Wildlife Rights and Human Obligations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PASA 2005 Final Report.Pdf

PAN AFRICAN SANCTUARY ALLIANCE 2005 MANAGEMENT WORKSHOP REPORT 4-8 June 2005 Mount Kenya Safari Lodge, Nanyuki, Kenya Hosted by Pan African Sanctuary Alliance / Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary Photos provided by Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary – Sierra Leone (cover), PASA member sanctuaries, and Doug Cress. A contribution of the World Conservation Union, Species Survival Commission, Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG) and Primate Specialist Group (PSG). © Copyright 2005 by CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Prepared by participants in the PASA 2005 Management Workshop, Mount Kenya, Kenya, 4th – 8th June 2005 W. Mills, D. Cress, & N. Rosen (Editors). Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (SSC/IUCN). 2005. Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report. Additional copies of the Pan African Sanctuary Alliance (PASA) 2005 Workshop Report can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation -

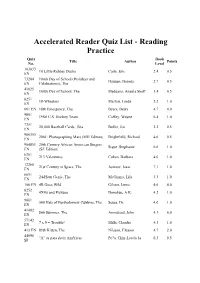

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Animals and the Frontiers of Citizenship

Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 34, No. 2 (2014), pp. 201–219 doi:10.1093/ojls/gqu001 Published Advance Access February 5, 2014 Animals and the Frontiers of Citizenship Will Kymlicka* and Sue Donaldson** Abstract —Citizenship has been at the core of struggles by historically excluded Downloaded from groups for respect and inclusion. Can citizenship be extended even further to domesticated animals? We begin this article by sketching an argument for why justice requires the extension of citizenship to domesticated animals, above and beyond compassionate care, stewardship or universal basic rights. We then consider two objections to this argument. Some animal rights theorists worry that extending citizenship to domesticated animals, while it may sound progressive, would in fact http://ojls.oxfordjournals.org/ be bad for animals, providing yet another basis for policing their behaviour to fit human needs and interests. Critics of animal rights, on the other hand, worry that the inclusion of ‘unruly’ beasts would be bad for democracy, eroding its core values and principles. We attempt to show that both objections are misplaced, and that animal citizenship would both promote justice for animals and deepen fundamental democratic dispositions and values. Keywords: citizenship, animal rights, justice, co-operation at Queen's University on June 23, 2014 1. Introduction In our recent book Zoopolis, we made the case for a distinctly ‘political theory of animal rights’.1 In this Lecture, we attempt to extend that argument, and to respond to some critics of it, by focusing specifically on the novel idea of ‘animal citizenship’. To begin, let us briefly situate our approach in the larger animal rights debate. -

Sensocentrismo.-Ciencia-Y-Ética.Pdf

SENSOCENTRISMO CIENCIA Y ÉTICA Edición: 14/08/2018 “La experiencia viene a demostrarnos, desgraciadamente, cuán largo tiempo transcurrió antes de que miráramos como semejantes a los hombres que difieren considerablemente de nosotros por su apariencia y por sus hábitos. Una de las últimas adquisiciones morales parece ser la simpatía, extendiéndose más allá de los límites de la humanidad. [...] Esta virtud, una de las más nobles con que el hombre está dotado, parece surgir incidentalmente de nuestras simpatías volviéndose más sensibles y más ampliamente difundidas, hasta que se extienden a todos los seres sintientes.” — Charles Robert Darwin - 1 - Agradecimientos Agradezco la influencia inspiradora que me brindaron a largo de la conformación del libro a Jeremías, Carlos, Pedro, Ricardo, Steven, Jesús (el filósofo, no el carpintero), Carl e Isaac. Como así también la contribución intelectual y el apoyo de Iván, David, Facundo, María B., María F., Damián, Gonzalo y tantos otros. - 2 - Prólogo Como su tapa lo indica, este es un libro sobre sensocentrismo, la consideración moral centrada en la sintiencia. Para empezar, deberemos tratar la mente, conduciéndonos a la evolución. Hace 600 millones de años aparecen las mentes en nuestro planeta. Hasta antes no había nadie al que le importara, sufriera o disfrutara, lo que sucedía, no había «punto de vista», ni emoción ni cognición. Hace 2 millones de años, un linaje de monos originarios de África comenzaría gradualmente a comunicarse oralmente, compartir información mediante ondas mecánicas, sonidos, propagables en la atmósfera gaseosa (previamente producida por primitivos organismos fotosintéticos). Adquirirían cultura, información copiándose, sobreviviendo y evolucionando a través de las sucesivas generaciones parlanchinas, desde la prehistoria, y luego también escritoras. -

Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 With an Open Heart: Folia De Reis, a Brazilian Spiritual Journey Through Song Welson Alves Tremura Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC WITH AN OPEN HEART: FOLIA DE REIS, A BRAZILIAN SPIRITUAL JOURNEY THROUGH SONG By WELSON ALVES TREMURA A Dissertation submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2004 Copyright 2004 Welson Alves Tremura All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Welson Alves Tremura defended on April 5, 2004. _____________________________ Dale A. Olsen Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Anthony Oliver-Smith Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member _____________________________ Larry Crook Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii The folia de reis high-pitched voices singing in the distance are memories of a childhood of music and celebrations that go back to the early 1970s when playing soccer in a field not larger than a basketball court or flying a kite were the highest point of most children in that part of Brazil. The folia groups could be heard in the distance with the tala or high pitch voice singing the last part of the refrain. These sounds could typically be heard echoing throughout the surrounding neighborhoods of Olímpia, São Paulo during the second half of the month of December and early part of January. -

The Ethical Consistency of Animal Equality

1 The ethical consistency of animal equality Stijn Bruers, Sept 2013, DRAFT 2 Contents 0. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 5 0.1 SUMMARY: TOWARDS A COHERENT THEORY OF ANIMAL EQUALITY ........................................................................ 9 1. PART ONE: ETHICAL CONSISTENCY ......................................................................................................... 18 1.1 THE BASIC ELEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 18 a) The input data: moral intuitions .......................................................................................................... 18 b) The method: rule universalism............................................................................................................. 20 1.2 THE GOAL: CONSISTENCY AND COHERENCE ..................................................................................................... 27 1.3 THE PROBLEM: MORAL ILLUSIONS ................................................................................................................ 30 a) Optical illusions .................................................................................................................................... 30 b) Moral illusions .................................................................................................................................... -

Educational Rights and the Roles of Virtues, Perfectionism, and Cultural Progress

The Law of Education: Educational Rights and the Roles of Virtues, Perfectionism, and Cultural Progress R. GEORGE WRIGHT* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 385 II. EDUCATION: PURPOSES, RECENT OUTCOMES, AND LEGAL MECHANISMS FOR REFORM ................................................................ 391 A. EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES AND RIGHTS LANGUAGE ...................... 391 B. SOME RECENT GROUNDS FOR CONCERN IN FULFILLING EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ............................................................. 393 C. THE BROAD RANGE OF AVAILABLE TECHNIQUES FOR THE LEGAL REFORM OF EDUCATION ............................................................... 395 III. SOME LINKAGES BETWEEN EDUCATION AND THE BASIC VIRTUES, PERFECTIONISM, AND CULTURAL PROGRESS ..................................... 397 IV. VIRTUES AND THEIR LEGITIMATE PROMOTION THROUGH THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM ...................................................................... 401 V. PERFECTIONISM AND ITS LEGITIMATE PROMOTION THROUGH THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM ...................................................................... 410 VI. CULTURAL PROGRESS OVER TIME AND ITS LEGITIMATE PROMOTION THROUGH THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM .............................................. 417 VII. CONCLUSION: EDUCATION LAW AS RIGHTS-CENTERED AND AS THE PURSUIT OF WORTHY VALUES AND GOALS: THE EXAMPLE OF HORNE V. FLORES ............................................................................................ 431 I. INTRODUCTION The law of education -

Reading List for Comprehensive Examination in Political Theory

READING LIST FOR COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION IN POLITICAL THEORY Department of Political Science Columbia University Requirements Majors should prepare for questions based on reading from the entire reading list. Minors should prepare for questions based on reading from the core list and any one of the satellite lists. CORE LIST Plato, The Republic Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics Books I, II, V, VIII, X; Politics Polybius, Rise of the Roman Empire, Book I paragraphs 1-10 (“Introduction”) and Book VI Cicero, The Republic Augustine, City of God, Books I, VIII (ch.s 4-11), XII, XIV, XIX, XXII (ch.s 23-24, 29-30) Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Questions 42, 66, 90-92, 94-97, 105 Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince; Discourses (as selected in Selected Political Writings, ed. David Wootton) Jean Bodin, On Sovereignty (ed. Julian Franklin) Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan (as selected in Norton Critical Edition, ed. David Johnston) James Harrington, Oceana (Cambridge U. Press, ed. J.G.A. Pocock), pp. 63-70 (from Introduction), pp. 161-87; 413-19 John Locke, Second Treatise of Government; “A Letter Concerning Toleration” David Hume, “Of the Original Contract,” “The Independence of Parliament,” “That Politics May Be Reduced to A Science,” “Of the First Principle of Government,” “Of Parties in General” 1 Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws (as selected in Selected Political Writings, ed. Melvin Richter) Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Part I ("On the propriety of action"); Part II, Section II ("Of justice and beneficence"); Part IV ("On the effect of utility on the sentiment of approbation") Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origins of Inequality; On The Social Contract Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (as selected in World’s Classics Edition, ed. -

ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT

ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 1/84 EO PT No. ICC-01/09-02/11 21-4-11 ANNEX 3 ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 2/84 EO PT A PROGRESS REPORT TO THE HON. ATTORNEY-GENERAL BY THE TEAM ON UPDATE OF POST ELECTION VIOLENCE RELATED CASES IN WESTERN, NYANZA, CENTRAL, RIFT-VALLEY, EASTERN, COAST AND NAIROBI PROVINCES MARCH, 2011 NAIROBI ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 3/84 EO PT TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER SUBJECT PAGE TRANSMITTAL LETTER IV 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. GENDER BASED VIOLENCE CASES 7 3. WESTERN PROVINCE 24 3. RIFT VALLEY PROVINCE 30 4. NYANZA PROVINCE 47 5. COAST PROVINCE 62 6. NAIROBI PROVINCE 66 7. CENTRAL PROVINCE 69 8. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 70 9. CONCLUSION 73 10. APPENDICES ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 4/84 EO PT APPENDIX (NO.) LIST OF APPENDICES APP. 1A - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1B - Memo from CPP to Hon. Attorney General APP.1C - Update on 2007 Post Election Violence offences As at 4th March, 2010 (police commissioner’s report) APP. 1D - Update by Taskforce on Gender Based Violence Cases (police commissioner’s report) APP. 2 - Memo to Solicitor- General from CPP APP. 3 - Letter from PCIO Western APP. 4 - Letter from PCIO Rift Valley APP.5 - Cases Pending Under Investigations in Rift Valley on special interest cases APP.6 - Cases where suspects are known in Rift Valley but have not been arrested APP.7 - Letter from PCIO Nyanza APP.8 - Letter from PCIO Coast APP.9 - Letter from PCIO Nairobi APP.10 - Correspondences from the team ICC-01/09-02/11-67-Anx3 21-04-2011 5/84 EO PT The Hon. -

REID-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf

VEGANISM AND THE ETHICS AND EPISTEMOLOGY OF DISAGREEMENT: A NEO-PASCALIAN APPROACH By Adam Curran Reid, B.A., M.A. A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland, February, 2018 © Adam Curran Reid 2018 All Rights Reserved Abstract Disagreement is without a doubt one of the most universal, enduring, and oftentimes quite vexing, features of our life in common. This latter aspect, to be sure, becomes all the more evident when the particular disagreement at hand concerns differing ethical beliefs, value-judgments, or deep questions about the nature, and scope, of morally permissible action as such. One such question—also the chief subject of dispute to be taken up in this dissertation—is whether or not human beings are morally justified in killing, eating, wearing—in a word, exploiting—non-human animals for our benefit when doing so is neither required for us to survive or to flourish. Ethical vegans answer ‘no,’ insisting that non-human animals, qua sentient, conscious, experiential selves, ought to be treated with fundamental concern and respect, which, at a minimum, demands that we stop exploiting them as resources and commodities. Unsurprisingly, many disagree. While I shall have much more to say about (and in support for) ethical veganism in what follows, the guiding aim of this dissertation is firstly to explore certain key questions regarding the ethics and epistemology of disagreement(s) about veganism. In this way, my approach notably departs from that which has long prevailed (and rightly so) in conventional animal rights theory and vegan advocacy, where the emphasis, and aim, has generally been about making the first-order case for animal rights, abolition, and, therein, for veganism itself. -

The Case for Not Being Born the Antinatalist Philosopher David

The Case for Not Being Born The antinatalist philosopher David Benatar argues that it would be better if no one had children ever again. By Joshua Rothman November 27, 2017 David Benatar may be the world’s most pessimistic philosopher. An “antinatalist,” he believes that life is so bad, so painful, that human beings should stop having children for reasons of compassion. “While good people go to great lengths to spare their children from suffering, few of them seem to notice that the one (and only) guaranteed way to prevent all the suffering of their children is not to bring those children into existence in the first place,” he writes, in a 2006 book called “Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming Into Existence.” In Benatar’s view, reproducing is intrinsically cruel and irresponsible—not just because a horrible fate can befall anyone, but because life itself is “permeated by badness.” In part for this reason, he thinks that the world would be a better place if sentient life disappeared altogether. For a work of academic philosophy, “Better Never to Have Been” has found an unusually wide audience. It has 3.9 stars on GoodReads, where one reviewer calls it “required reading for folks who believe that procreation is justified.” A few years ago, Nic Pizzolatto, the screenwriter behind “True Detective,” read the book and made Rust Cohle, Matthew McConaughey’s character, a nihilistic antinatalist. (“I think human consciousness is a tragic misstep in evolution,” Cohle says.) When Pizzolatto mentioned the book to the press, Benatar, who sees his own views as more thoughtful and humane than Cohle’s, emerged from an otherwise reclusive life to clarify them in interviews. -

Critical Guide to Mill's on Liberty

This page intentionally left blank MILL’S ON LIBERTY John Stuart Mill’s essay On Liberty, published in 1859, has had a powerful impact on philosophical and political debates ever since its first appearance. This volume of newly commissioned essays covers the whole range of problems raised in and by the essay, including the concept of liberty, the toleration of diversity, freedom of expression, the value of allowing “experiments in living,” the basis of individual liberty, multiculturalism, and the claims of minority cultural groups. Mill’s views have been fiercely contested, and they are at the center of many contemporary debates. The essays are by leading scholars, who systematically and eloquently explore Mill’s views from various per spectives. The volume will appeal to a wide range of readers including those interested in political philosophy and the history of ideas. c. l. ten is Professor of Philosophy at the National University of Singapore. His publications include Was Mill a Liberal? (2004) and Multiculturalism and the Value of Diversity (2004). cambridge critical guides Volumes published in the series thus far: Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit edited by dean moyar and michael quante Mill’s On Liberty edited by c. l. ten MILL’S On Liberty A Critical Guide edited by C. L. TEN National University of Singapore CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521873567 © Cambridge University Press 2008 This publication is in copyright.