31 Chapter 2: the “Decline of Buddhism”: a New Archaeological Framework for Cultural Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf | 951.36 Kb

P a g e | 1 Operation Updates Report Pakistan: Monsoon Floods DREF n° MDRPK019 GLIDE n° FL-2020-000185-PAK Operation update n° 1; Date of issue: 6/10/2020 Timeframe covered by this update: 10/08/2020 – 07/09/2020 Operation start date: 10/08/2020 Operation timeframe: 6 months; End date: 28/02/2021 Funding requirements (CHF): DREF second allocation amount CHF 339,183 (Initial DREF CHF 259,466 - Total DREF budget CHF 598,649) N° of people being assisted: 96,250 (revised from the initially planned 68,250 people) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC Pakistan Country Office is actively involved in the coordination and is supporting Pakistan Red Crescent Society (PRCS) in this operation. In addition, PRCS is maintaining close liaison with other in-country Movement partners: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross (GRC), Norwegian Red Cross (NorCross) and Turkish Red Crescent Society (TRCS) – who are likely to support the National Society’s response. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), District Administration, United Nations (UN) and local NGOs. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: Another round of continuous heavy rains started in most part of the country on the week of 20 August 2020 until 3 September 2020 intermittently. The second round of torrential rains caused urban flooding in the Sindh province and flash flooding in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). New areas have been affected by the urban flooding including the districts of Malir, Karachi Central, Karachi West, Karachi East and Korangi (Sindh), and District Shangla, Swat and Charsadda in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. -

Pathan in Gilgit, Northern Pakistan

he boundary in between is indeed clearcut. But still, ambivalence remains ecause people can pass across the boundary. After giving an overview about Pathän in Gilgit and about relations etween Pathän and people of Gilgit, I will mainly focus on stereotypes setting he two groups apart from each other. Martin Sökefeld Gilgit Gilgit is the largest town of the high mountain area of Himalaya and STEREOTYPESAND BOUNDARIES: J{arakorum call.ed the "Northern Areas of Pakistan". Since 1947, the region has PATHÄN IN GILGIT, NORTHERN PAKISTAN governed by Pakistan. Gilgit is situated at a strategical position where . and routes from different directions meet. Mostly due to this position it been both center of power and target for conquest. For aproximately one a half centuries, Gilgit has been ruled by "foreign" powers, be they rulers "Pathän are dealing in heroin, weapons and everything. Because of them it neighbouring petty kingdoms Jike Yasin, a regional power Jike Kashmir, pened that every boy is carrying his own pistol. They think about nothing · · empire Iike Great Britain or a post-colonial state like Pakistan. about how to make money. They totally control the trade in Gilgit. They Gilgit's population is extremely diversified along various dimensions of all the trouble!" (Nusrat Wali, a young man from Gilgit) The people Jiving in Gilgit group themselves into innumerable delimited for example by religion, language, descent, regional be Introduction: Groups and boundaries and/or quasi-kinship. To take only one dimension of difference: fifteen mother tongues are spoken among roughly 40000 inhabitants. 1 Identity groups need boundaries. -

Accession of the States Had Been the Big Issue After the Division of Subcontinent Into Two Major Countries

Journal of Historical Studies Vol. II, No.I (January-June 2016) An Historical Overview of the Accession of Princely States Attiya Khanam The Women University, Multan Abstract The paper presents the historical overview of the accession of princely states. The British ruled India with two administrative systems, the princely states and British provinces. The states were ruled by native rulers who had entered into treaty with the British government. With the fall of Paramountacy, the states had to confirm their accession to one Constituent Assembly or the other. The paper discusses the position of states at the time of independence and unfolds the British, congress and Muslim league policies towards the accession of princely states. It further discloses the evil plans and scheming of British to save the congress interests as it considered the proposal of the cabinet Mission 1946 as ‘balkanisation of India’. Congress was deadly against the proposal of allowing states to opt for independence following the lapse of paramountancy. Congress adopted very aggressive policy and threatened the states for accession. Muslim league did not interfere with the internal affair of any sate and remained neutral. It respected the right of the states to decide their own future by their own choice. The paper documents the policies of these main parties and unveils the hidden motives of main actors. It also provides the historical and political details of those states acceded to Pakistan. 84 Attiya Khanam Key Words: Transfer of Power 1947, Accession of State to Pakistan, Partition of India, Princely States Introduction Accession of the states had been the big issue after the division of subcontinent into two major countries. -

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan)

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 The Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South is based on a network of partnerships with research institutions in the South and East, focusing on the analysis and mitigation of syndromes of global change and globalisation. Its sub-group named IP6 focuses on institutional change and livelihood strategies: State policies as well as other regional and international institutions – which are exposed to and embedded in national economies and processes of globalisation and global change – have an impact on local people's livelihood practices and strategies as well as on institutions developed by the people themselves. On the other hand, these institutionally shaped livelihood activities have an impact on livelihood outcomes and the sustainability of resource use. Understanding how the micro- and macro-levels of this institutional context interact is of vital importance for developing sustainable local natural resource management as well as supporting local livelihoods. For an update of IP6 activities see http://www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch (>Individual Projects > IP6) The IP6 Working Paper Series presents preliminary research emerging from IP6 for discussion and critical comment. Author Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. Village & Post Office Hazara, Tahsil Kabal, Swat–19201, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Distribution A Downloadable pdf version is availale at www.nccr- north-south.unibe.ch (-> publications) Cover Photo The Swat Valley with Mingawara, and Upper Swat in the background (photo Urs Geiser) All rights reserved with the author. -

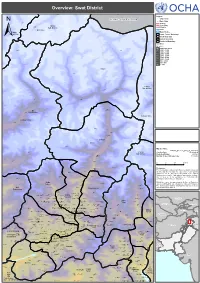

Swat District !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties. -

Social Welfare Program in the Former State of Swat (The Paradise Lost) Hafiz M

Social Welfare Program in the Former State of Swat (The Paradise Lost) Hafiz M. Yasin Abstract The Pakistanis in general and residents of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in particular are worried about the situation that has developed in Swat and other parts of Malakand division over the past few months. The lives, honour and properties of the inhabitants remained at risk and the innocent people of this region have turned refugees in their own homeland. The valley is now blazing; its educational and health centers blasted, its tourism and economy destroyed and its routes are no more safe for traveling. Swat was claimed to be a welfare state prior to its merger in1969. The State was famous for its prosperity and good governance. The literacy rate was much higher and health facilities far better than other parts of Pakistan. The driving force behind the success was obviously the devotion and efficiency of the rulers.This presentation draws upon a research report completed recently at IIIE, the International Islamic University Islamabad on the Fiscal System of the former State of Swat. A general public survey was conducted in three districts (Swat, Buner and Shangla) during early 2008 by approaching the common people and those who remained in the administration of the system some forty years back. Efforts were made to retrieve the old official record besides interviewing the prominent personalities. The present study gives an outline of the fiscal system and its nexus with the social sector development in Swat. The study focuses on the factors responsible for social security and alleviation of abject poverty, which in turn led to a general confidence of masses on the system, despite autocracy in the State. -

The Ignored Dardic Culture of Swat

Vol. 6(5), pp. 30-38, June, 2015 DOI: 10.5897/JLC2015.0308 Article Number: CBBA2D553114 Journal of Languages and Culture ISSN 2141-6540 Copyright © 2015 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JLC Review The ignored Dardic culture of Swat Zubair Torwali Bahrain Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Received 13 January, 2015; Accepted 28 March, 2015 The Greek historian Herodotus of the fifth century BC used the term “Dadikai” for people now known as Dards or Dardic. He placed the land between Kashmir and Afghanistan as Darada. “Darada” is the Sanskrit term used for the inhabitants of the region. In Pakistan the region is rarely called Dardistan or the people Dard, a Persian word derived from the Sanskrit “darada.” A linguistic and ethnic mystery shrouds the term Dardic. The termed was coined and used by colonial scholars. It was first used by the British orientalist Dr. Gottlieb Welhem Lietner (1840-1899). But no one in the region calls himself/herself Dard, as Dr. John Mock has noted in his paper, “Dards, Dardistan, and Dardic: an ethnographic, geographic and linguistic conundrum.” The Dard or Darada land in Pakistan includes Chitral, Swat, Dir, Indus Kohistan and Gilgit-Baltistan. The people spoke Dardic languages, one of the three groups belonging to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European family of languages. The Dardic languages include Dameli, Dumaki, Gawri (Kalami), Gawar-Bati, Gawro, Chilsoso, Glangali or Nangalami (Afghanistan), Kalasha, Kashmiri, Kashtawari (Kashmir) Khowar, Miaya (Indus Kohistani), Pashai (Nuristan, Kunar, Laghman, Kapisa Nangarhar in Afghanistan), Palula, Shina, Tirahi, Torwali and Wotapuri and a variety of minor languages. -

Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat

Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat Dr. SULTAN -I- ROME www.valleyswat.net Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat Courtesy: Sultan-I-Rome Copyright 2006. J.R.S.P. Vol. XXXXIII. No. 2, 2006 Download more papers and articles at ValleySwat. www.valleyswat.net 1 Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat Situated in the North-West Frontier Province of British India and later Pakistan, Swat State has the distinction of not being imposed by an imperial power or an individual but was founded in 1915 by jarga of a section of the right bank Swat Valley after doing away with the rule of the Nawab of Dir over their areas. The youngest of the Princely States of India and dependent upon British Indian Government and later Pakistan for currency, post and telegraph, and foreign affairs and later on electricity as well, Swat State was internally independent. It had "its own laws, its own system of justice, army, police and administration, budget and taxes,"1 and also its own flag with an emblem-of-a fort in golden green background. Swat State was probably the only governmental machine in the contemporary world which was run without superfluity of paper work, opined by Martin Moore." Originator of the administrative system of the State was Abdul Jabbar Shah, the first ruler of the State 0915-1917), which was modified, developed and refined by his successors at the seat of the State, namely Miangul Abdul Wadud who ruled from 1917 till 1949 and Miangul Jahanzeb who ruled from 1949 till the merger of the State in 1969. -

Development and the Battle for Swat Rabia Zafar

The Fletcher School Online Journal for issues related to Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization Spring 2011 Development and the Battle for Swat Rabia Zafar This paper examines the story of Swat through the In the early summer of 2009, world attention prism of human development, taking a narrow focused on Pakistan as Taliban militants gained a view of the ongoing unrest among Taliban foothold just 70 miles outside of the nation’s militants, the central government, and the capital, Islamabad, challenging the country’s disaffected people of the area. The paper begins nascent civilian government. The government by questioning the notion that the lack of responded with a strong show of military force, development and economic opportunities has pummeling the Swat Valley and surrounding been a significant impetus for religious extremism areas with tanks, heavy artillery, and helicopter and violence in Swat. It then evaluates other gunships. In the process, some 2 million people potential causes for the rise of Tehrikh-e-Taliban were internally displaced leaving Pakistan on the Pakistan (TTP) as a political force in the area. 2 brink of a large-scale humanitarian crisis. By late Next, the paper considers the Taliban’s strategy of June however, the military operation had started attacking symbols of modernity, such as girls’ yielding results and the government claimed that schools, infrastructure, and development-focused the Malakand Division, including Swat, had been NGOs, as a means to exert its control and cleared of the Taliban. 1 Most of the displaced establish a monopoly on governance. Finally, the civilians began returning to the area and paper concludes with an assessment of the post- international observers seemed satisfied that this conflict needs of the people of Swat, looking story had come to an end. -

How Bad Governance Led to Conflict: the Case of Swat, Pakistan

Munich Personal RePEc Archive How Bad Governance Led to Conflict: The Case of Swat, Pakistan Adnan, Rasool Center for Public Policy and Governance 15 November 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/35357/ MPRA Paper No. 35357, posted 12 Dec 2011 10:50 UTC How Bad Governance Led to Conflict: The Case of Swat Presented By, Adnan Rasool Final Thesis Adnan Rasool Pakistan has been facing a complex security situation along its Western borders for nearly a decade now. The volatile situation along the border with Afghanistan coupled with indigenous problems in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and the Provincially Administered Tribal Areas (PATA) in KP, have left the whole frontier region vulnerable to terrorist attacks as well as protracted armed conflict. During this time there has been a wave of Talibanization in FATA and PATA in KP, which has often ended up in military operations to flush out the miscreants. Over time, the attacks and operations have increased in frequency while the local Taliban (TTP) continue to wrest control of pockets of land in FATA and PATA in KP from where they continue to run their operation in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Over the last few years this wave of Talibanization has crossed over from the traditional border areas in to the more settled1 areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa such as Swat, Buner and Malakand. This trend reached its climax in 2009 when the Taliban inspired and allied, Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e- Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM) took over the Swat Valley and banished all Government functionaries operating there. -

The Dynamics of Public Perceptions and Climate Change in Swat Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

sustainability Article The Dynamics of Public Perceptions and Climate Change in Swat Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Muhammad Suleman Bacha 1 , Muhammad Muhammad 2,3 , Zeyneb Kılıç 4,* and Muhammad Nafees 1 1 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Peshawar, Peshawar 25000, Pakistan; [email protected] (M.S.B.); [email protected] (M.N.) 2 Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Peshawar, Peshawar 25000, Pakistan; [email protected] 3 Urban Policy and Planning Unit, Planning and Development Department, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Peshawar 25000, Pakistan 4 Department of Civil Engineering, Adiyaman University, Adiyaman 02040, Turkey * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +90-5538135664 Abstract: With rising temperatures, developing countries are exposed to the horrors of climate change more than ever. The poor infrastructure and low adaptation capabilities of these nations are the prime concern of current studies. Pakistan is vulnerable to climate-induced hazards including floods, droughts, water shortages, shifts in weather patterns, loss of biodiversity, melting of glaciers, and more in the coming years. For marginal societies dependent on natural resources, adaptation becomes a challenge and the utmost priority. Within the above context, this study was designed to fill the existing research gap concerning public knowledge of climate vulnerabilities and respective adaptation strategies in the northern Hindukush–Himalayan region of Pakistan. Using the stratified sampling technique, 25 union councils (wards) were selected from the nine tehsils (sub-districts) of Citation: Bacha, M.S.; Muhammad, M.; the study area. Using the quantitative method approach, structured questionnaires were employed Kılıç, Z.; Nafees, M. The Dynamics of to collect data from 396 respondents. -

Daboia Russelii (Reptilia: Squamata) in Remote Parts of Gujjar Village Miandam, Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan 1,2,*Wali Khan and 2Bashir Ahmad

Offcial journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(2) [General Section]: 212–216 (e206). Daboia russelii (Reptilia: Squamata) in remote parts of Gujjar Village Miandam, Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan 1,2,*Wali Khan and 2Bashir Ahmad 1Department of Zoology, University of Malakand lower Dir, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, PAKISTAN 2Department of Zoology, Hazara University, Mansehra, PAKISTAN Abstract.—Snakes are widely perceived with fear by the general public in Pakistan, and they are often killed on sight. The present study examines the range extension of Daboia russelii in remote parts of Gujjar village Miandam Swat, Pakistan. Seven snakes were collected, including three which were attacked and injured by the local men, and four others observed in the natural habitats in four localities: Karoo, Kalandori, Chharr, and Dhop, from June to September in both 2016 and 2017. Morphometric analysis, details of the coloration, and photographs of the snakes are provided. Russell’s Vipers were seen frequently in grasslands, cultivated felds, and areas near human residences. These snakes were mostly seen after sunset. This species has also been reported from other parts of Pakistan, but the present records represent a new locality. Keywords. Russell’s Viper, Viperidae, morphometric analysis, range extension, snake, venomous Citation: Khan W, Ahmad B. 2019. Daboia russelii (Reptilia: Squamata) in remote parts of Gujjar Village Miandam, Swat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 13(2) [General Section]: 212–216 (e206). Copyright: © 2019 Khan and Ahmad. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License [Attribu- tion 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/], which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.