Finding the Nation in Sir Walter Scott's Waverley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

NATIONAL IDENTITY IN SCOTTISH AND SWISS CHILDRENIS AND YDUNG PEDPLEtS BODKS: A CDMPARATIVE STUDY by Christine Soldan Raid Submitted for the degree of Ph. D* University of Edinburgh July 1985 CP FOR OeOeRo i. TABLE OF CONTENTS PART0N[ paos Preface iv Declaration vi Abstract vii 1, Introduction 1 2, The Overall View 31 3, The Oral Heritage 61 4* The Literary Tradition 90 PARTTW0 S. Comparison of selected pairs of books from as near 1870 and 1970 as proved possible 120 A* Everyday Life S*R, Crock ttp Clan Kellyp Smithp Elder & Cc, (London, 1: 96), 442 pages Oohanna Spyrip Heidi (Gothat 1881 & 1883)9 edition usadq Haidis Lehr- und Wanderjahre and Heidi kann brauchan, was as gelernt hatq ill, Tomi. Ungerar# , Buchklubg Ex Libris (ZOrichp 1980)9 255 and 185 pages Mollie Hunterv A Sound of Chariatst Hamish Hamilton (Londong 197ý), 242 pages Fritz Brunner, Feliy, ill, Klaus Brunnerv Grall Fi7soli (ZGricýt=970). 175 pages Back Summaries 174 Translations into English of passages quoted 182 Notes for SA 189 B. Fantasy 192 George MacDonaldgat týe Back of the North Wind (Londant 1871)t ill* Arthur Hughesp Octopus Books Ltd. (Londong 1979)t 292 pages Onkel Augusta Geschichtenbuch. chosen and adited by Otto von Grayerzf with six pictures by the authorg Verlag von A. Vogel (Winterthurt 1922)p 371 pages ii* page Alison Fel 1# The Grey Dancer, Collins (Londong 1981)q 89 pages Franz Hohlerg Tschipog ill* by Arthur Loosli (Darmstadt und Neuwaid, 1978)9 edition used Fischer Taschenbuchverlagg (Frankfurt a M99 1981)p 142 pages Book Summaries 247 Translations into English of passages quoted 255 Notes for 58 266 " Historical Fiction 271 RA. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

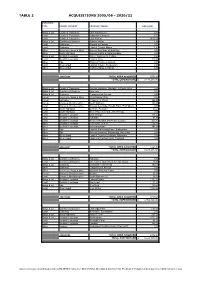

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

"I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Speth, Alana, ""I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624392. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-szar-c234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth Nicholson, Pennsylvania Bachelor of Arts, Smith College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Alana Speth Approved by the Committee L Committee Chair Pullen Professor James Whittenburg, History The College of William and Mary Professor LuAnn Homza, History The College of William and Mary • 7 i ^ i Assistant Professor Kathrin Levitan, History The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE The radical and complex changes that unfolded in the Scottish Highlands beginning in the middle of the eighteenth century have often been depicted as an example of mainstream British assimilation. -

Scottish Lowlands FD Strategic Plan 2007-2017

SCOTTISH LOWLANDS FOREST DISTRICT STRATEGIC PLAN 2007 – 2017 Scottish Lowlands Forest District Strategic Plan 2007 – 2017 1 Contents 1 Planning framework 3 2 Description of the District 8 3 Evaluation of the previous District Strategic Plan 15 4 Identification and analysis of issues 16 5 Response to the issues, implementation and monitoring 30 Appendices 1 Evaluation of achievements (1999-2006) under previous Strategic Plan 49 2 List of local plans and guidance 61 3 Scheduled ancient monuments, sites of special scientific interest and ancient woodland sites 63 4 District map 5 Standard maps 67-77 6 Key issues cross-referenced to SFS themes 78 Scottish Lowlands Forest District Strategic Plan 2007 – 2017 2 1 Planning framework 1.1 Introduction Forestry in Scotland is the responsibility of Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Government. Forestry Commission Scotland (FCS) acts as the Scottish Government’s Forestry Department. Forest Enterprise Scotland (FES) is an executive agency of FCS with the role of managing the national forest estate according to FCS policies. Scottish Lowlands Forest District is the part of FES with responsibility for management of the estate in central Scotland. The aim of this Plan is to describe how the District will deliver its part of the Scottish Forestry Strategy (SFS 2006), which is the forest policy of the Scottish Government. The strategy articulates a vision for forestry in Scotland, to be met by 2025. Scottish Forestry Strategy Vision By the second half of this century, people are benefiting widely from Scotland's trees, woodlands and forests, actively engaging with and looking after them for the use and enjoyment of generations to come. -

The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses August 2015 Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland Christine B. Anderson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Christine B., "Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland" (2015). Doctoral Dissertations. 342. https://doi.org/10.7275/6944753.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/342 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland A dissertation presented by CHRISTINE BROUGHTON ANDERSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Anthropology ©Copyright by Christine Broughton Anderson 2015 All Rights Reserved Uncovering and Recovering Cleared Galloway: The Lowland Clearances and Improvement in Scotland A Dissertation Presented By Christine Broughton Anderson Approved as to style and content by: H Martin Wobst, Chair Elizabeth Krause. Member Amy Gazin‐Schwartz, Member Robert Paynter, Member David Glassberg, Member Thomas Leatherman, Department Head, Anthropology DEDICATION To my parents. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with a sense of melancholy that I write my acknowledgements. Neither my mother nor my father will get to celebrate this accomplishment. -

NKU Academic Exchange in Leon, Spain

NKU Academic Exchange in Glasgow, Scotland http://www.world-guides.com Spend a semester or an academic year studying at Glasgow Caledonian University! A brief introduction… Office of Education Abroad (859) 572-6908 NKU Academic Exchanges The Office of Education Abroad offers academic exchanges as a study abroad option for independent and mature NKU students interested in a semester or year-long immersion experience in another country. The information in this packet is meant to provide an overview of the experience available through an academic exchange in Glasgow, Scotland. However, please keep in mind that this information, especially that regarding visa requirements, is subject to change. It is the responsibility of each NKU student participating in an exchange to take the initiative in the pre-departure process with regards to visa application, application to the exchange university, air travel arrangements, housing arrangements, and pre-approval of courses. Before and after departure for an academic exchange, the Office of Education Abroad will remain a resource and guide for participating exchange students. Scotland Scotland, located north of England, is one of the four constituent countries that make up the United Kingdom. Though kilts, haggis, bagpipes, whiskey, and sheep may come to mind when thinking of Scotland, the country certainly has much more to offer. The capital city Edinburgh, where the Medieval Old Town contrasts with the elegant Georgian New Town has an old-fashioned feel and unbeatable festivals. Glasgow is famous for high-end shopping, world-class museums, a wealth of Victorian architecture and bright, cheery inhabitants. Spectacular islands, beaches and the Highland countryside - a wild, beautiful tumble of raw mountain peaks and deep glassy lakes - complete the picture. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Scotland with the Greenville-Pitt County Chamber of Commerce

DISCOVER & EXPLORE SCOTLAND WITH THE GREENVILLE-PITT COUNTY CHAMBER OF COMMERCE Edinburgh, Scotland EARLY BIRD DISCOUNT BOOK & SAVE Click here to $3,399 PER PERSON $3,399 PER PERSON $3,099 PER PERSON $3,199 PER PERSON BOOK NOW if deposited by December 31st!* if deposited by February 14th!* Departing July 14, 2022 For more information, please contact Jackie Listecki at (252) 752-4101 HIGHLIGHTS: Edinburgh Castle and spend some and personal view of the course, leisure time exploring Calton we’d be happy to show you • Round trip scheduled airfare Hill and its unbeatable view of around following lunch.) Then, • Round trip transfers between Edinburgh before transferring to we’ll travel on to Inverness, the airports and hotels while overseas our hotel in Edinburgh. Few cities capital of the highlands. (B, L) • 6 nights hotel accommodation make such a strong impression Day 5: Inverness • 2 nights Edinburgh on the visitor as Edinburgh. After breakfast, enjoy a full day • 2 night Inverness Scotland’s capital is without a at leisure in Inverness where you • 2 night Glasgow doubt one of the most beautiful may wish to visit the Inverness • 8 meals: breakfast daily, 1 lunch and elegant cities in Europe. Castle and visit the Cathedral Join us for a Welcome Drink at and 1 dinner or meander alongside the loch. the hotel this evening before Or you have the option to join • Tours of: Edinburgh Castle, Rosslyn venturing out for dinner on your Chapel, Edinburgh, Inverness and us for a full day tour to the Isle own. of Skye with a visit to the Eileen Glasgow City Tours Day 3: Edinburgh • Time to visit: Dunfermline Abbey, Donan Castle; explore a 13th After breakfast, delve into Century Castle in the Highlands of Stirling Castle, St. -

