A Catholic Architect Abroad: the Architectural Excursions of A.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

The Digital Nature of Gothic

The Digital Nature of Gothic Lars Spuybroek Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic is inarguably the best-known book on Gothic architecture ever published; argumentative, persuasive, passionate, it’s a text influential enough to have empowered a whole movement, which Ruskin distanced himself from on more than one occasion. Strangely enough, given that the chapter we are speaking of is the most important in the second volume of The Stones of Venice, it has nothing to do with the Venetian Gothic at all. Rather, it discusses a northern Gothic with which Ruskin himself had an ambiguous relationship all his life, sometimes calling it the noblest form of Gothic, sometimes the lowest, depending on which detail, transept or portal he was looking at. These are some of the reasons why this chapter has so often been published separately in book form, becoming a mini-bible for all true believers, among them William Morris, who wrote the introduction for the book when he published it First Page of John Ruskin’s “The with his own Kelmscott Press. It is a precious little book, made with so much love and Nature of Gothic: a chapter of The Stones of Venice” (Kelmscott care that one hardly dares read it. Press, 1892). Like its theoretical number-one enemy, classicism, the Gothic has protagonists who write like partisans in an especially ferocious army. They are not your usual historians – the Gothic hasn’t been able to attract a significant number of the best historians; it has no Gombrich, Wölfflin or Wittkower, nobody of such caliber – but a series of hybrid and atypical historians such as Pugin and Worringer who have tried again and again, like Ruskin, to create a Gothic for the present, in whatever form: revivalist, expressionist, or, as in my case, digitalist, if that is a word. -

ALBI CATHEDRAL and BRITISH CHURCH ARCHITECTURE TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 Am Page 2 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 Am Page 3

Albi F/C 24/1/2002 12:24 pm Page 1 and British Church Architecture John Thomas TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 am Page 1 ALBI CATHEDRAL AND BRITISH CHURCH ARCHITECTURE TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:24 am Page 2 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 3 ALBI CATHEDRAL and British Church Architecture 8 The in$uence of thirteenth-century church building in southern France and northern Spain upon ecclesiastical design in modern Britain 8 JOHN THOMAS THE ECCLESIOLOGICAL SOCIETY • 2002 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 4 For Adrian Yardley First published 2002 The Ecclesiological Society, c/o Society of Antiquaries of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1V 0HS www.ecclsoc.org ©JohnThomas All rights reserved Printed in the UK by Pennine Printing Services Ltd, Ripponden, West Yorkshire ISBN 0946823138 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 5 Contents List of figures vii Preface ix Albi Cathedral: design and purpose 1 Initial published accounts of Albi 9 Anewtypeoftownchurch 15 Half a century of cathedral design 23 Churches using diaphragm arches 42 Appendix Albi on the Norfolk coast? Some curious sketches by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott 51 Notes and references 63 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 6 TC Albi Cathedral 24/1/2002 11:25 am Page 7 Figures No. Subject Page 1, 2 Albi Cathedral, three recent views 2, 3 3AlbiCathedral,asillustratedin1829 4 4AlbiCathedralandGeronaCathedral,sections 5 5PlanofAlbiCathedral 6 6AlbiCathedral,apse 7 7Cordeliers’Church,Toulouse 10 8DominicanChurch,Ghent 11 9GeronaCathedral,planandinteriorview -

The Path of Saint Dominic the Path of Saint Dominic

“Sent to preach the Gospel” The Path of Saint Dominic The Path of Saint Dominic Bologna Toulouse Caleruega Rome The purpose of this guide is to help travellers and pilgrims who want to visit spirituality and the charisma he left to his Order. On his journey, the traveler will places connected with the life of St. Dominic of Guzman and therefore to have come across not only monuments but also nuns, brothers, religious people and a better understanding of the origins of the Order of Preachers. To cross, eight laities who have decided to unite to the path of Dominic and dedicate their hundred years later, the same roads, towns and to see homes and churches that lives to the mission of preaching. This is a story that remains alive because today, have marked Dominic’s itinerary, allows us to understand and to internalize the like yesterday, we are sent to preach the Gospel. CONTENTS The path of Saint Dominic ITINERARY IN SPAIN SAINT DOMINIC SAINT DOMINIC SAINT DOMINIC Gumiel de Izán Caleruega IN SPAIN IN FRANCE IN ITALY Burgo de Osma Palencia 6 CALERUEGA 14 TOULOUSE 22 BOLOGNA Saint Dominic was born here in the ... the first step of the path of Saint DOMINICAN PLACES IN BOLOGNA 1170. Dominic in France.... The Basilica and the patriarchal Convent of St. Dominic DOMINICAN PLACES AROUND DOMINIC PLACES IN TOULOUSE Segovia CALERUEGA: 23 Church of St. Mary and 14-15 Maison de Pierre Seilhan St. Dominic of “Mascarella” 7 GUMIEL DE IZAN Ancient Dominican Convent Medieval Bologna St. Dominic lived there from the age of (known as «Couvent des Jacobins») Shrine of Our Lady of St Luke seven to fourteen.. -

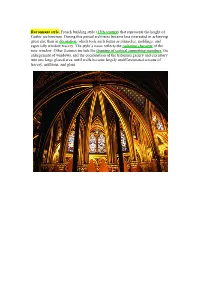

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral. -

Selling the Mission

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive Selling the mission : the German Catholic elite and the educational migration of African youngsters to Europe AITKEN, Robbie <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3332-3063> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9858/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version AITKEN, Robbie (2015). Selling the mission : the German Catholic elite and the educational migration of African youngsters to Europe. German History, 33 (1), 30- 51. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Selling the Mission: The German Catholic elite and the educational migration of African youngsters to Europei Robbie Aitken, Sheffield Hallam University In coverage of the 35th General Assembly of German Catholics held in Freiburg im Breisgau from 2-6 September 1888 a handful of local and regional newspapers remarked upon the presence of two young Africans among the guests.ii The youngsters, Mbange Akwa from Douala, Cameroon and Dagwe from Liberia, had been brought to Freiburg by Father Andreas Amrhein. -

TOP 10 Day Excursion Suggestions from Frankfurt

TOP 10 day excursion suggestions from Frankfurt Did you know that all of the many highlights waiting to be discovered in the Frankfurt Rhine- Main region can be reached in an hour or less from the Frankfurt Airport? Whether you’re off to Rüdesheim on the Rhine or Aschaffenburg on the Main, day excursions are a piece of cake! Read on and get to know our top ten destinations for short visits. The stated times are traveling times from the Frankfurt Airport. Rüdesheim / Bingen 40 min. by car / 1.20 hrs. by train In Rüdesheim and Bingen you can sit down at the winemakers table and taste culinary delights from the region. The Rheingau Region is famous for its river landscapes and vineyards, producing amongst others the well-known Riesling. A must in this part of the region is a mini-cruise on the Rhine River, an unforgettable experience! Rheingau region Wiesbaden 20 min. by car / 35 min. by train Sophisticated Wiesbaden is dominated by one Concert Hall Kurhaus colour: green! Parks and tree-lined boulevards spread throughout the city. Must-sees include the famous city theatre and the “Kurhaus” with its historical casino. Great views are guaranteed on the Neroberg Mountain, which can be climbed on the historical mountain train - already a highlight in itself. Wiesbaden is also a wonderful destination to treat yourself: why not end a day of shopping and sightseeing in the Kaiser-Friedrich- Therme, a historical Art Nouveau style bath. Rüsselsheim 15 min. by car / 10 min. by train Rüsselsheim comfortably combines both medieval and industrial history. -

2015 Program

Sixteenth Century Society and Conference S Thursday, 22 October to Sunday, 25 October 2015 Sixteenth Century Society & Conference 22–25 October 2015 2014-2015 OFFICERS President: Marc Forster Vice-President: Anne Cruz Past-President: Elizabeth Lehfeldt Executive Director: Donald J. Harreld Financial Officer: Eric Nelson ACLS Representative: Kathryn Edwards Endowmento Chairs: Raymond Mentzer COUNCIL Class of 2015: Cynthia Stollhans, Amy Leonard, Susan Felch, Matt Goldish Class of 2016: Alison Smith, Emily Michelson, Andrea Pearson, JoAnn DellaNeva Class of 2017: Rebecca Totaro,o Andrew Spicer, Gary Ferguson, Barbara Fuchs PROGRAM COMMITTEE Chair: Anne Cruz History: Scott K. Taylor English Literature: Scott Lucas German Studies: Bethany Wiggin Italian Studies: Suzanne Magnanini Theology: Rady Roldan-Figueroa French Literature: Robert Hudson Spanish and Latin American Studies: Elvira Vilches Arto History: James Clifton NOMINATING COMMITTEE Gerhild Williams (Chair), Sara Beam,o Phil Soergel, Konrad Eisenbichler, Christopher P. Baker 2014–2015 SCSC PRIZE COMMITTEES Gerald Strauss Book Prize Kenneth G. Appold, Amy Leonard, Marjorie E. Plummer Bainton Art History Book Prize Cristelle Baskins, Diane Wolfthal, Lynette Bosch Bainton History/Theology Book Prize Jill Fehleisen, Dean Bell, Craig Koslofsky Bainton Literature Book Prize Edward Friedman, WIlliam E. Engel, James H. Dahlinger Bainton Reference Book Prize Carla Zecher, Diana Robin, Phil Soergel Grimm Prize Jesse Spohnholz, Carina Johnson, Duane Corpis Roelker Prize Judy K. Kem, Allan Tulchin, -

Selling the Mission : the German Catholic Elite and the Educational

Selling the mission : the German Catholic elite and the educational migration of African youngsters to Europe AITKEN, Robbie <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3332-3063> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9858/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version AITKEN, Robbie (2015). Selling the mission : the German Catholic elite and the educational migration of African youngsters to Europe. German History, 33 (1), 30- 51. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Selling the Mission: The German Catholic elite and the educational migration of African youngsters to Europei Robbie Aitken, Sheffield Hallam University In coverage of the 35th General Assembly of German Catholics held in Freiburg im Breisgau from 2-6 September 1888 a handful of local and regional newspapers remarked upon the presence of two young Africans among the guests.ii The youngsters, Mbange Akwa from Douala, Cameroon and Dagwe from Liberia, had been brought to Freiburg by Father Andreas Amrhein. Amrhein was the founder of the Benedictine Mission Society, based at St Ottilien near Munich, where the youngsters were being educated. He was a proponent of Catholic involvement in the German colonial project and the fledgling mission had already sent its first missionaries to German East Africa the previous year. During the Assembly Mbange and Dagwe were photographed alongside Ludwig Windthorst, the prominent politician and leader of the Catholic Centre Party, who, according to reports, was to take on the role of their godfather.iii Following the establishment of an overseas empire in 1884 he became increasingly vocal in calling for Catholics to be granted permission to missionize in the new German territories. -

Lavoce's Directory

July 31, 2015 To Whom It May Concern: Promote Your Business with Lavoce’s Directory! Welcome to the preliminary edition of Lavoce’s Directory! Lavoce: We Are People Too, Inc. (Lavoce) is proud to present the first international directory for Goths, tattoo artists, sKateboarders, and others who live alternative lifestyles, or anyone whose clothing is outside the norm. This directory has more categories than any other online Goth directory. This is the most comprehensive directory available because being Goth affects all aspects of life. Our commitment is driven by the need to help Goths, and others who looK outside the norm, to feel safe to be themselves in their day-to-day jobs. This directory is the first and only directory of employers who hire people from alternative lifestyles. It has the potential to connect those who feel alone in this world to established organizations and areas of the world where Goths feel more accepted. It will build sustaining partnerships with existing organizations and revitalize the community by helping new organizations grow. Lavoce will also support Goth jobseeKers to promote job sKills training and worKplace etiquette. If you are seeing this, then you are an employer that seems open to hiring people from alternative lifestyles. I am writing to encourage your company to come forward as an openminded employer. The entries in this directory are gray because they have only been proposed but have not yet been confirmed or paid. I have included your company’s link in the first edition of this directory, but will need further information from you going forward. -

Curriculum Vitae Page 1 of 23

Jennifer Mara DeSilva – Curriculum Vitae Page 1 of 23 Dr. Jennifer Mara DeSilva – Curriculum Vitae April 1, 2021 PERSONAL Office Address: Department of History, Burkhardt Building, Room 212, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana, 47306-1099, USA E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Toronto, Department of History, Canada, November 2007 Thesis title: “Ritual Negotiations: Paris de’ Grassi and the Office of Ceremonies under Popes Julius II & Leo X” Supervisor: Dr. Nicholas Terpstra M.A. University of Warwick, Coventry, UK, January 2002 Centre for the Study of the Renaissance Subject: The Culture of the European Renaissance Thesis title: “Henry VIII King of England and Papal Honour-gifts, 1510-24” Thesis Readers: Drs. Peter Marshall and J.R. Mulryne Hon. B.A. St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto, Canada, June 1999 Specialist: History Major: Latin Minor: English EMPLOYMENT Fall 2015-onward Associate Professor (Tenured), Ball State University, Muncie IN, USA 2010-Summer 2015 Assistant Professor, Ball State University, Muncie IN, USA Graduate Faculty Member Courses taught, all face-to-face unless otherwise indicated: HIST 150: The West in the World HIST 151: World Civilization I (also taught online) HIST 200: Introduction to History and Historical Methods HIST 467/567: The Renaissance & The Reformation HIST 497/597: Social History of Renaissance Europe HIST 633: Ritual and Spectacle in Early Modern Europe HIST 650: European Conversion to Christianity, 300-1000 HIST 650: Comparative European Chivalry, 1300-1650 HIST