Tibetan Studies in Russia: a Brief Historical Account

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Introduction 6 Players (White first) and event Opening Page 1 Gelfand – Dreev, Tilburg 1993 Semi-Slav Defence [D48] 8 2 Benjamin – Anand, Groningen PCA 1993 Sicilian Defence [B63] 13 3 Karpov – Morovi‡, Las Palmas (1) 1994 Queen’s Gambit Declined [D32] 20 4 Adams – Agdestein, Oslo (2) 1994 Alekhine Defence [B02] 25 5 Yusupov – Dokhoian, Bundesliga 1993/4 Queen’s Gambit Declined [D31] 31 6 Gelfand – Hertneck, Munich 1994 Benko Gambit [A57] 37 7 Kasparov – P. Nikoli‡, Horgen 1994 French Defence [C18] 43 8 Karpov – Salov, Buenos Aires 1994 Sicilian Defence [B66] 50 9 Timman – Topalov, Moscow OL 1994 King’s Indian Defence [E87] 56 10 Shirov – Piket, Aruba (4) 1995 Semi-Slav Defence [D44] 60 11 Kasparov – Anand, Riga 1995 Evans Gambit [C51] 66 12 J. Polgar – Korchnoi, Madrid 1995 Caro-Kann Defence [B19] 71 13 Kramnik – Piket, Dortmund 1995 Catalan Opening [E05] 76 14 Kramnik – Vaganian, Horgen 1995 Queen’s Indian Defence [E12] 82 15 Shirov – Leko, Belgrade 1995 Ruy Lopez (Spanish) [C92] 88 16 Ivanchuk – Topalov, Wijk aan Zee 1996 English Opening [A26] 93 17 Khalifman – Short, Pärnu 1996 Queen’s Indian Defence [E12] 98 18 Kasparov – Anand, Amsterdam 1996 Caro-Kann Defence [B14] 104 19 Kasparov – Kramnik, Dos Hermanas 1996 Semi-Slav Defence [D48] 111 20 Timman – Van der Wiel, Dutch Ch 1996 Sicilian Defence [B31] 117 21 Svidler – Glek, Haifa 1996 French Defence [C07] 123 22 Torre – Ivanchuk, Erevan OL 1996 Sicilian Defence [B22] 128 23 Tiviakov – Vasiukov, Russian Ch 1996 Ruy Lopez (Spanish) [C65] 134 24 Illescas – -

Preface We Are Pleased to Present This Collection of Scholarly Articles of the International Scientific-Practical Conference «T

SHS Web of Conferences 8 9 , 00001 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20208900001 Conf-Corp 2020 Preface We are pleased to present this collection of scholarly articles of the International Scientific-Practical Conference «Transformation of Corporate Governance Models under the New Economic Reality» (CC-2020). The conference was held in Ural State University of Economics, Yekaterinburg, Russia, on November 20, 2020. The key topics of the Conference were: o A shift in the corporate governance paradigm in the context of the technological transformation and the coronavirus crisis; o Boards of Directors as drivers of business transformation in the new post-pandemic reality; o Modernization of the stakeholder approach in the development of corporate governance models, understanding of the interests of stakeholders and evaluation of their contribution to the formation of the value and social capital of the business; o The impact of new technologies (big data, artificial intelligence, neural networks) on the development and efficiency of corporate governance systems; o Coordination of the corporate governance system with new business formats: ecosystem, platform, distributed companies; o The impact of digitalization on the formation of strategic corporate interests of a company; o CSR and corporate strategies: problems of transformation to achieve sustainable development. The conference was attended in an online format by almost 70 participants from leading universities in 10 countries: Russia, Italy, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Moldova, Kazakhstan, DPR. The geography of Russian participants is also extensive - Moscow, St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Kazan, Saratov, Khanty-Mansiysk, Elista, Omsk, Kemerovo, Ryazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Grozny and other cities. The conference was held with the informational support of the Russian Institute of Directors, NP "Elite Club of Corporate Conduct". -

Pan-Turkism and Geopolitics of China

PAN-TURKISM AND GEOPOLITICS OF CHINA David Babayan* Introduction People’s Republic of China (PRC) is currently one of the most powerful and dy- namically developing countries of the world. The economic development of the country is particularly impressive, as explicitly reflected in key economic indices, such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For instance, China’s GDP in 2007 was $3.43 trillion1, and in 2010 it already amounted to $6 trillion2. The foreign trade volume of the country also grows at astronomical rates. In 1982 it was $38.6 bil- lion3, in 2002 – $620.8 billion, and in 2010 totaled to almost $3 trillion4. According to Sha Zukang, United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs, China’s economic development is a sustained fast growth rare in modern world history5. Some experts even believe that while the first thirty years of China’s eco- nomic reforms program was about joining the world, the story of the next thirty years will be about how China reaches out and shapes the world6. Chinese analysts calculate the standing of nations by measuring “comprehensive national strength” of these nations7. This method relies on measuring four subsystems of a country’s national power: (1) material or hard power (natural resources, economy, science * Ph.D., History. 1 “China’s GDP grows 11.4 percent in 2007,” Xinhua, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2008-01/24/ content_7485388.htm, January 24, 2008. 2 Chen Yongrong, “China's economy expands faster in 2010, tightening fears grow”, Xinhua, http:// news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2011-01/20/c_13699250.htm, January 20, 2011. -

Наука Красноярья Krasnoyarsk Science

ISSN 2070-7568 НАУКА КРАСНОЯРЬЯ Журнал основан в 2011 г. №6(17) 2014 Главный редактор – Я.А. Максимов Выпускающий редактор – Н.А. Максимова Ответственный секретарь редакции – О.Л. Москаленко Технический редактор, администратор сайта – Ю.В. Бяков Компьютерная верстка – Л.И. Иосипенко KRASNOYARSK SCIENCE Founded in 2011 №6(17) 2014 Editor-in-Chief – Ya.А. Maksimov Deputy Editor-in-Chief – N.А. Maksimova Executive Secretary – O.L. Moskalenko Support Contact – Yu.V. Byakov Imposer – L.I. Iosipenko Красноярск, 2014 Научно-Инновационный Центр ---- 12+ Krasnoyarsk, 2014 Publishing House Science and Innovation Center Издательство «Научно-инновационный центр» НАУКА КРАСНОЯРЬЯ, №6(17), 2014, 268 с. Журнал зарегистрирован Енисейским управлением Федеральной службы по надзору в сфере связи, информационных технологий и массовых коммуникаций (свидетельство ПИ № ТУ 24-00430 от 10.08.2011) и Международным центром ISSN (ISSN 2070-7568). Журнал выходит шесть раз в год Статьи, поступающие в редакцию, рецензируются. За достоверность сведений, изложенных в статьях, ответственность несут авторы публикаций. Мнение ре- дакции может не совпадать с мнением авторов материалов. При перепечатке ссылка на журнал обязательна. Журнал представлен в полнотекстовом формате в НАУЧНОЙ ЭЛЕКТРОННОЙ БИБЛИОТЕКЕ в целях создания Российского индекса научного цитирования (РИНЦ). Адрес редакции, издателя и для корреспонденции: 660127, г. Красноярск, ул. 9 Мая, 5 к. 192 E-mail: [email protected] http://nkras.ru/nk/ Подписной индекс в каталоге «Пресса России» – 33298 Учредитель и издатель: Издательство ООО «Научно-инновационный центр» Publishing House Science and Innovation Center KRASNOYARSK SCIENCE, №6(17), 2014, 268 p. The edition is registered (certificate of registry PE № TU 24-00430) by the Federal Service of Intercommunication and Mass Media Control and by the International cen- ter ISSN (ISSN 2070-7568). -

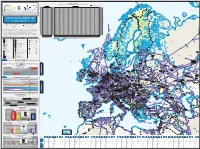

System Development Map 2019 / 2020 Presents Existing Infrastructure & Capacity from the Perspective of the Year 2020

