Williams Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid

Circus Friends Association Collection Finding Aid University of Sheffield - NFCA Contents Poster - 178R472 Business Records - 178H24 412 Maps, Plans and Charts - 178M16 413 Programmes - 178K43 414 Bibliographies and Catalogues - 178J9 564 Proclamations - 178S5 565 Handbills - 178T40 565 Obituaries, Births, Death and Marriage Certificates - 178Q6 585 Newspaper Cuttings and Scrapbooks - 178G21 585 Correspondence - 178F31 602 Photographs and Postcards - 178C108 604 Original Artwork - 178V11 608 Various - 178Z50 622 Monographs, Articles, Manuscripts and Research Material - 178B30633 Films - 178D13 640 Trade and Advertising Material - 178I22 649 Calendars and Almanacs - 178N5 655 1 Poster - 178R47 178R47.1 poster 30 November 1867 Birmingham, Saturday November 30th 1867, Monday 2 December and during the week Cattle and Dog Shows, Miss Adah Isaacs Menken, Paris & Back for £5, Mazeppa’s, equestrian act, Programme of Scenery and incidents, Sarah’s Young Man, Black type on off white background, Printed at the Theatre Royal Printing Office, Birmingham, 253mm x 753mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.2 poster 1838 Madame Albertazzi, Mdlle. H. Elsler, Mr. Ducrow, Double stud of horses, Mr. Van Amburgh, animal trainer Grieve’s New Scenery, Charlemagne or the Fete of the Forest, Black type on off white backgound, W. Wright Printer, Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, 205mm x 335mm Circus Friends Association Collection 178R47.3 poster 19 October 1885 Berlin, Eln Mexikanermanöver, Mr. Charles Ducos, Horaz und Merkur, Mr. A. Wells, equestrian act, C. Godiewsky, clown, Borax, Mlle. Aguimoff, Das 3 fache Reck, gymnastics, Mlle. Anna Ducos, Damen-Jokey-Rennen, Kohinor, Mme. Bradbury, Adgar, 2 Black type on off white background with decorative border, Druck von H. G. -

PASA 2005 Final Report.Pdf

PAN AFRICAN SANCTUARY ALLIANCE 2005 MANAGEMENT WORKSHOP REPORT 4-8 June 2005 Mount Kenya Safari Lodge, Nanyuki, Kenya Hosted by Pan African Sanctuary Alliance / Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary Photos provided by Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary – Sierra Leone (cover), PASA member sanctuaries, and Doug Cress. A contribution of the World Conservation Union, Species Survival Commission, Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) and Primate Specialist Group (PSG). © Copyright 2005 by CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Prepared by participants in the PASA 2005 Management Workshop, Mount Kenya, Kenya, 4th – 8th June 2005 W. Mills, D. Cress, & N. Rosen (Editors). Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2005. Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report. Additional copies of the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation -

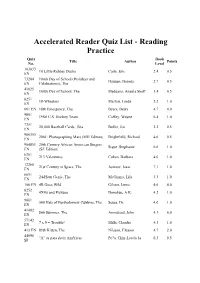

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 With an Open Heart: Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC WITH AN OPEN HEART: FOLIA DE REIS, A BRAZILIAN SPIRITUAL JOURNEY THROUGH SONG By WELSON ALVES TREMURA A Dissertation submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2004 Copyright 2004 Welson Alves Tremura All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Welson Alves Tremura defended on April 5, 2004. _____________________________ Dale A. Olsen Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Anthony Oliver-Smith Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member _____________________________ Larry Crook Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The folia de reis high-pitched voices singing in the distance are memories of a childhood of music and celebrations that go back to the early 1970s when playing soccer in a field not larger than a basketball court or flying a kite were the highest point of most children in that part of Brazil. The folia groups could be heard in the distance with the tala or high pitch voice singing the last part of the refrain. These sounds could typically be heard echoing throughout the surrounding neighborhoods of Olímpia, São Paulo during the second half of the month of December and early part of January. -

Animal Representations, Anthropomorphism, and Några Tillfällen – Kommer Frågan Om Subjektivi- Interspecies Relations in the Little Golden Books

Samlaren Tidskrift för forskning om svensk och annan nordisk litteratur Årgång 139 2018 I distribution: Eddy.se Svenska Litteratursällskapet REDAKTIONSKOMMITTÉ: Berkeley: Linda Rugg Göteborg: Lisbeth Larsson Köpenhamn: Johnny Kondrup Lund: Erik Hedling, Eva Hættner Aurelius München: Annegret Heitmann Oslo: Elisabeth Oxfeldt Stockholm: Anders Cullhed, Anders Olsson, Boel Westin Tartu: Daniel Sävborg Uppsala: Torsten Pettersson, Johan Svedjedal Zürich: Klaus Müller-Wille Åbo: Claes Ahlund Redaktörer: Jon Viklund (uppsatser) och Sigrid Schottenius Cullhed (recensioner) Biträdande redaktör: Niclas Johansson och Camilla Wallin Bergström Inlagans typografi: Anders Svedin Utgiven med stöd av Vetenskapsrådet Bidrag till Samlaren insändes digitalt i ordbehandlingsprogrammet Word till [email protected]. Konsultera skribentinstruktionerna på sällskapets hemsida innan du skickar in. Sista inläm- ningsdatum för uppsatser till nästa årgång av Samlaren är 15 juni 2019 och för recensioner 1 sep- tember 2019. Samlaren publiceras även digitalt, varför den som sänder in material till Samlaren därmed anses medge digital publicering. Den digitala utgåvan nås på: http://www.svelitt.se/ samlaren/index.html. Sällskapet avser att kontinuerligt tillgängliggöra även äldre årgångar av tidskriften. Svenska Litteratursällskapet tackar de personer som under det senaste året ställt sig till för- fogande som bedömare av inkomna manuskript. Svenska Litteratursällskapet PG: 5367–8. Svenska Litteratursällskapets hemsida kan nås via adressen www.svelitt.se. isbn 978–91–87666–38–4 issn 0348–6133 Printed in Lithuania by Balto print, Vilnius 2019 Recensioner av doktorsavhandlingar · 241 vitet. Men om medier, med Marshall McLuhan, Kelly Hübben, A Genre of Animal Hanky-panky? är proteser – vilket Gardfors skriver under på vid Animal Representations, Anthropomorphism, and några tillfällen – kommer frågan om subjektivi- Interspecies Relations in The Little Golden Books. -

ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT

ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 1/84 EO PT No. ICC-01/09-02/11 21-4-11 ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT A PROGRESS REPORT TO THE HON. ATTORNEY-GENERAL BY THE TEAM ON UPDATE OF POST ELECTION VIOLENCE RELATED CASES IN WESTERN, NYANZA, CENTRAL, RIFT-VALLEY, EASTERN, COAST AND NAIROBI PROVINCES MARCH, 2011 NAIROBI ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 3/84 EO PT TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER SUBJECT PAGE TRANSMITTAL LETTER IV 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. GENDER BASED VIOLENCE CASES 7 3. WESTERN PROVINCE 24 3. RIFT VALLEY PROVINCE 30 4. NYANZA PROVINCE 47 5. COAST PROVINCE 62 6. NAIROBI PROVINCE 66 7. CENTRAL PROVINCE 69 8. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 70 9. CONCLUSION 73 10. APPENDICES ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 4/84 EO PT APPENDIX (NO.) LIST OF APPENDICES APP. 1A - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1B - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1C - Update on 2007 Post Election Violence offences As at 4th March, 2010 (police commissioner’s report) APP. 1D - Update by Taskforce on Gender Based Violence Cases (police commissioner’s report) APP. 2 - Memo to Solicitor- General from CPP APP. 3 - Letter from PCIO Western APP. 4 - Letter from PCIO Rift Valley APP.5 - Cases Pending Under Investigations in Rift Valley on special interest cases APP.6 - Cases where suspects are known in Rift Valley but have not been arrested APP.7 - Letter from PCIO Nyanza APP.8 - Letter from PCIO Coast APP.9 - Letter from PCIO Nairobi APP.10 - Correspondences from the team ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 5/84 EO PT The Hon. -

Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (Genus: Pongo)- the Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2015 Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-121397 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Mattle-Greminger, Maja Patricia. Unraveling the evolutionary history of Orangutans (genus: Pongo)- the impact of environmental processes and the genomic basis of adaptation. 2015, University of Zurich, Faculty of Science. Unraveling the Evolutionary History of Orangutans (genus: Pongo) — The Impact of Environmental Processes and the Genomic Basis of Adaptation Dissertation zur Erlangung der naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorwürde (Dr. sc. nat.) vorgelegt der Mathematisch‐naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Zürich von Maja Patricia Mattle‐Greminger von Richterswil (ZH) Promotionskomitee Prof. Dr. Carel van Schaik (Vorsitz) PD Dr. Michael Krützen (Leitung der Dissertation) Dr. Maria Anisimova Zürich, 2015 To my family Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 1 Summary ..................................................................................................................... 3 Zusammenfassung ..................................................................................................... -

Duncan Public Library Board of Directors Meeting Minutes June 23, 2020 Location: Duncan Public Library

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: August 25, 2020 Time: 9:30 am Place: Zoom Meeting 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from July 28, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for June. 4. Presentation of library claims for June. Approval. 5. Director’s report a. Summer reading program b. Genealogy Library c. StoryWalk d. Annual report to ODL e. Sept. Library Card Month f. DALC grant for Citizenship Corner g. After-school snack program 6. Consider a list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed books be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 7. Consider approving creation of a Student Library Card and addition of policy to policy manual. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Duncan Public Library Claims for July 1 through 31, 2020 Submitted to Library Board, August 25, 2020 01-11-521400 Materials & Supplies 20-1879 Demco......................................................................................................................... $94.94 Zigzag shelf, children’s 20-2059 Quill .......................................................................................................................... $589.93 Tissue, roll holder, paper, soap 01-11-522800 Phone/Internet 20-2222 AT&T ........................................................................................................................... $41.38 -

Learned Vocal and Breathing Behavior in an Enculturated Gorilla

Anim Cogn (2015) 18:1165–1179 DOI 10.1007/s10071-015-0889-6 ORIGINAL PAPER Learned vocal and breathing behavior in an enculturated gorilla 1 2 Marcus Perlman • Nathaniel Clark Received: 15 December 2014 / Revised: 5 June 2015 / Accepted: 16 June 2015 / Published online: 3 July 2015 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Abstract We describe the repertoire of learned vocal and relatively early into the evolution of language, with some breathing-related behaviors (VBBs) performed by the rudimentary capacity in place at the time of our last enculturated gorilla Koko. We examined a large video common ancestor with great apes. corpus of Koko and observed 439 VBBs spread across 161 bouts. Our analysis shows that Koko exercises voluntary Keywords Breath control Á Gorilla Á Koko Á Multimodal control over the performance of nine distinctive VBBs, communication Á Primate vocalization Á Vocal learning which involve variable coordination of her breathing, lar- ynx, and supralaryngeal articulators like the tongue and lips. Each of these behaviors is performed in the context of Introduction particular manual action routines and gestures. Based on these and other findings, we suggest that vocal learning and Examining the vocal abilities of great apes is crucial to the ability to exercise volitional control over vocalization, understanding the evolution of human language and speech particularly in a multimodal context, might have figured since we diverged from our last common ancestor. Many theories on the origins of language begin with two basic premises concerning the vocal behavior of nonhuman pri- mates, especially the great apes. They assume that (1) apes (and other primates) can exercise only negligible volitional control over the production of sound with their vocal tract, and (2) they are unable to learn novel vocal behaviors beyond their species-typical repertoire (e.g., Arbib et al. -

Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023

Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023 This plan is written in collaboration with various institutions that have interest and are working tirelessly in conserving chimpanzees in Tanzania. Editorial list i. Dr. Edward Kohi ii. Dr. Julius Keyyu iii. Dr. Alexander Lobora iv. Ms. Asanterabi Kweka v. Dr. Iddi Lipembe vi. Dr. Shadrack Kamenya vii. Dr. Lilian Pintea viii. Dr. Deus Mjungu ix. Dr. Nick Salafsky x. Dr. Flora Magige xi. Dr. Alex Piel xii. Ms. Kay Kagaruki xiii. Ms. Blanka Tengia xiv. Mr. Emmanuel Mtiti Published by: Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) Citation: TAWIRI (2018) Tanzania Chimpanzee Conservation Action Plan 2018-2023 TAWIRI Contact: [email protected] Cover page photo: Chimpanzee in Mahale National Park, photo by Simula Maijo Peres ISBN: 978-9987-9567-53 i Acknowledgements On behalf of the Ministry of Natural Resource and Tourism (MNRT), Wildlife Division (WD), Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA), and Tanzania Wildlife Authority (TAWA), the Tanzania Wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI) wishes to express its gratitude to organizations and individuals who contributed to the development of this plan. We acknowledge the financial support from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) for the planning process. Special thanks are extended to the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) and Kyoto University for their long-term chimpanzee research in the country that has enhanced our understanding of the species behaviour, biology and ecology, thereby greatly contributing to the development process of this conservation action plan. TAWIRI also wishes to acknowledge contributions by Conservation Breeding Specialist Group - Species Survival Commission of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Evaluation and Research Technologies for Health, Inc. -

LING 001 Introduction to Linguistics

LING 001 Introduction to Linguistics Lecture #6 Animal Communication 2 02/05/2020 Katie Schuler Announcements • Exam 1 is next class (Monday)! • Remember there are no make-up exams (but your lowest exam score will be dropped) How to do well on the exam • Review the study guides • Make sure you can answer the practice problems • Come on time (exam is 50 minutes) • We MUST leave the room for the next class First two questions are easy Last time • Communication is everywhere in the animal kingdom! • Human language is • An unbounded discrete combinatorial system • Many animals have elements of this: • Honeybees, songbirds, primates • But none quite have language Case Study #4: Can Apes learn Language? Ape Projects • Viki (oral production) • Sign Language: • Washoe (Gardiner) (chimp) • Nim Chimpsky (Terrace) (chimp) • Koko (Patterson) (gorilla) • Kanzi (Savage-Rumbaugh) (bonobo) Viki’s `speech’ • Raised by psychologists • Tried to teach her oral language, but didn’t get far... Later Attempts • Later attempts used non-oral languages — • either symbols (Sarah, Kanzi) or • ASL (Washoe, Koko, Nim). • Extensive direct instruction by humans. • Many problems of interpretation and evaluation. Main one: is this a • miniature/incipient unbounded discrete combinatorial system, or • is it just rote learning+randomness? Washoe and Koko Video Washoe • A chimp who was extensively trained to use ASL by the Gardners • Knew 132 signs by age 5, and over 250 by the end of her life. • Showed some productive use (‘water bird’) • And even taught her adopted son Loulis some signs But the only deaf, native signer on the team • ‘Every time the chimp made a sign, we were supposed to write it down in the log… They were always complaining because my log didn’t show enough signs. -

Unit 5/Week 4 Title: Koko's Kitten Suggested Time

McGraw-Hill Open Court - 2002 Grade 4 Unit 5/Week 4 Title: Koko’s Kitten Suggested Time: 5 days (45 minutes per day) Common Core ELA Standards: RI.4.1, RI.4.2, RI.4.3, RI.4.4; RF.4.4; W.4.2, W.4.4, W.4.7, W.4.9; SL.4.1; L.4.1, L.4.2, L.4.4 Teacher Instructions Refer to the Introduction for further details. Before Teaching 1. Read the Big Ideas and Key Understandings and the Synopsis. Please do not read this to the students. This is a description for teachers, about the big ideas and key understanding that students should take away after completing this task. Big Ideas and Key Understandings Animals are capable of experiencing the same feelings as human beings; desire, disappointment, love, nurturing, and sadness. They are also capable of making important connections with other living things. Synopsis Koko’s Kitten is the story of Koko, a gorilla, who longs to have a kitten as her “baby.” Koko is able to communicate her feelings to her trainer, Dr. Patterson and the assistants through sign language. After some time, she gets her kitten. Koko treats the kitten as her baby and loves and nurtures him. The kitten grows and one day gets hit by a car. This event upsets Koko but after some time, Koko gets another kitten to love and care for. 2. Read entire main selection text, keeping in mind the Big Ideas and Key Understandings. 3. Re-read the main selection text while noting the stopping points for the Text Dependent Questions and teaching Vocabulary.