is organic farm shaded also the classiest. With by palms and lilac 212 rooms, suites and blossoms. Original bungalows around a arches, stone walls lagoon, this is a five- and porthole windows star resort with knobs are offset by fine on. It has an Ayurvedic antiques and hand- spa, six restaurants, crafted furniture. more than 60 private Kitchens are stocked pools and lots of daily with local treats family activities. and fruit from the farm Good for: – the strawberries are A real splurge famous all over Greece. 00 30 28970 41103; Good for: www.amirandes.com. A romantic retreat Doubles from €180 00 30 28210 41321; OAmmos Hotel www.metohi-kindelis.gr. A welcome splash of Guesthouse for two style among the drab from €180, breakfast resorts west of Chania, supplies and daily this seaside hotel has maid service included a whitewashed exterior OKalimera concealing bold colours Archanes Village and striking details To beat the tour buses within: Bisazza tiles, that descend on Marimekko fabrics and Knossos daily, check Paola Navone chairs. into this complex of Owner Nikos Tsepetis three stone villas a makes a point of 15-minute drive away. -

Fhu2xellcj7lgbnexipovzl4g6a.Pdf

Griechenland Attika...................................................................................................................................................4 Athen-Zentrum.....................................................................................................................................4 Athen-Nord...........................................................................................................................................5 Athen-Süd.............................................................................................................................................6 Athen-West...........................................................................................................................................7 Piräus....................................................................................................................................................8 Inseln....................................................................................................................................................9 Ostattika..............................................................................................................................................10 Westattika............................................................................................................................................11 Epirus.................................................................................................................................................12 Arta.....................................................................................................................................................12 -

Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials

MORTUARY VARIABILITY IN EARLY IRON AGE CRETAN BURIALS Melissa Suzanne Eaby A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Donald C. Haggis Carla M. Antonaccio Jodi Magness G. Kenneth Sams Nicola Terrenato UMI Number: 3262626 Copyright 2007 by Eaby, Melissa Suzanne All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3262626 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 © 2007 Melissa Suzanne Eaby ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MELISSA SUZANNE EABY: Mortuary Variability in Early Iron Age Cretan Burials (Under the direction of Donald C. Haggis) The Early Iron Age (c. 1200-700 B.C.) on Crete is a period of transition, comprising the years after the final collapse of the palatial system in Late Minoan IIIB up to the development of the polis, or city-state, by or during the Archaic period. Over the course of this period, significant changes occurred in settlement patterns, settlement forms, ritual contexts, and most strikingly, in burial practices. Early Iron Age burial practices varied extensively throughout the island, not only from region to region, but also often at a single site; for example, at least 12 distinct tomb types existed on Crete during this time, and both inhumation and cremation were used, as well as single and multiple burial. -

Crete (Chapter)

Greek Islands Crete (Chapter) Edition 7th Edition, March 2012 Pages 56 Page Range 256-311 PDF Coverage includes: Central Crete, Iraklio, Cretaquarium, Knossos, Arhanes, Zaros, Matala, Rethymno, Moni Arkadiou, Anogia, Mt Psiloritis, Spili, Plakias & around, Beaches Between Plakias & Agia Galini, Agia Galini, Western Crete, Hania & around, Samaria Gorge, Hora Sfakion & around, Frangokastello, Anopoli & Inner Sfakia, Sougia, Paleohora, Elafonisi, Gavdos Island, Kissamos-Kastelli & around, Eastern Crete, Lasithi Plateau, Agios Nikolaos & around, Mohlos, Sitia & around, Kato Zakros & Ancient Zakros, and Ierapetra & around. Useful Links: Having trouble viewing your file? Head to Lonely Planet Troubleshooting. Need more assistance? Head to the Help and Support page. Want to find more chapters? Head back to the Lonely Planet Shop. Want to hear fellow travellers’ tips and experiences? Lonely Planet’s Thorntree Community is waiting for you! © Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd. To make it easier for you to use, access to this chapter is not digitally restricted. In return, we think it’s fair to ask you to use it for personal, non-commercial purposes only. In other words, please don’t upload this chapter to a peer-to-peer site, mass email it to everyone you know, or resell it. See the terms and conditions on our site for a longer way of saying the above - ‘Do the right thing with our content. ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Crete Why Go? Iraklio ............................ 261 Crete (Κρήτη) is in many respects the culmination of the Knossos ........................268 Greek experience. Nature here has been as prolifi c as Picas- Rethymno ..................... 274 so in his prime, creating a dramatic quilt of big-shouldered Anogia ......................... -

