Flying Buttresses • Openings and Spans • Bar Tracery and Linear Elements • Large Scale Construction and Transmission of Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

The Digital Nature of Gothic

The Digital Nature of Gothic Lars Spuybroek Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic is inarguably the best-known book on Gothic architecture ever published; argumentative, persuasive, passionate, it’s a text influential enough to have empowered a whole movement, which Ruskin distanced himself from on more than one occasion. Strangely enough, given that the chapter we are speaking of is the most important in the second volume of The Stones of Venice, it has nothing to do with the Venetian Gothic at all. Rather, it discusses a northern Gothic with which Ruskin himself had an ambiguous relationship all his life, sometimes calling it the noblest form of Gothic, sometimes the lowest, depending on which detail, transept or portal he was looking at. These are some of the reasons why this chapter has so often been published separately in book form, becoming a mini-bible for all true believers, among them William Morris, who wrote the introduction for the book when he published it First Page of John Ruskin’s “The with his own Kelmscott Press. It is a precious little book, made with so much love and Nature of Gothic: a chapter of The Stones of Venice” (Kelmscott care that one hardly dares read it. Press, 1892). Like its theoretical number-one enemy, classicism, the Gothic has protagonists who write like partisans in an especially ferocious army. They are not your usual historians – the Gothic hasn’t been able to attract a significant number of the best historians; it has no Gombrich, Wölfflin or Wittkower, nobody of such caliber – but a series of hybrid and atypical historians such as Pugin and Worringer who have tried again and again, like Ruskin, to create a Gothic for the present, in whatever form: revivalist, expressionist, or, as in my case, digitalist, if that is a word. -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

Gothic Churches in Paris St Gervais Et St Protais Image Matching 3D Reconstruction to Understand the Vaults System Geometry

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W4, 2015 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, 25-27 February 2015, Avila, Spain GOTHIC CHURCHES IN PARIS ST GERVAIS ET ST PROTAIS IMAGE MATCHING 3D RECONSTRUCTION TO UNDERSTAND THE VAULTS SYSTEM GEOMETRY M.Capone a, , M. Campi b, R. Catuogno c a DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] b DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] c DiARC Dipartimento di Architettura Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, [email protected] Commission V, WG V/4 KEY WORDS: Structure from Motion, Image Matching, 3D Modeling, Ribbed Vaults, Gothic Flamboyant, 3D reconstruction. ABSTRACT: This paper is part of a research about ribbed vaults systems in French Gothic Cathedrals. Our goal is to compare some different gothic cathedrals to understand the complex geometry of the ribbed vaults. The survey isn't the main objective but it is the way to verify the theoretical hypotheses about geometric configuration of the flamboyant churches in Paris. The survey method's choice generally depends on the goal; in this case we had to study many churches in a short time, so we chose 3D reconstruction method based on image dense stereo matching. This method allowed us to obtain the necessary information to our study without bringing special equipment, such as the laser scanner. The goal of this paper is to test image matching 3D reconstruction method in relation to some particular study cases and to show the benefits and the troubles. -

Pentagons in Medieval Architecture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Építés – Építészettudomány 46 (3–4) 291–318 DOI: 10.1556/096.2018.008 PENTAGONS IN MEDIEVAL ARCHITECTURE KRISZTINA FEHÉR* – BALÁZS HALMOS** – BRIGITTA SZILÁGYI*** *PhD student. Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, BUTE K II. 82, Műegyetem rkp. 3, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] **PhD, assistant professor. Department of History of Architecture and Monument Preservation, BUTE K II. 82, Műegyetem rkp. 3, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] ***PhD, associate professor. Department of Geometry, BUTE H. II. 22, Egry József u. 1, H-1111 Budapest, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] Among regular polygons, the pentagon is considered to be barely used in medieval architectural compositions, due to its odd spatial appearance and difficult method of construction. The pentagon, representing the number five has a rich semantic role in Christian symbolism. Even though the proper way of construction was already invented in the Antiquity, there is no evidence of medieval architects having been aware of this knowledge. Contemporary sources only show approximative construction methods. In the Middle Ages the form has been used in architectural elements such as window traceries, towers and apses. As opposed to the general opinion supposing that this polygon has rarely been used, numerous examples bear record that its application can be considered as rather common. Our paper at- tempts to give an overview of the different methods architects could have used for regular pentagon construction during the Middle Ages, and the ways of applying the form. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE a History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016

