The Changing Character of the Durand Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Election 2018 Update-Ii - Fafen General Election 2018

GENERAL ELECTION 2018 UPDATE-II - FAFEN GENERAL ELECTION 2018 Update-II April 01 – April 30, 2018 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) initiated its assessment of the political environment and implementation of election-related laws, rules and regulations in January 2018 as part of its multi-phase observation of General Election (GE) 2018. The purpose of the observation is to contribute to the evolution of an election process that is free, fair, transparent and accountable, in accordance with the requirements laid out in the Elections Act, 2017. Based on its observation, FAFEN produces periodic updates, information briefs and reports in an effort to provide objective, unbiased and evidence-based information about the quality of electoral and political processes to the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), political parties, media, civil society organizations and citizens. General Election 2018 Update-II is based on information gathered systematically in 130 districts by as many trained and non-partisan District Coordinators (DCs) through 560 interviews1 with representatives of 33 political parties and groups and 294 interviews with representative of 35 political parties and groups over delimitation process. The Update also includes the findings of observation of 559 political gatherings and 474 ECP’s centres set up for the display of preliminary electoral rolls. FAFEN also documented the formation of 99 political alliances, party-switching by political figures, and emerging alliances among ethnic, tribal and professional groups. In addition, the General Election 2018 Update-II comprises data gathered through systematic monitoring of 86 editions of 25 local, regional and national newspapers to report incidents of political and electoral violence, new development schemes and political advertisements during April 2018. -

Pashtunistan: Pakistan's Shifting Strategy

AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN PASHTUN ETHNIC GROUP PASHTUNISTAN: P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER May 2012 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? P ASHTUNISTAN : P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? The Pashtun tribes have yearned for a “tribal homeland” in a manner much like the Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. And as in those coun- tries, the creation of a new national entity would have a destabilizing impact on the countries from which territory would be drawn. In the case of Pashtunistan, the previous Afghan governments have used this desire for a national homeland as a political instrument against Pakistan. Here again, a border drawn by colonial authorities – the Durand Line – divided the world’s largest tribe, the Pashtuns, into two the complexity of separate nation-states, Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they compete with other ethnic groups for primacy. Afghanistan’s governments have not recog- nized the incorporation of many Pashtun areas into Pakistan, particularly Waziristan, and only Pakistan originally stood to lose territory through the creation of the new entity, Pashtunistan. This is the foundation of Pakistan’s policies toward Afghanistan and the reason Pakistan’s politicians and PASHTUNISTAN military developed a strategy intended to split the Pashtuns into opposing groups and have maintained this approach to the Pashtunistan problem for decades. Pakistan’s Pashtuns may be attempting to maneuver the whole country in an entirely new direction and in the process gain primacy within the country’s most powerful constituency, the military. -

Authoritarianism and Political Party Reforms in Pakistan

AUTHORITARIANISM AND POLITICAL PARTY REFORM IN PAKISTAN Asia Report N°102 – 28 September 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. PARTIES BEFORE MUSHARRAF............................................................................. 2 A. AFTER INDEPENDENCE..........................................................................................................2 B. THE FIRST MILITARY GOVERNMENT.....................................................................................3 C. CIVILIAN RULE AND MILITARY INTERVENTION.....................................................................4 D. DISTORTED DEMOCRACY......................................................................................................5 III. POLITICAL PARTIES UNDER MUSHARRAF ...................................................... 6 A. CIVILIAN ALLIES...................................................................................................................6 B. MANIPULATING SEATS..........................................................................................................7 C. SETTING THE STAGE .............................................................................................................8 IV. A PARTY OVERVIEW ............................................................................................... 11 A. THE MAINSTREAM:.............................................................................................................11 -

08 July 2021, Is Enclosed at Annex A

Page 1 of3 MOST IMMEDIATE/BY FAX F.2 (E)/2020-NDMA (MW/ Press Release) Government of Pakistan Prime Minister's Office National Disaster Management Authority ISLAMABAD NDMA Dated: 08 July, 2021 Subject: Rain-wind / Thundershower predicted in upper & central parts from weekend (Monsoon likely to remain in active phase during 10-14 July 2021 concerned Fresh PMD Press Release dated 08 July 2021, is enclosed at Annex A. All measures to avoid any loss of life or are requested to ensure following precautionary property: FWO and a. Respective PDMAs to coordinate with concerned departments (NHA, obstruction. C&W) for restoration of roads in case of any blockage/ . Tourists/Visitors in the area be apprised about weather forecast C. Availability of staff of emergency services be ensured. Coordinate with relevant district and municipal administration to ensure d. mitigation measures for urban flooding and to secure or remove billboards/ hoardings in light of thunderstorm/ high winds the threat. e. Residents of landslide prone areas be apprised about In case of any eventuality, twice daily updates should be shared with NDMA. f. 2 Forwarded for information / necessary action, please. Lieutenant Colonel For Chainman NDMA (Muhammad Ala Ud Din) Tel: 051-9087874 Fax: 051 9205086 To Director General, PDMA Punjab Lahore Director General, PDMA Balochistan, Quetta Director General, PDMA Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Peshawar Director General, SDMA Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Muzaffarabad Director General, GBDMA Gilgit Baltistan, Gilgit General Manager, National Highways Authority -

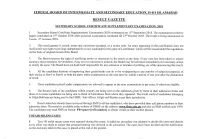

SSC-SUPPL-2018-RESULT.Pdf

FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 SALIENT FEATURES OF RESULT ALL AREAS G r a d e W i s e D i s t r i b u t i o n Pass Sts. / Grp. / Gender Enrolled Absent Appd. R.L. UFM Fail Pass A1 A B C D E %age G.P.A EX/PRIVATE CANDIDATES Male 6965 132 6833 16 5 3587 3241 97 112 230 1154 1585 56 47.43 1.28 Female 2161 47 2114 12 1 893 1220 73 63 117 625 335 7 57.71 1.78 1 SCIENCE Total : 9126 179 8947 28 6 4480 4461 170 175 347 1779 1920 63 49.86 1.40 Male 1086 39 1047 2 1 794 252 0 2 7 37 159 45 24.07 0.49 Female 1019 22 997 4 3 614 380 1 0 18 127 217 16 38.11 0.91 2 HUMANITIES Total : 2105 61 2044 6 4 1408 632 1 2 25 164 376 61 30.92 0.70 Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 Grand Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 2 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE GAZETTE Subjects EHE:I ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - I PST-II PAKISTAN STUDIES - II (HIC) AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I EHE:II ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - II U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I (HIC) F-N:I FOOD AND NUTRITION - I U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I (HIC) AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II F-N:II FOOD AND NUTRITION - II U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II (HIC) G-M:I MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - I U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II (HIC) ARB:I ARABIC - I G-M:II MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - II U-S URDU SALEES (IN LIEU OF URDU II) ARB:II ARABIC - II G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I WEL:I WELDING (ARC & GAS) - I BIO:I BIOLOGY - I G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I (HIC) WEL:II WELDING (ARC AND GAS) - II BIO:II BIOLOGY - II G-S:II GENERAL SCIENCE - II WWF:I WOOD WORKING AND FUR. -

Politics of Nawwab Gurmani

Politics of Accession in the Undivided India: A Case Study of Nawwab Mushtaq Gurmani’s Role in the Accession of the Bahawalpur State to Pakistan Pir Bukhsh Soomro ∗ Before analyzing the role of Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani in the affairs of Bahawalpur, it will be appropriate to briefly outline the origins of the state, one of the oldest in the region. After the death of Al-Mustansar Bi’llah, the caliph of Egypt, his descendants for four generations from Sultan Yasin to Shah Muzammil remained in Egypt. But Shah Muzammil’s son Sultan Ahmad II left the country between l366-70 in the reign of Abu al- Fath Mumtadid Bi’llah Abu Bakr, the sixth ‘Abbasid caliph of Egypt, 1 and came to Sind. 2 He was succeeded by his son, Abu Nasir, followed by Abu Qahir 3 and Amir Muhammad Channi. Channi was a very competent person. When Prince Murad Bakhsh, son of the Mughal emperor Akbar, came to Multan, 4 he appreciated his services, and awarded him the mansab of “Panj Hazari”5 and bestowed on him a large jagir . Channi was survived by his two sons, Muhammad Mahdi and Da’ud Khan. Mahdi died ∗ Lecturer in History, Government Post-Graduate College for Boys, Dera Ghazi Khan. 1 Punjab States Gazetteers , Vol. XXXVI, A. Bahawalpur State 1904 (Lahore: Civil Military Gazette, 1908), p.48. 2 Ibid . 3 Ibid . 4 Ibid ., p.49. 5 Ibid . 102 Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, Vol.XXV/2 (2004) after a short reign, and confusion and conflict followed. The two claimants to the jagir were Kalhora, son of Muhammad Mahdi Khan and Amir Da’ud Khan I. -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

Deforestation in the Princely State of Dir on the North-West Frontier and the Imperial Strategy of British India

Central Asia Journal No. 86, Summer 2020 CONSERVATION OR IMPLICIT DESTRUCTION: DEFORESTATION IN THE PRINCELY STATE OF DIR ON THE NORTH-WEST FRONTIER AND THE IMPERIAL STRATEGY OF BRITISH INDIA Saeeda & Khalil ur Rehman Abstract The Czarist Empire during the nineteenth century emerged on the scene as a Eurasian colonial power challenging British supremacy, especially in Central Asia. The trans-continental Russian expansion and the ensuing influence were on the march as a result of the increase in the territory controlled by Imperial Russia. Inevitably, the Russian advances in the Caucasus and Central Asia were increasingly perceived by the British as a strategic threat to the interests of the British Indian Empire. These geo- political and geo-strategic developments enhanced the importance of Afghanistan in the British perception as a first line of defense against the advancing Russians and the threat of presumed invasion of British India. Moreover, a mix of these developments also had an impact on the British strategic perception that now viewed the defense of the North-West Frontier as a vital interest for the security of British India. The strategic imperative was to deter the Czarist Empire from having any direct contact with the conquered subjects, especially the North Indian Muslims. An operational expression of this policy gradually unfolded when the Princely State of Dir was loosely incorporated, but quite not settled, into the formal framework of the imperial structure of British India. The elements of this bilateral arrangement included the supply of arms and ammunition, subsidies and formal agreements regarding governance of the state. These agreements created enough time and space for the British to pursue colonial interests in Ph.D. -

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

January 23, 2019 TDEA-FAFEN Briefs Election Support Group On

The Weekly Chronicle January 17 – January 23, 2019 TDEA-FAFEN Briefs Election Support Group on Women Voting Choices in GE-2018: During the reporting week, Trust for Democratic Education and Accountability – Free and Fair Election Network’s (TDEA-FAFEN) gave a briefing to the Election Support Group’s (ESG) members including representatives from funding agencies and other organizations working on elections in Pakistan regarding women voting choices during the General Election (GE) 2018. TDEA-FAFEN analyzed the polling station wise results’ data from 52,565 electoral areas to determine the women voting choices. Some of the major findings included: • Electoral choices of men and women are similar at 82% of analysed electoral areas. Choices of women deviate from men at 18% electoral areas. • Difference of voting choice of men and women is more prominent in Balochistan in comparison to other regions. These mostly favour Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), Awami National Party (ANP), Balochistan Awami Party (BAP) and Pashtunkhwa Milli Awami Party (PkMAP) in Balochistan. • In Punjab, more women preferred to vote for Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PML-N) and Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP), while men preferred to vote for PTI. • In almost every district of Sindh PPP remained the voting choice of women voters. • In Islamabad, PTI and PPPP won more male electoral areas than female. The PML-N’s victory in female electoral areas is three times greater than male electoral areas. USAID’s CVP Shares FAFEN Election Media Updates with Relevant Stakeholders: From January 17 to 23, 2019, Citizens’ Voice Project (CVP) shared five FAFEN election media updates with relevant stakeholders via email to update them on key electoral and political developments. -