Macg 1975Pilgrim Web.Pdf

-P L L eN cc J {!6 ''1 { N1 ( . ~ 11,t; . MACGRl!OOR BICENTDmIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND October 4-18, 197.5 sponsored by '!'he American Clan Gregor Society, Inc. HIS'lORICAL HIGHLIGHTS ABO ITINERARY by Dr. Charles G. Kurz and Claire MacGregor sessford Kurz , Art work by Sue S. Macgregor under direction of R. James Macgregor, Chairman MacGregor Bicentennial Pilgrimage booklets courtesy of W. William Struck, President Ambassador Travel Service Bethesda, Md • . _:.I ., (JUI lm{; OJ. >-. 8IaIYAt~~ ~~~~ " ~~f. ~ - ~ ~~.......... .,.; .... -~ - 5 ~Mll~~~. -....... r :I'~ ~--f--- ' ~ f 1 F £' A:t::~"r:: ~ 1I~ ~ IftlC.OW )yo X, 1.. 0 GLASGOw' FOREWORD '!hese notes were prepared with primary emphasis on MaoGregor and Magruder names and sites and their role in Soottish history. Secondary emphasis is on giving a broad soope of Soottish history from the Celtio past, inoluding some of the prominent names and plaoes that are "musts" in touring Sootland. '!he sequenoe follows the Pilgrimage itinerary developed by R. James Maogregor and SUe S. Maogregor. Tour schedule time will lim t , the number of visiting stops. Notes on many by-passed plaoes are information for enroute reading ani stimulation, of disoussion with your A.C.G.S. tour bus eaptain. ' As it is not possible to oompletely cover the span of Scottish history and romance, it is expected that MacGregor Pilgrims will supplement this material with souvenir books. However. these notes attempt to correct errors about the MaoGregors that many tour books include as romantic gloss. October 1975 C.G.K. HIGlU.IGHTS MACGREGOR BICmTENNIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND OCTOBER 4-18, 1975 Sunday, October 5, 1975 Prestwick Airport Gateway to the Scottish Lowlands, to Ayrshire and the country of Robert Burns. -

a - TASTE - of - SCOTLAND’S Foodie Trails

- a - TASTE - of - SCOTLAND’S Foodie Trails Your official guide to Scottish Food & Drink Trails and their surrounding areas Why not make a picnic of your favourite Scottish produce to enjoy? Looking out over East Lothian from the North Berwick Law. hat better way to get treat yourself to the decadent creations to know a country and of talented chocolatiers along Scotland’s its people and culture Chocolate Trail? Trust us when we say Wthan through its food? that their handmade delights are simply Eat and drink your way around Scotland’s a heaven on your palate – luscious and cities and countryside on a food and drink meltingly moreish! On both the Malt trail and experience many unexpected Whisky Trail and Scotland’s Whisky culinary treasures that will tantalise your Coast Trail you can peel back the taste buds and leave you craving more. curtain on the centuries-old art of whisky production on a visit to a distillery, while a Scotland’s abundant natural larder is pint or two of Scottish zesty and refreshing truly second to none and is renowned for ales from one of the breweries on the Real its unrivalled produce. From Aberdeen Ales Trail will quench your thirst after a Angus beef, Stornoway Black Pudding, day of exploring. And these are just some Arbroath Smokies and Shetland salmon of the ways you can satisfy your craving for and shellfish to Scottish whisky, ales, delicious local produce… scones, shortbread, and not to forget haggis, the range is as wide and diverse as Peppered with fascinating snippets of you can possibly imagine. -

Strategy for Lowland Raised Bog and Intermediate Bog on the National

Strategy for Lowland Raised Bog and Intermediate Bog on the National Forest Estate in Scotland 2012-2022 Lowland Raised Bogs Contents Contents......................................................................................................................... 2 Summary........................................................................................................................ 4 Lowland raised bogs and intermediate bogs on the national forest estate ...............4 Policy and strategic framework .........................................................................5 Existing conservation work on the national forest estate ......................................6 Prioritising sites..............................................................................................6 Planned work .................................................................................................8 Habitat importance and management history................................................................. 9 Extent and condition of the habitat on the national forest estate................................. 10 Number and type of sites on the national forest estate....................................... 11 Area of lowland raised bog by forest district ..................................................... 11 Area of intermediate bog by forest district........................................................ 12 Analysis of open bog and wooded areas........................................................... 12 Main land use categories for lowland