Panama’S Illegal Rosewood Logging Boom from Dalbergia Retusa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana Rosewood Case Study

MARCH, 2014 SITUATION OF GLOBAL ROSEWOOD PRODUCTION & TRADE – GHANA ROSEWOOD CASE STUDY PRESENTED BY HENRY COLEMAN - DIRECTOR OF OPERATIONS, TIMBER INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT DIVISION, FORESTRY COMMISSION Presentation Outline • INTRODUCTION • ROSEWOOD OCCURRENCE IN GHANA • HARVESTING REGULATIONS • PRODUCTION AND TRADE • ROSEWOOD MANUFACTURING (UTILIZATION) • TIMBER (ROSEWOOD) EXPORT PROCEDURES • ROSEWOOD EXPORT BAN • CHALLENGES IN ROSEWOOD PRODUCTION & TRADE IN GHANA • WAY FORWARD • CONCLUSION INTRODUCTION (I) • In Ghana Rosewood (known locally as Krayie/Kpatro) is a common name for timber exploited from the species Pterocarpus erinaceus. • The Chinese buyers/traders in Ghana also call it Kosso. INTRODUCTION (II) • The species belongs to the family Fabaceae – Papilionoideae. • Pterocarpus erinaceus is a medium- sized, generally deciduous tree 12-15 m tall, bole often of poor form. INTRODUCTION (III) • The bark surface is finely scaly fissured, brown- blackish with thin inner bark. It produces red sap when cut. INTRODUCTION (IV) • Traditionally, the species is used for the production of high quality charcoal and for building construction especially by local people. Rosewood Occurrence in Ghana (I) • The species occurs mostly in the forest savannah transitional zone and parts of the northern savannah woodland ecological zone. • Found in open forest and wooded savannah. Rosewood Occurrence in Ghana (II) • There are ten regions in Ghana. • Rosewood occurs in six of these regions, namely, Asha nti, Brong Ahafo, Northern, Upp er East, Upper West and Volta regions. HARVESTING REGULATIONS • Generally, Timber resource allocation & harvesting is based on Timber Resources Management Act, Act 547 of 1998 and the related Regulation LI 1649 of 1999. • For Rosewood, the issuance of permit to contractors prior to exploitation and monitoring exploitation once the permit has been issued have been the main regulatory mechanism since the surge in its export. -

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID

Project Rapid-Field Identification of Dalbergia Woods and Rosewood Oil by NIRS Technology –NIRS ID. The project has been financed by the CITES Secretariat with funds from the European Union Consulting objectives: TO SELECT INTERNATIONAL OR NATIONAL XYLARIUM OR WOOD COLLECTIONS REGISTERED AT THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF WOOD ANATOMISTS – IAWA THAT HAVE A SIGNIFICANT NUMBER OF SPECIES AND SPECIMENS OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA TO BE ANALYZED BY NIRS TECHNOLOGY. Consultant: VERA TERESINHA RAUBER CORADIN Dra English translation: ADRIANA COSTA Dra Affiliations: - Forest Products Laboratory, Brazilian Forest Service (LPF-SFB) - Laboratory of Automation, Chemometrics and Environmental Chemistry, University of Brasília (AQQUA – UnB) - Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC-DF MAY, 2020 Brasília – Brazil 1 Project number: S1-32QTL-000018 Host Country: Brazilian Government Executive agency: Forest Technology and Geoprocessing Foundation - FUNTEC Project coordinator: Dra. Tereza C. M. Pastore Project start: September 2019 Project duration: 24 months 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 05 2. THE SPECIES OF THE GENUS DALBERGIA 05 3. MATERIAL AND METHODS 3.1 NIRS METHODOLOGY AND SPECTRA COLLECTION 07 3.2 CRITERIA FOR SELECTING XYLARIA TO BE VISITED TO OBTAIN SPECTRAS 07 3 3 TERMINOLOGY 08 4. RESULTS 4.1 CONTACTED XYLARIA FOR COLLECTION SURVEY 10 4.1.1 BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 10 4.1.2 INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 11 4.2 SELECTED XYLARIA 11 4.3 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 13 4.4 RESULTS OF THE SURVEY OF DALBERGIA SAMPLES IN THE INTERNATIONAL XYLARIA 14 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 19 6. REFERENCES 20 APPENDICES 22 APPENDIX I DALBERGIA IN BRAZILIAN XYLARIA 22 CACAO RESEARCH CENTER – CEPECw 22 EMÍLIO GOELDI MUSEUM – M. -

Cocobolo Samuel J

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Yale University Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Bulletin Series 1923 Cocobolo Samuel J. Record George A. Garratt Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_bulletin Part of the Forest Biology Commons, Forest Management Commons, and the Wood Science and Pulp, Paper Technology Commons Recommended Citation Record, Samuel J., and George A. Garratt. 1923. ocC obolo. Yale School of Forestry Bulletin 8. 42 pp. + plates This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin Series by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Note to Readers 2012 This volume is part of a Bulletin Series inaugurated by the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in 1912. The Series contains important original scholarly and applied work by the School’s faculty, graduate students, alumni, and distinguished collaborators, and covers a broad range of topics. Bulletins 1-97 were published as bound print-only documents between 1912 and 1994. Starting with Bulletin 98 in 1995, the School began publishing volumes digitally and expanded them into a Publication Series that includes working papers, books, and reports as well as Bulletins. -

Rosewood) to CITES Appendix II.2 the New Listings Entered Into Force on January 2, 2017

Original language: English CoP18 Inf. 50 (English only / únicamente en inglés / seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Eighteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Geneva (Switzerland), 17-28 August 2019 IMPLEMENTING CITES ROSEWOOD SPECIES LISTINGS: A DIAGNOSTIC GUIDE FOR ROSEWOOD RANGE STATES This document has been submitted by the United States of America at the request of the World Resources Institute in relation to agenda item 74.* * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP18 Inf. 50 – p. 1 Draft for Comment August 2019 Implementing CITES Rosewood Species Listings A Diagnostic Guide for Rosewood Range States Charles Victor Barber Karen Winfield DRAFT August 2019 Corresponding Author: Charles Barber [email protected] Draft for Comment August 2019 INTRODUCTION The 17th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP-17) to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), held in South Africa during September- October 2016, marked a turning point in CITES’ treatment of timber species. While a number of tree species had been brought under CITES regulation over the previous decades1, COP-17 saw a marked expansion of CITES timber species listings. The Parties at COP-17 listed the entire Dalbergia genus (some 250 species, including many of the most prized rosewoods), Pterocarpus erinaceous (kosso, a highly-exploited rosewood species from West Africa) and three Guibourtia species (bubinga, another African rosewood) to CITES Appendix II.2 The new listings entered into force on January 2, 2017. -

Stay Sharp B Ill Carroll

r 72 gt a hadl o kif akig ad stay sharp y ill carroll Knife making has become a popular endeavor for woodworkers of all skill levels. This beginner’s guide will get you started. { no. 59 } rom cutting and marking in the Fshop, to hunting and camping, to preparing a simple meal, a good knife is indispensable. Mass-produced knives gt a hadl o kif akig ad can be found for every budget and use. But custom knives, which are often far more attractive, tend to get expensive very quickly. stay sharp Of course, the ultimate custom 1 2 knife would include a hand-forged and hand-sharpened blade. If you’re not up for the expense and dirty work of such an endeavor, you can still experience the pride of a well-crafted and functional addition to your tool collection. All you need is a knife kit. It’s all in there 3 4 A knife kit consists of a prefabricated blade and pins, which allows the maker to select handle materials, assemble Select wood for your scales and the knife, and shape and polish it to determine which sides will face away perfection. It requires minimal tools, from the handle portion of the knife good attention to aesthetic detail and blank, or the “tang.” Using the blank, a few hours of shop time. Once you’ve trace the shape of the tang onto each gained some knife-making experience, scale (Fig. 3). Make sure to trace the there are hundreds of types of knives tang in the proper orientation to keep (and swords, and spears) available as the best woodgrain on the visible 5 kits from a number of sources. -

10-Inch Drum Sander

10-INCH DRUM SANDER For replacement parts visit Model # 65910 WENPRODUCTS.COM bit.ly/wenvideo IMPORTANT: Your new tool has been engineered and manufactured to WEN’s highest standards for dependability, ease of operation, and operator safety. When properly cared for, this product will supply you years of rugged, trouble-free performance. Pay close attention to the rules for safe operation, warnings, and cautions. If you use your tool properly and for its intended purpose, you will enjoy years of safe, reliable service. NEED HELP? CONTACT US! Have product questions? Need technical support? Please feel free to contact us at: 800-232-1195 (M-F 8AM-5PM CST) [email protected] WENPRODUCTS.COM NOTICE: Please refer to wenproducts.com for the most up-to-date instruction manual. TABLE OF CONTENTS Technical Data 2 Safety Introduction 3 General Safety Rules 4 Electrical Information 6 Specific Rules for Drum Sanders 7 Know Your Drum Sander 8 Unpacking 9 Assembly 10 Preparation 14 Operation 18 Adjustments 19 Maintenance 22 Troubleshooting 24 Exploded View and Parts List 26 Warranty Statement 30 TECHNICAL DATA Model Number: 65910 Motor: 120V, 60Hz, 10.5A Drum Speed: 1440 RPM Sandpaper Speed: 2300 FPM Conveyor Feed Speed: 0 to 10 FPM Maximum Workpiece Width: 9-1/2 in. (240mm) Minimum Workpiece Width: 3/4 in. (19mm) Maximum Workpiece Height: 3 in. (75mm) Minimum Workpiece Height: 1/4 in. (6mm) Minimum Workpiece Length 4-3/4 in. (120mm) Sandpaper Width: 3 in. Sandpaper Length: 62-1/2 in. Sanding Drum Size: 5-1/8 x 10 in. (132 x 255mm) Dust Port Diameter: 3.9 in. -

Overview Guitar Models

14.04.2011 HOHNER - HISTORICAL GUITAR MODELS page 1 [54] Image Category Model Name Year from-to Description former retail price Musima Resonata classical; beginners guitar; mahogany back and sides Acoustic 129 (730) ca. 1988 140 DM (1990) with celluloid binding; 19 frets Acoustic A EAGLE 2004 Top Wood: Spruce - Finish : Natural - Guitar Hardware: Grover Tuners BR CLASSIC CITY Acoustic 1999 Fingerboard: Rosewood - Pickup Configuration: H-H (BATON ROUGE) electro-acoustic; solid spruce top; striped ebony back and sides; maple w/ abalone binding; mahogany neck; solid ebony fingerboard and Acoustic CE 800 E 2007 bridge; Gold Grover 3-in-line tuners; shadow P7 pickup, 3-band EQ; single cutaway; colour: natural electro-acoustic; solid spruce top; striped ebony back and sides; maple Acoustic CE 800 S 2007 w/ abalone binding; mahogany neck; solid ebony fingerboard and bridge; Gold Grover 3-in-line tuners; single cutaway; colour: natural dreadnought western guitar; Gruhn design; 20 nickel silver frets; rosewood veneer on headstock; mahogany back and sides; spruce top, Acoustic D 1 ca. 1991 950 DM (1992) scalloped bracings; mahogany neck with rosewood fingerboard; satin finish; Gotoh die-cast machine heads dreadnought western guitar; Gruhn design; rosewood back and sides; spruce top, scalloped bracings; mahogany neck with rosewood Acoustic D 2 ca. 1991 1100 DM (1992) fingerboard; 20 nickel silver frets; rosewood veneer on headstock; satin finish; Gotoh die-cast machine heads Top Wood: Sitka Spruce - Back: Rosewood - Sides: Rosewood - Guitar Acoustic -

Malagasy Precious Hardwoods Scientific and Technical Assessment to Meet CITES Objectives

Malagasy Precious Hardwoods Scientific and technical assessment to meet CITES objectives World Resources Institute 8 July 2016 Photo credit: Annah Peterson Agenda • Introduction on precious hardwoods: Rosewood and Ebony • Summary of the history and CITES Action Plan • Objectives of this assessment • Results • Recommendations • Conclusions • Discussion Back to School: Botany 101 Coconut Palm, Cocos nucifera How do you know? Leaves Habitat Fruits Trunk Coconut Palm, Cocos nucifera Which photo is Cocos nucifera? A) B) C) D) Cocos nucifera Vetchia arecina Ravenala madagascariensis Washingtonia robusta Photos: Catalogues des plantes vasculaires de Madagascar, TROPICOS Which photo is Dalbergia? A) B) C) D) Tectona grandis Dalbergia emirnensis Canarium madagascariensis Tambourissa sp. indet. Photos: Catalogues des plantes vasculaires de Madagascar, TROPICOS Malagasy Precious Woods Rosewood and Pallisander (Dalbergia spp.) Ebony (Diospyros spp.) Photos: The Guardian, Dec 23, 2013; An Introduction To Wood Species, Part 9: Ebony, Sept 11, 2013 Dalbergia and Diospyros Brazilian rosewoord, Dalbergia nigra Persimmon (kaki), Diospyros kaki Photos: Globaltrees.org; Global Survey of ex-situ ebony collections, BGCI Dalbergia and Diospyros Source: Discover Life, Global Mapper Brief History Precious Woods Industry in Madagascar • 1900’s: First documentation of the export of Malagasy rosewood • 1975: Law prohibiting the export of rosewood logs • 1991: Madagascar National Environmental Action Plan • 2000 and 2006: A moratorium on the export of rosewood and -

ROUTES of EXTINCTION: the Corruption and Violence Destroying Siamese Rosewood in the Mekong CONTENTS