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’S Posture Toward Afghanistan Since 2001

Old Habits, New Consequences Old Habits, New Khalid Homayun Consequences Nadiri Pakistan’s Posture toward Afghanistan since 2001 Since the terrorist at- tacks of September 11, 2001, Pakistan has pursued a seemingly incongruous course of action in Afghanistan. It has participated in the U.S. and interna- tional intervention in Afghanistan both by allying itself with the military cam- paign against the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida and by serving as the primary transit route for international military forces and matériel into Afghanistan.1 At the same time, the Pakistani security establishment has permitted much of the Afghan Taliban’s political leadership and many of its military command- ers to visit or reside in Pakistani urban centers. Why has Pakistan adopted this posture of Afghan Taliban accommodation despite its nominal participa- tion in the Afghanistan intervention and its public commitment to peace and stability in Afghanistan?2 This incongruence is all the more puzzling in light of the expansion of insurgent violence directed against Islamabad by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), a coalition of militant organizations that are independent of the Afghan Taliban but that nonetheless possess social and po- litical links with Afghan cadres of the Taliban movement. With violence against Pakistan growing increasingly indiscriminate and costly, it remains un- clear why Islamabad has opted to accommodate the Afghan Taliban through- out the post-2001 period. Despite a considerable body of academic and journalistic literature on Pakistan’s relationship with Afghanistan since 2001, the subject of Pakistani accommodation of the Afghan Taliban remains largely unaddressed. Much of the existing literature identiªes Pakistan’s security competition with India as the exclusive or predominant driver of Pakistani policy vis-à-vis the Afghan Khalid Homayun Nadiri is a Ph.D. -

Khushal Khan Khattak's Educational Philosophy

Khushal Khan Khattak’s Educational Philosophy Presented to: Department of Social Sciences Qurtuba University, Peshawar Campus Hayatabad, Peshawar In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Of Doctor of Philosophy in Education By Niaz Muhammad PhD Education, Research Scholar 2009 Qurtuba University of Science and Information Technology NWFP (Peshawar, Pakistan) In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. ii Copyrights Niaz Muhammad, 2009 No Part of this Document may be reprinted or re-produced in any means, with out prior permission in writing from the author of this document. iii CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL DOCTORAL DISSERTATION This is to certify that the Doctoral Dissertation of Mr.Niaz Muhammad Entitled: Khushal Khan Khattak’s Educational Philosophy has been examined and approved for the requirement of Doctor of Philosophy degree in Education (Supervisor & Dean of the Social Science) Signature…………………………………. Qurtuba University, Peshawar Prof. Dr.Muhammad Saleem (Co-Supervisor) Signature…………………………………. Center of Pashto Language & Literature, Prof. Dr. Parvaiz Mahjur University of Peshawar. Examiners: 1. Prof. Dr. Saeed Anwar Signature…………………………………. Chairman Department of Education Hazara University, External examiner, (Pakistan based) 2. Name. …………………………… Signature…………………………………. External examiner, (Foreign based) 3. Name. ………………………………… Signature…………………………………. External examiner, (Foreign based) iv ABSTRACT Khushal Khan Khattak passed away about three hundred and fifty years ago (1613–1688). He was a genius, a linguist, a man of foresight, a man of faith in Al- Mighty God, a man of peace and unity, a man of justice and equality, a man of love and humanity, and a man of wisdom and knowledge. He was a multidimensional person known to the world as moralist, a wise chieftain, a great religious scholar, a thinker and an ideal leader of the Pushtoons.