HOWELL-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (9.632Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander B. Hill Script Supervisor IATSE Local 161 421 S Pierce St., New Orleans, LA 70119 • 504-491-8766 • [email protected]

Alexander B. Hill Script Supervisor IATSE Local 161 421 S Pierce St., New Orleans, LA 70119 • 504-491-8766 • [email protected] *Certified with ScriptE digital script supervising software. * Temple (2016) WWE Studios (Main Unit) Dir: John Stockwell, Prod: Ralph Portillo UPM: John Brister Cast: Wesley Snipes, Anne Heche, Dave Annable Scream Season 2 (2016) MTV Network, Next Productions (Additional Script Supervisor) Dir: Patrick Lussier, UPM: Heidi Erl Cast: Willa Fitzgerald, Bex Klaus, Amadeus Serafini The Passion (2016) FOX Television, Dick Clark Productions (Main Unit) Dir: Robert Deaton, Prod: Mark Kalbfeld Cast: Jencarlos Canela, Prince Royce, Chris Daughtry Brother’s Blood (2016) WWE Studios (Main Unit) Dir: John Pogue, Prod: Ralph Portillo UPM: John Brister Cast: Trey Songz, China Anne McClain Roots (2015-16) A&E Television Series (2nd Unit) Dir: Philip Noyce POC: Sam Horton Cast: Lawrence Fishburne, Forest Whitaker NCIS: NOLA – Season 2 (2015) NBC Television (2nd Unit) Dir: Ed Ornelas, Prod: Joseph Zolfo Co-Prod: Rob Ortiz Cast: Scott Bakula, Zoe McClellan My Invisible Sister (2015) Disney Channel Movie (Main Unit) Dir: Paul Hoen, Prod: Michael Cuddy Prod Sup: Paige Pemberton Cast: Rowan Blanchard, Paris Berelc, Karan Brar Zoo - Season 1 (2015) CBS Television Studios (Main Unit - 5 episodes) Dir: Michael Katleman, Zetna Fuentes, Prod: Todd Coe UPM: Rob Ortiz Cast: Billy Burke, Kristin Connolly, James Wolk The Long Night / Deepwater Horizon (2015) Long Night Productions (2nd Unit) Dir: Peter Berg, Prod: Lorenzo di Bonaventura, 2nd Unit UPM: Elona Tsou Cast: Mark Wahlberg, Kurt Russell, Kate Hudson Into the Badlands (2015) AMC Series (2nd Unit) Dir: Miles Millar, Prod: Henry Bronchtein, UPM: Christian Agypt Cast: Marton Csokas, Daniel Wu, Aramis Knight 1 GOMD (2015) Lord Danger Pictures (Music Video) Dir: Lawrence Lamont, Prod: Josh Shadid UPM: Meghan Kaltenbach Cast: J. -

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) PAUL SPARKS

Cast Biographies RILEY KEOUGH (Christine Reade) Riley Keough, 26, is one of Hollywood’s rising stars. At the age of 12, she appeared in her first campaign for Tommy Hilfiger and at the age of 15 she ignited a media firestorm when she walked the runway for Christian Dior. From a young age, Riley wanted to explore her talents within the film industry, and by the age of 19 she dedicated herself to developing her acting craft for the camera. In 2010, she made her big-screen debut as Marie Currie in The Runaways starring opposite Kristen Stewart and Dakota Fanning. People took notice; shortly thereafter, she starred alongside Orlando Bloom in The Good Doctor, directed by Lance Daly. Riley’s memorable work in the film, which premiered at the Tribeca film festival in 2010, earned her a nomination for Best Supporting Actress at the Milan International Film Festival in 2012. Riley’s talents landed her a title-lead as Jack in Bradley Rust Gray’s werewolf flick Jack and Diane. She also appeared alongside Channing Tatum and Matthew McConaughey in Magic Mike, directed by Steven Soderbergh, which grossed nearly $167 million worldwide. Further in 2011, she completed work on director Nick Cassavetes’ film Yellow, starring alongside Sienna Miller, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liota, as well as the Xan Cassavetes film Kiss of the Damned. As her camera talent evolves alongside her creative growth, so do the roles she is meant to play. Recently, she was the lead in the highly-anticipated fourth installment of director George Miller’s cult- classic Mad Max - Mad Max: Fury Road alongside a distinguished cast comprising of Tom Hardy, Charlize Theron, Zoe Kravitz and Nick Hoult. -

Production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and Later Played The

‘ONCE UPON A CHRISTMAS MIRACLE’ Cast Bios AIMEE TEEGARDEN (Heather Krueger) – A California native, Aimee Teegarden began her acting career at just 10 years old. When she was 16, she was cast in her first television series on the Emmy-nominated “Friday Night Lights” playing Julie Taylor, the elder daughter of a high school head football coach (Kyle Chandler) and a high school guidance counselor (Connie Britton). Most recently, Teegarden starred on the ABC series, “Notorious,” opposite Daniel Sunjata and Piper Perabo. In 2014, she starred in the science fiction romantic drama series for The CW, “Star-Crossed.” She can also be seen in the Paramount film Rings as well as the independent film Bakery in Brooklyn. Her previous film credits include Scream 4, Love and Honor and Disney’s Prom. Teegarden is an avid fitness enthusiast, competing in the 2016 Chicago Spartan Race and running a half marathon with Team Nike. She is also on the host committee of the ocean conservation organization Oceana, and an advocate for No-Kill Los Angeles (NKLA), an initiative of the Best Friends Animal Society to end the overpopulation of dogs and cats in LA city shelters. # # # BRETT DALTON (Chris Dempsey) – Brett Dalton began acting after auditioning for a production of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and later played the lead in My Favorite Year. After studying at University of California, Berkeley for his undergraduate degree, Dalton received a Master of Fine Arts from Yale University in 2011. After grad school, Dalton appeared in the indie dramedy, Beside Still Waters, co-written, produced and directed by Chris Lowell. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

9 VITE DA DONNA Regia : Rodrigo Garcia (2005)

9 VITE DA DONNA Regia : Rodrigo Garcia (2005) 9 VITE DA DONNA (Nine lives) Genere: Drammatico Regia: Rodrigo Garcia Interpreti: Elpidia Carrillo (Sandra), Miguel Sandoval (Ron, guardia), Robin Wright Penn (Diana), Lisa Gay Hamilton (Holly), Holly Hunter (Sonia), Amanda Seyfried (Samantha), Amy Brenneman (Lorna), Sissy Spacek (Ruth), Kathy Baker (Camille), Glenn Close (Maggie), Dakota Fanning (Maria), Jason Isaacs (Damian), Aidan Quinn (Henry), Stephen Dillane (Martin), Molly Parker (Lisa), Joe Mantegna (Richard), Ian McShane (Larry), Mary Kay Place (Alma). Nazionalità: Stati Uniti Distribuzione: Mikado Film Anno di uscita: 2005 Orig.: Stati Uniti (2004) Sogg. e scenegg.: Rodrigo Garcia Fotogr.(Panoramica/a colori): Xavier Perez Grobet Mus.: Edward Shearmur Montagg.: Andrea Folpre cht Dur.: 112´ Produz.: Julie Lynn. Giudizio: Discutibile/ambiguità Tematiche: Aborto; Carcere; Donna; Famiglia - genitori figli; Malattia; Matrimonio - coppia; Soggetto: Nove episodi. SANDRA (Una ragazza madre in carcere). DIANA (Incinta, al supermercato incontra un antico spasimante). HOLLY (Lei e la sorella aspettano il padre violentatore). SONIA (con il marito in visita a casa di amici). SAMMY (Vive con i genitori, il padre paralitico). LORNA (Va al funerale della moglie dell´ex marito). RUTH (Al motel, vorrebbe provare a tradire il marito, ma non ci riesce). CAMILLE (In ospedale, aspetta l´operazione di mastectomia). MAGGIE (Va con la nipotina Maria al cimitero sulla tomba del marito). Valutazione Pastorale: I nove ritratti scritti e messi in immagini da Rodrigo Garcia (figlio di Gabriel Garcia Marquez) hanno l´obiettivo di focalizzare alcune situazioni di difficoltà che il mondo femminile si trova oggi ad affrontare e sopportare. Va detto che la qualità dei nove capitoletti é abbastanza diseguale: il più compatto é forse quello dedicato a Camille in ospedale; gli altri ondeggiano nella esposizione di problemi vari e certo tutti realistici (il carcere, la maternità, il matrimonio, l´equilibrio tra privato e pubblico...) ma non sempre ben centrati. -

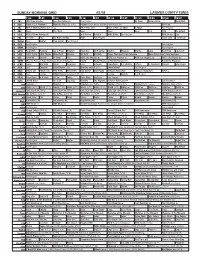

Sunday Morning Grid 4/1/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/1/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program JB Show History Astro. Basketball 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Boston Bruins at Philadelphia Flyers. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid NBA Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Jazzy Real Food Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Misa de Pascua: Papa Francisco desde el Vaticano Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Henley's the Wake of Jamie Foster and the Miss Firecracker Contest

‘SNOW BRIDE’ CAST BIOS PATRICIA RICHARDSON (Maggie Tannenhill) – Patricia Richardson is best known for her portrayal of Jill Taylor on the long running series “Home Improvement” in which she co-starred with Tim Allen. For her work on the series, she received four Emmy® nominations and two Golden Globe® nominations as Outstanding Lead Actress in a Comedy Series. While performing in “Home Improvement,” she also co-hosted the Emmy® Awards with Ellen DeGeneres. In 2009, the cast members of “Home Improvement” received a Fan Favorite Award from the TV Land Awards. She has also received a Vision Award and a Women In Film Award in Texas and commendations from the Prism Awards for her work in the show. For two years, she had a recurring role in “The West Wing” as Sheila Brooks, Sen. Arnold Vinick’s (Alan Alda) chief of staff. She was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award for her role in “Ulee’s Gold,” opposite Peter Fonda and directed by Victor Nunez. Previously, Richardson garnered rave reviews for her portrayal of Marilyn Monroe’s mother in the CBS miniseries “Blonde.” She played twins in “Viva Las Nowhere,” co-starring Danny Stern and James Caan, which was released on video under the title “Dead Simple” and won a Seattle Film Festival Award. She received more great reviews for her role in Lifetime’s “Sophie & the Moonhanger,” co-starring Lynn Whitfield and Jason Bernard and “Undue Influence,” with Brian Dennehy. Other films include “Lost Angels,” “In Country” and “Beautiful Wave.” She was brought out to Los Angeles from New York after several years of doing theater, first by Norman Lear and then Alan Burns, to do three different series prior to “Home Improvement” - “Double Trouble” for Lear and then “Eisenhower and Lutz” and “FM” for Burns. -

Full Transcript

Jane Hall: Hello and welcome to American Forum Café, a podcast production of the School of Communication at American University in Washington DC. I'm Jane Hall, I'm an associate professor here at SOC. I teach courses on politics in the media and advanced reporting. Before coming to AU I was a journalist covering the news media for many years in New York. In my Politics in the Media class we look at the intersection of contemporary politics and media coverage, and boy are politics and the media intersecting. Colliding, actually, and influencing each other. As part of my class students have the opportunity to participate in American Forum Town Halls and one on one conversations with journalists, political strategists, politicians, and other important players. My students in Advanced Reporting also play an important role in our programs. They are interviewing other college students about our topics as well as asking our guests questions during our events. Jane Hall: Recently, Congressman Steve Cohen, Democrat from Tennessee spoke with my classes and other students at AU. What you'll hear on this episode is the recording from that event. Congressman Cohen is best known for introducing Articles of Impeachment last year against Donald Trump. With the Democrats winning a majority in the House of Representatives impeachment had become a real possibility. And Congressman Cohen is chair of an important subcommittee on the House Judiciary Committee where impeachment could begin. He is playing an important role in other committees as well. He is the first Jewish Congressman from Tennessee, as well as he represents a majority black district. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

KATHLEEN FELIX-HAGER Costume Designer

KATHLEEN FELIX-HAGER Costume Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS HACKS Lucia Aniello HBO MAX / UNIVERSAL TV Season 1 Morgan Sackett, Lucia Aniello Nominated, Outstanding Contemporary Mike Schur, David Miner, Jen Statsky Costumes – Emmy Awards Paul W. Downs HAPPIEST SEASON Clea Duvall HULU / TEMPLE HILL / SONY Feature Jonathan McCoy, Nicolas Stern Isaac Klausner, Marty Bowen SPACE FORCE Various Directors NETFLIX Pilot & Series Caroline James, Greg Daniels DOWNHILL Feature Jim Rash FOX SEARCHLIGHT Official Selection – Sundance Film Festival Nat Faxon Jo Homewood, Anthony Bregman VEEP Armando Iannucci HBO / Morgan Sackett Seasons 3 - 7 Various Directors Stephanie Laing, Armando Iannucci FOR LOVE John Dahl ABC Pilot Trish Hoffman, Kim Moses UPLOAD Various Directors AMAZON STUDIOS / Jill Danton Pilot Greg Daniels, Howard Klein GETTING ON Howard Deutch ANIMA SOLA PRODUCTIONS / HBO Season 3 Various Directors Chrisann Verges HEARTBEAT Robbie McNeill UNIVERSAL / NBC / Amy Brenneman Pilot Kelly Meyer, Gordon Mark DEXTER John Dahl SHOWTIME Costume Designer Seasons 6 - 8 SJ Clarkson Robert Lewis, Gary Law, Arika Mittman Costume Supervisor Seasons 1 - 5 Various Directors INTERCEPT Kevin Hooks ABC FAMILY Pilot Lynn Raynor SALVATION BOULEVARD Feature George Ratliff LIONSGATE Costume Supervisor Cathy Schulman TEEN SPIRIT Gil Junger ABC FAMILY MOW Steven Gary Banks, James Middleton CHRISTMAS CUPID Gil Junger ABC FAMILY / Craig McNeil MOW JUDGING AMY Various Directors CBS Seasons 3 – 6 Dan Sackheim, Barbara Hall EASTWICK Series David Nutter ABC Costume Supervisor David Nutter THE WEST WING Season 2 Various Directors NBC Costume Supervisor Aaron Sorkin, John Wells INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 . -

Pennsylvania History

Pennsylvania History a journal of mid-atlantic studies PHvolume 80, number 2 · spring 2013 “Under These Classic Shades Together”: Intimate Male Friendships at the Antebellum College of New Jersey Thomas J. Balcerski 169 Pennsylvania’s Revolutionary Militia Law: The Statute that Transformed the State Francis S. Fox 204 “Long in the Hand and Altogether Fruitless”: The Pennsylvania Salt Works and Salt-Making on the New Jersey Shore during the American Revolution Michael S. Adelberg 215 “A Genuine Republican”: Benjamin Franklin Bache’s Remarks (1797), the Federalists, and Republican Civic Humanism Arthur Scherr 243 Obituaries Ira V. Brown (1922–2012) Robert V. Brown and John B. Frantz 299 Gerald G. (Gerry) Eggert (1926–2012) William Pencak 302 bOOk reviews James Rice. Tales from a Revolution: Bacon’s Rebellion and the Transformation of Colonial America Reviewed by Matthew Kruer 305 This content downloaded from 128.118.153.205 on Mon, 15 Apr 2019 13:08:47 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Sally McMurry and Nancy Van Dolsen, eds. Architecture and Landscape of the Pennsylvania Germans, 1720-1920 Reviewed by Jason R. Sellers 307 Patrick M. Erben. A Harmony of the Spirits: Translation and the Language of Community in Early Pennsylvania Reviewed by Karen Guenther 310 Jennifer Hull Dorsey. Hirelings: African American Workers and Free Labor in Early Maryland Reviewed by Ted M. Sickler 313 Kenneth E. Marshall. Manhood Enslaved: Bondmen in Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century New Jersey Reviewed by Thomas J. Balcerski 315 Jeremy Engels. Enemyship: Democracy and Counter-Revolution in the Early Republic Reviewed by Emma Stapely 318 George E. -

2018 – Volume 6, Number

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 6 NUMBER 2 & 3 2018 Editor NORMA JONES Liquid Flicks Media, Inc./IXMachine Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor KEVIN CALCAMP Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor JESSICA BENHAM University of Pittsburgh Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture- studies-journal/ The Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2018 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 Cover credit: Cover Artwork: “Bump in the Night” by Brent Jones © 2018 Courtesy of Pixabay/Kellepics EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD ANTHONY ADAH PAUL BOOTH Minnesota State University, Moorhead DePaul University GARY BURNS ANNE M. CANAVAN Northern Illinois University Salt Lake Community College BRIAN COGAN ASHLEY M. DONNELLY Molloy College Ball State University LEIGH H. EDWARDS KATIE FREDICKS Florida State University Rutgers University ART HERBIG ANDREW F. HERRMANN Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne East Tennessee State University JESSE KAVADLO KATHLEEN A. KENNEDY Maryville University of St. Louis Missouri State University SARAH MCFARLAND TAYLOR KIT MEDJESKY Northwestern University University of Findlay CARLOS D. MORRISON SALVADOR MURGUIA Alabama State University Akita International