Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 Sota3 Chapter 7 REV11

200 Until recently, quantifying rates of tropical forest destruction was challenging and laborious. © Jabruson 2017 (www.jabruson.photoshelter.com) forest quantifying rates of tropical Until recently, Photo: State of the Apes Infrastructure Development and Ape Conservation 201 CHAPTER 7 Mapping Change in Ape Habitats: Forest Status, Loss, Protection and Future Risk Introduction This chapter examines the status of forested habitats used by apes, charismatic species that are almost exclusively forest-dependent. With one exception, the eastern hoolock, all ape species and their subspecies are classi- fied as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (IUCN, 2016c). Since apes require access to forested or wooded land- scapes, habitat loss represents a major cause of population decline, as does hunting in these settings (Geissmann, 2007; Hickey et al., 2013; Plumptre et al., 2016b; Stokes et al., 2010; Wich et al., 2008). Until recently, quantifying rates of trop- ical forest destruction was challenging and laborious, requiring advanced technical Chapter 7 Status of Apes 202 skills and the analysis of hundreds of satel- for all ape subspecies (Geissmann, 2007; lite images at a time (Gaveau, Wandono Tranquilli et al., 2012; Wich et al., 2008). and Setiabudi, 2007; LaPorte et al., 2007). In addition, the chapter projects future A new platform, Global Forest Watch habitat loss rates for each subspecies and (GFW), has revolutionized the use of satel- uses these results as one measure of threat lite imagery, enabling the first in-depth to their long-term survival. GFW’s new analysis of changes in forest availability in online forest monitoring and alert system, the ranges of 22 great ape and gibbon spe- entitled Global Land Analysis and Dis- cies, totaling 38 subspecies (GFW, 2014; covery (GLAD) alerts, combines cutting- Hansen et al., 2013; IUCN, 2016c; Max Planck edge algorithms, satellite technology and Insti tute, n.d.-b). -

PASA 2005 Final Report.Pdf

PAN AFRICAN SANCTUARY ALLIANCE 2005 MANAGEMENT WORKSHOP REPORT 4-8 June 2005 Mount Kenya Safari Lodge, Nanyuki, Kenya Hosted by Pan African Sanctuary Alliance / Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary Photos provided by Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary – Sierra Leone (cover), PASA member sanctuaries, and Doug Cress. A contribution of the World Conservation Union, Species Survival Commission, Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) and Primate Specialist Group (PSG). © Copyright 2005 by CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Prepared by participants in the PASA 2005 Management Workshop, Mount Kenya, Kenya, 4th – 8th June 2005 W. Mills, D. Cress, & N. Rosen (Editors). Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2005. Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report. Additional copies of the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation -

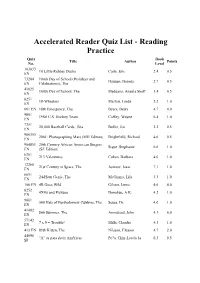

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Identification of Subspecies and Parentage Relationship by Means of DNA Fingerprinting in Two Exemplary of Pan Troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1775) (Mammalia Hominidae)

Biodiversity Journal , 2018, 9 (2): 107–114 DOI: 10.31396/Biodiv.Jour.2018.9.2.107.114 Identification of subspecies and parentage relationship by means of DNA fingerprinting in two exemplary of Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1775) (Mammalia Hominidae) Viviana Giangreco 1, Claudio Provito 1, Luca Sineo 2, Tiziana Lupo 1, Floriana Bonanno 1 & Stefano Reale 1* 1Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale della Sicilia “A. Mirri”, Via G. Marinuzzi 3, 90129 Palermo, Italy 2Biologia animale e Antropologia, Dip. STEBICEF, Via Archirafi 18, 90123 Palermo, Italy *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Four chimpanzee subspecies (Mammalia Hominidae) are commonly recognised: the West - ern Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes verus (Schwarz, 1934), the Nigeria-Cameroon Chim - panzee, P. troglodytes ellioti, the Central Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1799), and the Eastern Chimpanzee, P. troglodytes schweinfurthii (Giglioli, 1872). Recent studies on mitochondrial DNA show the incorporation of P. troglodytes schweinfurthii in P. troglodytes troglodytes , suggesting the existence of only two sub - species: P. troglodytes troglodytes in Central and Eastern Africa and P. troglodytes verus- P. troglodytes ellioti in West Africa. The aim of the present study is twofold: first, to identify the correct subspecies of two chimpanzee samples collected in a Biopark structure in Carini (Sicily, Italy), and second, to verify whether there was a kinship relationship be - tween the two samples through techniques such as DNA barcoding and microsatellite analysis. DNA was extracted from apes’ buccal swabs, the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI) gene was amplified using universal primers, then purified and injected into capillary electrophoresis Genetic Analyzer ABI 3130 for sequencing. The sequence was searched on the NCBI Blast database. -

