Cop14 Prop. 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalbergia Proposal Guatemala (Rev.2)

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA CONSIDERATION OF PROPOSALS FOR AMENDMENT OF APPENDICES I AND II A. Proposal Inclusion of the genus Dalbergia in CITES Appendix II with exception to the species included in Appendix I. The UNEP-WCMC assessed the Dalbergia species of Latin America and concluded: “… all populations of Dalbergia spp. from South and Central America appear to meet the criteria for listing in CITES Appendix II” (UNEP-WCMC, 2015). Including the whole genus in Appendix II will be essential for the control of international trade by eliminating the arduous task of enforcement and customs officers of differentiating between the hundreds of Dalbergia species listed and not listed in CITES. The inclusion will help ensure that legal trade does not become a direct cause of the extinction of these highly threatened species and will help curb illegal trade. Considering that CITES Appendix II must include all species, which although not necessarily now threatened with extinction may become so unless trade in specimens of such species is subject to strict regulation in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival, it is important to include the genus Dalbergia in CITES Appendix II. a) Resolution Conf. 9.24, Annex 2 a, Criterion A - ”It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that the regulation of trade in the species is necessary to avoid it becoming eligible for inclusion in Appendix I in the near future”. b) Resolution Conf. 9.24, Annex 2 a, Criterion B - ”It is known, or can be inferred or projected, that regulation of trade in the species is required to ensure that the harvest of specimens from the wild is not reducing the wild population to a level at which its survival might be threatened by continued harvesting or other influences”. -

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID. The project has been financed by the CITES Secretariat with funds from the European Union Consulting objectives: TO SELECT INTERNATIONAL OR NATIONAL XYLARIUM OR WOOD COLLECTIONS REGISTERED AT THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WOOD ANATOMISTS – IAWA THAT HAVE A SIGNIFICANT NUMBER OF SPECIES AND SPECIMENS OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA TO BE ANALYZED BY NIRS TECHNOLOGY. Consultant: VERA TERESINHA RAUBER CORADIN Dra English translation: ADRIANA COSTA Dra Affiliations: - Forest Products Laboratory, Brazilian Forest Service (LPF-SFB) - Laboratory of Automation, Chemometrics and Environmental Chemistry, University of Brasília (AQQUA – UnB) - Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC-DF MAY, 2020 Brasília – Brazil 1 Project number: S1-32QTL-000018 Host Country: Brazilian Government Executive agency: Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC Project coordinator: Dra. Tereza C. M. Pastore Project start: September 2019 Project duration: 24 months 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 05 2. THE SPECIES OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA 05 3. MATERIAL AND METHODS 3.1 NIRS METHODOLOGY AND SPECTRA COLLECTION 07 3.2 CRITERIA FOR SELECTING XYLARIA TO BE VISITED TO OBTAIN SPECTRAS 07 3 3 TERMINOLOGY 08 4. RESULTS 4.1 CONTACTED XYLARIA FOR COLLECTION SURVEY 10 4.1.1 BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 10 4.1.2 INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 11 4.2 SELECTED XYLARIA 11 4.3 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 13 4.4 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 14 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 19 6. REFERENCES 20 APPENDICES 22 APPENDIX I DALBERGIA IN BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 22 CACAO RESEARCH CENTER – CEPECw 22 EMÍLIO GOELDI MUSEUM – M. -

Cocobolo Samuel J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Yale University Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Bulletin Series 1923 Cocobolo Samuel J. Record George A. Garratt Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_bulletin Part of the Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, and the Wood Science and Pulp, Paper Technology Commons Recommended Citation Record, Samuel J., and George A. Garratt. 1923. ocC obolo. Yale School of Forestry Bulletin 8. 42 pp. + plates This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Note to Readers 2012 This volume is part of a Bulletin Series inaugurated by the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in 1912. The Series contains important original scholarly and applied work by the School’s faculty, graduate students, alumni, and distinguished collaborators, and covers a broad range of topics. Bulletins 1-97 were published as bound print-only documents between 1912 and 1994. Starting with Bulletin 98 in 1995, the School began publishing volumes digitally and expanded them into a Publication Series that includes working papers, books, and reports as well as Bulletins. -

Stay Sharp B Ill Carroll

r 72 gt a hadl o kif akig ad stay sharp y ill carroll Knife making has become a popular endeavor for woodworkers of all skill levels. This beginner’s guide will get you started. { no. 59 } rom cutting and marking in the Fshop, to hunting and camping, to preparing a simple meal, a good knife is indispensable. Mass-produced knives gt a hadl o kif akig ad can be found for every budget and use. But custom knives, which are often far more attractive, tend to get expensive very quickly. stay sharp Of course, the ultimate custom 1 2 knife would include a hand-forged and hand-sharpened blade. If you’re not up for the expense and dirty work of such an endeavor, you can still experience the pride of a well-crafted and functional addition to your tool collection. All you need is a knife kit. It’s all in there 3 4 A knife kit consists of a prefabricated blade and pins, which allows the maker to select handle materials, assemble Select wood for your scales and the knife, and shape and polish it to determine which sides will face away perfection. It requires minimal tools, from the handle portion of the knife good attention to aesthetic detail and blank, or the “tang.” Using the blank, a few hours of shop time. Once you’ve trace the shape of the tang onto each gained some knife-making experience, scale (Fig. 3). Make sure to trace the there are hundreds of types of knives tang in the proper orientation to keep (and swords, and spears) available as the best woodgrain on the visible 5 kits from a number of sources. -

10-Inch Drum Sander

10-INCH DRUM SANDER For replacement parts visit Model # 65910 WENPRODUCTS.COM bit.ly/wenvideo IMPORTANT: Your new tool has been engineered and manufactured to WEN’s highest standards for dependability, ease of operation, and operator safety. When properly cared for, this product will supply you years of rugged, trouble-free performance. Pay close attention to the rules for safe operation, warnings, and cautions. If you use your tool properly and for its intended purpose, you will enjoy years of safe, reliable service. NEED HELP? CONTACT US! Have product questions? Need technical support? Please feel free to contact us at: 800-232-1195 (M-F 8AM-5PM CST) [email protected] WENPRODUCTS.COM NOTICE: Please refer to wenproducts.com for the most up-to-date instruction manual. TABLE OF CONTENTS Technical Data 2 Safety Introduction 3 General Safety Rules 4 Electrical Information 6 Specific Rules for Drum Sanders 7 Know Your Drum Sander 8 Unpacking 9 Assembly 10 Preparation 14 Operation 18 Adjustments 19 Maintenance 22 Troubleshooting 24 Exploded View and Parts List 26 Warranty Statement 30 TECHNICAL DATA Model Number: 65910 Motor: 120V, 60Hz, 10.5A Drum Speed: 1440 RPM Sandpaper Speed: 2300 FPM Conveyor Feed Speed: 0 to 10 FPM Maximum Workpiece Width: 9-1/2 in. (240mm) Minimum Workpiece Width: 3/4 in. (19mm) Maximum Workpiece Height: 3 in. (75mm) Minimum Workpiece Height: 1/4 in. (6mm) Minimum Workpiece Length 4-3/4 in. (120mm) Sandpaper Width: 3 in. Sandpaper Length: 62-1/2 in. Sanding Drum Size: 5-1/8 x 10 in. (132 x 255mm) Dust Port Diameter: 3.9 in. -

Panama’S Illegal Rosewood Logging Boom from Dalbergia Retusa

Global Ecology and Conservation 23 (2020) e01098 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Panama’s illegal rosewood logging boom from Dalbergia retusa * Ella Vardeman a, b, d, , Julie Velasquez Runk a, c a University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30602, USA b City University of New York, Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave, New York, NY, 10016, USA c Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panama d The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), Institute of Economic Botany, 2900 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, NY 10458, USA article info abstract Article history: Over the last decade, illegal rosewood logging has surged worldwide, with much attrib- Received 9 December 2019 utable to an uptick in Chinese demand. For the last seventy-five years, Panama’s main use Received in revised form 30 April 2020 of cocobolo rosewood (Dalbergia retusa) was in small pieces for artisanal carvings, its state Accepted 30 April 2020 of conservation favoring merchantable timber for recent exploitation with the surging market. Panama’s cocobolo rosewood boom was from 2011 to 2015 and, given regulations, Keywords: was largely illicit. However, no data on cocobolo logging have been made public. Here, we Dalbergia retusa assess Panama’s cocobolo logging. We used a media analysis of Panamanian and inter- Panama Media analysis national reports on cocobolo logging from January 2000 to February 2018 coupled with Illegal logging long-term socio-environmental research to show how logging changed during the boom. We conducted a content analysis of articles to address four specific objectives: 1) to assess how cocobolo logging intensity changed over time; 2) to determine what topics related to logging were important for the press to relay to the public; 3) to show how logging changed geographically as the boom progressed; 4) to demonstrate how Panama and the international community responded to the global boom with new policies on rosewood governance. -

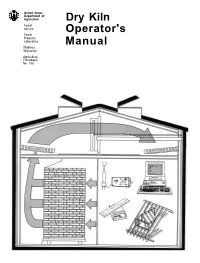

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples. -

Chapter 3--Physical Properties and Moisture Relations of Wood

Chapter 3 Physical Properties and Moisture Relations of Wood William Simpson and Anton TenWolde he versatility of wood is demonstrated by a wide Contents variety of products. This variety is a result of a Appearance 3–1 spectrum of desirable physical characteristics or properties among the many species of wood. In many cases, Grain and Texture 3–1 more than one property of wood is important to the end Plainsawn and Quartersawn 3–2 product. For example, to select a wood species for a product, the value of appearance-type properties, such as texture, grain Decorative Features 3–2 pattern, or color, may be evaluated against the influence of Moisture Content 3–5 characteristics such as machinability, dimensional stability, Green Wood and Fiber Saturation Point 3–5 or decay resistance. Equilibrium Moisture Content 3–5 Wood exchanges moisture with air; the amount and direction of the exchange (gain or loss) depend on the relative humid- Sorption Hysteresis 3–7 ity and temperature of the air and the current amount of water Shrinkage 3–7 in the wood. This moisture relationship has an important Transverse and Volumetric 3–7 influence on wood properties and performance. This chapter discusses the physical properties of most interest in the Longitudinal 3–8 design of wood products. Moisture–Shrinkage Relationship 3–8 Some physical properties discussed and tabulated are influ- Weight, Density, and Specific Gravity 3–11 enced by species as well as variables like moisture content; Working Qualities 3–15 other properties tend to be independent of species. The thor- oughness of sampling and the degree of variability influence Decay Resistance 3–15 the confidence with which species-dependent properties are Thermal Properties 3–15 known. -

Woodworking Glossary, a Comprehensive List of Woodworking Terms and Their Definitions That Will Help You Understand More About Woodworking

Welcome to the Woodworking Glossary, a comprehensive list of woodworking terms and their definitions that will help you understand more about woodworking. Each word has a complete definition, and several have links to other pages that further explain the term. Enjoy. Woodworking Glossary A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | #'s | A | A-Frame This is a common and strong building and construction shape where you place two side pieces in the orientation of the legs of a letter "A" shape, and then cross brace the middle. This is useful on project ends, and bases where strength is needed. Abrasive Abrasive is a term use to describe sandpaper typically. This is a material that grinds or abrades material, most commonly wood, to change the surface texture. Using Abrasive papers means using sandpaper in most cases, and you can use it on wood, or on a finish in between coats or for leveling. Absolute Humidity The absolute humidity of the air is a measurement of the amount of water that is in the air. This is without regard to the temperature, and is a measure of how much water vapor is being held in the surrounding air. Acetone Acetone is a solvent that you can use to clean parts, or remove grease. Acetone is useful for removing and cutting grease on a wooden bench top that has become contaminated with oil. Across the Grain When looking at the grain of a piece of wood, if you were to scratch the piece perpendicular to the direction of the grain, this would be an across the grain scratch. -

Fplgtr113.Pdf

Abstract Summarizes information on wood as an engineering material. Presents properties of wood and wood-based products of particular concern to the architect and engineer. Includes discussion of designing with wood and wood-based products along with some pertinent uses. Keywords: wood structure, physical properties (wood), mechanical properties (wood), lumber, wood-based composites, plywood, panel products, design, fastenings, wood moisture, drying, gluing, fire resistance, finishing, decay, sandwich construction, preservation, and wood- based products On the cover: (Left to right, top to bottom) 1. Research at the Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin, contributes to maximizing benefits of the Nation’s timber resource. 2. Testing the behavior of wood in fire helps enhance fire safety. 3. The all-wood, 162-m (530-ft ) clear-span Tacoma Dome exemplifies the structural and esthetic potential of wood construction (photo courtesy of Western Wood Structures, Inc., Tualatin, Oregon). 4. Bending tests are commonly used to determine the engineering properties of wood. 5. Engineered wood trusses exemplify research that has led to more efficient use of wood. 6. The Teal River stress-laminated deck bridge is March 1999 located in Sawyer County, Wisconsin. 7. Kiln drying of wood is an important procedure Forest Products Laboratory. 1999. Wood handbook—Wood as an during lumber manufacturing. engineering material. Gen. Tech. Rep. FPL–GTR–113. Madison, WI: 8. Legging adhesive (photo courtesy of Air Products U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products and Chemicals, Inc., Allentown Pennsylvania). Laboratory. 463 p. Adhesive bonding is a critical component in the A limited number of free copies of this publication are available to the performance of many wood products. -

Leguminosae Cocobolo

Dalbergia retusa Family: Leguminosae Cocobolo Other Common Names: Granadillo (Mexico, Guatemala), Funera (El Salvador), Palo negro (Honduras), Nambar (Nicaragua, Costa Rica), Cocobolo, Cocobolo prieto (Panama). Distribution: Pacific regions of Central America and extending from Panama to southwestern Mexico. Of limited occurrence, usually in the drier uplands. The Tree: A small to medium-sized tree 45 to 60 ft high with trunk diameters of 20 to 24 in.; usually of poor form. The Wood: General Characteristics: Somewhat variable in color when freshly sawn but heartwood usually becoming a deep rich orange red with black striping or mottling on exposure Texture fine; grain straight to interlocked; oily; without distinctive taste, odor slightly pungent and fragrant when worked. Fine dust may cause dermatitis. Weight: Basic specific gravity (ovendry weight/green volume) 0.80 to 0.98; air- dry density 62 to 76 pcf. Mechanical Properties: No data available, but is denser and stronger than Brazilian rosewood (see D. nigra). Drying and Shrinkage: Reported to have excellent drying properties, free of surface and end checking. A kiln schedule similar to T1-B1 has been suggested. Shrinkage is usually low; high stability in use. Very low moisture absorption. Working Properties: Reported to have excellent machining characteristics; natural oils give the wood a good polish, but make it unsuitable for gluing. Fine dust may produce rash resembling ivy poisoning. Durability: Durability is high, has very high resistance to marine borer attack. Preservation: No data available. Uses: Highly favored in the cutlery trade for handles, inlay work, brush backs, musical and scientific instruments, jewelry boxes, chessmen, and other specialty items. -

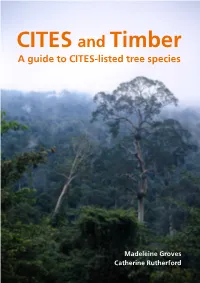

CITES and Timber (PDF)

This guide covers the main timber species regulated CITES and Timber by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). It provides information CITES and Timber on the key issues regarding the implementation of the Convention for this important group of plants. A guide to CITES-listed tree species Written for the non-expert, individual sections cover the species found in significant trade, with details on their distribution, uses, traded parts and derivatives, and scientific and common names. Madeleine Groves Madeleine Groves Additional sections cover timber identification and measurement, guidance on CITES documentation and key resources. and Catherine Rutherford shop.kew.org/kewbooksonline Madeleine Groves Catherine Rutherford CITES and Timber A guide to CITES-listed tree species Madeleine Groves Catherine Rutherford © The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2015 Illustrations and photographs © Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, unless otherwise stated in the captions The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher unless in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988. Great care has been taken to maintain the accuracy of the information contained in this work. However, neither the publisher, the editors nor authors can be held responsible for any consequences arising from use of the information contained herein.