Artisanal Non-Timber Forest Products in Darién Province, Panamá: the Importance of Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palmoxylon Phytelephantoides Sp.Nov.- a New Fossil Palm from the Deccan Intertrappean Beds of Umaria, Madhya Pradesh, India

International Journal of Advanced Scientific Research and Management, Volume 4 Issue 6, June 2019 www.ijasrm.com ISSN 2455-6378 Palmoxylon phytelephantoides sp.nov.- A New Fossil Palm from the Deccan Intertrappean Beds of Umaria, Madhya Pradesh, India 1 2 3 S.V. Chate , S.D. Bonde , P.G. Gamre 1Department of Botany, Shivaji Mahavidyalaya Udgir, Dist-Latur, Maharashtra, India. 2,3 Palaeobiology Division,Agharkar Research Institute, Pune, Maharashtra,India. Abstract monocotyledons, the Arecaceae shows by far the The present paper deals with a new petrified palm richest fossil record, and there is an extensive stem having root matrix under the organ genus literature available. Though, fossil material often Palamoxylon (Palmoxylon phytelephantoides lacks sufficient diagnostic detail to allow reasonable association with living palm taxa beyond, or even to, sp. nov.) from Deccan Intertrappean Beds of subfamilial level. However, many fossil genera and Umaria, Madhya Pradesh, India with its numerous species have been described. phytogeographical significance. Detailed anatomical Umaria is one of the well-known plant fossil locality investigations suggest its resemblance with the belongs to Deccan Intertrappean beds which have Phytelephantoid palm, Phytelephas Ruiz & Pavon. been dated 65 million years old (Krishnan, Occurrence of fossils of Phytelephas in the Deccan Intertrappean beds of India and their present 1973). Fossils are scattered and widely spread over distribution in South America and Panama has a in a large area of Umaria, Dindori and Mandla phytogeographical significance. Fossil stem of districts of Madhya Pradesh, India. Records of Phytelephas (P. sewardii) and a seed (P. olssoni fossils, including a large number of plant organs such Brown,) has been reported from Central America as roots, stems, leaves, rhizomes, fruits, seeds, and where extant Phytelephas grows naturally. -

Pollination of Cultivated Plants in the Tropics 111 Rrun.-Co Lcfcnow!Cdgmencle

ISSN 1010-1365 0 AGRICULTURAL Pollination of SERVICES cultivated plants BUL IN in the tropics 118 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO 6-lina AGRICULTUTZ4U. ionof SERNES cultivated plans in tetropics Edited by David W. Roubik Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Balboa, Panama Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations F'Ø Rome, 1995 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-11 ISBN 92-5-103659-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. FAO 1995 PlELi. uion are ted PlauAr David W. Roubilli (edita Footli-anal ISgt-iieulture Organization of the Untled Nations Contributors Marco Accorti Makhdzir Mardan Istituto Sperimentale per la Zoologia Agraria Universiti Pertanian Malaysia Cascine del Ricci° Malaysian Bee Research Development Team 50125 Firenze, Italy 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Stephen L. Buchmann John K. S. Mbaya United States Department of Agriculture National Beekeeping Station Carl Hayden Bee Research Center P. -

![Hyphaene Petersiana Klotzsch Ex Mart. [ 1362 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3448/hyphaene-petersiana-klotzsch-ex-mart-1362-313448.webp)

Hyphaene Petersiana Klotzsch Ex Mart. [ 1362 ]

This report was generated from the SEPASAL database ( www.kew.org/ceb/sepasal ) in August 2007. This database is freely available to members of the public. SEPASAL is a database and enquiry service about useful "wild" and semi-domesticated plants of tropical and subtropical drylands, developed and maintained at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. "Useful" includes plants which humans eat, use as medicine, feed to animals, make things from, use as fuel, and many other uses. Since 2004, there has been a Namibian SEPASAL team, based at the National Botanical Research Institute of the Ministry of Agriculture which has been updating the information on Namibian species from Namibian and southern African literature and unpublished sources. By August 2007, over 700 Namibian species had been updated. Work on updating species information, and adding new species to the database, is ongoing. It may be worth visiting the web site and querying the database to obtain the latest information for this species. Internet SEPASAL New query Edit query View query results Display help In names list include: synonyms vernacular names and display: 10 names per page Your query found 1 taxon Hyphaene petersiana Klotzsch ex Mart. [ 1362 ] Family: PALMAE Synonyms Hyphaene benguellensis Welw. Hyphaene benguellensis Welw. var. plagiocarpa (Dammer)Furtado Hyphaene benguellensis Welw. var. ventricosa (Kirk)Furtado Hyphaene ventricosa J.Kirk Vernacular names (East Africa) [nuts] dum [ 2357 ] (Zimbabwe) murara [ 3023 ], ilala [ 3030 ] Afrikaans (Namibia) makalanie-palm [ 5083 -