ROUTES OF EXTINCTION: The corruption and violence destroying Siamese rosewood in the Mekong CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 2 THE ILLEGAL SIAMESE ROSEWOOD TRADE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 A DIRTY BLOODY BUSINESS This document has been produced with the financial assistance of UKaid, the European Union and the 7 GOVERNANCE FAILURES Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD). 9 INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION EFFORTS 10 REGIONAL HONGMU CRIME SCENES This report was written and edited by the Environmental Investigation Agency UK Ltd, 12 THE SIAMESE ROSEWOOD TRAIL and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the positions of Ukaid, the European Union, or NORAD. 22 THE IRRATIONAL EXPANSION OF THE HONGMU INDUSTRY Designed by: www.designsolutions.me.uk 24 RECOMMENDATIONS Many thanks to Emmerson Press for the printing of this report: Emmerson Press: +44 (0) 1926 854400 Printed on recycled paper May 2014 GLOSSARY OF TERMS: Siamese rosewood: refers to Dalbergia cochinchinensis Pierre spp., also known as Thailand rosewood Burmese rosewood: refers to Dalbergia bariensis spp (synonymous with Dalbergia oliveri) ENVIRONMENTAL INVESTIGATION AGENCY (EIA) Padauk: refers only to Pterocarpus macrocarpus 62/63 Upper Street, London N1 0NY, UK (synonymous with Pterocarpus pedatus) Tel: +44 (0) 20 7354 7960 Hongmu: refers to wood species or furniture made Email: [email protected] with wood species approved as official Hongmu in www.eia-international.org China’s 2000 National Standard for Hongmu Tonne/s: refers to a metric tonne, equaling 1,000 kilograms FRONT COVER: Rosewood carving in Dong Ky, Vietnam, October 2013. © EIA INTRODUCTION This is a tragic true story of high culture, peerless art forms, and a rich historical identity being warped by greed and obsession, which consumes its very foundations to extinction and sparks a violent crime wave across Asian forests. -

Wood & Veneer Care and Maintenance

Materials Wood & Veneer Care and Maintenance Wood and veneer products are natural wood, requiring more attention than other surfaces. When properly cared for, it will last long and keep looking beautiful. To maintain the quality of your Herman Miller products, please follow the cleaning procedures outlined here. Wood & Veneer Stains Herman Miller products finished with wood, wood veneer, Herman Miller woods and veneers meet strict testing standards or recut wood veneer, except the oiled Eames Lounge and for resistance to wear, light, stains, water, and pressure. Ottoman with Rosewood, Oiled Walnut, or Oiled Santos Palisander veneer, and the Eames Sofa back panels with To reduce the risk of damage, take some precautions: Oiled Walnut, unless specifically noted. Use coasters for glasses and mugs. Routine Care If a glass top is added to the wood or veneer surface, be sure it Normal Cleaning rests on felt pads. Dust regularly with a slightly damp, soft, lint-free cloth. Don’t place a potted plant on a wood or veneer surface unless Wipe dry with a dry, soft cloth in the direction of the wood grain. it’s in a water-tight container or in a drip tray. Spills should be immediately wiped up with a damp cloth. Don’t let vinyl binders stay on a surface for very long. Use protective pads under equipment with “rubber” cushioning Once a month feet. Some chemical compounds used in the feet on office Clean the surface with a soft cloth dampened with a quality equipment, such as printers and monitor stands, may leave cleaner formulated for wood furniture. -

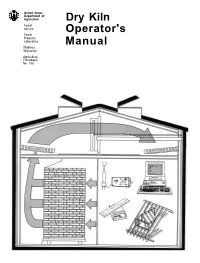

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples. -

Martin Guitar: Navigating Sustainability and Legacy

A Better World, Through Better Business Martin Guitar: Navigating Sustainability and Legacy Written by: Tristan Davis Hakan Stanis Zineb Touzani Ananya Vidyarthi Supervised and Edited by: Chet Van Wert, Senior Research Scholar, NYU Stern CSB November 2020 Introduction1 On a clear winter morning in January 2020, Jacqueline Renner, President of C.F. Martin & Co., Inc. (Martin Guitar), was reviewing the company’s strategy for sourcing environmentally sustainable wood for its acoustic guitar production operations. The two members of Renner’s staff most directly concerned with wood sustainability – Frank Untermyer, Director of Supply Chain Management, and Cindy McAllister, Director of Intellectual Property, Community and Government Relations – were discussing a crucial choice the company faced, but did not agree on the strategy Martin should adopt. Renner understood and appreciated both points of view, but could only choose one. Martin produced acoustic guitars with a uniquely rich sound, which had been preferred by popular music icons for 100 years or more. In his memoir, Chronicles, Bob Dylan described the experience of playing the Martin Dreadnought, saying that a “six-string guitar became a crystal magic wand.”i Martin’s distinctive sound resulted from a combination of innovative design and the use of “tonewoods” – specifically, rosewood, mahogany, ebony, and spruce. In the early decades of the 21st century, the company’s dependence on these raw materials had become increasingly problematic. The beauty of tonewoods meant they were in high demand by several industries, notably furniture and musical instrument manufacturing. Old-growth tonewood forests around the world were being decimated, threatening Martin’s future supply and, not incidentally, accelerating climate change.