7125/1-1 7124/3-1 SNØHVIT ASKELADD ALBATROSS 7122/6-1 7125/4-1 ALBATROSS S ASKELADD W GOLIAT 7128/4-1 Novaya Import & Transmission Capacity Zemlya 17 December 2020 (GWh/d) ALKE JAN MAYEN (Values submitted by TSO from Transparency Platform-the lowest value between the values submitted by cross border TSOs) Key DEg market area GASPOOL Den market area Net Connect Germany Barents Sea Import Capacities Cross-Border Capacities Hammerfest AZ DZ LNG LY NO RU TR AT BE BG CH CZ DEg DEn DK EE ES FI FR GR HR HU IE IT LT LU LV MD MK NL PL PT RO RS RU SE SI SK SM TR UA UK AT 0 AT 350 194 1.570 2.114 AT KILDIN N BE 477 488 965 BE 131 189 270 1.437 652 2.679 BE BG 577 577 BG 65 806 21 892 BG CH 0 CH 349 258 444 1.051 CH Pechora Sea CZ 0 CZ 2.306 400 2.706 CZ MURMAN DEg 511 2.973 3.484 DEg 129 335 34 330 932 1.760 DEg DEn 729 729 DEn 390 268 164 896 593 4 1.116 3.431 DEn MURMANSK DK 0 DK 101 23 124 DK GULYAYEV N PESCHANO-OZER EE 27 27 EE 10 168 10 EE PIRAZLOM Kolguyev POMOR ES 732 1.911 2.642 ES 165 80 245 ES Island Murmansk FI 220 220 FI 40 - FI FR 809 590 1.399 FR 850 100 609 224 1.783 FR GR 350 205 49 604 GR 118 118 GR BELUZEY HR 77 77 HR 77 54 131 HR Pomoriy SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT MAP HU 517 517 HU 153 49 50 129 517 381 HU Strait IE 0 IE 385 385 IE Kanin Peninsula IT 1.138 601 420 2.159 IT 1.150 640 291 22 2.103 IT TO TO LT 122 325 447 LT 65 65 LT 2019 / 2020 LU 0 LU 49 24 73 LU Kola Peninsula LV 63 63 LV 68 68 LV MD 0 MD 16 16 MD AASTA HANSTEEN Kandalaksha Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 MK 0 MK 20 20 MK 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM NL 418 963 1.381 NL 393 348 245 168 1.154 NL T +32 2 894 51 00 T +32 2 209 05 00 PL 158 1.336 1.494 PL 28 234 262 PL Twitter @ENTSOG Twitter @GIEBrussels PT 200 200 PT 144 144 PT [email protected] [email protected] RO 1.114 RO 148 77 RO www.entsog.eu www.gie.eu 1.114 225 RS 0 RS 174 142 316 RS The System Development Map 2019 / 2020 presents existing infrastructure & capacity from the perspective of the year 2020. -

Filoloji V2.Pdf

İmtiyaz Sahibi / Publisher • Yaşar Hız Genel Yayın Yönetmeniİmtiyaz Sahibi / Editor / Publisher in Chief • Yaşar• Eda AltunelHız Kapak &Genel İç Tasarım Yayın / YönetmeniCover & Interior / Editor Design in Chief • Gece • Eda Kitaplığı Altunel Kapak Editör& İç Tasarım / Edıtor / Cover• Doç. &Dr. Interior Yılmaz DKURT esign • Gece Kitaplığı BirinciEditör Basım // EdıtorFirst Edition • Prof. • Dr. © Aralık Serdar 2020 Öztürk ISBN • 978-625-7702-89-8 Birinci Basım / First Edition • © Aralık 2020 ISBN • 978-625-7319-31-7 © copyright Bu kitabın yayın hakkı Gece Kitaplığı’na aittir. Kaynak gösterilmeden alıntı yapılamaz, izin almadan hiçbir yolla çoğaltılamaz. The right to publish this book belongs to Gece Kitaplığı. Citation can not be shown without the source, reproduced in any way without permission. Gece Kitaplığı / Gece Publishing Türkiye Adres / Turkey Address: Kızılay Mah. Fevzi Çakmak 1. Sokak Ümit Apt. No: 22/A Çankaya / Ankara / TR Telefon / Phone: +90 312 384 80 40 web: www.gecekitapligi.com e-mail: [email protected] Baskı & Cilt / Printing & Volume Sertifika / Certificate No: 47083 Filoloji Alanında Teori ve Araştırmalar II EDİTÖR Doç. Dr. Yılmaz KURT İÇİNDEKİLER BÖLÜM 1 GOLAN TÜRKMENLERİNDE YIR SÖYLEME GELENEĞİ Mehmet EROL ......................................................................................1 BÖLÜM 2 ÇORY YAZITI’NDAN MİLLET MEKTEPLERİNE TÜRKÇE METİN YAZIMINDA KULLANILAN YAZI SİSTEMLERİ Rabia Şenay ŞIŞMAN ........................................................................21 BÖLÜM 3 AHMED KUDDÛSÎ DİVANI’NDA -

R U S S I a North Caucasus: Travel Advice

YeyskFOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH OFFICE BRIEFING NOTES ROSTOVSKAYA OBLAST’ Krasnyy Yar Ozero Astrakhan’ North Caucasus:Sal’sk Munych-Gudilo Travel Advice Elista ASTRAKHANSKAYA Primorsko-Akhtarsk Yashkul’ OBLAST’ Sea of RESPUBLIKA KALMYKIYA- Krasnogvardeyskoye KHAL’MG TANGCH Tikhoretsk Divnoye Azov KRASNODARSKIY KRAY Chograyskoye Vodokhranilishche Slavyansk-na-Kubani Kropotkin Lagan’ RUSSIASvetlograd Krasnodar Anapa Krymsk Blagodarnyy Tshchikskoye Armavir Stavropol’ Vodokhranihshche Kuma RESPUBLIKA Kuban’ STAVROPOL’SKIY KRAY ADYGEYA Novorossiysk Belorechensk Budennovsk Labinsk Nevinnomyssk Kizlyarskiy Maykop Zaliv Ostrov Tyuleniy Kochubey Cherkessk CASPIAN Tuapse Georgiyevsk Pyatigorsk Ostrov Chechen’ Kislovodsk Kizlyar Karachayevsk CHECHENSKAYA SEA KARACHAYEVO- Prokhladnyy Mozdok RESPUBLIKA (CHECHNYA) Sochi C CHERKESSKAYA RESPUBLIKA Nal’chik A Mount RESPUBLIKA Gudermes BLACK KABARDINO- INGUSHETIYA Groznyy El’brus Khasavyurt BALKARSKAYA Nazran Argun U RESPUBLIKA ABKHAZIA Ardon Magas SEA RESPUBLIKA Urus-Martan Makhachkala SEVERNAYA Vladikavkaz Kaspiysk COSETIYA-ALANIYA (NORTH OSSETIA) Buynaksk RESPUBLIKA A DAGESTAN International Boundary Khebda Autonomous Republic Boundary S Russian Federal Subject Boundary GEORGIA Derbent National Capital U Administrative Centre Other Town Advise against all travel Major Road AJARIA TBILISI S Rail Advise against all but essential travel 0 50miles See our travel advice before travelling 0 100kilometres TURKEY AZERBAIJAN FCO 279 Edition 1 (September 2011) Users should note that this map has been designed for briefing purposes only and it should not be used for determining the precise location of places or features. This map should not be considered an authority on the delimination of international boundaries or on the spelling of place and feature names. Maps produced for I&TD Information Management Depertment are not to be taken as necessarily representing the views of the UK government on boundaries or political status © Crown Copyright 2011. -

Association for Russian Centers for the Religious Studies the 5Th Congress of Russian Scholars of Religion November 26–28

Религиоведение. 2020. № 1 Religiovedenie [Study of Religion]. 2020. No. 1 DOI: 10.22250/2072-8662.2020.1.152-154 Association for Russian Centers for the Religious Studies The 5th Congress of Russian Scholars of Religion November 26–28, 2020 Saint Petersburg The State Museum of the History of Religion “RELIGION AND ATHEISM IN 21st CENTURY” Association for Russian Centers for the Religious Studies announces The 5th Congress of Russian Scholars of Religion. The 5th Congress continues the series of scholarly events being started at the 1st Congress (St-Petersburg, 2012) and afterwards kept up at the 2nd (St. Petersburg, 2014), the 3d (Vladimir, 2016) and the 4th (Blagoveshchensk, 2018) Congresses. The Congresses provides an interdisciplinary platform to discuss a great variety of problems, trends and phenomena in the field of contemporary Religious Studies, being the complex research area, methodologically based on humanities, social sciences and also, particularly during the last decades, on natural science. Previous Congresses took in participants from many cities of Russia, including Moscow, St. Petersburg, Arkhangelsk, Barnaul, Blagoveshchensk, Chita , Elista, Kazan, Khabarovsk, Krasnoyarsk, Murmansk, Nizhny Novgorod, Novgorod Veliky, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Oryol, Perm, Ryazan, Saratov, Sevastopol, Tambov, Tomsk, Tyumen, Ufa, Vladimir, Vladivostok, Volgograd, Voronezh, Yakutsk, Yaroslavl, Yekaterinburg. The scholars from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, China, Denmark, Germany, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Sweden, Ukraine and United Kingdom have traditionally contributed to the Congresses work. The Organizing Committee of the 5th Congress of Russian Scholars of Religion is happy to welcome all the scholars interested in Religious Studies from Russian Federation and other countries. Young scholars, postgraduate and graduate students are especially encouraged to contribute to the 5th Congress work. -

Major Hjalmar Front in Mongolia and Manchukuo, 1937-1938

ISSN 1226-4490 International Journal of Central Asian Studies Volume 2 1997 Editor in Chief Choi Han-Woo The International Association of Central Asian Studies Institute of Asian Culture and Development Major Hjalmar Front in Mongolia and Manchukuo, 1937- 1938 by Harry Halén Helsinki The name of Major Hjalmar Front is not commonly known in connection with Mongolia. In order to elucidate the Soviet activities in Mongolia in 1937-38 and Front's later career in the Japanese military service in Manchukuo, his account is here summarized. The summary is based on his reminiscences, published in Finnish in 1971 (Neuvostokomennuksella Siperiassa). This account might be of some interest for military historians and ethnographers. Hjalmar Front was born in 1900 in Sääksjärvi, Mäntsälä, in the southern part of Finland. He joined the Red Guard in 1918 in spite of his father's negative attitude. In fact, he was not so much ideologically interested, but simply eager to get a real gun instead of his risky home-made rifles. Later he became a famous marksman, taking innumerable prizes in Soviet Army competitions with machine gun, rifle and revolver. In the 1930's the battery under his command won the first prize among hundreds of batteries. He was also awarded the Order of the Red Flag for his role in the Russian Revolution and intervention wars. During the Finnish Civil War the young Red Guard fled in a boat and reached Petrograd at the end of April, 1918. He became a soldier and later an officer in the Bolshevik Army. Starting in 1920, he finished the middle school, a four year course at the International Military School and an additional three years at the Frunze Military Academy, which gave him the final touch to start a military career. -

REFERENCES 1. Ochir-Goryaeva M.A. 2008. Arkheologicheskie

REFERENCES 1. Ochir-Goryaeva M.A. 2008. Arkheologicheskie pamyatniki volgo-manychskikh stepey (svod pamyatnikov, issledovannykh na territorii Respubliki Kalmykiya v 1929–1997 gg.). [Archaeological monuments of the Volga-Manych steppes (the list of architectural monuments, explored on the territory of the Republic of Kalmykia in 1929–1997)]. Elista, Gerel Publishers: 298 p. (In Russian). 2. Zlatkin I.Ya. 1964. Istoriya Dzhungarskogo khanstva (1635–1758). [The history of the Dhungar khanate (1635–1758)]. Moscow, Nauka Publ.: 482 p. (In Russian). 3. Moiseev V.A. 1998. Rossiya i Dzhungarskoe khanstvo v XVIII veke (ocherk vneshnepoliticheskikh otnosheniy). [Russia and the Dzungar khanate in the 18th century (essay of foreign policy relations)]. Barnaul, Altai state University Publ.: 174 p. (In Russian). 4. Gurevich B.P. 1985. [The nature of the political status of the Dzungar khanate and its interpretation in the historiography of China]. In: IV Mezhdunarodnyy kongress mongolovedov. T. 1. [Proceedings of the IVth International Congress of Mongolists. Vol. I]. Ulanbaatar: 186–191. (In Russian and In Mongolian). 5. Tepkeev V.T. 2012. Kalmyki v severnom Prikaspii vo vtoroy treti XVII v.[Kalmyks in the North Caspian in the second third of the XVII century]. Elista, Dzhangar Publ.: 378 p. (In Russian). 6. Istoriya Kalmykii s drevneyshikh vremen do nashikh dney. V 3 t. [History of Kalmykia from ancient times to the present day. In three volumes. Vol. 3]. 2009. Elista, Gerel Publishing House: 848 p. (vol. 1); 840 p. (vol. 2); 752 p. (vol. 3). (In Russian). 7. Maksimov K.N. 2010. Velikaya Otechestvennaya voyna: Kalmykiya i kalmyki. 2-e izd., dop. -

Tibet Through the Eyes of a Buryat: Gombojab Tsybikov and His Tibetan Relations

ASIANetwork Exchange | Spring 2013 | volume 20 | 2 Tibet through the Eyes of a Buryat: Gombojab Tsybikov and his Tibetan relations Ihor Pidhainy Abstract: Gombojab Tsybikov (1873-1930), an ethnic Buryat from Russia, was a young scholar of oriental studies when he embarked on a scholarly expedition to Tibet. Under the sponsorship of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society, Tsybikov spent over a year in Lhasa (1900-1902), gathering materials and tak- ing photographs of the city and its environs, eventually introducing Tibet both academically and visually to the outside world. This paper examines the context of Tsybikov’s trip within the larger issues of scholarship, international politics, and modernization. In addition, it argues that Tsybikov was an example of a man caught between identities – an ethnic Buryat raised as a Buddhist, and a Russian citizen educated and patronized by that nation. He was, in a sense, the epitome of modern man. Keywords Tsybikov; Tibet; travel; Buryat; Russia; Buddhism; identity Gombojab Tsybikov’s (1873-1930) life and writings deal with the complex weavings of Ihor Pidhainy is Assistant identity encountered in the modern period.1 His faith and nationality positioned him as Professor of History at Marietta an “Asian”, while his education and employment within the Russian imperial framework College. His research focuses on the place of the individual in the marked him as “European.” His historical significance lies in his scholarly account of his complex of social, intellectual trip to Tibet. This paper examines Tsybikov’s relationship to Tibet, particularly in the period and political forces, with areas between 1899 and 1906, and considers how his position as an actor within the contexts of and periods of interest including empire, nation, and religious community made him an example of the new modern man.2 Ming dynasty China and Eura- sian interactions from the 18th The Buryats to 20th centuries. -

Phytonyms and Plant Knowledge in Sven Hedin's

GLIMPSES OF LOPTUQ FOLK BOTANY: PHYTONYMS AND PLANT KNOWLEDGE IN SVEN HEDIN’S HERBARIUM NOTES FROM THE LOWER TARIM RIVER AREA AS A SOURCE FOR ETHNOBIOLOGICAL RESEARCH Patrick Hällzon, Sabira Ståhlberg and Ingvar Svanberg Uppsala University This interdisciplinary study discusses the vernacular phytonyms and other ethnobiological aspects of vegetation in the Loptuq (Loplik) habitat on the Lower Tarim River. This small Turkic-speaking group lived as fisher-foragers in the Lopnor (Lop Lake) area in East Turkestan, now the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China. Information about this unique group, and especially the folk knowledge of plants in the area, is scant. In 1900, Swedish explorer Sven Hedin collected plant voucher specimens for the Swedish Natural History Museum in Stockholm. He noted local names on herbarium labels, thus providing modern researchers a rare glimpse into the Loptuq world. As the traditional way of life is already lost and the Loptuq language almost extinct, every trace of the former culture is of significance when trying to understand the peculiarities of human habitats and survival in arid areas. The ethnobiological analysis can further contribute to other fields, such as climate change, and define the place of the Loptuq on the linguistic and cultural map of Central Asia. LANGUAGE AND FOLK BOTANY Language reflects not only cultural reality and the way of life, but also human habitat and the physical environment.1 Rich biodiversity-based knowledge about the surrounding landscape and its biota (the living organisms of a specific region) has usually constituted an essential component of traditional and pre-industrial societies across the world (Lévi-Strauss 1962; Svanberg et al.