Cocobolo Samuel J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Yale University Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Bulletin Series 1923 Cocobolo Samuel J. Record George A. Garratt Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_bulletin Part of the Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, and the Wood Science and Pulp, Paper Technology Commons Recommended Citation Record, Samuel J., and George A. Garratt. 1923. ocC obolo. Yale School of Forestry Bulletin 8. 42 pp. + plates This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Note to Readers 2012 This volume is part of a Bulletin Series inaugurated by the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in 1912. The Series contains important original scholarly and applied work by the School’s faculty, graduate students, alumni, and distinguished collaborators, and covers a broad range of topics. Bulletins 1-97 were published as bound print-only documents between 1912 and 1994. Starting with Bulletin 98 in 1995, the School began publishing volumes digitally and expanded them into a Publication Series that includes working papers, books, and reports as well as Bulletins. -

GALLEY 66 File # 10Em

ECONOMIC BOTANY Wednesday Jan 14 2004 01:03 PM ebot 58_110 Mp_66 Allen Press x DTPro System GALLEY 66 File # 10em CONSERVATION OF USEFUL PLANTS:AN EVALUATION OF LOCAL PRIORITIES FROM TWO INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES IN EASTERN PANAMA1 SARAH PAULE DALLE AND CATHERINE POTVIN Dalle, Sarah Paule (Department of Plant Science, Macdonald Campus of McGill University, 21111 Lakeshore Dr., Ste-Anne-de-Bellevue, QueÂbec, Canada H9X 3V9; e-mail: sar- [email protected]) and Catherine Potvin (Biology Department, McGill University, 1205 ave Dr. Pen®eld, MontreÂal, QueÂbec, Canada H3A 1B1). CONSERVATION OF USEFUL PLANTS:AN EVALUATION OF LOCAL PRIORITIES FROM TWO INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES IN EASTERN PANAMA. Economic Botany 58(1):000±000, 2004. On both theoretical and practical grounds, respect for, and inclusion of, local decision-making processes is advocated in conservation, yet little is known about the conservation priorities on local territories. We employed interviews and eco- logical inventories in two villages in order to (1) evaluate the local perception of the conser- vation status of important plant resources; (2) compare patterns of plant use; and (3) compare perceived conservation status with population structure and abundance in the ®eld. One-third of the 35 species examined were perceived to be threatened or declining. These were predom- inantly used locally for construction or sold commercially, but were not necessarily rare in the ®eld. The destructiveness of harvest was the most consistent predictor of conservation status in both villages. Contrasting patterns were found in the two villages for the frequency of plant harvest and the relationship of this variable with conservation status. -

Stay Sharp B Ill Carroll

r 72 gt a hadl o kif akig ad stay sharp y ill carroll Knife making has become a popular endeavor for woodworkers of all skill levels. This beginner’s guide will get you started. { no. 59 } rom cutting and marking in the Fshop, to hunting and camping, to preparing a simple meal, a good knife is indispensable. Mass-produced knives gt a hadl o kif akig ad can be found for every budget and use. But custom knives, which are often far more attractive, tend to get expensive very quickly. stay sharp Of course, the ultimate custom 1 2 knife would include a hand-forged and hand-sharpened blade. If you’re not up for the expense and dirty work of such an endeavor, you can still experience the pride of a well-crafted and functional addition to your tool collection. All you need is a knife kit. It’s all in there 3 4 A knife kit consists of a prefabricated blade and pins, which allows the maker to select handle materials, assemble Select wood for your scales and the knife, and shape and polish it to determine which sides will face away perfection. It requires minimal tools, from the handle portion of the knife good attention to aesthetic detail and blank, or the “tang.” Using the blank, a few hours of shop time. Once you’ve trace the shape of the tang onto each gained some knife-making experience, scale (Fig. 3). Make sure to trace the there are hundreds of types of knives tang in the proper orientation to keep (and swords, and spears) available as the best woodgrain on the visible 5 kits from a number of sources. -

Jarina (Phytelephas Macrocarpa Ruiz & Pav. )

Jarina (Phytelephas macrocarpa Ruiz & Pav. ) As sementes amadurecidas tornam-se duras, brancas e opacas como o marfim, com a vantagem de não ser quebradiça e fácil de ser Nome científico:Phytelephas macrocarpa Ruiz & Pav. trabalhada. A coleta das sementes ocorre em grande quantidade entre os meses de maio e agosto, sendo a regeneração natural aleatória. Sinonímia:Elephantusia macrocarpa (Ruiz & Pav.) Willd.; Phytelephas Parte da planta utilizada: A palmeira é utilizada por populações locais microcarpa(Ruiz & Pav.); Elephantusia microcarpa (Ruiz & Pav.) Willd.; na construção civil (cobertura de casas com as folhas), alimentação do Yarina microcarpa (Ruiz & Pav.) O. F. Cook. homem e animais (polpa não amadurecida) e confecções de cordas (fibras). Contudo, a parte mais usada da planta é a semente, que em Espécies: P. macrocarpa (na Amazônia brasileira, boliviana e peruana), substituição ao marfim animal, é empregada na confecção de P. tenuicaulis(na Amazônia equatoriana e colombiana), P. schotii (no ornamentos, botões, peças de joalheria, teclas de piano, pequenas vale de Magdalena, Colombia),P. seemanii (América Central e lado estatuetas e vários souvenirs. As sobras da jarina são transformadas colombiano do Pacífico),P. aequatoriales e P. tumacana (na região em um pó, que é exportado do Equador para os Estados Unidos e Pacífica do Equador e Colômbia). Japão, após o corte do material para a produção de botões. Família botânica: Arecaceae. Aspectos agronômicos: ainda não se dispõe de informações acerca de plantios experimentais de P. macrocarpa. As poucas plantas cultivadas Nomes populares: "marfim vegetal", em português; tagua em espanhol; podem ser encontradas em jardins públicos e particulares com função ivory plant, em inglês e Brazilianische steinmüssee, em alemão. -

10-Inch Drum Sander

10-INCH DRUM SANDER For replacement parts visit Model # 65910 WENPRODUCTS.COM bit.ly/wenvideo IMPORTANT: Your new tool has been engineered and manufactured to WEN’s highest standards for dependability, ease of operation, and operator safety. When properly cared for, this product will supply you years of rugged, trouble-free performance. Pay close attention to the rules for safe operation, warnings, and cautions. If you use your tool properly and for its intended purpose, you will enjoy years of safe, reliable service. NEED HELP? CONTACT US! Have product questions? Need technical support? Please feel free to contact us at: 800-232-1195 (M-F 8AM-5PM CST) [email protected] WENPRODUCTS.COM NOTICE: Please refer to wenproducts.com for the most up-to-date instruction manual. TABLE OF CONTENTS Technical Data 2 Safety Introduction 3 General Safety Rules 4 Electrical Information 6 Specific Rules for Drum Sanders 7 Know Your Drum Sander 8 Unpacking 9 Assembly 10 Preparation 14 Operation 18 Adjustments 19 Maintenance 22 Troubleshooting 24 Exploded View and Parts List 26 Warranty Statement 30 TECHNICAL DATA Model Number: 65910 Motor: 120V, 60Hz, 10.5A Drum Speed: 1440 RPM Sandpaper Speed: 2300 FPM Conveyor Feed Speed: 0 to 10 FPM Maximum Workpiece Width: 9-1/2 in. (240mm) Minimum Workpiece Width: 3/4 in. (19mm) Maximum Workpiece Height: 3 in. (75mm) Minimum Workpiece Height: 1/4 in. (6mm) Minimum Workpiece Length 4-3/4 in. (120mm) Sandpaper Width: 3 in. Sandpaper Length: 62-1/2 in. Sanding Drum Size: 5-1/8 x 10 in. (132 x 255mm) Dust Port Diameter: 3.9 in. -

Panama’S Illegal Rosewood Logging Boom from Dalbergia Retusa

Global Ecology and Conservation 23 (2020) e01098 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Panama’s illegal rosewood logging boom from Dalbergia retusa * Ella Vardeman a, b, d, , Julie Velasquez Runk a, c a University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30602, USA b City University of New York, Graduate Center, 365 5th Ave, New York, NY, 10016, USA c Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panama d The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG), Institute of Economic Botany, 2900 Southern Boulevard, Bronx, NY 10458, USA article info abstract Article history: Over the last decade, illegal rosewood logging has surged worldwide, with much attrib- Received 9 December 2019 utable to an uptick in Chinese demand. For the last seventy-five years, Panama’s main use Received in revised form 30 April 2020 of cocobolo rosewood (Dalbergia retusa) was in small pieces for artisanal carvings, its state Accepted 30 April 2020 of conservation favoring merchantable timber for recent exploitation with the surging market. Panama’s cocobolo rosewood boom was from 2011 to 2015 and, given regulations, Keywords: was largely illicit. However, no data on cocobolo logging have been made public. Here, we Dalbergia retusa assess Panama’s cocobolo logging. We used a media analysis of Panamanian and inter- Panama Media analysis national reports on cocobolo logging from January 2000 to February 2018 coupled with Illegal logging long-term socio-environmental research to show how logging changed during the boom. We conducted a content analysis of articles to address four specific objectives: 1) to assess how cocobolo logging intensity changed over time; 2) to determine what topics related to logging were important for the press to relay to the public; 3) to show how logging changed geographically as the boom progressed; 4) to demonstrate how Panama and the international community responded to the global boom with new policies on rosewood governance. -

Phytelephas Aequatorialis in PALM BEACH COUNTY

GROWING Phytelephas aequatorialis IN PALM BEACH COUNTY Submitted by Charlie Beck Phytelephas aequatorialis is a large, solidary, pinnate palm. Its leaflets may be regularly arranged in a single plain, or they can be grouped and arranged in several planes. This is the tallest of the six Phytelephas species, it can grow 45’ tall but often tops out at 10’. This height refers to palms growing in its tropical, native habitat. In Palm Beach County it is a slow growing palm so don’t expect rapid vertical growth. In habitat fronds can measure up to 30’ long, even though stems only grow to one foot in diameter. Native habitat ranges from wet, coastal plain to 5000’ elevation on the western Andes slope in Columbia, Ecuador and Peru. Most often, P. aequatorialis is found in large stands along river banks. Seed is often dispersed by flood water. The common name for this palm is the Ecuadorean Ivory Palm. Its seed is white and very hard. P. aequatorialis is the source of vegetable ivory in Ecuador. Artisans carve figurines from this vegetable ivory. Buttons are also made from this seed. Being a dioecious palm only female plants produce vegetable ivory. Back in the 1990’s, the past president of our Society, Dale Holton, imported vegetable ivory carvings directly from Ecuador. Dale established a relationship with the exporter and eventually obtained some habitat collected seed for growing at Holton Nursery. Some of us palm enthusiasts were lucky to purchase this relatively rare palm from Dale. It was unknown if this tropical palm would grow in Palm Beach County. -

A Review of Animal-Mediated Seed Dispersal of Palms

Selbyana 11: 6-21 A REVIEW OF ANIMAL-MEDIATED SEED DISPERSAL OF PALMS SCOTT ZoNA Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, 1500 North College Avenue, Claremont, California 91711 ANDREW HENDERSON New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York 10458 ABSTRACT. Zoochory is a common mode of dispersal in the Arecaceae (palmae), although little is known about how dispersal has influenced the distributions of most palms. A survey of the literature reveals that many kinds of animals feed on palm fruits and disperse palm seeds. These animals include birds, bats, non-flying mammals, reptiles, insects, and fish. Many morphological features of palm infructescences and fruits (e.g., size, accessibility, bony endocarp) have an influence on the animals which exploit palms, although the nature of this influence is poorly understood. Both obligate and opportunistic frugivores are capable of dispersing seeds. There is little evidence for obligate plant-animaI mutualisms in palm seed dispersal ecology. In spite of a considerable body ofliterature on interactions, an overview is presented here ofthe seed dispersal (Guppy, 1906; Ridley, 1930; van diverse assemblages of animals which feed on der Pijl, 1982), the specifics ofzoochory (animal palm fruits along with a brief examination of the mediated seed dispersal) in regard to the palm role fruit and/or infructescence morphology may family have been largely ignored (Uhl & Drans play in dispersal and subsequent distributions. field, 1987). Only Beccari (1877) addressed palm seed dispersal specifically; he concluded that few METHODS animals eat palm fruits although the fruits appear adapted to seed dispersal by animals. Dransfield Data for fruit consumption and seed dispersal (198lb) has concluded that palms, in general, were taken from personal observations and the have a low dispersal ability, while Janzen and literature, much of it not primarily concerned Martin (1982) have considered some palms to with palm seed dispersal. -

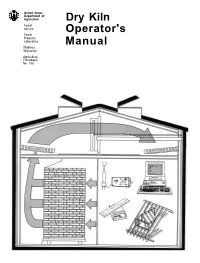

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples.