A Summary of the Climate of the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

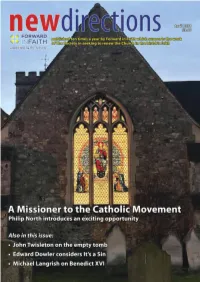

The Empty Tomb

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

The Theatricality of the Baroque City: M

THE THEATRICALITY OF THE BAROQUE CITY: M. D. PÖPPELMANN’S ZWINGER AT DRESDEN FOR AUGUSTUS THE STRONG OF SAXONNY PATRICK LYNCH TRINITY HALL CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY 1996 MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND PHILSOPHY OF ARCHITECTURE 1 CONTENTS: Acknowledgements. Preface. 1 Introduction to the topic of theatricality as an aspect of the baroque. i.i The problem of the term baroque. i.ii The problem of theatricality in the histories of baroque architecture: i.ii.a The theatricality of the Frame. i.ii.b The theatricality of Festival. ii The hermeneutics of theatricality: ii.i Hans-Georg Gadamer's formulation of play, symbol and festival as an interpretation of baroque theatricality. 2 The historical situation of the development of the Zwinger. i The European context. ii The local context. 3 The urban situation of the Zwinger. i Barockstadt Dresden. ii Barockstaat Sachsen. 4 A description of the development of the Zwinger. Conclusion: i Festival and the baroque city. A description of the Zwinger in use as it was inaugurated during the wedding celebrations of Augustus III and Marie Josepha von Habsburg, September 1719. ii Theatricality and the city. Bibliography. Illustrations: Volume 2 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: I would like to thank D.V. for supervising me in his inimitable way, and Dr. Christopher Padfield (and Trinity Hall) for generous financial support. This dissertation is dedicated to my family and friends, absent or otherwise and to C.M. in particular for first showing me the Zwinger and without whose care this document would not exist. PATRICK LYNCH 09/96 3 'Als ich nach der Augustusbrücke kam, die ich schon so gut aus Kupferstichen und Gemälden kannte, kam es mir vor, als ob ich schon früher einmal in Traum hier gewesen wäre.' (As I came upon the Augustusbrücke, which I knew so well from engravings and paintings, it seemed to me as if I had been here once before, in a dream.) Hans Christian Andersen 'This luscious and impeccable fruit of life Falls, it appears, of its own weight to earth. -

2010 Romanesque Confererence Abstracts

ROMANESQUE AND THE PAST ABSTRACTS John McNeill An Introduction to 11th and 12th-Century Attitudes to the Past One of the questions the conference is implicitly posing is whether there is a discernably Romanesque sense of the Past - an attitude or set of approaches to the past different to that of, say, the fourteenth century - or the fourth? And whether there is any consistency in the way this might be expressed - both across media - and across regions. By way of an introduction this paper will largely concentrate on architecture, and look at the ways in which spolia - material fragments of the past - were reused. It will suggest that the allusive capacity of spolia was important in certain areas of Europe in creating an architecture which attempted to emulate the architecture of Late Antiquity, particularly in the second half of the 11th century, though for the most part spolia was used for very specific and local reasons. It will conclude with a very brief consideration of emulation and architectural referentiality. Eric Fernie The Concept of the Romanesque The Romanesque style is one of the most loosely defined and controversial of art historical periods. The paper will assess the case against it and then that for it, concentrating on architecture and examining in particular when it is supposed to have begun, how it related to the political units of the time, and how it is used in conjunction with other period labels. The presentation concludes with an assessment of the origins of the Romanesque in a broad historical context. Richard Gem St Peter’s Basilica in Rome c.1024-1159: a model for emulation? The aim of this contribution is to evaluate the possible role of the ancient basilica of St Peter in Rome as a model for architectural design and for religious practice in Europe between the second quarter of the eleventh century and the middle of the twelfth (from Pope John XIX to Pope Hadrian IV). -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Download References File

TECNOLOGÍA NAVARRA DE NANOPRODUCTOS S.L. (TECNAN) THINK BIG, ACT NANO! REFERENCES RESTORATION AND CONSERVATION OF HERITAGE BUILDINGS TECNADIS PRODUCTS - REMARKABLE WORKS Metropolitan Cathedral Seville Cathedral Oviedo Cathedral (Panama City) (Sevilla - Spain) (Asturias - Spain) Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba La Almudena Cathedral Tui Cathedral Santander Cathedral (Córdoba - Spain) (Madrid - Spain) (Pontevedra - Spain) (Cantabria - Spain) Tarazona Cathedral Burgo de Osma Cathedral Pamplona Cathedral Segovia Cathedral (Zaragoza - Spain) (Soria - Spain) (Navarra - Spain) (Segovia - Spain) TECNADIS PRODUCTS - REMARKABLE WORKS Cologne Cathedral Pisa Cathedral Saint Bavon Cathedral Saint Esteban Cathedral (Italy) (Germany) (Ghent - Belgium) (Wien - Austria) (Bélgica) São João National Theatre Santo Domingo de la Calzada Cathedral Casa Milá – La Pedrera Viana Do Castelo Cathedral (Porto-Portugal) (La Rioja - Spain) (Barcelona - Spain) (Portugal) Buen Pastor Cathedral The Real Alcazar Casa Batlló Valencia Cathedral Museum (San Sebastián - Spain) (Sevilla - Spain) (Barcelona - Spain) (Valencia - Spain) TECNADIS PRODUCTS - REMARKABLE WORKS Bank of Spain Headquarters Santander Bank Headquarters National Library Parador of Leon (Madrid-Spain) (Santander - Spain) (Madrid - Spain) (León - Spain) ) Bank of Spain Building Spain Square Canalejas Complex Prado Museum (Málaga - Spain) (Sevilla - Spain) (Madrid - Spain) (Madrid - Spain) Royal Pavilion - Mª Luisa Park The old Seville Artillery Factory Astorga Episcopal Palace Catalunya Caixa Bank Headquarters -

Gothic Churches in Paris St Gervais Et St Protais Image Matching 3D Reconstruction to Understand the Vaults System Geometry

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W4, 2015 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25-27 February 2015, Avila, Spain GOTHIC CHURCHES IN PARIS ST GERVAIS ET ST PROTAIS IMAGE MATCHING 3D RECONSTRUCTION TO UNDERSTAND THE VAULTS SYSTEM GEOMETRY M.Capone a, , M. Campi b, R. Catuogno c a DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] b DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] c DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: Structure from Motion, Image Matching, 3D Modeling, Ribbed Vaults, Gothic Flamboyant, 3D reconstruction. ABSTRACT: This paper is part of a research about ribbed vaults systems in French Gothic Cathedrals. Our goal is to compare some different gothic cathedrals to understand the complex geometry of the ribbed vaults. The survey isn't the main objective but it is the way to verify the theoretical hypotheses about geometric configuration of the flamboyant churches in Paris. The survey method's choice generally depends on the goal; in this case we had to study many churches in a short time, so we chose 3D reconstruction method based on image dense stereo matching. This method allowed us to obtain the necessary information to our study without bringing special equipment, such as the laser scanner. The goal of this paper is to test image matching 3D reconstruction method in relation to some particular study cases and to show the benefits and the troubles. -

2008 Romanesque in the Sousa Valley.Pdf

ROMANESQUE IN THE SOUSA VALLEY ATLANTIC OCEAN Porto Sousa Valley PORTUGAL Lisbon S PA I N AFRICA FRANCE I TA LY MEDITERRANEAN SEA Index 13 Prefaces 31 Abbreviations 33 Chapter I – The Romanesque Architecture and the Scenery 35 Romanesque Architecture 39 The Romanesque in Portugal 45 The Romanesque in the Sousa Valley 53 Dynamics of the Artistic Heritage in the Modern Period 62 Territory and Landscape in the Sousa Valley in the 19th and 20th centuries 69 Chapter II – The Monuments of the Route of the Romanesque of the Sousa Valley 71 Church of Saint Peter of Abragão 73 1. The church in the Middle Ages 77 2. The church in the Modern Period 77 2.1. Architecture and space distribution 79 2.2. Gilding and painting 81 3. Restoration and conservation 83 Chronology 85 Church of Saint Mary of Airães 87 1. The church in the Middle Ages 91 2. The church in the Modern Period 95 3. Conservation and requalification 95 Chronology 97 Castle Tower of Aguiar de Sousa 103 Chronology 105 Church of the Savior of Aveleda 107 1. The church in the Middle Ages 111 2. The church in the Modern Period 112 2.1. Renovation in the 17th-18th centuries 115 2.2. Ceiling painting and the iconographic program 119 3. Restoration and conservation 119 Chronology 121 Vilela Bridge and Espindo Bridge 127 Church of Saint Genes of Boelhe 129 1. The church in the Middle Ages 134 2. The church in the Modern Period 138 3. Restoration and conservation 139 Chronology 141 Church of the Savior of Cabeça Santa 143 1. -

A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2018 A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Caitlin, "A Study of the Pantheon Through Time" (2018). Honors Theses. 1689. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1689 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of the Pantheon Through Time By Caitlin Williams * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Classics UNION COLLEGE June, 2018 ABSTRACT WILLIAMS, CAITLIN A Study of the Pantheon Through Time. Department of Classics, June, 2018. ADVISOR: Hans-Friedrich Mueller. I analyze the Pantheon, one of the most well-preserVed buildings from antiquity, through time. I start with Agrippa's Pantheon, the original Pantheon that is no longer standing, which was built in 27 or 25 BC. What did it look like originally under Augustus? Why was it built? We then shift to the Pantheon that stands today, Hadrian-Trajan's Pantheon, which was completed around AD 125-128, and represents an example of an architectural reVolution. Was it eVen a temple? We also look at the Pantheon's conversion to a church, which helps explain why it is so well preserVed. -

Map of La Rioja Haro Wine Festival

TRAVEL AROUND SPAIN SPAIN Contents Introduction.................................................................6 General information......................................................7 Transports.................................................................10 Accommodation..........................................................13 Food.........................................................................15 Culture......................................................................16 Region by region and places to visit..............................18 Andalusia........................................................19 Aragon............................................................22 Asturias..........................................................25 Balearic Islands...............................................28 Basque Country................................................31 Canary Islands.................................................34 Cantabria........................................................37 Castille-La Mancha...........................................40 Castille and León.............................................43 Catalonia........................................................46 Ceuta.............................................................49 Extremadura....................................................52 Galicia............................................................55 La Rioja..........................................................58 Madrid............................................................61 -

Are214b Building Structures Ib

ARE214B BUILDING STRUCTURES I B CHENG HO YIU REX 193401515 B.Sc. Yr2 May 27, 2020 LIST OF BUILDING STRUCTURES LECTURE 1 – INTRODUCTION Portuguese National Pavilion Expo 98, Lisbon, Portugal. 1998 | Alvaro Siza | Cecil Balmond (Engineer) A minimalistic pavilion with a wide-spanning curved concrete canopy, fastened between the roofs of two rolls of vertical columns by steel cables embedded inside the thin layers of concrete, HSBC Headquarters, Central, Hong Kong. 1985 | Norman Forster | Ove Arup & Partners (Engineer) High-rise office with exoskeleton structure with steel trusses and floors suspended by tension columns that supported by eight main clustered columns, each composed of 4 connected steel tubes, to create the large column free atrium. Pont du Gard Roman Aqueduct, Nimes, France. 40-60 AD Three tier semi-circular arch structure built with stone using only friction and gravity to transfer water in ancient times. Exchange House Office Building, Dockland, London. 1996 | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) The 10-story office building is supported by external steel frame structure that is hold up primarily by four parabolic arches, two internal and two external, to provide a column-free and flexible open office design. Statue of Liberty, New York City, USA. 1886 | Gustave Eiffel | Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (Sculptor) Structure ≠ Form | The neoclassical copper statue is sectioned into sheets of metal claddings which are attached to steel frames supported by four steel columns, is a gift from France to USA as a memorial to their independence. Greater Columbus Convention Center, Columbus, Ohio, USA. 1993 | Peter Eisenman Structure ≠ Form | The organic and irregular exterior is supported by convoluted structural frame that creates a strong juxtaposition with the convention centre’s large open interior. -

Selected Ancestors of the Chicago Rodger's

Selected Ancestors of the Chicago Rodger’s Volume I: Continental Ancestors Before Hastings David Anderson March 2016 Charlemagne’s Europe – 800 AD For additional information, please contact David Anderson at: [email protected] 508 409 8597 Stained glass window depicting Charles Martel at Strasbourg Cathedral. Pepin shown standing Pepin le Bref Baldwin II, Margrave of Flanders 2 Continental Ancestors Before Hastings Saints, nuns, bishops, brewers, dukes and even kings among them David Anderson March 12, 2016 Abstract Early on, our motivation for studying the ancestors of the Chicago Rodger’s was to determine if, according to rumor, they are descendants of any of the Scottish Earls of Bothwell. We relied mostly on two resources on the Internet: Ancestry.com and Scotlandspeople.gov.uk. We have been subscribers of both. Finding the ancestral lines connecting the Chicago Rodger’s to one or more of the Scottish Earls of Bothwell was the most time consuming and difficult undertaking in generating the results shown in a later book of this series of three books. It shouldn’t be very surprising that once we found Earls in Scotland we would also find Kings and Queens, which we did. The ancestral line that connects to the Earls of Bothwell goes through Helen Heath (1831-1902) who was the mother and/or grandmother of the Chicago Rodger’s She was the paternal grandmother of my grandfather, Alfred Heath Rodger. Within this Heath ancestral tree we found four lines of ancestry without any evident errors or ambiguities. Three of those four lines reach just one Earl of Bothwell, the 1st, and the fourth line reaches the 1st, 2nd and 3rd.