RCED-98-151 Intercity Passenger Rail B-279203

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 71.9 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department 10-88 Bomb Threat 10-16 -

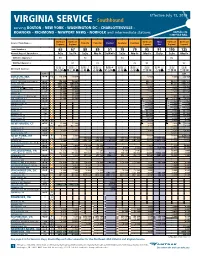

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

The ESPA EXPRESS NEWS from the EMPIRE STATE PASSENGERS ASSOCIATION

The ESPA EXPRESS NEWS FROM THE EMPIRE STATE PASSENGERS ASSOCIATION http://www.esparail.org WORKING FOR A MORE BALANCED TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM Vol. 35 No. 6 November/December 2011 Amtrak to Lease 85 Miles of Empire possibly changing the Lake Shore Limited schedule by departing Corridor from CSX Chicago 3 hours earlier and also departing New York about an hour earlier. One improvement considered would extend the In an extremely welcomed announcement, it was confirmed hours of the Diner to encourage more purchases, and to make on October 18 that Amtrak intends to enter into a long-term the Diner cashless (Debit/Credit cards only), which would save lease with CSX to gain full operational control of the 85 route time counting and tracking cash. Forty seven percent of the miles of the Empire Corridor between Control Point 75 north Diner guests are coach passengers, which is very high compared of Poughkeepsie (the north end of Metro-North territory) and to other Amtrak routes. Upgrading the food in the lounge car CP 160 at the Schenectady station. Amtrak already controls the also will be considered. Of interest in the report was that 62% 9 mile segment west of Schenectady to Hoffmans at CP 169 of the Lake Shore’s passengers are female and that 61% of where the CSX freight line from Selkirk Yard joins the main passengers are traveling alone. The top three city pairs on the line heading west. CSX will retain full freight rights on the Lake Shore Limited are: New York-Chicago, Buffalo-Chicago, leased line. and Syracuse-Chicago. -

Issue of Play on October 4 & 5 at the "The 6 :,53"

I the 'It, 980 6:53 OCTOBER !li AMTRAK... ... now serving BRYAN and LOVELAND ... returns to INDIA,NAPOLIS then turns em away Amtrak's LAKE SHORE LIMITED With appropriate "first trip" is now making regular stops inaugural festivities, Amtrak every day at BRYAN in north introduced daily operation of western Ohio. The westbound its new HOOSIER STATE on the train stops at 11:34am and 1st of October between IND the eastbound train stops at IANAPOLIS and CHICAGO. Sev 8:15pm. eral OARP members were on the Amtrak's SHENANDOAH inaugural trip, including Ray is now stopping daily at a Kline, Dave Marshall and Nick new station stop in suburban Noe. Complimentary champagne Cincinnati. The eastbound was served to all passengers SHENANDOAH stops at LOVELAND and Amtrak public affairs at 7:09pm and the westbound representatives passed out train stops at 8:15am. A m- Amtrak literature. One of trak began both new stops on the Amtrak reps was also pas Sunday, October 26th. Sev sing out OARP brochures! [We eral OARP members were on don't miss an opportunity!] hand at both stations as the Our members reported that the "first trains" rolled in. inaugural round trip was a OARP has supported both new good one, with on-time oper station stops and we are ation the whole way. Tracks glad they have finally come permit 70mph speeds much of about. Both communities are the way and the only rough supportive of their new Am track was noted near Chicago. trak service. How To Find Amtrak held another in its The Station Maps for both series of FAMILY DAYS with BRYAN qnd LOVELAND will be much equipment on public dis fopnd' inside this issue of play on October 4 & 5 at the "the 6 :,53". -

NORTHEAST CORRIDOR New York - Washington, DC

NORTHEAST CORRIDOR New York - Washington, DC September 5, 2017 NEW YORK and WASHINGTON, DC NEW YORK - NEWARK - TRENTON PHILADELPHIA - WILMINGTON BALTIMORE - WASHINGTON, DC and intermediate stations Acela Express,® Reserved Northeast RegionalSM and Keystone Service® THIS TIMETABLE SHOWS ALL AMTRAK SERVICE FROM BOSTON OR SPRINGFIELD TO POINTS NEW YORK THROUGH WASHINGTON, DC. Also see Timetable Form W04 for complete Boston/Springfield to Washington, DC schedules, and Timetable Form W06 for service to Virginia locations. FALL HOLIDAYS Special Thanksgiving timetables for the period, November 20 through 27, 2017, will appear on Amtrak.com shortly and temporarily supersede these schedules. 1-800-USA-RAIL Amtrak.com Amtrak is a registered service mark of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Washington Union Station, 60 Massachusetts Ave. N.E., Washington, DC 20002. NRPC Form W2–Internet only–9/5/17. Schedules subject to change without notice. Depart Depart Depart Depart Depart Arrive Depart Depart Depart Depart Depart Arrive Train Name/Number Frequency New York Newark Newark Intl. Air. Metropark Trenton Philadelphia Philadelphia Wilmington Baltimore BWI New Carrollton Washington Northeast Regional 67 Mo-Fr 3 25A 3 45A —— 4 00A 4 25A 4 52A 5 00A 5 22A 6 10A 6 25A 6 40A 7 00A Northeast Regional 151 Mo-Fr 4 40A R4 57A —— 5 12A 5 35A 6 04A 6 07A 6 28A 7 27A 7 40A D7 59A 8 14A Northeast Regional 111 Mo-Fr 5 30A R5 46A —— 6 00A 6 26A 6 53A 6 55A 7 15A 8 00A 8 15A D8 29A 8 50A Acela Express 2103 Mo-Fr -

Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

PB88-916301 NATIONAL TRANSPORT SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT REAR-END COLLISION OF AMTRAK PASSENGER TRAIN 94, THE COLONIAL AND CONSOLIDATED RAIL CORPORATION FREIGHT TRAIN ENS-121, ON THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR CHASE, MARYLAND JANUARY 4, 1987 NTSB/RAR-88/01 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2.Government Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/RAR-88/01 . PB88-916301 Title and Subtitle Railroad Accident Report^ 5-Report Date Rear-end Collision of'*Amtrak Passenger Train 949 the January 25, 1988 Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight -Performing Organization Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Code Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987 -Performing Organization 7. "Author(s) ~~ Report No. Performing Organization Name and Address 10.Work Unit No. National Transportation Safety Board Bureau of Accident Investigation .Contract or Grant No. Washington, D.C. 20594 k3-Type of Report and Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Iroad Accident Report lanuary 4, 1987 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 1*+.Sponsoring Agency Code 15-Supplementary Notes 16 Abstract About 1:16 p.m., eastern standard time, on January 4, 1987, northbound Conrail train ENS -121 departed Bay View yard at Baltimore, Mary1 and, on track 1. The train consisted of three diesel-electric freight locomotive units, all under power and manned by an engineer and a brakeman. Almost simultaneously, northbound Amtrak train 94 departed Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore. Train 94 consisted of two electric locomotive units, nine coaches, and three food service cars. In addition to an engineer, conductor, and three assistant conductors, there were seven Amtrak service employees and about 660 passengers on the train. -

March 25, 2019 Volume 39

MARCH 25, 2019 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 39 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 3 13 The Semaphore 17 David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Cape Cod News………………………………….Skip Burton Boston Herald Reporter……………………… Jim South 24 Boston Globe & Wall Street Journal Reporters Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Western Massachusetts………………………. Ron Clough Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart Mid-Atlantic News……………………………. Doug Buchanan PRODUCTION STAFF Publication…………….………………… …. … Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Bryan Miller Web Page …………………..………………… Savery Moore Club Photographer……………………………. Joe Dumas The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2019 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 39 ■■■■■ NUMBER 3 ■■■■■ MARCH 2019 CLUB OFFICERS BILL OF LADING President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Treasurer………………....Will Baker Book Review ........ ………12 Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Chief’s Corner ...... ……. .3 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Contests ................ ……….3 Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’20) ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘20) Clinic……………..………3 ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’19) Editor’s Notes. ….….....….12 …………………………...Gary Mangelinkx (‘19) Members ............... …….....12 Memories .............. ………..4 th Potpourri ............... ..…..…..5 ON THE COVER: March 9-10 Show Running Extra....... .….……13 and Open House memories. (Photos by Joe Dumas) 2 FORM 19 ORDERS Fred Lockhart MARCH B.O.D. -

Pennsylvanian and Early Permian Paleogeography of the Uinta-Piceance Basin Region, Northwestern Colorado and Northeastern Utah

Pennsylvanian and Early Permian Paleogeography of the Uinta-Piceance Basin Region, Northwestern Colorado and Northeastern Utah U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1 787-CC AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with the last offerings, are given in the current-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Survey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated monthly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey Books and Open-File Reports Sales, Box 25286, Denver, CO 80225. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL OVER THE COUNTER Books Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Tech Books of the U.S. Geological Survey are available over the niques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications counter at the following U.S. Geological Survey offices, all of of general interest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Documents. copies of periodicals (Earthquakes & Volcanoes, Preliminary De termination of Epicenters), and some miscellaneous reports, includ ANCHORAGE, Alaska-4230 University Dr., Rm. -

Crescent Corridor Update

Crescent Corridor Update December 21st, 2016 US DOT Talking Freight Norfolk Southern Government Relations Norfolk Southern’s Network • NS operates approximately 20,000 route miles throughout 22 states and the District of Columbia • Engaged in the rail transportation of raw materials, intermediate products, and finished goods • Operates the most extensive intermodal network in the East and is a major transporter of coal and industrial products. • NYSE: NSC 2 NS Intermodal Network Growth Majority of growth has been over Corridors • Norfolk Southern has A Network of Key Corridors employed a “Corridor Albany Boston Detroit Strategy” focusing on four Bethlehem Chicago New York/New Jersey Harrisburg Philadelphia key principles: Columbus Greencastle • Market access Cincinnati • Length of haul Charlotte Memphis • Asset utilization Atlanta Birmingham • Productivity Shreveport New Orleans What is an Intermodal Facility? Intermodal Facility –A rail terminal for transferring freight from one transportation mode to another, either from truck‐to‐rail or rail‐to‐truck for the Crescent Corridor, without the handling of the freight itself when changing modes. NS’ Intermodal Network Norfolk Southern System Intermodal Terminal(s) Market Expansions thru 2010 Market Expansions thru 2012 IM Port Terminal TCS Terminals Total U.S. Intermodal Units (Originated Units) 16,000,000 14,000,000 12,000,000 10,000,000 8,000,000 6,000,000 4,000,000 2,000,000 0 *2016 is Jan-Nov annualized Source: AAR Crescent Corridor Pre-Project Influences • Norfolk Southern – Continued cooperation with long-haul truck carriers – Increase in freight trade between Northeast and South – Infrastructure enhancements for speed and capacity • Key Drivers for Private, Local, State, and Federal Partners – Increased highway congestion and vehicular emissions – Growing vehicle travel miles and congestion on I-81, I- 40, I-85, I-20, and I-76. -

May 22, 2017 Volume 37

MAY 22, 2017 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 37 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 5 A Club in Transition 3 The Semaphore David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Cape Cod News………………………………….Skip Burton Boston Globe Reporter………………………. Brendan Sheehan Boston Herald Reporter……………………… Jim South Wall Street Journal Reporter....………………. Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli Empire State News…………………………… Dick Kozlowski Amtrak News……………………………. .. Rick Sutton, Russell Buck “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart PRODUCTION STAFF Publication………………………………… ….. Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Web Page …………………..…………………… Savery Moore Club Photographer……………………………….Joe Dumas The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2017 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 37 ■■■■■ NUMBER 5 ■■■■■ MAY 2017 CLUB OFFICERS BILL OF LADING President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Chief’s Corner ...... …….….4 Treasurer………………....Will Baker A Club in Transition….…..13 Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Contests ................ ………..4 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’18) Clinic……………..….…….7 ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘18) ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’17) Editor’s Notes. ….…....… .13 …………………………...Rick Sutton (‘17) Form 19 Orders .... ………..4 Members .............. ….…....14 Memories ............. .………..5 Potpourri .............. ..……….7 ON THE COVER: The first 25% of our building was Running Extra ..... -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A.