Unwatched Trains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Term Care for Seniors at 640 Lansdowne Avenue

EX3.6 REPORT FOR ACTION Creating New Affordable Rental Homes and Long- Term Care For Seniors at 640 Lansdowne Avenue Date: March 12, 2019 To: Executive Committee From: Deputy City Manager, Community and Social Services & Deputy City Manager, Corporate Services Wards: Ward 9 - Davenport SUMMARY The number of people in Toronto aged 65 and over is expected to almost double by 2041. This growing population of seniors will spur a demand for more affordable housing as well as long-term care homes to be developed specifically to address the evolving needs of seniors in our city. In recognition of the growing urgency to provide both affordable rental and long-term care homes for seniors, at its meeting on May 22, 23 and 24, 2018, City Council requested the Director, Affordable Housing Office, in consultation with CreateTO, to include the opportunity for development of long-term care beds within the affordable housing development planned for a portion of the Toronto Transit Commission property at 640 Lansdowne Avenue. On August 2, 2018, CreateTO, on behalf of the Affordable Housing Office, issued a Request for Proposals ("RFP") for Developing and Operating Affordable Housing Services at 640 Lansdowne Avenue. The RFP offered the one-third, Mixed Use designated portion of the site under a lease arrangement for 99 years at nominal rent to stimulate development of the site and ensure long-term affordability for seniors. The RFP closed on September 6, 2018 and four submissions were received. Since September 2018, CreateTO and City staff have been in discussions with Magellan Community Charities, the proposed proponent, and this report recommends that the City enter into a Letter of Intent ("LOI"), outlining the terms and conditions of the lease and the City's Open Door incentives being provided for the up to 65 affordable rental homes being proposed. -

Toronto Subway System, ON

Canadian Geotechnical Society Canadian Geotechnical Achievements 2017 Toronto Subway System Geotechnical Investigation and Design of Tunnels Geographical location Key References Wong, JW. 1981. Geotechnical/ Toronto, Ontario geological aspects of the Toronto subway system. Toronto Transit Commission. When it began or was completed Walters, DL, Main, A, Palmer, S, Construction began in 1949 and continues today. Westland, J, and Bihendi, H. 2011. Managing subsurface risk for Toronto- York Spadina Subway extension project. Why a Canadian geotechnical achievement? 2011 Pan-Am and CGS Geotechnical Conference. Construction of the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) subway system, the first in Canada, began in 1949 and currently consists Photograph and Map of four subway lines. In total there are currently approximately 68 km of subway tracks and 69 stations. Over one million trips are taken daily on the TTC during weekdays. The subway system has been expanded in several stages, from 1954, when the first line (the Yonge Line) was opened, to 2002, when the most recently completed line (the Sheppard Line) was opened. Currently the Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension is under construction. The subway tunnels have been constructed using a number of different technologies over the years including: open cut excavation, open/closed shield tunneling under ambient air pressure and compressed air, hand mining and earth pressurized tunnel boring machines. The subway tunnels range in design from reinforced concrete box structures to approximately 6 m diameter precast concrete segmental liners or cast iron segmental liners. Looking east inside newly constructed TTC subway The tunnels have been advanced through various geological tunnel, 1968. (City of Toronto Archives) formations: from hard glacial tills to saturated alluvial sands and silts, and from glaciolacustrine clays to shale bedrock. -