Thehotel.Gr Travel Agency, +30 2821090760, Chania – Crete, Guide of Crete

TheHotel.gr Travel Agency, +30 2821090760, Chania – Crete, Guide of Crete TheHotel.gr Travel Agency Chania – Crete – Greece 41-43 Skalidi street, Chania +30 2821090760 [email protected] Guide of Crete http://www.thehotel.gr 0 TheHotel.gr Travel Agency, +30 2821090760, Chania – Crete, Guide of Crete CONTENTS CONTENTS ....................................................................................... 1 1. ABOUT THEHOTEL.GR TRAVEL AGENCY ........................................ 3 2. WHY BOOK WITH US .................................................................... 4 OUR COMPANY ........................................................................................ 4 YOU ARE OUR PRIORITY ......................................................................... 4 PERSONALIZED SERVICE ......................................................................... 4 EMPOWERMENT ....................................................................................... 4 SAVINGS ................................................................................................. 4 BOOK WITH CONFIDENCE AND SECURITY ............................................... 5 3. GREECE ........................................................................................ 6 4. CRETE .......................................................................................... 7 AREAS OF NATURAL BEAUTY ................................................................. 10 1. The White Mountains, Chania area ....................................................... 10 2. -

Crete 0 10 Miles

e# 0 20 km Crete 0 10 miles 36º N Archaeological Museum Marvel at treasures from ELEVATION ancient worlds 2000m 1500m Hania’s Old Town Rethymno’s Old Quarter Stroll the charming Experience the romance of 1000m Iraklio Wine Country Spinalonga Island 500m Venetian Harbour a Renaissance town SEA OF CRETE Sip Crete’s top Visit the leper colony turned 0 vintages tourist attraction Cape Spatha ä# Diktynna Moni Arkadiou Palace of Knossos Cape Rodopos Meditate on beauty and Walk in the footsteps of Vouxa Peninsula Gulf of the Minoans Gramvousa Moni Hania Stavros Moni Iannou Eremiti tragic history Islets Bay of #\ ä# Gonias Ü# Moni Governotou Bay of Kalathas Ü# GramvousaKissamos Ü# Vaï Beach Peninsula #\ Akrotiri Moni Agias Triadas Kissamos Kolymbari Peninsula #– Kick back under palm Falasarna #\ #\ #\ (Kastelli) Souda Bay trees #\ Platanias Hania #\ #\ #\ Voukolies Souda Cape Drapano Platanos ä# Cape Polyrrina Drapano Panormo Stavros Dia HANIA Peninsula #\ #\ Bali Almyros Bay #\ Rethymno Iraklio 33 Vryses #\ #\ Cape Agios Samaria Perama Moni Agia Omalos #\ Bay Iraklio Ioannis Cape #\ Gorge Georgioupolis Sideros Irini #\ Margarites #\ Axos ^# #– Hrysoskalitissas #\ National #\ Hersonisos Park Lake Episkopi Moni Ü# ä# Eleftherna ä# #\ Spinalonga Island Ü# Kandanos Lefka Ori ä## Malia R #\ Knossos #\ ä# #÷ Kournas#\ Arkadiou Sfendoni # Elounda (2453m) Argyroupoli #\ Kolokytha Moni #\ #\ Elafonisi # Samaria Cave Anogia Malia #\ Vaï 3Gorg3e Neapoli Peninsula Toplou #\ RETHYMNO Imbros Mt Psiloritis #\ Ü# #\ Sougia #\ Hora # Spili R Arhanes Ancient