Ebola & Great Apes

Ebola & Great Apes Ebola is a major threat to the survival of African apes There are direct links between Ebola outbreaks in humans and the contact with infected bushmeat from gorillas and chimpanzees. In the latest outbreak in West Africa, Ebola claimed more than 11,000 lives, but the disease has also decimated great ape populations during previous outbreaks in Central Africa. What are the best strategies for approaching zoonotic diseases like Ebola to keep both humans and great apes safe? What is Ebola ? Ebola Virus Disease, formerly known as Ebola Haemorrhagic Fever, is a highly acute, severe, and lethal disease that can affect humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas. It was discovered in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and is a Filovirus, a kind of RNA virus that is 50-100 times smaller than bacteria. • The initial symptoms of Ebola can include a sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Subsequent stages include vomiting, diarrhoea and, in some cases, both internal and external bleeding. • Though it is believed to be carried in bat populations, the natural reservoir of Ebola is unknown. A reservoir is the long-term host of a disease, and these hosts often do not contract the disease or do not die from it. • The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals through the consumption and handling of wild meats, also known as bushmeat, and spreads in the human population via human-to-human transmission through contact with bodily fluids. • The average Ebola case fatality rate is around 50%, though case fatality rates have varied from 25% to 90%. -

Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 With an Open Heart: Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC WITH AN OPEN HEART: FOLIA DE REIS, A BRAZILIAN SPIRITUAL JOURNEY THROUGH SONG By WELSON ALVES TREMURA A Dissertation submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2004 Copyright 2004 Welson Alves Tremura All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Welson Alves Tremura defended on April 5, 2004. _____________________________ Dale A. Olsen Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Anthony Oliver-Smith Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member _____________________________ Larry Crook Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The folia de reis high-pitched voices singing in the distance are memories of a childhood of music and celebrations that go back to the early 1970s when playing soccer in a field not larger than a basketball court or flying a kite were the highest point of most children in that part of Brazil. The folia groups could be heard in the distance with the tala or high pitch voice singing the last part of the refrain. These sounds could typically be heard echoing throughout the surrounding neighborhoods of Olímpia, São Paulo during the second half of the month of December and early part of January. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Chimpanzee

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDIX I AND II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Governments of Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania have jointly submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) on Appendix I and II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDICES I AND II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A: PROPOSAL Inclusion of Pan troglodytes in Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. B: PROPONENTS: Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania C: SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Primates 1.3 Family: Hominidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach 1775) (Wilson & Reeder 2005) [Note: Pan troglodytes is understood in the sense of Wilson and Reeder (2005), the current reference for terrestrial mammals used by CMS). -

ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT

ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 1/84 EO PT No. ICC-01/09-02/11 21-4-11 ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT A PROGRESS REPORT TO THE HON. ATTORNEY-GENERAL BY THE TEAM ON UPDATE OF POST ELECTION VIOLENCE RELATED CASES IN WESTERN, NYANZA, CENTRAL, RIFT-VALLEY, EASTERN, COAST AND NAIROBI PROVINCES MARCH, 2011 NAIROBI ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 3/84 EO PT TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER SUBJECT PAGE TRANSMITTAL LETTER IV 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. GENDER BASED VIOLENCE CASES 7 3. WESTERN PROVINCE 24 3. RIFT VALLEY PROVINCE 30 4. NYANZA PROVINCE 47 5. COAST PROVINCE 62 6. NAIROBI PROVINCE 66 7. CENTRAL PROVINCE 69 8. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 70 9. CONCLUSION 73 10. APPENDICES ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 4/84 EO PT APPENDIX (NO.) LIST OF APPENDICES APP. 1A - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1B - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1C - Update on 2007 Post Election Violence offences As at 4th March, 2010 (police commissioner’s report) APP. 1D - Update by Taskforce on Gender Based Violence Cases (police commissioner’s report) APP. 2 - Memo to Solicitor- General from CPP APP. 3 - Letter from PCIO Western APP. 4 - Letter from PCIO Rift Valley APP.5 - Cases Pending Under Investigations in Rift Valley on special interest cases APP.6 - Cases where suspects are known in Rift Valley but have not been arrested APP.7 - Letter from PCIO Nyanza APP.8 - Letter from PCIO Coast APP.9 - Letter from PCIO Nairobi APP.10 - Correspondences from the team ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 5/84 EO PT The Hon. -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Duncan Public Library Board of Directors Meeting Minutes June 23, 2020 Location: Duncan Public Library

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: August 25, 2020 Time: 9:30 am Place: Zoom Meeting 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from July 28, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for June. 4. Presentation of library claims for June. Approval. 5. Director’s report a. Summer reading program b. Genealogy Library c. StoryWalk d. Annual report to ODL e. Sept. Library Card Month f. DALC grant for Citizenship Corner g. After-school snack program 6. Consider a list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed books be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 7. Consider approving creation of a Student Library Card and addition of policy to policy manual. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Duncan Public Library Claims for July 1 through 31, 2020 Submitted to Library Board, August 25, 2020 01-11-521400 Materials & Supplies 20-1879 Demco......................................................................................................................... $94.94 Zigzag shelf, children’s 20-2059 Quill .......................................................................................................................... $589.93 Tissue, roll holder, paper, soap 01-11-522800 Phone/Internet 20-2222 AT&T ........................................................................................................................... $41.38 -

The Evolutionary History of Human and Chimpanzee Y-Chromosome Gene Loss

The Evolutionary History of Human and Chimpanzee Y-Chromosome Gene Loss George H. Perry,* à Raul Y. Tito,* and Brian C. Verrelli* *Center for Evolutionary Functional Genomics, The Biodesign Institute, Arizona State University, Tempe; School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe; and àSchool of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University, Tempe Recent studies have suggested that gene gain and loss may contribute significantly to the divergence between humans and chimpanzees. Initial comparisons of the human and chimpanzee Y-chromosomes indicate that chimpanzees have a dis- proportionate loss of Y-chromosome genes, which may have implications for the adaptive evolution of sex-specific as well as reproductive traits, especially because one of the genes lost in chimpanzees is critically involved in spermatogenesis in humans. Here we have characterized Y-chromosome sequences in gorilla, bonobo, and several chimpanzee subspecies for 7 chimpanzee gene–disruptive mutations. Our analyses show that 6 of these gene-disruptive mutations predate chimpan- zee–bonobo divergence at ;1.8 MYA, which indicates significant Y-chromosome change in the chimpanzee lineage Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/24/3/853/1246230 by guest on 23 September 2021 relatively early in the evolutionary divergence of humans and chimpanzees. Introduction The initial comparisons of human and chimpanzee Comparative analyses of single-nucleotide differences (Pan troglodytes) Y-chromosome sequences revealed that between human and chimpanzee genomes typically show although there are no lineage-specific gene-disruptive mu- estimates of approximately 1–2% divergence (Watanabe tations in the X-degenerate portion of the Y-chromosome et al. 2004; Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consor- fixed within humans, surprisingly, 4 genes, CYorf15B, tium 2005). -

Williams Dissertation

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Don't Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0jf3488f Author Williams, Joshua Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Don’t Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa by Joshua Drew Montgomery Williams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Catherine Cole, Chair Professor Donna Jones Professor Samera Esmeir Professor Brandi Wilkins Catanese Spring 2017 Abstract Don’t Show A Hyena How Well You Can Bite: Performance, Race and the Animal Subaltern in Eastern Africa by Joshua Drew Montgomery Williams Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Catherine Cole, Chair This dissertation explores the mutual imbrication of race and animality in Kenyan and Tanzanian politics and performance from the 1910s through to the 1990s. It is a cultural history of the non- human under conditions of colonial governmentality and its afterlives. I argue that animal bodies, both actual and figural, were central to the cultural and