Historical Outlines of Railways in Southwestern Ontario

UCRS Newsletter • July 1990 Toronto & Guelph Railway Note: The Toronto & Goderich Railway Company was estab- At the time of publication of this summary, Pat lished in 1848 to build from Toronto to Guelph, and on Scrimgeour was on the editorial staff of the Upper to Goderich, on Lake Huron. The Toronto & Guelph Canada Railway Society (UCRS) newsletter. This doc- was incorporated in 1851 to succeed the Toronto & ument is a most useful summary of the many pioneer Goderich with powers to build a line only as far as Guelph. lines that criss-crossed south-western Ontario in the th th The Toronto & Guelph was amalgamated with five 19 and early 20 centuries. other railway companies in 1854 to form the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada. The GTR opened the T&G line in 1856. 32 - Historical Outlines of Railways Grand Trunk Railway Company of Canada in Southwestern Ontario The Grand Trunk was incorporated in 1852 with au- BY PAT SCRIMGEOUR thority to build a line from Montreal to Toronto, assum- ing the rights of the Montreal & Kingston Railway Company and the Kingston & Toronto Railway Com- The following items are brief histories of the railway pany, and with authority to unite small railway compa- companies in the area between Toronto and London. nies to build a main trunk line. To this end, the follow- Only the railways built in or connecting into the area ing companies were amalgamated with the GTR in are shown on the map below, and connecting lines in 1853 and 1854: the Grand Trunk Railway Company of Toronto, Hamilton; and London are not included. -

Rapid Transit in Toronto Levyrapidtransit.Ca TABLE of CONTENTS

The Neptis Foundation has collaborated with Edward J. Levy to publish this history of rapid transit proposals for the City of Toronto. Given Neptis’s focus on regional issues, we have supported Levy’s work because it demon- strates clearly that regional rapid transit cannot function eff ectively without a well-designed network at the core of the region. Toronto does not yet have such a network, as you will discover through the maps and historical photographs in this interactive web-book. We hope the material will contribute to ongoing debates on the need to create such a network. This web-book would not been produced without the vital eff orts of Philippa Campsie and Brent Gilliard, who have worked with Mr. Levy over two years to organize, edit, and present the volumes of text and illustrations. 1 Rapid Transit in Toronto levyrapidtransit.ca TABLE OF CONTENTS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 About this Book 9 Edward J. Levy 11 A Note from the Neptis Foundation 13 Author’s Note 16 Author’s Guiding Principle: The Need for a Network 18 Executive Summary 24 PART ONE: EARLY PLANNING FOR RAPID TRANSIT 1909 – 1945 CHAPTER 1: THE BEGINNING OF RAPID TRANSIT PLANNING IN TORONTO 25 1.0 Summary 26 1.1 The Story Begins 29 1.2 The First Subway Proposal 32 1.3 The Jacobs & Davies Report: Prescient but Premature 34 1.4 Putting the Proposal in Context CHAPTER 2: “The Rapid Transit System of the Future” and a Look Ahead, 1911 – 1913 36 2.0 Summary 37 2.1 The Evolving Vision, 1911 40 2.2 The Arnold Report: The Subway Alternative, 1912 44 2.3 Crossing the Valley CHAPTER 3: R.C. -

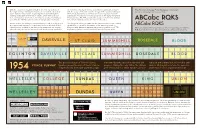

TTC Typography History

With the exception of Eglinton Station, 11 of the 12 stations of The intention of using Helvetica and Univers is unknown, however The Toronto Subway Font (Designer Unknown) the original Yonge Subway line have been renovated extensively. with the usage of the latter on the design of the Spadina Subway in Based on Futura by Paul Renner (1928) Some stations retained the original typefaces but with tighter 1978, it may have been an internal decision to try and assimilate tracking and subtle differences in weight, while other stations subsequent renovations of existing stations in the aging Yonge and were renovated so poorly there no longer is a sense of simplicity University lines. The TTC avoided the usage of the Toronto Subway seen with the 1954 designs in terms of typographical harmony. font on new subway stations for over two decades. ABCabc RQKS Queen Station, for example, used Helvetica (LT Std 75 Bold) in such The Sheppard Subway in 2002 saw the return of the Toronto Subway an irresponsible manner; it is repulsively inconsistent with all the typeface as it is used for the names of the stations posted on ABCabc RQKS other stations, and due to the renovators preserving the original platfrom level. Helvetica became the primary typeface for all TTC There are subtle differences between the two typefaces, notably the glass tile trim, the font weight itself looks botched and unsuitable. wayfinding signages and informational material system-wide. R, Q, K, and S; most have different terminals, spines, and junctions. ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL BLOOR DANGER DA N GER Danger DO NOT ENTER Do Not Enter Do Not Enter DAVISVILLE ST CL AIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR EGLINTON DAVISVILLE ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR EGLINTON DAVISVILLE ST CLAIR SUMMERHILL ROSEDALE BLOOR The specially-designed Toronto Subway that embodied the spirit of modernism and replaced with a brutal mix of Helvetica and YONGE SUBWAY typeface graced the walls of the 12 stations, progress. -

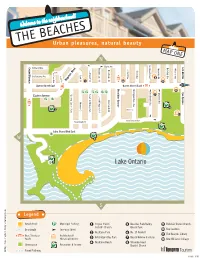

90Ab-The-Beaches-Route-Map.Pdf

THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP ONE N Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Coxw Dixon Ave Bell Brookmount Rd Wheeler Ave Wheeler Waverley Rd Waverley Ashland Ave Herbert Ave Boardwalk Dr Lockwood Rd Elmer Ave efair Ave efair O r c h ell A ell a r d Lark St Park Blvd Penny Ln venu Battenberg Ave 8 ingston Road K e 1 6 9 Queen Street East Queen Street East Woodbine Avenue 11 Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Kippendavie Ave Kippendavie Ave Waverley Rd Waverley Sarah Ashbridge Ave Northen Dancer Blvd Eastern Avenue Joseph Duggan Rd 7 Boardwalk Dr Winners Cir 10 2 Buller Ave V 12 Boardwalk Dr Kew Beach Ave Al 5 Lake Shore Blvd East W 4 3 Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking Corpus Christi Beaches Park/Balmy Bellefair United Church g 1 5 9 Catholic Church Beach Park 10 Kew Gardens . Desi Boardwalk One-way Street d 2 Woodbine Park 6 No. 17 Firehall her 11 The Beaches Library p Bus, Streetcar Architectural/ he Ashbridge’s Bay Park Beach Hebrew Institute S 3 7 Route Historical Interest 12 Kew Williams Cottage 4 Woodbine Beach 8 Waverley Road : Diana Greenspace Recreation & Leisure g Baptist Church Writin Paved Pathway BEACH_0106 THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP TWO N H W Victoria Park Avenue Nevi a S ineva m Spruc ca Lee Avenue Kin b Wheeler Ave Wheeler Balsam Ave ly ll rbo Beech Ave Willow Ave Av Ave e P e Crown Park Rd gs Gle e Hill e r Isleworth Ave w o ark ark ug n Manor Dr o o d R d h R h Rd Apricot Ln Ed Evans Ln Blvd Duart Park Rd d d d 15 16 18 Queen Street East 11 19 Balsam Ave Beech Ave Willow Ave Leuty Ave Nevi Hammersmith Ave Hammersmith Ave Scarboro Beach Blvd Maclean Ave N Lee Avenue Wineva Ave Glen Manor Dr Silver Birch Ave Munro Park Ave u Avion Ave Hazel Ave r sew ll Fernwood Park Ave Balmy Ave e P 20 ood R ark ark Bonfield Ave Blvd d 0 Park Ave Glenfern Ave Violet Ave Selwood Ave Fir Ave 17 12 Hubbard Blvd Silver Birch Ave Alfresco Lawn 14 13 E Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking g 13 Leuty Lifesaving Station 17 Balmy Beach Club . -

Relief Line Update

Relief Line Update Mathieu Goetzke, Vice-President, Planning David Phalp, Manager, Rapid Transit Planning FEBRUARY 7, 2019 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • The Relief Line South alignment identified by the City of Toronto as preferred, has a Benefit Cost Ratio (BCR) above 1.0, demonstrating the project’s value; however, since it is close to 1.0, it is highly sensitive to costs, so more detailed design work and procurement method choice will be of importance to maintain or improve this initial BCR. • Forecasts suggest that Relief Line South will attract ridership to unequivocally justify subway-level service; transit-oriented development opportunities can further boost ridership. • Transit network forecasts show that Relief Line South needs to be in operation before the Yonge North Subway Extension. Relief Line North provides further crowding relief for Line 1. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 2 SUBWAY EXPANSION - PROJECT STATUS Both Relief Line North and South and the Yonge North Subway Extension are priority projects included in the 2041 Regional Transportation Plan. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 3 RELIEF LINE SOUTH: Initial Business Case Alignments Evaluated • Metrolinx is developing an Initial Business Case on Relief Line South, evaluating six alignments according to the Metrolinx Business Case Guidance and the Auditor General’s 2018 recommendations • Toronto City Council approved the advancement of alignment “A” (Pape- Queen via Carlaw & Eastern) • Statement of Completion of the Transit Project Assessment Process (TPAP) received October 24, 2018. RELIEF LINE UPDATE 4 RELIEF -

Canadian Rail No189 1967

_il'-.......II ....... D. m~nn No.189 June 1967 ~A CBHA~ C@ M:lLBSTONB ~ info from E.M. Johnson = '§:. Ii) e G~ !, ur cover photograph and the two pictures on the opposite page record a truly historic event for the Canadian Railroad His torical Association -- the first operation of a "museum" locomotive under steam. This very worthy centennial activity has been carried out by our EDMONTON CHAPTER, notwithstanding very limited material resources. As mentioned in an earlier "Canadian Rail", Northern Alberta 2-8-0 No. 73 was moved outside of the Cromdale carbarns of the Edmonton Transit System before Christmas 1966, but this was by filling the boiler with air pressure at 100 pounds per inch squared. This provided sufficient energy to move the locomotive in and out of the barns and served as a cold test of the restored engine's pipes and valves. Recently, the Edmonton Chapter obtained an Alberta Pro vincial boiler inspection certificate and the engine was steamed for the first time since being donated to the Association, on April 29. The accompanying photos were taken on April 30. The engine is in fine condition and reflects great credit on the Edmonton team, led by Harold Maw, which has worked long and hard on the restoration project. One stall of the Cromdale carbarns, now used for buses, has been made available to the C.R.H.A. and houses Edmonton street car No. I, Locomotive No. 73, and other smaller items such as handcars. The carbarns are located immediately alongside the CN's main line leading to the downtown passenger station and are served by a railway spur. -

Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register -1627 Danforth Avenue

~TORONTO REPORT FOR ACTION Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register - 1627 Danforth Avenue Date: April 4, 2019 To: Toronto Preservation Board Toronto and East York Community Council From: Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, Urban Design, City Planning Wards: Ward 19 – Beaches-East York SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council include the property at 1627 Danforth Avenue on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register. The site contains a complex known historically as the Danforth Carhouse, which is currently owned by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). It was developed beginning in 1914 by the Toronto Civic Railways (TCR), expanded by the Toronto Transportation Commission (forerunner to today's TTC) and the TTC and currently used as offices and staff facilities for TTC personnel. In 2015, City Council requested that the property at 1627 Danforth Avenue be researched and evaluated for inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register. It has been identified for its potential cultural heritage value in the Danforth Avenue Planning Study (2018). It is the selected site for a police station consolidating 54 and 55 Divisions. The property at 1627 Danforth Avenue is part of a Master Plan study being undertaken by CreateTO to guide the redevelopment of the site as a multi-use civic hub for the Toronto Transit Commission, the Toronto Police Service and the Toronto Public Library as the key anchor tenants, which will incorporate and adaptively reuse the Danforth Carhouse. RECOMMENDATIONS The Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, Urban Design City Planning recommends that: 1. City Council include the property at 1627 Danforth Avenue on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register in accordance with the Statement of Significance (Reasons for Inclusion), attached as Attachment 3 to the report (April 4, 2019) from the Senior Manager, Heritage Preservation Services, Urban Design, City Planning. -

Rapid Transit on Sheppard Avenue East

Rapid Transit on Sheppard Avenue East Expert Panel Meeting February 17, 2012 TTC Ridership Profile • 58% are female • 41% have no driver’s licence • 34% have no vehicle in the household • 66% are employed • 32% are students • 43% live in an apartment/condominium Importance of Transit to Cities • increase City’s competitive (World Bank, OECD, FCM, UN) stimulate economic growth, attract business • generate, support employment • provide accessibility for mobility impaired • reduce automobile congestion, costs • reduce pollution, improve air quality • influence land uses, create moreefficient city Ridership Growth Strategy Peak Service Improvements Ridership Growth Strategy Additional Off-Peak Service Planning Fundamentals - I Transportation ↔ Land Use land use, density creates travel demand determines required transportation service transportation service / investment improves access to land increases land value shapes land use, density, development Planning Fundamentals - II Demand ↔ Capacity travel demand determines required capacity plus room for growth choice of appropriate transit type Metropolitan Toronto Transportation Plan Review (1975) sample alternative Accelerated Rapid Transit Study (1982) GO Advanced Light Rail Transit (1983) Network 2011 (1986) Let’s Move (1990) Network 2011 / Let’s Move • 1994 – groundbreaking for Eglinton, Sheppard Subways •1995 – Eglinton Subway stopped, filledin •1996 – Sheppard Subway shortened to Don Mills •1996 – Spadina Subway extended one stop to Downsview Network 2011 / Let’s Move What Was -

Annual Report 1986

REPORT A COMMITMENT TO EXCELLENCE TORONTO TRANSIT COMMISSION TABLE 0 F CONTENTS Letter from the Commission 2 Letter from TTC Management 3 A Commitment to Excellence 4 Serving the Public 6 Operating and Maintaining 10 the System Planning for the Future 12 Financial Overview 14 Revenue 16 Expenses 17 Expenses by Function 18 Capital Expenditures 19 Financing 20 Financial Statements December 31, 1986 21 Statement of Revenue and Expenses 21 Balance Sheet 22 Cover: Driver Bill Gorry. a 16-year Statement of Changes 23 veteran with the TTC. in Financial Position Notes to Financial Statements 24 10-Year Financial and Operating Statistics 26 TTC Management Directory 28 LETTER FROM THE COMMISSION o: Mr. Dennis Flynn, (Presidents' Conference Committee) cars, Chairman, and Councillors of the Municipal which have served our patrons well for many ity of Metropolitan Toronto years. One hundred and twenty-six new air conditioned subway cars will also enter ser vice in 1987 and 1988. These new vehicles represent the TTC's commitment to constant LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: renewal of the system to ensure the highest Julian Porter, QC I am proud to present the 1986 Annual standards of service and safety. !Chairman) Report of the Toronto Transit Commission. Throughout its 65-year history the TTC has It has been an award-winning year. The always been able to blend the best of the past TTC's years of planning, building, operating with the technology of the present and the and maintaining the system to provide the ideas of the future. This past is prologue to a best possible service to riders were rewarded challenging future that will call upon the with five major honours, including the Out TTC's considerable experience as important standing Achievement Award given by the decisions approach on transportation priori American Public Transit Association. -

Canadian Rail No280 1975

No. 280 Ma y 1975 POWER lor the People Text Photographs B.A. Biglow J.J.Shaughnessy oU could say that Canadian National Railways were a little late in die selizing their pass~nger trains.The Y steam engine was quite economical for the tonnages and speeds prevalent at that time and thus the multipur pose steam power was retained for passenger trains and was also avail able for freight services, in emer gencies. The diesel locomotive models designed exclusively for passenger trains, such as the Es and PAs, were avoided, since the passenger version of the 4-axle freight units had been developed when CN be gan passenger train dieselization. Canadian National further avoided large numbers of carbody- style units by using hood-type road-switchers on secondary branch lines. For mainline trains, the Company bought FP 9 models from Gen eral Motors Diesel Limited of London, Ontario and FPA 2 and FPA 4 mo dels from Montreal Locomotive Works of Montr'al, Canada. After almost twenty' years, only one true FPA 2 unit survives,it being on the St-Hilaire/Montr'al, Qu'bec commuter run, Trains 900/991. This unit wos built with a model 244 prime mover, which model Can adian National found to be unreliable due to water leaks. Four other units, Numbers 6758, 6759, 6658 and 6659 had the model 244 prime movers removed and the model 251 installed, making them equivalent to the FPA 4 model. The prime-mover/generator assemblies removed from these units were used to "re-manufacture" the four units of the RSC 24 model, CN unit Numbers 1800, 1801, 1802 and 1803, rated at 1400 hp., of which there are three surviving today.