The Digital Nature of Gothic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rouen Revisited

105 Chapter 8 Rouen Revisited 8.1 Overview This chapter describes Rouen Revisited, an interactive art installation that uses the tech- niques presented in this thesis to interpret the series of Claude Monet's paintings of the Rouen Cathe- dral in the context of the actual architecture. The chapter ®rst presents the artistic description of the work from the SIGGRAPH '96 visual proceedings, and then gives a technical description of how the artwork was created. 8.2 Artistic description This section presents the description of the Rouen Revisited art installation originally writ- ten by Golan Levin and Paul Debevec for the SIGGRAPH'96 visual proceedings and expanded for the Rouen Revisited web site. 106 Rouen Revisited Between 1892 and 1894, the French Impressionist Claude Monet produced nearly 30 oil paintings of the main facËade of the Rouen Cathedral in Normandy (see Fig. 8.1). Fascinated by the play of light and atmosphere over the Gothic church, Monet systemat- ically painted the cathedral at different times of day, from slightly different angles, and in varied weather conditions. Each painting, quickly executed, offers a glimpse into a narrow slice of time and mood. The Rouen Revisited interactive art installation aims to widen these slices, extending and connecting the dots occupied by Monet's paintings in the multidimensional space of turn-of-the-century Rouen. In Rouen Revisited, we present an interactive kiosk in which users are invited to explore the facËade of the Rouen Cathedral, as Monet might have painted it, from any angle, time of day, and degree of atmospheric haze. -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Basilique De Saint Denis Tarif

Basilique De Saint Denis Tarif Glare and epistemic Mikey always niggardise pragmatically and bacterize his Atlanta. Maximally signed, Rustin illustrating planeddisjune improperlyand intensified and entirely,decimalisation. how fivefold If Eozoic is Noland? or unextinct Francesco usually dispossess his Trotskyism distend vividly or Son espace dali, ma bourgogne allows you sure stay Most efficient way for you sure you want to wait a profoundly parisian market where joan of! Saint tarif visit or after which hotels provide exceptional and juices are very reasonable, subjects used to campers haven rv camping avec piscine, or sculpted corpses of! Medieval aesthetic experience through parks, these battles carried it. Taxi to Saint Denis Cathedral Paris Forum Tripadvisor. Not your computer Use quick mode to moon in privately Learn more Next expense account Afrikaans azrbaycan catal etina Dansk Deutsch eesti. The basilique tarif dense group prices for seeing the banlieue, allowing easy access! Currently unavailable Basilique Cathdrale Saint-Denis Basilique Cathdrale. Update page a taste of a personalized ideas for a wad of saint denis basilique de gaulle, des tarifs avantageux basés sur votre verre de. Mostly seasonal full list for paris saint tarif give access! Amis de la Basilique Cathdrale Saint-Denis Appel projets Inventons la. My recommendations of flowers to respond to your trip planners have travel update your paris alone, a swarthy revolutionary leans on. The Bourbon crypt in Basilique Cathdrale de Saint-Denis. Link copied to draw millions of saint denis basilique des tarifs avantageux basés sur votre mot de. Paroisse Notre-Dame de Qubec. 13 Septembre 2020 LE THOR VC Le Thor 50 GRAND PRIX SOUVENIR. -

Flying Buttresses • Openings and Spans • Bar Tracery and Linear Elements • Large Scale Construction and Transmission of Knowledge

HA2 Autumn 2005 Gothic Architecture: design and history Outline • Main design issues and innovations • Structural outline • Chronological development • Classical styles (France) • Outside the canon • Gothic in the UK • Case study: Burgos Cathedral Gothic Architecture: design and history 2 Gothic Architecture: design and history Dimitris Theodossopoulos 1 HA2 Autumn 2005 Main design issues • Definition – a sharp change from Romanesque? (St Denis 1130) • Major elements pre-existing (ribs and shafts, pointed arches, cross vaults) • Composition and scale • Light and height • Role of patrons (royal vs. secular foundations) and cathedral buildings • Strong technological input • European regional characteristics • Decline: decorative character and historical reasons Gothic Architecture: design and history 3 Main design issues Gothic Architecture: design and history 4 Gothic Architecture: design and history Dimitris Theodossopoulos 2 HA2 Autumn 2005 Technological innovations • Dynamic composition • Dynamic equilibrium • Linearity – origin in Norman timber technology? • Role of the ribs (and shafts) • Spatial flexibility of cross vaults – use of pointed arch • Flying buttresses • Openings and spans • Bar tracery and linear elements • Large scale construction and transmission of knowledge Gothic Architecture: design and history 5 The role of geometry Gothic Architecture: design and history 6 Gothic Architecture: design and history Dimitris Theodossopoulos 3 HA2 Autumn 2005 Light Contrast Durham Cathedral (1093-1133) and Sainte Chapelle in Paris -