AUSTRALIAN ROMANESQUE A History of Romanesque-Inspired Architecture in Australia by John W. East 2016 CONTENTS 1. Introduction . 1 2. The Romanesque Style . 4 3. Australian Romanesque: An Overview . 25 4. New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory . 52 5. Victoria . 92 6. Queensland . 122 7. Western Australia . 138 8. South Australia . 156 9. Tasmania . 170 Chapter 1: Introduction In Australia there are four Catholic cathedrals designed in the Romanesque style (Canberra, Newcastle, Port Pirie and Geraldton) and one Anglican cathedral (Parramatta). These buildings are significant in their local communities, but the numbers of people who visit them each year are minuscule when compared with the numbers visiting Australia's most famous Romanesque building, the large Sydney retail complex known as the Queen Victoria Building. God and Mammon, and the Romanesque serves them both. Do those who come to pray in the cathedrals, and those who come to shop in the galleries of the QVB, take much notice of the architecture? Probably not, and yet the Romanesque is a style of considerable character, with a history stretching back to Antiquity. It was never extensively used in Australia, but there are nonetheless hundreds of buildings in the Romanesque style still standing in Australia's towns and cities. Perhaps it is time to start looking more closely at these buildings? They will not disappoint. The heyday of the Australian Romanesque occurred in the fifty years between 1890 and 1940, and it was largely a brick-based style. As it happens, those years also marked the zenith of craft brickwork in Australia, because it was only in the late nineteenth century that Australia began to produce high-quality, durable bricks in a wide range of colours. -

Architectural Resourcesresources

CHAPTER2 ARCHITECTURALARCHITECTURAL RESOURCESRESOURCES Key features of historic resources should be preserved. This chapter presents a historic overview and identifies the key features of architectural styles found in San Jose: • Vernacular or National p. 17 • Italianate and Italianate Cottage p. 18 • Greek Revival p. 19 • Carpenter Gothic or Folk Victorian p. 19 • Queen Anne p. 20 • Stick p. 21 • Shingle p. 22 • Neoclassical p. 23 • Colonial Revival p. 24 • Dutch Colonial Revival p. 24 • Craftsman p. 25 • Bungalow p. 26 • Prairie p. 27 • Tudor Revival p. 28 • Mission Revival p. 28 • Spanish Eclectic or Spanish Colonial Revival or Mediterranean Revival p. 29 • Italian Renaissance p. 30 • Art Deco p. 30 • Art Moderne p. 31 • International p. 31 • Mid-Century Modern p. 32 Guide for Preserving San Jose Homes Chapter 2: Architectural Resources CHAPTER 2 ARCHITECTURALARCHITECTURAL RESOURCESRESOURCES Individual building features are important to the character of San Jose. The mass and scale, form, materials and architectural details of the buildings are the elements that distinguish one architectural style from another, or even older neighborhoods from newer developments. This chapter presents an overview of those important elements of the built environment which make up San Jose. This includes a brief history of development, as well as a summary of the different types and styles of architecture found in its neighborhoods. Brief History Vendome neighborhood, just to the northwest of the The settlement of the Santa Clara Valley by Euro- present-day Hensley Historic District. This original site Americans began in 1769 with an initial exploration was subjected to severe winter flooding during the first of the valley by Spanish explorers. -

Embodied Piety Sacrament Houses and Iconoclasm in the Sixteenth-Century Low Countries

bmgn - Low Countries Historical Review | Volume 131-1 (2016) | pp. 36-58 Embodied Piety Sacrament Houses and Iconoclasm in the Sixteenth-Century Low Countries anne-laure van bruaene On the eve of the Beeldenstorm, a great number of churches in the Low Countries had a sacrament house, a shrine for the Corpus Christi, often metres high. These monstrance-like tabernacles were nearly all destroyed by iconoclasts between 1566 and 1585. This essay discusses the dialectics between the construction and destruction of sacrament houses before and after the Beeldenstorm. It argues against a strict divide between material devotion and spiritual belief by highlighting the intertwining of Catholic and Calvinist embodied pieties. Fuelled by their opposing conceptions of the Eucharist, Catholic devotees and Protestant iconoclasts both engaged with sacrament houses and other expressions of the Corpus Christi devotion (processions, miracle cults et cetera) in a deliberate and intensely physical manner. Belichaamde vroomheid. Sacramentshuizen en iconoclasme in de zestiende-eeuwse Nederlanden Aan de vooravond van de Beeldenstorm stond in heel wat kerken in de Nederlanden een sacramentshuis, een vaak metershoge toren met het uiterlijk van een reusachtige monstrans, waarin het Corpus Christi werd tentoongesteld. Deze tabernakels werden haast allemaal vernield door iconoclasten tussen 1566 en 1585. Dit artikel bestudeert het samenspel tussen het optrekken en afbreken van sacramentshuizen voor en na de Beeldenstorm. De centrale stelling luidt dat we af moeten van een strikte scheiding tussen materiële devotie en spiritueel geloof. Zowel katholieken als calvinisten beleefden hun geloof op een belichaamde manier en hun handelingen waren steeds verweven. Vrome katholieke leken en protestantse beeldenstormers hadden sterk conflicterende ideeën over de eucharistie, maar juist daarom gingen ze op een heel bewuste en uiterst lichamelijke manier om met de sacramentshuizen en andere uitingen van sacramentsvroomheid zoals ommegangen en mirakelcultussen. -

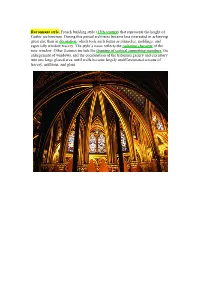

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral.