Integrating Special-Status Territories Into National Political Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

08 July 2021, Is Enclosed at Annex A

Page 1 of3 MOST IMMEDIATE/BY FAX F.2 (E)/2020-NDMA (MW/ Press Release) Government of Pakistan Prime Minister's Office National Disaster Management Authority ISLAMABAD NDMA Dated: 08 July, 2021 Subject: Rain-wind / Thundershower predicted in upper & central parts from weekend (Monsoon likely to remain in active phase during 10-14 July 2021 concerned Fresh PMD Press Release dated 08 July 2021, is enclosed at Annex A. All measures to avoid any loss of life or are requested to ensure following precautionary property: FWO and a. Respective PDMAs to coordinate with concerned departments (NHA, obstruction. C&W) for restoration of roads in case of any blockage/ . Tourists/Visitors in the area be apprised about weather forecast C. Availability of staff of emergency services be ensured. Coordinate with relevant district and municipal administration to ensure d. mitigation measures for urban flooding and to secure or remove billboards/ hoardings in light of thunderstorm/ high winds the threat. e. Residents of landslide prone areas be apprised about In case of any eventuality, twice daily updates should be shared with NDMA. f. 2 Forwarded for information / necessary action, please. Lieutenant Colonel For Chainman NDMA (Muhammad Ala Ud Din) Tel: 051-9087874 Fax: 051 9205086 To Director General, PDMA Punjab Lahore Director General, PDMA Balochistan, Quetta Director General, PDMA Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Peshawar Director General, SDMA Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Muzaffarabad Director General, GBDMA Gilgit Baltistan, Gilgit General Manager, National Highways Authority -

Politics of Nawwab Gurmani

Politics of Accession in the Undivided India: A Case Study of Nawwab Mushtaq Gurmani’s Role in the Accession of the Bahawalpur State to Pakistan Pir Bukhsh Soomro ∗ Before analyzing the role of Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani in the affairs of Bahawalpur, it will be appropriate to briefly outline the origins of the state, one of the oldest in the region. After the death of Al-Mustansar Bi’llah, the caliph of Egypt, his descendants for four generations from Sultan Yasin to Shah Muzammil remained in Egypt. But Shah Muzammil’s son Sultan Ahmad II left the country between l366-70 in the reign of Abu al- Fath Mumtadid Bi’llah Abu Bakr, the sixth ‘Abbasid caliph of Egypt, 1 and came to Sind. 2 He was succeeded by his son, Abu Nasir, followed by Abu Qahir 3 and Amir Muhammad Channi. Channi was a very competent person. When Prince Murad Bakhsh, son of the Mughal emperor Akbar, came to Multan, 4 he appreciated his services, and awarded him the mansab of “Panj Hazari”5 and bestowed on him a large jagir . Channi was survived by his two sons, Muhammad Mahdi and Da’ud Khan. Mahdi died ∗ Lecturer in History, Government Post-Graduate College for Boys, Dera Ghazi Khan. 1 Punjab States Gazetteers , Vol. XXXVI, A. Bahawalpur State 1904 (Lahore: Civil Military Gazette, 1908), p.48. 2 Ibid . 3 Ibid . 4 Ibid ., p.49. 5 Ibid . 102 Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, Vol.XXV/2 (2004) after a short reign, and confusion and conflict followed. The two claimants to the jagir were Kalhora, son of Muhammad Mahdi Khan and Amir Da’ud Khan I. -

Deforestation in the Princely State of Dir on the North-West Frontier and the Imperial Strategy of British India

Central Asia Journal No. 86, Summer 2020 CONSERVATION OR IMPLICIT DESTRUCTION: DEFORESTATION IN THE PRINCELY STATE OF DIR ON THE NORTH-WEST FRONTIER AND THE IMPERIAL STRATEGY OF BRITISH INDIA Saeeda & Khalil ur Rehman Abstract The Czarist Empire during the nineteenth century emerged on the scene as a Eurasian colonial power challenging British supremacy, especially in Central Asia. The trans-continental Russian expansion and the ensuing influence were on the march as a result of the increase in the territory controlled by Imperial Russia. Inevitably, the Russian advances in the Caucasus and Central Asia were increasingly perceived by the British as a strategic threat to the interests of the British Indian Empire. These geo- political and geo-strategic developments enhanced the importance of Afghanistan in the British perception as a first line of defense against the advancing Russians and the threat of presumed invasion of British India. Moreover, a mix of these developments also had an impact on the British strategic perception that now viewed the defense of the North-West Frontier as a vital interest for the security of British India. The strategic imperative was to deter the Czarist Empire from having any direct contact with the conquered subjects, especially the North Indian Muslims. An operational expression of this policy gradually unfolded when the Princely State of Dir was loosely incorporated, but quite not settled, into the formal framework of the imperial structure of British India. The elements of this bilateral arrangement included the supply of arms and ammunition, subsidies and formal agreements regarding governance of the state. These agreements created enough time and space for the British to pursue colonial interests in Ph.D. -

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

Pdf | 951.36 Kb

P a g e | 1 Operation Updates Report Pakistan: Monsoon Floods DREF n° MDRPK019 GLIDE n° FL-2020-000185-PAK Operation update n° 1; Date of issue: 6/10/2020 Timeframe covered by this update: 10/08/2020 – 07/09/2020 Operation start date: 10/08/2020 Operation timeframe: 6 months; End date: 28/02/2021 Funding requirements (CHF): DREF second allocation amount CHF 339,183 (Initial DREF CHF 259,466 - Total DREF budget CHF 598,649) N° of people being assisted: 96,250 (revised from the initially planned 68,250 people) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC Pakistan Country Office is actively involved in the coordination and is supporting Pakistan Red Crescent Society (PRCS) in this operation. In addition, PRCS is maintaining close liaison with other in-country Movement partners: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross (GRC), Norwegian Red Cross (NorCross) and Turkish Red Crescent Society (TRCS) – who are likely to support the National Society’s response. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), District Administration, United Nations (UN) and local NGOs. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: Another round of continuous heavy rains started in most part of the country on the week of 20 August 2020 until 3 September 2020 intermittently. The second round of torrential rains caused urban flooding in the Sindh province and flash flooding in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). New areas have been affected by the urban flooding including the districts of Malir, Karachi Central, Karachi West, Karachi East and Korangi (Sindh), and District Shangla, Swat and Charsadda in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

Pathan in Gilgit, Northern Pakistan

he boundary in between is indeed clearcut. But still, ambivalence remains ecause people can pass across the boundary. After giving an overview about Pathän in Gilgit and about relations etween Pathän and people of Gilgit, I will mainly focus on stereotypes setting he two groups apart from each other. Martin Sökefeld Gilgit Gilgit is the largest town of the high mountain area of Himalaya and STEREOTYPESAND BOUNDARIES: J{arakorum call.ed the "Northern Areas of Pakistan". Since 1947, the region has PATHÄN IN GILGIT, NORTHERN PAKISTAN governed by Pakistan. Gilgit is situated at a strategical position where . and routes from different directions meet. Mostly due to this position it been both center of power and target for conquest. For aproximately one a half centuries, Gilgit has been ruled by "foreign" powers, be they rulers "Pathän are dealing in heroin, weapons and everything. Because of them it neighbouring petty kingdoms Jike Yasin, a regional power Jike Kashmir, pened that every boy is carrying his own pistol. They think about nothing · · empire Iike Great Britain or a post-colonial state like Pakistan. about how to make money. They totally control the trade in Gilgit. They Gilgit's population is extremely diversified along various dimensions of all the trouble!" (Nusrat Wali, a young man from Gilgit) The people Jiving in Gilgit group themselves into innumerable delimited for example by religion, language, descent, regional be Introduction: Groups and boundaries and/or quasi-kinship. To take only one dimension of difference: fifteen mother tongues are spoken among roughly 40000 inhabitants. 1 Identity groups need boundaries. -

Monthly Weather Report April 2019

Monthly Weather Report April 2019 Director General Pakistan Meteorological Department Prepared by: National Weather Forecasting Center Islamabad Contents SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 FIRST SPELL ................................................................................................................................... 3 SECOND SPELL ................................................................................................................................ 5 THIRD SPELL .................................................................................................................................. 7 FOURTH SPELL ............................................................................................................................... 9 ACCUMULATIVE RAINFALL ......................................................................................................... 11 FORECAST VALIDATION ............................................................................................................... 13 TEMPERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 14 DROUGHT CONDITION ................................................................................................................. -

Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations from 1978 to 2001: an Analysis

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 31, No. 2, July – December 2016, pp. 723 – 744 Pakistan-Afghanistan Relations from 1978 to 2001: An Analysis Khalid Manzoor Butt GC University, Lahore, Pakistan. Azhar Javed Siddqi Government Dayal Singh College, Lahore, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The entry of Soviet forces into Afghanistan in December 1979 was a watershed happening. The event brought about, inter alia, a qualitative change in Pakistan‟s relations with Afghanistan as well as balance of power in South Asia. The United States and its allies deciphered the Soviet move an attempt to expand its influence to areas vital for Washington‟s interests. America knitted an alliance of its friends to put freeze on Moscow‟s advance. Pakistan, as a frontline state, played a vital role in the eviction of the Soviet forces. This paved the way for broadening of traditional paradigm of Islamabad‟s Afghan policy. But after the Soviet military exit, Pakistan was unable to capitalize the situation to its advantage and consequently had to suffer from negative political and strategic implications. The implications are attributed to structural deficits in Pakistan‟s Afghan policy during the decade long stay of Red Army on Afghanistan‟s soil. Key Words: Durand Line, Pashtunistan, Saur Revolution, frontline state, structural deficits, expansionism, Jihad, strategic interests, Mujahideen, Pariah, Peshawar Accord Introduction Pakistan-Afghanistan relations date back to the partition of the subcontinent in August 1947. Their ties have been complex despite shared cultural, ethnic, religious and economic attributes. With the exception of the Taliban rule (1996- 2001) in Afghanistan, successive governments in Kabul have displayed varying degrees of dissatisfaction towards Islamabad. -

Accession of the States Had Been the Big Issue After the Division of Subcontinent Into Two Major Countries

Journal of Historical Studies Vol. II, No.I (January-June 2016) An Historical Overview of the Accession of Princely States Attiya Khanam The Women University, Multan Abstract The paper presents the historical overview of the accession of princely states. The British ruled India with two administrative systems, the princely states and British provinces. The states were ruled by native rulers who had entered into treaty with the British government. With the fall of Paramountacy, the states had to confirm their accession to one Constituent Assembly or the other. The paper discusses the position of states at the time of independence and unfolds the British, congress and Muslim league policies towards the accession of princely states. It further discloses the evil plans and scheming of British to save the congress interests as it considered the proposal of the cabinet Mission 1946 as ‘balkanisation of India’. Congress was deadly against the proposal of allowing states to opt for independence following the lapse of paramountancy. Congress adopted very aggressive policy and threatened the states for accession. Muslim league did not interfere with the internal affair of any sate and remained neutral. It respected the right of the states to decide their own future by their own choice. The paper documents the policies of these main parties and unveils the hidden motives of main actors. It also provides the historical and political details of those states acceded to Pakistan. 84 Attiya Khanam Key Words: Transfer of Power 1947, Accession of State to Pakistan, Partition of India, Princely States Introduction Accession of the states had been the big issue after the division of subcontinent into two major countries. -

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan)

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 The Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South is based on a network of partnerships with research institutions in the South and East, focusing on the analysis and mitigation of syndromes of global change and globalisation. Its sub-group named IP6 focuses on institutional change and livelihood strategies: State policies as well as other regional and international institutions – which are exposed to and embedded in national economies and processes of globalisation and global change – have an impact on local people's livelihood practices and strategies as well as on institutions developed by the people themselves. On the other hand, these institutionally shaped livelihood activities have an impact on livelihood outcomes and the sustainability of resource use. Understanding how the micro- and macro-levels of this institutional context interact is of vital importance for developing sustainable local natural resource management as well as supporting local livelihoods. For an update of IP6 activities see http://www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch (>Individual Projects > IP6) The IP6 Working Paper Series presents preliminary research emerging from IP6 for discussion and critical comment. Author Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. Village & Post Office Hazara, Tahsil Kabal, Swat–19201, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Distribution A Downloadable pdf version is availale at www.nccr- north-south.unibe.ch (-> publications) Cover Photo The Swat Valley with Mingawara, and Upper Swat in the background (photo Urs Geiser) All rights reserved with the author. -

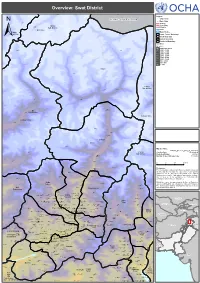

Swat District !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties.