Thesis Become a Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multi-Platform Programming for Digital TV

Multi-Platform Programming for Digital TV German-Japanese Symposium 2007 Session 7: New convergence based applications Berlin, April 20, 2007 Thomas Schultheis, Managing Director, SevenSenses GmbH Agenda German TV market overview Company and business overview Diversification - PayTV - Video on Demand - Mobile 2 Market overview German TV market: On average 54 TV stations per household Private FTA Private FTA Private FTA Public Stations Special Interest Pay TV 38.5%* 18.5%* 26.8%* 13.8%* 2.4%* (1st tier channels) (2nd tier channels) (3rd tier channels) ARD Sat.1 kabel eins ZDF ProSieben RTL II Arte 3Sat RTL VOX ARD Dritte (7 regional channels) Kinderkanal Phoenix et al. et al. Total TV households: 35 million Cable: ~20 million (54%), satellite: ~16.4 million (42%), terrestrial: ~2.1 million (5%) Conclusion: The German TV market, with an average of 54 TV stations per household**, is already fragmented * Audience market share Mon.-Sun., 03:00-03:00 h, viewers 14-49, average 2006; Private FTA Special Interest is the difference to the total of 100 ** Free-to-air and Pay TV channels; as at January 1, 2007 3 Basis: All TV households (Germany + EU), Source: AGF/GfK-Fernsehforschung, pc#tv aktuell, SevenOne Media Marketing & Research Agenda German TV market overview Company and business overview Diversification - PayTV - Video on Demand - Mobile 4 Company overview The ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG is the leading electronic media group in Germany. We provide people with first -class entertainment and comprehensive information – whenever they need it, wherever they are. Company overview ProSiebenSat.1Media AG – Company Trailer 6 Company overview The ProSiebenSat.1 Group ProSiebenSat.1 is the only Group that operates four wholly owned advertising financed TV stations in Germany and their related ancillary and diversification activities. -

Distributionplans 2011

D I S T R I B U T I O N P L A N S 2011 as amended by the Board on 20/11/2012, 04/12/2012, 27/06/2013, 18/11/2013, 04/03/2014, 17/11/2014, 18/03/2015, 19/04/2016, 15/11/2016, and as resolved by the Assembly of Shareholders and Delegates1 on 21/06/2017, 07/12/2017, 20/11/2018, 16/06/2020, 19/08/2020 and 13/11/2020 I. GENERAL 1. As long as individual shares can be established with adequate means, each rights holder shall receive their share relating to the usage of his contribution to a performance from the amount collected after deduction of the effective costs and any allocations for cultural and social purposes. 2. In cases where the individual usage share of the collected amount cannot be established with adequate means, general evaluation and distribution rules for a general approach to this method of measuring the relevant share shall be established. The scope of the usage, the cultural or artistic significance of each rights holder’s performance shall be considered adequately. Minimum thresholds for collecting usage data and setting pay-out levels to rights holders shall be permissible. 3. Any rights holders’ remuneration entitlements, their exploitation rights or other rights assigned to GVL shall be governed by the distribution plans, even if the agreement between the rights holder and the user includes deviating provisions. 4. The distribution includes: a) remuneration collected for the 2011 financial year . for broadcasts of commercially published sound recordings2 and video clips, . -

Unitymedia Kabel Deutschland Kabel BW Netcologne Kabelkiosk 1-2-3.Tv

Unitymedia Kabel Deutschland Kabel BW Netcologne KabelKiosk 1-2-3.tv Digital TV BASIC Kabel Digital Free FtA FtA n/a Digital TV PLUS Kabel Digital Home Kabel Digital Home Familie th KabelKiosk Family XL 13 Street Premiere Familie Premiere Familie Premiere Familie Premiere Familie 3Sat FtA FtA FtA FtA n/a 4 Music n/a n/a FtA n/a n/a 9Live Digital TV BASIC Kabel Digital Free FtA FtA KabelKiosk Basis Adult Channel n/a n/a n/a Familie KabelKiosk Sports Al Auola Inter n/a n/a FtA n/a n/a Al Jazeera (arabisch) Digital TV BONUS n/a FtA FtA n/a Al Jazeera Children's (arabisch) n/a n/a FtA FtA n/a Al Jazeera International (englisch) Digital TV BASIC Kabel Digital Free FtA FtA n/a Al-Safwa n/a n/a n/a n/a Arabisch Al-Yawn n/a n/a n/a n/a Arabisch Alpenglühen TVX n/a n/a Männer Paket n/a n/a Alsat n/a n/a Albanien n/a n/a Animal Planet Premiere Familie Premiere Familie Premiere Familie Premiere Familie n/a Animax Digital TV PLUS Kabel Digital Home Kabel Digital Home n/a n/a Anixe HD n/a FtA FtA FtA n/a Anixe SD Digital TV BASIC Kabel Digital Free FtA FtA n/a ANN n/a Kabel Digital Free n/a n/a n/a Arirang TV n/a n/a FtA n/a n/a ART Hekayat (arabisch) Digital TV Arabisch n/a n/a n/a n/a ART Movie 1 (arabisch) Digital TV Arabisch n/a n/a n/a n/a ART Prime Sport (arabisch) Digital TV Arabisch n/a n/a n/a n/a arte FtA FtA FtA FtA n/a Astra HD+ n/a n/a n/a FtA n/a Astro TV Digital TV BASIC Kabel Digital Free FtA FtA n/a Digital TV Türkei Kabel Digital Türkisch Türkisch Türkisch Unterhaltung Türkisch Basis ATV Avrupa Digital TV Türkei Premium Kabel Digital -

Anmeldung Von Beteiligungsveränderungen Bei Tochtergesellschaften Der Prosiebensat.1 Media AG

Anmeldung von Beteiligungsveränderungen bei Tochtergesellschaften der ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG Aktenzeichen: KEK 669 (-1 bis -6) Beschluss In der Rundfunkangelegenheit der 1. Sat.1 SatellitenFernsehen GmbH, vertreten durch die Geschäftsführer Andreas Bartl und Joachim Kosack, Medienallee 7, 85774 Unterföhring, 2. ProSieben Television GmbH, vertreten durch den Geschäftsführer Jürgen Hörner, Me- dienallee 7, 85774 Unterföhring, 3. kabel eins Fernsehen GmbH, vertreten durch den Geschäftsführer Karl König, Medien- allee 7, 85774 Unterföhring, 4. 9Live Fernsehen GmbH, vertreten durch den Geschäftsführer Ralf Bartoleit, Guten- bergstraße 1, 85774 Unterföhring, 5. SevenSenses GmbH, vertreten durch den Geschäftsführer Christoph Bellmer, Medien- allee 7, 85774 Unterföhring, und der 6. ProSiebenSat.1 Erste Verwaltungsgesellschaft mbH, vertreten durch die Geschäftsfüh- rer Katja Hofem-Best und Andreas Bartl, Medienallee 7, 85774 Unterföhring - Veranstalter - Bevollmächtigte: XXX …, w e g e n mittelbarer Veränderungen von Beteiligungsverhältnissen 2 hat die Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich (KEK) auf die Vorla- ge der Landeszentrale für Medien und Kommunikation Rheinland-Pfalz (LMK) vom 15.06.2011, die auch im Namen der Bayerischen Landeszentrale für neue Medien (BLM), und der Medienanstalt Berlin-Brandenburg (mabb) erfolgte, in der Sitzung am 09.08.2011 unter Mitwirkung ihrer Mitglieder Dr. Lübbert (Vorsitzender), Prof. Dr. Dörr, Prof. Dr. Gou- nalakis, Dr. Grüning, Dr. Hege, Dr. Hornauer, Prof. Dr. Mailänder, Dr. Schwarz, -

Download (954Kb)

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 28.7.2004 SEC(2004) 1016 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING PAPER Annex to the Sixth Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on the application of Articles 4 and 5 of Directive 89/552/EEC "Television without Frontiers", as amended by Directive 97/36/EC, for the period 2001-2002 {COM(2004)524 final} EN EN TABLE OF ANNEXES ANNEX 1 - Performance indicators ........................................................................................ 4 ANNEX 2 - Tables on the application of Articles 4 and 5 ...................................................... 6 ANNEX 3 - Application of Articles 4 and 5 in each Member State........................................ 8 ANNEX 4 - Summary of the reports from the Member States.............................................. 39 ANNEX 5 - Summary of the reports from the Member States of the European Free Trade Association participating in the European Economic Area ................... 114 ANNEX 6 - List of television channels in the European Union Member States which failed to achieve the majority proportion according to Article 4 ..................... 118 ANNEX 7 – Average transmission time of European works according to Article 4 taking audience shares of channels into account (“de-minimis-criterion”) .... 128 ANNEX 8 – List of television channels in the European Union Member States which failed to achieve the minimum proportion according to article 5 ................... 132 EN 2 EN This document complements the Sixth Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on the application of Articles 4 and 5 of Directive 89/552/EEC 1 of 3 October 1989, as amended by Directive 97/36/EC 2 - hereinafter referred to as the “Television without frontiers” Directive - for the period 2001-2002. -

Silverline Movie Channel“

Zulassungsantrag der Silverline Television AG für das Fernsehspartenprogramm „Silverline Movie Channel“ Aktenzeichen: KEK 677-1 Beschluss In der Rundfunkangelegenheit der Silverline Television AG, vertreten durch ihren Vorstand Axel Münch, Münchner Straße 42, 82008 Unterhaching, – Antragstellerin – w e g e n Verlängerung der Zulassung zur bundesweiten Veranstaltung des Fernsehspartenpro- gramms „Silverline Movie Channel“ hat die Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich (KEK) auf Vorlage der Sächsischen Landesanstalt für privaten Rundfunk und neue Medien (SLM) vom 26.09.2011 in der Sitzung am 13.12.2011 unter Mitwirkung ihrer Mitglieder Dr. Lübbert (stv. Vorsitzender), Dr. Bauer, Dr. Brautmeier, Prof. Dr. Dörr, Fuchs, Prof. Dr. Gounalakis, Dr. Hege, Dr. Hornauer, Prof. Dr. Mailänder, Prof. Dr. Müller-Terpitz, Prof. Dr. Schwarz und Prof. Thaenert entschieden: Der von der Silverline Television AG mit Schreiben vom 05.09.2011 bei der Säch- sischen Landesanstalt für privaten Rundfunk und neue Medien (SLM) beantrag- ten Verlängerung der Zulassung für das bundesweit verbreitete Fernsehsparten- programm Silverline Movie Channel stehen Gründe der Sicherung der Mei- nungsvielfalt im Fernsehen nicht entgegen. 2 Begründung I Sachverhalt 1 Zulassungsantrag Die Silverline Television AG („Silverline Television“) hat mit Schreiben vom 05.09.2011 bei der SLM die Verlängerung ihrer Lizenz für das bundesweite Fernseh- spartenprogramm Silverline Movie Channel für einen Zeitraum von zehn Jahren be- antragt (Az.: KEK 677-1). Die derzeit geltende Lizenz endet zum 31.12.2011. Mit Schreiben vom 26.09.2011 hat die SLM der KEK die Anträge zur medienkonzentra- tionsrechtlichen Prüfung vorgelegt. Mit Schreiben vom 05.09.2011 hat Silverline Television zugleich die Zulassung für das weitere bundesweite Fernsehspartenprogramm Silverline HD beantragt (Az.: KEK 677-2). -

Aucun Titre De Diapositive

Channels available programme by programme, territory by territory, via Eurodata TV Worldwide. * Channels measured only on a minute by minute basis are available on an ad-hoc basis “Standard countries” : data available in house, catalogue tariffs are applied “Non-standard countries” : Ad hoc tariffs are applied “Special countries” : special rate card applies “Standard countries” : Eurodata TV’s tariffs are applied, “Non-standard10/05/2006 countries” : Ad hoc tariffs are applied “Special countries” : Fixed and separated prices apply data available in Paris except for channels in blue 14/02/2006 issue This document is subject to change Channels available programme by programme in EUROPE AUSTRIA BELGIUM BOSNIA HERZEGOVINA BULGARIA CROATIA ORF1 ZDF NORTH SOUTH BHT 1 TV TK ALEXANDRA TV GTV HTV 1 ORF2 ATV+ EEN (ex TV1) LA 1 FTV TV TUZLA BBT FoxLife HTV 2 3SAT KANAAL 2 LA 2 HTV OSCAR C BTV NOVA TV ARD Channels available on KETNET/CANVAS RTL - TVI NTV HAYAT BNT/Channel 1 RTL KABEL 1 ad-hoc NICKELODEON CLUB RTL OBN DIEMA 2 PRO7 ARTE SPORZA AB 3 Pink BiH DIEMA + RTL DSF VIJFTV AB 4 RTRS NOVA TV RTL II EUROSPORT VITAYA PLUG TV RTV MOSTAR MM SAT 1 GOTV VT4 BE 1 (ex CANAL+) RTV TRAVNIK MSAT SUPER RTL Puls TV VTM TV BN Evropa TV VOX TW1 Planeta TV TELETEST / FESSEL - GFK/ORF CIM - AUDIMETRIE MARECO INDEX BOSNIA TNS TV PLAN AGB NMR CYPRUS CZECH REP DENMARK ESTONIA FINLAND FRANCE GERMANY ANT 1 CT 1 3+ EESTI TV (ETV) YLE 1 TF1 ARD ARTE SUPER RTL O LOGOS CT 2 ANIMAL PLANET KANAL 2 YLE 2 FRANCE 2 ZDF 3SAT NTV RIK 1 TV NOVA DISCOVERY PBK MTV FRANCE 3 HESSEN -

Zulassungsantrag Der Sat.1 Satellitenfernsehen Gmbh Für Das Fernsehvollprogramm Sat.1

Zulassungsantrag der Sat.1 SatellitenFernsehen GmbH für das Fernsehvollprogramm Sat.1 Aktenzeichen: KEK 505 Beschluss In der Rundfunkangelegenheit der Sat.1 SatellitenFernsehen GmbH, vertreten durch die Geschäftsführer Matthias Al- berti und Dr. Torsten Rossmann, Oberwallstraße 6, 10117 Berlin, - Antragstellerin - w e g e n Verlängerung der Zulassung zur Veranstaltung des bundesweiten Fernsehvollpro- gramms Sat.1 hat die Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich (KEK) auf Vorlage der Landeszentrale für Medien und Kommunikation Rheinland-Pfalz (LMK) vom 17.06.2008 in der Sitzung am 19.08.2008 unter Mitwirkung ihrer Mitglieder Prof. Dr. Sjurts (Vorsitzende), Prof. Dr. Huber, Dr. Lübbert und Prof. Dr. Mailänder entschieden: Der von der Sat.1 SatellitenFernsehen GmbH mit Schreiben vom 12.06.2008 bei der Landeszentrale für Medien und Kommunikation Rheinland-Pfalz (LMK) bean- tragten Verlängerung der Zulassung zur Veranstaltung des bundesweit verbrei- teten Fernsehvollprogramms Sat.1 stehen Gründe der Sicherung der Meinungs- vielfalt im Fernsehen nicht entgegen. 2 Begründung I Sachverhalt 1 Zulassungsantrag Die Sat.1 SatellitenFernsehen GmbH („Sat.1 GmbH“) hat mit Schreiben vom 12.06.2008 bei der BLM die Verlängerung ihrer Zulassung für das bundesweite Fernsehvollprogramm Sat.1 um weitere zehn Jahre beantragt. Die Laufzeit der der- zeit gültigen Zulassung der LMK endet mit Ablauf des 31.05.2010. Die LMK hat der KEK den Antrag mit Schreiben vom 17.06.2008 zur medienkonzentrationsrechtli- chen Prüfung vorgelegt. 2 Programmstruktur und -verbreitung Bei Sat.1 handelt es sich um ein Fernsehvollprogramm, dessen „Programmsäulen“ deutsche Fiktion (Serien, TV-Movies, Kinoproduktionen und Event-Mehrteiler), En- tertainment (Shows und Comedies), Infotainment (Magazine, Reportagen, Doku- soaps und -serien), aktuelle Information (Nachrichten und Regionalprogramme), Li- zenz-Serien und -Spielfilme sowie Sport bilden. -

Unitydigital TV-Programmangebot

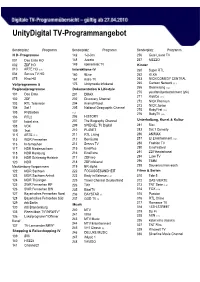

UnityDigital TV-Programmangebot Senderplatz Programm Senderplatz Programm Senderplatz Programm H D- Programme 142 1-2-3.tv 256 Gute Laune TV 001 Das Erste HO 148 Juwelo 257 MEZZO 002 ZDF HO 149 sonnenklar.TV Kinder 010 ARTE HO (1,3) Interaktions-lV 260 Super RTL 034 Servus TV HO 160 9Live 262 KI.KA 075 Kino HO 263 NICK/COMEDY CENTRAL 167 Astro TV Vollprogramme & 175 Unitymedia Infokanal 265 Cartoon Network (1, 2) 266 Boomerang (1,2) Regionalprogramme Dokumentation & Lifestyle 270 yourfamilyentertainment (yfe) 101 Das Erste 201 DMAX 271 KidsCo (1,2) 102 ZDF 202 Discovery Channel 272 NICK Premium 103 RTL Television 204 Animal Planet 273 NICK Junior 104 Sat.1 205 National Geographic Channel 275 BabyFirst (1,2) 105 ProSieben (1,2) 276 BabyTV (1,2) 106 RTL2 206 HISTORY Unterhaltung, Kunst & Kultur 107 kabel eins 207 The Biography Channel 108 VOX 209 SPIEGEL TV Digital 281 Sixx 109 3sat 210 PLANET 283 Sat.1 Comedy 11 0 ARTE (1, 3) 211 RTL Living 286 ANIMAX 115 WDR Fernsehen 212 BonGusto 287 E! Entertainment (1,2) 116 hr-fernsehen 214 Servus TV 288 Fashion TV 117 NDR Niedersachsen 215 EinsPlus 290 EinsFestival 118 NDR Hamburg 216 EinsExtra 291 ZDFtheaterkanal 119 NDR Schieswig-Hoistein 217 ZDFneo 294 Luxe TV 120 NDR 218 ZDFinfokanal 296 TIMM Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 219 BR-alpha 298 Souvenirs from earth 122 MDR Sachsen 222 FOCUSGESUNDHEIT Filme & Serien 123 MDR Sachsen-Anhalt 223 Body in Balance (1,2) 310 Tele 5 124 MDR Thüringen 225 Travel Channel Deutschland 312 DAS VIERTE 125 SWR Fernsehen RP 226 TW1 313 TNT Serie (1,2) 126 SWR Fernsehen BW -

Prosiebensat.1 Media SE Annual Report 2019 KEY FIGURES of PROSIEBENSAT.1 GROUP in EUR M

DIGITAL ATTACK · CONSUMER FOCUSED · TOTAL REACH & MONETIZATION ProSiebenSat.1 Media SE Annual Report 2019 KEY FIGURES OF PROSIEBENSAT.1 GROUP in EUR m 2019 2018 Revenues 4,135 4,009 Revenue margin before income taxes (in %) 13.8 8.6 Total costs 3,592 3,710 Operating costs 1 3,297 3,027 Consumption of programming assets 958 1,319 Adjusted EBITDA 2 872 1,013 Adjusted EBITDA margin (in %) 21.1 25.3 EBITDA 838 570 Reconciling items 3 – 34 – 443 Operating result (EBIT) 578 348 Adjusted EBIT 684 850 Financial result – 6 – 4 Result before income taxes 572 344 Adjusted net income 4 387 541 Net income 412 250 Net income attributable to shareholders of ProSiebenSat.1 Media SE 413 248 Net income attributable to non-controlling interests – 1 1 Adjusted earnings per share (in EUR) 1.71 2.36 Payments for the acquisition of programming assets 1,072 1,070 Free cash flow 207 – 78 Cash flow from financing activities – 294 – 468 Free cash flow before M&A 339 244 12/31/2019 12/31/2018 Employees 5 7, 253 6,583 Programming assets 1,204 1,113 Equity 1,288 1,070 Equity ratio (in %) 19.5 16.5 Cash and cash equivalents 950 1,031 Financial debt 3,195 3,194 Leverage ratio 6 2.6 2.1 Net financial debt 2,245 2,163 1 Total costs excl. expense adjustments, depreciation, amortization, and impairments. 2 EBITDA before reconciling items. 3 Expense adjustments less income adjustments. 4 Net income attributable to shareholders of ProSiebenSat.1 Media SE before the amortization and impairments from purchase price allocations, adjusted for the reconciling items. -

Fernseh- U. Rundfunk-Programmübersicht Übertragungsrechtlichen Gründen Vorbehalten

Stand: 01.05.2012 Änderungen aus technischen oder Fernseh- u. Rundfunk-Programmübersicht übertragungsrechtlichen Gründen vorbehalten Analoge TV Sender Analoge Radio Sender Sendername Kanal Ihre Sendername Frequenz Progr.-Nr. kabel eins S 06 Österreich 1 87,60 VOX S 07 SWR 1 Baden-Württemberg 87,90 SWR 2 Baden-Württemberg 88,40 N24 S 08 BR 2 Schwaben 89,05 ORF 1 S 09 Österreich 2 Radio Vorarlberg 89,85 ORF 2 S 10 Österreich 3 90,15 ARD (Das Erste) K 05 FM 4 90,80 ZDF K 06 ERF Radio 91,30 SWR Fernsehen (BW) K 07 Radio Horeb 92,15 Bayerisches Fernsehen K 08 SWR 4 Schwabenradio 93,15 RTL K 09 RTL Radio 94,60 SAT.1 K 10 BR 1 Schwaben 95,25 arte K 11 Deutschlandfunk 96,70 Radio 7 Ulm 97,55 Sport 1 K 12 JAM FM 98,80 Super RTL S 11 Donau 3 FM 99,25 KI.KA S 12 BR 3 99,55 3sat S 13 SWR 4 Bodenseeradio 100,15 Pro Sieben S 14 DAS DING 101,20 Eurosport S 15 SWR 3 101,65 RTL 2 S 16 Bayern 4 Klassik 102,25 Regio TV (Ulm) S 17 Radio Melodie 103,35 Phoenix S 18 Deutschlandradio 103,65 Radio 7 Oberschwaben 104,10 RTR 1 (russ.) S 19 Klassik Radio 104,70 B5 aktuell 105,45 ANTENNE BAYERN 105,75 Schweizer Radio DRS 3 107,15 sunshine live 107,50 Stand: 14.02.2011 Änderungen aus technischen oder Fernseh- u. Rundfunk-Programmübersicht Übertragungsrechtlichen Gründen vorbehalten Digital TV + HDTV Sender (kostenfrei) Kanal Kanal Kanal Sendername Sendername Sendername Frequenz Frequenz Frequenz Modulation Modulation Modulation Symbolrate Symbolrate Symbolrate Sat 1 ARD (Das Erste) ZDF S 02 ProSieben Bayerisches Fernsehen Süd S 21 ZDFinfokanal S 24 114,0 MHz Kabel -

Pressemitteilung 1/2011 14469 Potsdam

K E K Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich Geschäftsstelle Helene-Lange-Straße 18 a Pressemitteilung 1/2011 14469 Potsdam Tel.: (03 31) 2 00 63 60 Fax: (03 31) 2 00 63 70 E-Mail: [email protected] http://www.kek-online.de 165. Sitzung der KEK am 11.01.2011 Zulassungsantrag 9Live / 9Live Fernsehen GmbH Zulassungsantrag Mobility Channel / MC TV GmbH Beteiligungsveränderung / ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG Beteiligungsveränderung / Da Vinci Media GmbH Die Kommission zur Ermittlung der Konzentration im Medienbereich (KEK) hat ent- schieden, dass den folgenden Zulassungen und Beteiligungsveränderungen keine Gründe der Sicherung der Meinungsvielfalt entgegenstehen: Zulassungsantrag 9Live / 9Live Fernsehen GmbH Die 9Live Fernsehen GmbH hat bei der Bayerischen Landeszentrale für neue Medien (BLM) die Ver- längerung der Zulassung für das Fernsehspartenprogramm 9Live beantragt. Das Programm wird der- zeit aufgrund einer bis zum 30.04.2011 befristeten Zulassung veranstaltet. 9Live ist ein Unterhal- tungsspartenprogramm, das schwerpunktmäßig auf interaktive Angebotsformen wie Gewinnspiele, Quizshows und Teleshopping ausgerichtet ist. 9Live wird frei empfangbar analog und digital über Ka- bel, Satellit (Astra) sowie digital terrestrisch (DVB-T) verbreitet. Des Weiteren wird das Programm über IPTV-Plattformen ausgestrahlt. Alleingesellschafterin der 9Live Fernsehen GmbH ist die ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG. Weitere Tochter- gesellschaften der ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG veranstalten die Programme Sat.1, ProSieben, kabel eins, 9Live, SIXX, Sat.1 Comedy und kabel eins classics und halten Lizenzen für die noch nicht auf Sendung befindlichen Programme Movie Channel, ProSiebenSat.1 Family, ProSiebenSat.1 Fiction, ProSiebenSat.1 Fun, ProSiebenSat.1 Favorites und ProSiebenSat.1 Facts. 88 % der Stammaktien der ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG hält über eine Kette von 100 %igen Tochterge- sellschaften die Lavena 1 S.A.R.L.