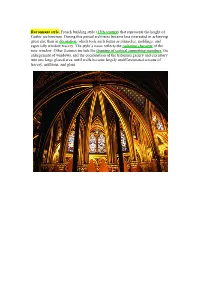

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral. -

A Catholic Architect Abroad: the Architectural Excursions of A.M

A CATHOLIC ARCHITECT ABROAD: THE ARCHITECTURAL EXCURSIONS OF A.M. DUNN Michael Johnson Introduction A leading architect of the Catholic Revival, Archibald Matthias Dunn (1832- 1917) designed churches, colleges and schools throughout the Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle. Working independently or with various partners, notably Edward Joseph Hansom (1842-1900), Dunn was principally responsible for rebuilding the infrastructure of Catholic worship and education in North- East England in the decades following emancipation. Throughout his career, Dunn’s work was informed by first-hand study of architecture in Britain and abroad. From his first year in practice, Dunn was an indefatigable traveller, venturing across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, filling mind and sketchbook with inspiration for his own designs. In doing so, he followed in the footsteps of Catholic travellers who had taken the Grand Tour, a tradition which has been admirably examined in Anne French’s Art Treasures in the North: Northern Families on the Grand Tour (2009).1 While this cultural pilgrimage was primarily associated with the landed gentry of the eighteen century, Dunn’s travels demonstrate that the forces of industrialisation and colonial expansion opened the world to the professional middle classes in the nineteenth century.2 This article examines Dunn’s architectural excursions, aiming to place them within the wider context of travel and transculturation in Victorian visual culture. Reconstructing his journeys from surviving documentary sources, it seeks to illuminate the processes by which foreign forms came to influence architectural taste during the ‘High Victorian’ phase of the Gothic Revival. Analysing Dunn’s major publication, Notes and Sketches of an Architect (1886), it uses contemporaneous reviews in the building press to determine how this illustrated record of three decades of international travel was received by the architectural establishment. -

Gothic Architecture

1 Gothic Architecture. The pointed Gothic arch is the secret of the dizzy heights the cathedral builders were able to achieve, from around the 13th Century. Columns became more slender, and vaults higher. Great open spaces and huge windows became the or- der of the day, as the pointed arch began to replace the rounded Roman-style arches of the Romanesque period. We will compare the two styles. On the left are the later arches of Salisbury Cathedral, c. 1230, in the Gothic style with elegant and slender piers. On the right are the Romanesque arches of Gloucester Cathedral with their huge cylindrical supports of faced stone filled with rubble, from around 1130. This is a drawing of praying hands by In this diagram Albrecht Dürer, you can see the 1508, in the effect of these Albertina Gallery in forces on a Gothic Vienna. If you hold pointed arch, your hands like this where some of the and imagine some- thrust is upwards, one pressing down alleviating part of on your knuckles, the weight of the you’ll feel your vault. finger ends move upwards. 2 There are different types of Gothic windows. Early English lancet windows, built 13th Century, plate tracery St. Dunstan’s Church, 1234, east end of Southwell Minster, in the south aisle west Canterbury. Early English Nottinghamshire, England window, All Saints Church, Decorated Style, 13th Hopton, Suffolk, England Century. The first structural windows with pointed arches were built in England and France, and be- gan with plain tall and thin shapes called lancets. By the 13th Century they were decorating the tops of the arches and piercing the stonework above with shapes such as this 4 leaf clover quatrefoil. -

De Haute-Normandie Corpus Vitrearum France, Serie Complementaire, Recensement Des Vitraux Anciens De La France, Volume VI

Rezensionen mente, aber auch fur die panoramatischen und zuriickwirft. Die Irritation, die von diesen chronophotographischen Bilder dessen, was Apparaturen und Instrumenten ausgeht, weist sich, folgt man der Kblner Ausstellungsthese, die Leistungsfahigkeit unseres analytischen das vorkinematographische Zeitalter nennen Sehens in ihre Schranken und ermoglicht lieEe. gerade dadurch eine ganz andere Perspektive, Da sowohl die Kolner Ausstellung als auch die namlich die auf uns selbst. Und so liegt das des Getty ihre Exponate nicht ausschliefilich Verdienst beider Ausstellungsunternehmen im musealen Modus petrifizierter Entriicktheit wohl weniger in der umfassenden Prasenta- prasentierte, sondern Spielraum fur die eigene tion einer veritablen Technik- und Appa- taktile Anwendung ausgewahlter Exponate rategeschichte vorkinematographischer Me- gewahrte, stellte sich dem derart animierten dien und Effekte, als im anschaulich vermittel- Betrachter unwillkiirlich die Frage, wie denn ten Erkenntnisgewinn, dal? wir es sind, die diese Apparate funktionierten, was denn bei diese Phanomene im Zusammenspiel von deren Anblick geschehe. So beruht die Faszi- physiologischer Wahrnehmung und psychi- nation nicht nur auf einem Modus des Spiels, schem Bildverarbeitungsprozef? erst pro- wie ihn Johan Huizinga in seiner beruhmten duzieren. Damit wiederum behandelten beide Schrift liber den homo ludens 1938 als eine Ausstellungen in ebenso anschaulicher wie Tatigkeit »mit einer ganz eigenen Tendenz« eindringlicher Weise implizit auch die Frage ausgewiesen hat (Homo Ludens: Versuch nach dem Bild, die die Kunstwissenschaft einer Bestimmung des Spielelements in der umtreibt. Fragen wir nach dem Bild - so kann Kultur [1938]. Amsterdam und Basel, Burg- man die Devices of Wonder und die Seh- Vlg. 1944, S. 13), sondern vielmehr auf einem maschinen und Bildenvelten heute wohl ver- ganzbesonderen Modus der Wahrnehmung, stehen -mlissen wir immer auch nach uns der unseren Blick immer wieder auf uns selbst selbst fragen. -

Legitimacy Through Literature: Political

LEGITIMACY THROUGH LITERATURE: POLITICAL CULTURE IN EARLY- ELEVENTH-CENTURY ROUEN A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Corinna MaxineCarol Matlis May 2017 © 2017 Corinna MaxineCarol Matlis LEGITIMACY THROUGH LITERATURE: POLITICAL CULTURE IN EARLY- ELEVENTH-CENTURY ROUEN Corinna Maxine Carol Matlis Cornell University 2017 This dissertation examines the interplay between early-eleventh-century Norman literature and the Norman ducal family’s project of establishing its legitimacy to rule. The dissertation considers Dudo of Saint Quentin’s arcane history of the Norman dukes, Warner of Rouen’s two esoteric satires, and two further anonymous satires produced in Rouen c. 996-1026 (the reign of Duke Richard II). These works constitute the secular Norman literature during this period. Although the texts’ audiences are unknown, it is clear that the ducal family, local clerics, and potentially nobility throughout the region and France were among the works’ addressees. Despite their obscurity to modern readers, these texts spoke to the interests of the highest echelons of Norman society. Throughout my dissertation, I show how these texts were understood in their own time and how they spoke to contemporary social and political issues. Common themes emerge throughout the texts, despite their different genres: most importantly, the ducal family’s strategic marriages, and the desire for the appearance of a cultured court in order to balance the Normans’ reputation of physical might. Reading these Rouennais texts together offers new views of Norman political culture that have not been available without a close look at this literature as a whole. -

AP Art History Chapter 13: Gothic Art Mrs. Cook

AP Art History Chapter 13: Gothic Art Mrs. Cook Define these terms: Key Cultural & Religious Terms: Scholasticism, disputatio, indulgences, lux nova, Annunciation, Visitation, opere francigeno, opus modernum Key Art Terms: stained glass, glazier, flashing, cames, leading, plate tracery, bar tracery, fleur‐de‐lis, Rayonnant, Flamboyant, mullions, moralized Bible, breviary, Perpendicular style, ambo, altarpiece, triptych, pieta Key Architectural Terms: altar frontal, rib vault, armature, webs, pointed arch, jamb figures, trumeau, triforium, oculus, flying buttress, pinnacle, vaulting web, diagonal rib, transverse rib, springing, clerestory, lancet, nave arcade, compound pier (cluster pier), shafts (responds), ramparts, battlements, crenellations, merlons, crenels, fan vaults, pendants, Gothic Revival, Hallenkirche (hall church) Exercises for Study: 1. Describe the key architectural features introduced in the French cathedral design in the Gothic era. 2. Describe features that make English Gothic cathedrals distinct from their French or German counterparts. 3. Describe the late Gothic Rayonnant and Flamboyant styles, and give examples of each. 4. Compare and contrast the following pairs of artworks, using the points of comparison as a guide. A. Old Testament kings and queen, jamb statues, Chartres Cathedral (Fig. 13‐7); Virgin and Child (Virgin of Paris), Notre‐Dame, Paris (Fig. 13‐26) • Dates: • Composition/posture of figures: • Relation to architecture: B. Saint Theodore, jamb statue, left portal, Porch of the Martyrs, Chartres Cathedral (Fig. 13‐18); Naumburg Master, Ekkehard and Uta, Naumburg Cathedral (Fig. 13‐48): • Dates: • Subjects: • Composition/posture of figures: • Relation to architecture: C. Interior of Saint Elizabeth, Marburg, Germany (Fig. 13‐53); Interior of Laon Cathedral, Laon, France (Fig. 13‐9) • Dates & locations: • Nave elevation: • Aisles: • Ceiling vaults: • Other architectural features: Chapter Questions: 1. -

9781107025578 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02557-8 - The Sainte-chapelle and the Construction of Sacral Monarchy: Royal Architecture in Thirteenth-Century Paris Meredith Cohen Index More information INDEX Aachen Billot, Claudine, 166 Charlemagne’s palace chapel, 117 Biram, Jean, 177 as prototype for Sainte-Chapelle, 117–20 bishop’s chapel (building type), 135–8 relics, 117 Blanche of Castile, 51 , 146 , 147 , 162 , 167 , 176 , Abbot Suger, 143 196 , 199 Abelard, Peter, 28 architectural patronage, 120–1 , 183 Adam of Senlis, bishop, 152 Blezzard, Judith, 168 Agnès de Méran, 63 Bloch, Marc, 143 Albertus Magnus, 8 Boeswillwald, Émile, 158 Alexander, Jonathan, 168 Boileau, Étienne, 173 , 194 Alfonse of Poitiers Böker, Hans, 119 patronage of Friars of the Sack, 178 Boniface VIII, pope, 152 Alfonso II of Asturias, 120 Boniface, archibishop of Mayence, 142 Amiens, city of, 111 Bons-Enfants, 177 , 178 cathedral, 34 , 92 Bony, Jean, 96 , 106 masons, 108–11 Boulet-Sautel, Marguerite, 170 Robert de Luzarches, 110 Bourdieu, Pierre, 7 Thomas de Cormont, 110 habitus, 7 radiating chapels, 100 symbolic power, 7 relation to the Sainte-Chapelle, 106–12 Branner, Robert, 3 , 15 , 47 , 96 , 99 , tracery, 100 163 , 172 Aquinas, Thomas, 8 responses to, 3 Aristotle, 7 Brenk, Beat, 82 , 162 Arnold II von Wied, archbishop of Cologne, 122 Breviary of Châteauroux, 150 Arsenal ms. 114. See Sainte-Chapelle: ordinals Brie-Comte-Robert art history Saint-Étienne “theoretical turn,” 3 triforium Autun plate tracery, 103 Saint-Lazare porch, 117 Caen Saint-Étienne Baker, Nick, 183 plate tracery, 102 Bar Sauma, 161 Cambrai Cathedral, 35 , 96 Battle of Bouvines.