Self-Help, Social Housing and Rehab in Santiago, Chile Peter M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

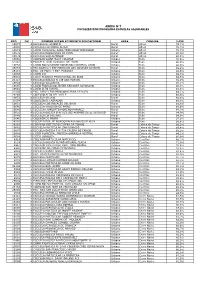

Rbd Dv Nombre Establecimiento

ANEXO N°7 FOCALIZACIÓN PROGRAMA ESCUELAS SALUDABLES RBD DV NOMBRE ESTABLECIMIENTO EDUCACIONAL AREA COMUNA %IVE 10877 4 ESCUELA EL ASIENTO Rural Alhué 74,7% 10880 4 ESCUELA HACIENDA ALHUE Rural Alhué 78,3% 10873 1 LICEO MUNICIPAL SARA TRONCOSO TRONCOSO Urbano Alhué 78,7% 10878 2 ESCUELA BARRANCAS DE PICHI Rural Alhué 80,0% 10879 0 ESCUELA SAN ALFONSO Rural Alhué 90,3% 10662 3 COLEGIO SAINT MARY COLLEGE Urbano Buin 76,5% 31081 6 ESCUELA SAN IGNACIO DE BUIN Urbano Buin 86,0% 10658 5 LICEO POLIVALENTE MODERNO CARDENAL CARO Urbano Buin 86,0% 26015 0 ESC.BASICA Y ESP.MARIA DE LOS ANGELES DE BUIN Rural Buin 88,2% 26111 4 ESC. DE PARV. Y ESP. PUKARAY Urbano Buin 88,6% 10638 0 LICEO 131 Urbano Buin 89,3% 25591 2 LICEO TECNICO PROFESIONAL DE BUIN Urbano Buin 89,5% 26117 3 ESCUELA BÁSICA N 149 SAN MARCEL Urbano Buin 89,9% 10643 7 ESCUELA VILLASECA Urbano Buin 90,1% 10645 3 LICEO FRANCISCO JAVIER KRUGGER ALVARADO Urbano Buin 90,8% 10641 0 LICEO ALTO JAHUEL Urbano Buin 91,8% 31036 0 ESC. PARV.Y ESP MUNDOPALABRA DE BUIN Urbano Buin 92,1% 26269 2 COLEGIO ALTO DEL VALLE Urbano Buin 92,5% 10652 6 ESCUELA VILUCO Rural Buin 92,6% 31054 9 COLEGIO EL LABRADOR Urbano Buin 93,6% 10651 8 ESCUELA LOS ROSALES DEL BAJO Rural Buin 93,8% 10646 1 ESCUELA VALDIVIA DE PAINE Urbano Buin 93,9% 10649 6 ESCUELA HUMBERTO MORENO RAMIREZ Rural Buin 94,3% 10656 9 ESCUELA BASICA G-N°813 LOS AROMOS DE EL RECURSO Rural Buin 94,9% 10648 8 ESCUELA LO SALINAS Rural Buin 94,9% 10640 2 COLEGIO DE MAIPO Urbano Buin 97,9% 26202 1 ESCUELA ESP. -

Interculturalidad En Municipalidades De La Región Metropolitana

INTERCULTURALIDAD EN MUNICIPALIDADES DE LA REGIÓN METROPOLITANA Desafíos y buenas prácticas de los gobiernos locales en torno al trabajo con población migrante Deydi Ortega Colocho (autora) Carolina Ormazábal Méndez Paula Olivares González (colaboradoras) Diciembre, 2019 Tabla de contenido Resumen ejecutivo 3 1. Introducción 4 2. Marco teórico 5 2.1. La Migración y las políticas públicas 5 2.2. Enfoques ante la diversidad cultural 6 2.2.1. Enfoque intercultural e interculturalidad 7 2.3. Municipios Interculturales 8 2.3.1. Un municipio inclusivo 8 2.3.2. Un municipio que considera los saberes de sus habitantes 9 2.3.3. El municipio que promueve el diálogo intercultural 9 2.3.4. Un municipio que es reflexivo visibiliza y transforma las prácticas abusivas y/o discriminatorias 10 3. Contexto de la migración en el mundo y en Chile 11 4. Diseño Metodológico 11 4.1. Estudio Exploratorio 12 4.2. Metodología 12 4.3. Análisis y lectura de este informe 13 4.4. Estándar ético 13 5. Buenas prácticas en torno a la interculturalidad 13 5.1. Prácticas de los municipios para la inclusión 14 5.1.1. Conocimiento de la composición de sus habitantes 14 5.1.2. Protección de los derechos de los ciudadanos y ciudadanas 15 5.1.3. Promoción de los derechos de ciudadanos y ciudadanas 18 5.1.4. Conocimiento de barreras para la inclusión 18 5.1.5. Definición de rutas de acción para la inclusión como ciudadanos y ciudadanas 19 5.1.6. Entrega no segregada de servicios 20 5.2. Prácticas de los municipios en las que se consideran los saberes 21 5.2.1. -

Movimientos Juveniles En Tres Ciudades De Chile

Evaluación de capacidades institucionales de las organizaciones y los movimientos juveniles en América del Sur MÁS DERECHOS JUVENILES... MÁS SEGURIDAD, MÁS INTEGRACIÓN, MÁS DEMOCRACIA. AGRUPACIONES, COLECTIVOS Y MOVIMIENTOS JUVENILES EN CUATRO CIUDADES DE CHILE (CONCEPCIÓN, VIÑA DEL MAR, CERRO NAVIA Y EL BOSQUE): ESTADO DE SITUACIÓN Y PROPUESTAS PARA SU FORTALECIMIENTO (*) Andrea Iglesis Larroquette (**) (*)Informe redactado en el marco del Estudio “Evaluación de las Capacidades Institucionales de los Movimientos Juveniles en el Mercosur”, implementado por el Centro Latinoamericano sobre Juventud (CELAJU), con el apoyo del Banco Mundial y la UNESCO. (**)Psicóloga Chilena. Coordinadora Diploma “Juventud y Co - Construcción de Políticas Locales”. Universidad de Concepción - ACHNU. Coordinadora Ejecutiva Mesa Regional de ONGs de Infancia y Juventud de Chile. ÍNDICE Introducción 05 I MARCO DE REFERENCIA 07 1.-Descripción del Contexto Nacional 07 2.-Descripción del Contexto de las Ciudades Incluidas 12 2.1 La Comuna de Concepción 12 2.2 La Comuna de Viña del Mar 13 2.3 La Comuna de Cerro Navia 13 2.4 La Comuna del Bosque 13 3.-Descripción de la Situación de las y los jóvenes 14 3.1 Jóvenes de Concepción 14 3.2 Jóvenes de Viña del Mar 15 3.3 Jóvenes de Cerro Navía 15 3.4 Jóvenes de El Bosque 16 II ORGANIZaciones Y Movimientos Juveniles 17 4.- Estado de Conocimiento sobre el tema 17 5.-Descripcion General y Particular de los movimientos existentes 23 6.-¿Movimiento Social, Actor Estratégicos o Sector Poblacional? 27 III Participación JUVENIL -

Actualización Plan Regulador Comunal De Cerro Navia Memoria Explicativa

PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL DE CERRO NAVIA: MEMORIA EXPLICATIVA I. MUNICIPALIDAD DE CERRO NAVIA ACTUALIZACIÓN PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL DE CERRO NAVIA MEMORIA EXPLICATIVA Mayo 2019 I. MUNICIPALIDAD DE CERRO NAVIA PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL DE CERRO NAVIA: MEMORIA EXPLICATIVA ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS 1 PRESENTACIÓN ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2 INTEGRANTES DEL EQUIPO ASESOR ................................................................................................. 3 A. PLANTEAMIENTO GENERAL ............................................................................................................... 5 1 INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2 CONTEXTO GENERAL ............................................................................................................................. 6 B. MARCO NORMATIVO ........................................................................................................................... 11 1 MARCO LEGISLATIVO .......................................................................................................................... 11 2 INSTRUMENTOS DE PLANIFICACIÓN TERRITORIAL ................................................................. 12 2.1 PLAN REGULADOR METROPOLITANO DE SANTIAGO (PRMS) ...................................................... 12 2.2 PLAN REGULADOR DE CERRO NAVIA -

Enel X, Metbus and BYD Open Latin America's First Exclusive Electric Bus

Media Relations PRESS T +56 2 26752746 RELEASE [email protected] ENEL X, METBUS AND BYD OPEN LATIN AMERICA’S FIRST FULLY ELECTRIC BUS ROUTE • The integration of 183 new electric buses makes Greater Santiago the first city in Latin America to implement a sustainable electric route, with a total of 285 zero- emission public transport units. • Additionally, with the goal of improving users’ travel experience, the new electric route includes innovative infrastructure items, with a number of cutting-edge bus stops that offer services such as LED lighting, information panels, and USB chargers. Santiago, October 15, 2019 – Enel X, Metbus, and BYD have opened Latin America’s first electric bus route, a comprehensive sustainable transport system that will feature 100% electric buses, making Chile the region’s leading country for electric transport. The event, attended by President Sebastián Piñera and Transport Minister Gloria Hutt, opened with an electric bus ride along the route, which links the districts of Ñuñoa and Peñalolén, stopping to inspect some of the high-technology stops built by Enel X, as a way of experiencing the route as passengers will. The project includes the implementation of 40 bus stops, which offer users a range of new services such as LED lighting, bicycle parking, information panels, and USB charging ports. The ride ended at Peñalolén electric bus terminal, where the opening ceremony was held in the presence of guests such as President Sebastián Piñera, Transport Minister Gloria Hutt, Enel Chile chairman Herman Chadwick, Enel Chile CEO Paolo Pallotti, Enel X Chile CEO Karla Zapata, Metbus chairman Juan Pinto, and BYD country manager for Chile Tamara Berríos. -

Sostenibilidad Urbana En La Comuna De Santiago De Chile

AE-OBSV. Observatorios de Sostenibilidad. Iniciativas Españolas e Iberoamericanas SOSTENIBILIDAD URBANA EN LA COMUNA DE SANTIAGO DE CHILE Néstor Ahumada Galaz Técnico Asesoría Urbana ASESORÍA URBANA MUNICIPALIDAD DE SANTIAGO DE CHILE www.conama9.org Sostenibilidad Urbana en la Comuna de Santiago de Chile Néstor Ahumada Galaz Geógrafo I. Municipalidad de Santiago Asesoría Urbana Santiago en el continente Región Metropolitana en el contexto nacional Chile en el Contexto Sudamericano Superficie continental: 816.260 Km2 Capital: Santiago, ubicada en la Región Metropolitana Superficie territorio antártico: 1.250.000 km2 Población: 15.116.435 de habitantes (aprox.) Superficie Región Metropolitana: 15.403 km2 Regiones: 13 Población de la ciudad de Santiago (R M): 6.061.185. Santiago Metropolitano Evolución 1541 1600 1900 1920 1940 1952 1960 1970 1980 1996 2004 Antecedentes generales 2005 COMUNA DE SANTIAGO Superficie : 2.320 há. QU ILI CU RA HUECHURABA VI TAC URA Población : 200.792 hab. CONCHALI RENCA Densidad : 99.5 hab/há. RECOLETA LAS CONDES INDEPENDENCIA CERRO NAVIA Población flotante: 1.800.000 QUINTA NORMAL PR OVID EN CI A PU DAH UEL LO PRADO LA REI NA SANTIAGO CENTRO FINANCIERO Y NUNOA EST C ENTR AL COMERCIAL PENALOLEN P AGUIRRE C MACUL SAN JOAQUIN Sede de las casas matrices de CERRILLOS MAIPU SAN M IGUEL bancos y financieras y de la LO ESPEJO Bolsa de Comercio LA CISTERNA LA FLORI DA SAN RAMONLA GRANJ A - 61% colocaciones bancarias EL BOSQUE - 56% depósitos y captaciones bancarias PUENTE ALTO LA PIN TANA CENTRO DE EDUCACION SAN BERNARDO - 25% de la matrícula de educación superior a escala nacional CENTRO DE CULTURA SEDE DEL PODER POLITICO Actividades hacia la sostenibilidad Certificación Ambiental El municipio de Santiago ha trabajando desde el año 2005 en el “Sistema Nacional de Certificación Ambiental de Establecimientos Educacionales”, iniciativa impulsada por organismos del gobierno central en pos de fortalecer la educación ambiental. -

Atmchile: Download Air Quality and Meteorological Information of Chile

Package ‘AtmChile’ August 18, 2021 Type Package Title Download Air Quality and Meteorological Information of Chile Version 0.2.0 Maintainer Francisco Catalan Meyer <[email protected]> Description Download air quality and meteorological information of Chile from the Na- tional Air Quality System (S.I.N.C.A.)<https://sinca.mma.gob.cl/> dependent on the Min- istry of the Environment and the Meteorological Direc- torate of Chile (D.M.C.)<http://www.meteochile.gob.cl/> dependent on the Direc- torate General of Civil Aeronautics. License GPL-3 URL https://github.com/franciscoxaxo/AtmChile Encoding UTF-8 LazyData false RoxygenNote 7.1.1 Imports data.table, plotly, shiny, openair, lubridate, shinycssloaders, DT NeedsCompilation no Author Francisco Catalan Meyer [aut, cre] (<https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3506-5376>), Manuel Leiva [aut] (<https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8891-0399>), Richard Toro [aut] Repository CRAN Date/Publication 2021-08-18 16:50:02 UTC R topics documented: ChileAirQuality . .2 ChileAirQualityApp . .3 ChileClimateData . .4 Index 5 1 2 ChileAirQuality ChileAirQuality ChileAirQuality Description function that compiles air quality data from the National Air Quality System (S.I.N.C.A.) Usage ChileAirQuality( Comunas = "INFO", Parametros, fechadeInicio, fechadeTermino, Site = FALSE, Curar = TRUE, st = FALSE ) Arguments Comunas data vector containing the names or codes of the monitoring stations. Available stations: "P. O’Higgins","Cerrillos 1","Cerrillos","Cerro Navia", "El Bosque","Independecia","La Florida","Las Condes","Pudahuel","Puente Alto","Quilicura", "Quilicura 1","Alto Hospicio","Arica","Las Encinas Temuco","Nielol Temuco", "Museo Ferroviario Temuco","Padre Las Casas I","Padre Las Casas II","La Union", "CESFAM Lago Ranco","Mafil","Fundo La Ribera","Vivero Los Castanos","Valdivia I", "Val- divia II","Osorno","Entre Lagos","Alerce","Mirasol","Trapen Norte","Trapen Sur", "Puerto Varas","Coyhaique I","Coyhaique II","Punta Arenas". -

Plan Regulador Comunal De Quinta Normal Región Metropolitana

PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL QUINTA NORMAL REGIÓN METROPOLITANA PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL DE QUINTA NORMAL REGIÓN METROPOLITANA MEMORIA EXPLICATIVA TOMO I SEPTIEMBRE 2019 PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL QUINTA NORMAL REGIÓN METROPOLITANA SEPTIEMBRE 2019 PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL QUINTA NORMAL REGIÓN METROPOLITANA ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS 1 ANTECEDENTES...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 ANTECEDENTES GENERALES ...................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 ANTECEDENTES HISTÓRICOS ...................................................................................... 1-4 2 ESTRUCTURA URBANA .......................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 LA COMUNA EN EL CONTEXTO METROPOLITANO E INTERCOMUNAL .................... 2-2 2.1.1 Tendencias de desarrollo urbano y su efecto en la Comuna ........................................ 2-2 2.1.2 Obras urbanas y viales y su impacto en la Comuna ..................................................... 2-7 2.1.3 Quinta Normal y sus comunas vecinas ....................................................................... 2-11 3 ANÁLISIS DE LA NORMATIVA VIGENTE ................................................................................ 3-1 3.1 PLAN REGULADOR METROPOLITANO DE SANTIAGO ................................................ 3-1 3.1.1 Zonificación y normas .................................................................................................. -

PROCEDIMIENTO Xxxxxxxxxxxxx

EMPRESA DE TRANSPORTE DE PASAJEROS METRO GERENCIA CORPORATIVA DE INGENIERÍA SERVICIO DE MONITOREO DE RUIDO ETAPA DE CONSTRUCCIÓN LINEA 7 METRO DE SANTIAGO TÉRMINOS DE REFERENCIA 0 07-03-2021 Emitido para uso B 10-12-2020 Revisión Interna A 27-11-2020 Revisión Interna Subgerencia de Medioambiente REV FECHA EMITIDO PARA ELABORADO POR REVISADO POR APROBADO POR PCL AMG-JAC GRB Página 1 de 25 L7-C17005-NR-0-7CO-TDR-0001 Rev. 0 Rev. 0 TÉRMINOS DE REFERENCIA 07-03-2021 INDICE 1 ANTECEDENTES GENERALES DEL PROYECTO Y DE LA CONSULTORÍA A LICITAR ... 3 1.1 Presentación del Proyecto ............................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Presentación del Servicio a Cotizar ............................................................................................ 4 1.3 Objetivo ................................................................................................................................................ 4 2 ALCANCE DE LA CONSULTORÍA ..................................................................................... 5 2.1 Monitoreo de Ruido Mensual a Obras de Construcción.................................................... 6 2.2 De los Reportes e Informes ......................................................................................................... 12 2.3 Instalaciones del Consultor ......................................................................................................... 15 3 PERSONAL Y EQUIPAMIENTO MÍNIMO REQUERIDO ............................................... -

Índice De Prioridad Social De Comunas 2020 RM

REGIÓN METROPOLITANA DE SANTIAGO ÍNDICE DE PRIORIDAD SOCIAL DE COMUNAS 2020 Seremi de Desarrollo Social y Familia Metropolitana Documento elaborado por: Santiago Gajardo Polanco Área de Estudios e Inversiones Seremi de Desarrollo Social y Familia R.M. Santiago, enero 2021 Secretaría Regional Ministerial de Desarrollo Social y Familia Región Metropolitana de Santiago INDICE 2 PRESENTACIÓN 3 INTRODUCCION 4 I. DIMENSIONES E INDICADORES DEL INDICE DE PRIORIDAD SOCIAL 5 (IPS) 1.1. Dimensión Ingresos 5 1.1.1. Porcentaje de población comunal perteneciente al 40% de menores ingresos de 5 la Calificación Socioeconómica 1.1.2. Ingreso promedio imponible de los afiliados vigentes al Seguro de Cesantía 5 1.2. Dimensión Educación 6 1.2.1. Resultados de la Prueba SIMCE de los 4º años básicos 6 1.2.2. Resultados Prueba PSU 6 1.2.3. Porcentaje de Reprobación en la Enseñanza Media 6 1.3. Dimensión Salud 7 1.3.1. Tasa de años de vida potencialmente perdidos por habitante (TAVPP) entre 0 y 7 80 años 1.3.2. Tasa de fecundidad específica de mujeres entre 15 y 19 años 7 1.3.3. Porcentaje niños y niñas menores de 6 años en situación de malnutrición 7 II. METODOLOGÍA DE CONSTRUCCIÓN DEL ÍNDICE 9 III. RESULTADOS 10 ANEXOS 15 2 Secretaría Regional Ministerial de Desarrollo Social y Familia Región Metropolitana de Santiago PRESENTACIÓN La Secretaría Regional Ministerial de Desarrollo Social y Familia de la Región Metropolitana de Santiago reconoce como una de sus funciones importantes el desarrollo de instrumentos que apoyen la toma de decisiones por parte de los diversos servicios y autoridades regionales y comunales. -

