Access to Space ~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of Space Law

THE EMERGENCE OF SPACE LAW Steve Doyle* I. INTRODUCTION Space law exists today as a widely regarded, separate field of jurisprudence; however, it has many overlapping features involving other fields, including international law, contract law, tort law, and administrative law, among others.1 Development of space law concepts began early in the twentieth century and blossomed during the second half of the century into its present state. It is not yet widely taught in law schools, but space law is gradually being accorded more space in law school curricula. Substantial notional law and concepts of space law emerged prior to the first orbiting of a man made satellite named Sputnik in 1957. During the next decade (1958-1967), an intense effort was made to bring law into compliance with the realities of expanding spaceflight activities. During the 1960s, numerous national and international regulatory laws emerged to deal with satellite launches and space radio uses and to ensure greater international awareness and governmental presence in the oversight of ongoing activities in space. Just as gradually developed bodies of maritime law emerged to regulate the operation of global shipping, aeronautical law emerged to regulate the expansion of global civil aviation, and telecommunication law emerged to regulate the global uses of radio and wire communication systems, a new body of law is emerging to regulate the activities of nations in astronautics. We know that new body of law as Space Law. * Stephen E. Doyle is Honorary Director, International Institute of Space Law, Paris. Mr. Doyle worked fifteen years in federal civil service (1966-1981), fifteen years in the aerospace industry (1981-1996), and fifteen years in the power production industry (1996-2012). -

The Flight to Orbit

There are numerous ways to get there— Around the Corner Th As then–US Space Command chief from rocket The Gen. Howell M. Estes III said to launch to space defense writers just before his re- tirement in August, “This is going maneuver to come along a lot quicker than we vehicles—and the think it is. ... We tend to think this stuff is way out there in the future, Air Force is but it’s right around the corner.” keeping its Flight The Air Force and NASA have divided the task of providing the options open. US government with a means of reliable, low-cost transportation to Earth orbit. The Air Force, with the largest immediate need, is heading to up the effort to revamp the Expend- to able Launch Vehicles now used to loft military and other government satellites. Called the Evolved ELV, this program is focused on derivatives of existing rockets. Competitors have been invited to redesign or value- engineer their proven boosters with new materials and technologies to provide reliable launch services at a he Air Force would like to go Orbit far lower price than today’s bench- back and forth to Earth orbit as bit mark of around $10,000 a pound to T O easily as it goes back and forth to Low Earth Orbit. The reasoning is 30,000 feet—routinely, reliably, and that an “evolved”—rather than an relatively cheaply. Such a capability all-new—vehicle will yield cost sav- goes hand in hand with being a true ings while reducing technical risk. -

The SKYLON Spaceplane

The SKYLON Spaceplane Borg K.⇤ and Matula E.⇤ University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, 80309, USA This report outlines the major technical aspects of the SKYLON spaceplane as a final project for the ASEN 5053 class. The SKYLON spaceplane is designed as a single stage to orbit vehicle capable of lifting 15 mT to LEO from a 5.5 km runway and returning to land at the same location. It is powered by a unique engine design that combines an air- breathing and rocket mode into a single engine. This is achieved through the use of a novel lightweight heat exchanger that has been demonstrated on a reduced scale. The program has received funding from the UK government and ESA to build a full scale prototype of the engine as it’s next step. The project is technically feasible but will need to overcome some manufacturing issues and high start-up costs. This report is not intended for publication or commercial use. Nomenclature SSTO Single Stage To Orbit REL Reaction Engines Ltd UK United Kingdom LEO Low Earth Orbit SABRE Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine SOMA SKYLON Orbital Maneuvering Assembly HOTOL Horizontal Take-O↵and Landing NASP National Aerospace Program GT OW Gross Take-O↵Weight MECO Main Engine Cut-O↵ LACE Liquid Air Cooled Engine RCS Reaction Control System MLI Multi-Layer Insulation mT Tonne I. Introduction The SKYLON spaceplane is a single stage to orbit concept vehicle being developed by Reaction Engines Ltd in the United Kingdom. It is designed to take o↵and land on a runway delivering 15 mT of payload into LEO, in the current D-1 configuration. -

Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts: Vehicles, Technologies and Spaceports

Commercial Space Transportation 2006 Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts: Vehicles, Technologies and Spaceports January 2006 HQ003606.INDD 2006 U.S. Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts About FAA/AST About the Office of Commercial Space Transportation The Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA/AST) licenses and regulates U.S. commercial space launch and reentry activity, as well as the operation of non-federal launch and reentry sites, as authorized by Executive Order 12465 and Title 49 United States Code, Subtitle IX, Chapter 701 (formerly the Commercial Space Launch Act). FAA/AST’s mission is to ensure public health and safety and the safety of property while protecting the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States during commercial launch and reentry operations. In addition, FAA/AST is directed to encour- age, facilitate, and promote commercial space launches and reentries. Additional information concerning commercial space transportation can be found on FAA/AST’s web site at http://ast.faa.gov. Federal Aviation Administration Office of Commercial Space Transportation i About FAA/AST 2006 U.S. Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts NOTICE Use of trade names or names of manufacturers in this document does not constitute an official endorsement of such products or manufacturers, either expressed or implied, by the Federal Aviation Administration. ii Federal Aviation Administration Office of Commercial Space Transportation 2006 U.S. Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts Contents Table of Contents Introduction . .1 Significant 2005 Events . .4 Space Competitions . .6 Expendable Launch Vehicles . .9 Current Expendable Launch Vehicle Systems . .9 Atlas 5 - Lockheed Martin Corporation . -

L AUNCH SYSTEMS Databk7 Collected.Book Page 18 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM Databk7 Collected.Book Page 19 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM

databk7_collected.book Page 17 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM CHAPTER TWO L AUNCH SYSTEMS databk7_collected.book Page 18 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM databk7_collected.book Page 19 Monday, September 14, 2009 2:53 PM CHAPTER TWO L AUNCH SYSTEMS Introduction Launch systems provide access to space, necessary for the majority of NASA’s activities. During the decade from 1989–1998, NASA used two types of launch systems, one consisting of several families of expendable launch vehicles (ELV) and the second consisting of the world’s only partially reusable launch system—the Space Shuttle. A significant challenge NASA faced during the decade was the development of technologies needed to design and implement a new reusable launch system that would prove less expensive than the Shuttle. Although some attempts seemed promising, none succeeded. This chapter addresses most subjects relating to access to space and space transportation. It discusses and describes ELVs, the Space Shuttle in its launch vehicle function, and NASA’s attempts to develop new launch systems. Tables relating to each launch vehicle’s characteristics are included. The other functions of the Space Shuttle—as a scientific laboratory, staging area for repair missions, and a prime element of the Space Station program—are discussed in the next chapter, Human Spaceflight. This chapter also provides a brief review of launch systems in the past decade, an overview of policy relating to launch systems, a summary of the management of NASA’s launch systems programs, and tables of funding data. The Last Decade Reviewed (1979–1988) From 1979 through 1988, NASA used families of ELVs that had seen service during the previous decade. -

Quest: the History of Spaceflight Quarterly

Celebrating the Silver Anniversary of Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly 1992 - 2017 www.spacehistory101.com Celebrating the Silver Anniversary of Quest: The History of Spaceflight Quarterly Since 1992, 4XHVW7KH+LVWRU\RI6SDFHIOLJKW has collected, documented, and captured the history of the space. An award-winning publication that is the oldest peer reviewed journal dedicated exclusively to this topic, 4XHVW fills a vital need²ZKLFKLVZK\VRPDQ\ SHRSOHKDYHYROXQWHHUHGRYHUWKH\HDUV Astronaut Michael Collins once described Quest, its amazing how you are able to provide such detailed content while making it very readable. Written by professional historians, enthusiasts, stu- dents, and people who’ve worked in the field 4XHVW features the people, programs, politics that made the journey into space possible²human spaceflight, robotic exploration, military programs, international activities, and commercial ventures. What follows is a history of 4XHVW, written by the editors and publishers who over the past 25 years have worked with professional historians, enthusiasts, students, and people who worked in the field to capture a wealth of stories and information related to human spaceflight, robotic exploration, military programs, international activities, and commercial ventures. Glen Swanson Founder, Editor, Volume 1-6 Stephen Johnson Editor, Volume 7-12 David Arnold Editor, Volume 13-22 Christopher Gainor Editor, Volume 23-25+ Scott Sacknoff Publisher, Volume 7-25 (c) 2019 The Space 3.0 Foundation The Silver Anniversary of Quest 1 www.spacehistory101.com F EATURE: THE S ILVER A NNIVERSARY OF Q UEST From Countdown to Liftoff —The History of Quest Part I—Beginnings through the University of North Dakota Acquisition 1988-1998 By Glen E. -

View Pdf for Soviet Space Culture

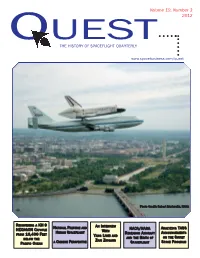

Volume 19, Number 3 2012 OUEST THE HISTORY OF SPACEFLIGHT QUARTERLY www.spacebusiness.com/quest Photo Credit: Robert Markowitz, NASA RECOVERING A KH-99 AN INTERVIEW NATIONAL PRESTIGE AND NACA/NASA ANALYZING TASS HEXAGON CAPSULE WITH HUMAN SPACEFLIGHT RESEARCH AIRCRAFT ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM 16,400 FEET YANG LIWEI AND AND THE BIRTH OF ON THE SOVIET BELOW THE HAI HIGANG A CHINESE PERSPECTIVE Z Z SPACE PROGRAM PACIFIC OCEAN SPACEFLIGHT Contents Volume 19 • Number 3 2012 www.spacebusiness.com/quest 4 An Underwater Ice Station Zebra More Reviews Recovering a KH-99 HEXAGON Capsule from 16,400 Feet Below the Pacific Ocean 64 Into the Blue: American Writing on Aviation and Spaceflight By David W. Waltrop Edited by Joseph J. Corn 18 National Prestige and Human Spaceflight Review by Dominick A. Pisano A Chinese Perspective 65 Destination Mars: By Liang Yang New Explorations of the Red Planet Book by Rod Pyle 31 China’s Great Leap into Space Review by Bob Craddock An Interview with Yang Liwei and Zhai Zhigang By John Vause 66 Soviet Space Culture Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies 36 NACA/NASA Research Aircraft and the Edited by Maurer, Richers, Rüthers, and Scheide Review by Michael J. Neufeld Birth of Spaceflight By Curtis Peebles 67 The Space Shuttle: Celebrating Thirty Years of NASA’s First Space Plane Managing the News: 44 Book by Piers Bizony Analyzing TASS Announcements on the Review by Roger D. Launius Soviet Space Program (1957-11964) By Bart Hendrickx 68 The Astronaut: Cultural Mythology and Idealised Masculinity Book Reviews Book by Dario Llinares Review by Amy E. -

Aeronautical, Spacecraft, and Launch Vehicle Examples

The Value of Identifying and Recovering Lost GN&C Lessons Learned: Aeronautical, Spacecraft, and Launch Vehicle Examples Cornelius J. Qennehy 1 NASA Engineering and Safety Center (NESC) Steve Labbe2 NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX, 77058 · Kenneth L. Lebsock3 Orbital Sciences Corporation, Technical Services Division, Greenbelt, MD 20770 Within the broad aerospace community the importance of identifying, documenting and widely sharing lessons learned during system development, flight test, operational or research programs/projects is broadly acknowledged. Documenting and sharing lessons learned helps managers and engineers to minimize project risk and improve performance of their systems. Often significant lessons learned on a project fail to get captured even though they are well known 'tribal knowledge" amongst the project team members. The physical act of actually writing down and documenting these lessons learned for the next generation of NASA GN&C engineers fails to happen on some projects for various reasons. In this paper we will first review the importance of capturing lessons learned and then wlll discuss reasons why some lessons are not documented. A simple proven approach called 'Pause and Learn' will be highlighted as a proven low-impact method of organizational learning that could foster the timely capture of critical lessons learned. Lastly some examples of "lost"GN&C lessons learned from the aeronautics, spacecraft and launch vehicle domains are briefly highlighted. In the context of this paper "lost" refers to lessons that have not achieved broad visibility within the NASA-wide GN&C CoP because they are either undocumented, masked or poorly documented in the NASA Lessons Learned Information System (LLIS). -

In This Issue

Vol. 38 No.12, September 2013 Editor: Jos Heyman FBIS In this issue: Satellite Update 4 Cancelled projects: Conestoga 5 News Ardusat 3 Arirang-5 7 Dnepr 1 7 Dream Chaser 7 Eutelsat and Satmex 2 Fermi 7 Gsat-14 7 HTV-4 3 iBall 3 Kepler 4 Orion 7 PicoDragon 3 Proton M 2 RCM 2 Russian EVAs 2 SARah 4 SGDC-1 4 SPRINT A 4 TechEdSat-3 3 WGS-6 4 HTV-4 Unpressurised Logistics Carrier with STP-H4 TIROS SPACE INFORMATION Eutelsat and Satmex 86 Barnevelder Bend, Southern River WA 6110, Australia Tel + 61 8 9398 1322 Eutelsat has acquired Mexico’s Satmex, a major communicaions satellite operator in the Latin (e-mail: [email protected]) American region. o o The Tiros Space Information (TSI) - News Bulletin is published to promote the scientific exploration and Satmex has currently three satellites in orbit at 113 W (Satmex-6), 114.9 W (Satmex-5) and commercial application of space through the dissemination of current news and historical facts. 116.8 oW (Satmex-8) and it can be expected that, once the acquisition has been completed, In doing so, Tiros Space Information continues the traditions of the Western Australian Branch of the these satellites will be renamed as part of the Eutelsat family. In addition Satmex has the Astronautical Society of Australia (1973-1975) and the Astronautical Society of Western Australia (ASWA) Satmex-7 and -9 satellites on order from Boeing. It is not clear whether these satellites will (1975-2006). remain on order. The News Bulletin can be received worldwide by e-mail subscription only. -

A History of Appalachia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 2-28-2001 A History of Appalachia Richard B. Drake Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Drake, Richard B., "A History of Appalachia" (2001). Appalachian Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/23 R IC H ARD B . D RA K E A History of Appalachia A of History Appalachia RICHARD B. DRAKE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the E.O. Robinson Mountain Fund and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2003 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kenhlcky Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drake, Richard B., 1925- A history of Appalachia / Richard B. -

Rockets for Education 5 June 2019

Rockets for education 5 June 2019 Technology, Poland. Several modular experiments are held in the circular containers imaged here. Called Hedgehog, the experiment tested patented instruments for measuring acceleration, vibration and heat flow during launch. The team hopes to refine the tools for use on ground-based qualification tests that all payloads must pass before launch. At launch, Rexus produces a peak vertical acceleration of around 17 times the force of gravity. Once the rocket motors shut off, the experiments enter freefall. On the downward arc parachutes deploy, lowering the experiments to the ground for transport back to the launch site by helicopter as quickly as possible. Credit: European Space Agency A service module sends data and receives commands from the ground to keep everything on course while sending videos and data to ground Why rockets are so captivating is not exactly rocket stations. science. Watching a chunk of metal defy the forces of gravity satisfies many a human's wish to soar ESA has used sounding rockets for over 30 years through the air and into space. to investigate phenomena under microgravity from the state-of-the-art facilities are available at Today there are countless rockets to satisfy the Esrange. The laboratories include microscopes, itch, and they are not all big launchers delivering centrifuges and incubators so investigators can heavy satellites into space, like Europe's Ariane 5 prepare and analyse their experiments around and the upcoming Ariane 6. flight. Sounding rockets, like this Rexus (Rocket Coordinated by ESA Education, the Rexus/Bexus Experiments for University Students) being programme launches two sounding rockets a year assembled at the ZARM facilities in Bremen, and provides an experimental near-space platform Germany, are launched regularly in the name of for students who can work on different research science from the Esrange Space Center in areas from atmospheric research and fluid physics, northern Sweden. -

A Review of Alterations to the Brain During Spaceflight and the Potential

www.nature.com/npjmgrav REVIEW ARTICLE OPEN A review of alterations to the brain during spaceflight and the potential relevance to crew in long-duration space exploration ✉ Meaghan Roy-O’Reilly 1,2 , Ajitkumar Mulavara3 and Thomas Williams4 During spaceflight, the central nervous system (CNS) is exposed to a complex array of environmental stressors. However, the effects of long-duration spaceflight on the CNS and the resulting impact to crew health and operational performance remain largely unknown. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge regarding spaceflight-associated changes to the brain as measured by magnetic resonance imaging, particularly as they relate to mission duration. Numerous studies have reported macrostructural changes to the brain after spaceflight, including alterations in brain position, tissue volumes and cerebrospinal fluid distribution and dynamics. Changes in brain tissue microstructure and connectivity were also described, involving regions related to vestibular, cerebellar, visual, motor, somatosensory and cognitive function. Several alterations were also associated with exposure to analogs of spaceflight, providing evidence that brain changes likely result from cumulative exposure to multiple independent environmental stressors. Whereas several studies noted that changes to the brain become more pronounced with increasing mission duration, it remains unclear if these changes represent compensatory phenomena or maladaptive dysregulations. Future work is needed to understand how spaceflight-associated changes to the brain affect crew health and performance, with the goal of developing comprehensive monitoring and countermeasure strategies for future long-duration space exploration. npj Microgravity (2021) 7:5 ; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-021-00133-z 1234567890():,; BACKGROUND with increased mission length4,8,9.