Descentralización Y Democracia En Chile: Análisis Sobre La Participación Ciudadana En El Presupuesto Participativo Y El Plan De Desarrollo Comunal

revista dedescentralización ciencia pOlítica / vyO participaciónluMen 26 / nº 2ciudadana / 2006 / 191 en chile– 208 DESCENTRALIZACIÓN Y DEMOCRACIA EN CHILE: ANÁLISIS SOBRE LA PARTICIPACIÓN CIUDADANA EN EL PRESUPUESTO PARTICIPATIVO Y EL PLAN DE DESARROLLO COMUNAL Egon MontEcinos UnivErsidad dE Los Lagos, chile resumen este estudio aporta evidencia al supuesto de que la profundización de la participación ciudadana en la gestión municipal no depende únicamente de mayores transferencias provistas por los niveles centrales de gobierno o de incentivos externos a nivel municipal, sino que también está relacionada con un cambio cualitativo en la forma de hacer gestión en el espacio local. cuando este cambio se produce desde ese nivel, pueden lograrse iniciativas profundas de participación ciudadana. la estrategia metodológica utilizada fue un estudio comparado sobre la participación ciudadana que se produjo en los planes de desarrollo comunal y en los presupuestos participativos. los casos seleccionados fueron illapel, cerro navia, san Joaquín, Buin y negrete. abstract this paper contributes evidence to the premiss that the deepening of citizen participation in municipal management does not only depend on greater transfers from central government’s levels or external incentives at municipal levels, but is also related to a qualitative change in municipal management in the local space. When this change takes place on a local level, deep initiatives of citizen participation can be achieved. the methodological strategy used was a comparative study on citizen participation in communal development plans and participatory budgets. the selected cases were illapel, cerro navia, san Joaquín, Buin and negrete. palaBras clave • participación ciudadana • Gestión municipal • descentralización I. INTRODUCCIÓN entre los estudios sobre la dinámica política de la descentralización se pueden distinguir dos tendencias que se plantean diferentes preguntas e hipótesis de investigación. -

Supplement of Nat

Supplement of Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 20, 1533–1555, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-20-1533-2020-supplement © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of Contrasting seismic risk for Santiago, Chile, from near-field and distant earthquake sources Ekbal Hussain et al. Correspondence to: Ekbal Hussain ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. 71.0°W 70.0°W 1. Santiago 2. 3. 4. Providencia 33.0°S 5. 6. 7. San Joaquin 8. 9. Pedro Aguirre Cerda 10. 11. Quinta Normal 32 31 12. 30 13 3 29 13. Conchali 12 2 14 11 4 14. Cerro Navia 15 28 10 1 5 15. 27 16 9 8 7 6 16. Cerrillos 17 18 22 26 21 17. Lo Espejo 33 19 18. 20 25 23 19. 24 20. La Pintana 21. San Ramon 22. La Granja 23. 24. Calera de Tango 25. 26. 27. Penalolen 28. 29. Las Condes 30. 31. Huechuraba 34.0°S 33.5°S 32. 33. 0 10 20 30 40 km 71.0°W 70.0°W Figure S1. Map showing the communes of the Santiago Metropolitan Region and the distribution of the residential building exposure model used in the risk calculations. The exposure model is downsampled to a 1×1 km grid from Santa-María et al. (2017). The red lines indicate the surface trace of the San Ramón fault used in the seismic risk scenario calculations, and the dashed cyan the buried fault splay.