Human Rights Violations in Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Boundaries II

Beyond Boundaries II Beyond Boundaries II Pakistan - Afghanistan Track 1.5 and II cc Connecting People Building Peace Promoting Cooperation 1 Beyond Boundaries II Beyond Boundaries II Pakistan – Afghanistan Track 1.5 and II Connecting People Building Peace Promoting Cooperation 2 Beyond Boundaries II Beyond Boundaries II ©Center for Research and Security Studies 2018 All rights reserved This publication can be ordered from CRSS Islamabad office. All CRSS publications are also available free of cost for digital download from the CRSS website. 14-M, Ali Plaza, 2nd Floor, F-8 Markaz, Islamabad, Pakistan. Tel: +92-51-8314801-03 Fax: +92-51-8314804 www.crss.pk 3 Beyond Boundaries II TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. ACRONYMS ..................................................................................................... 5 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................... 9 3. CONTEXTUALIZING BEYOND BOUNDARIES................................................... 11 4. FIRST MEETING OF THE PAKISTAN AFGHANISTAN JOINT COMMITTEE ........ 56 5. SECOND MEETING OF PAKISTAN AFGHANISTAN JOINT COMMITTEE .......... 72 6. THIRD MEETING OF PAKISTAN AFGHANISTAN JOINT COMMITTEE .............. 95 7. FOURTH MEETING OF PAKISTAN AFGHANISTAN JOINT COMMITTEE ........ 126 8. FIFTH MEETING OF PAKISTAN AFGHANISTAN JOINT COMMITTEE ON BUSINESS/TRADE ........................................................................................ 149 9. SIXTH MEETING OF PAKISTAN AFGHANISTAN JOINT COMMITTEE ............ 170 10. UNIVERSITY -

Public Sector Development Program

2011-12 Public Sector Development Program Planning and Development Department Government of Balochistan Government of Balochistan Planning & Development Department Public Sector Development Programme 2011-12 (Original) June, 2011 PREFACE The PSDP 2010 – 11 has seen its completion in a satisfactory manner. Out of 961 schemes, 405 schemes have successfully been completed at an aggregated expenditure of Rs. Rs.10.180 billion. Resultantly, communications links will get more strengthened in addition to increase in the employment rate in the province. More specifically, 60 schemes of water sector will definitely reinforce other sectors attached to it such as livestock and forestry. The PSDP 2011-12 has a total outlay of Rs.31.35 billion having 1084 schemes. Of this Rs.31.35 billion, 47.4% has been allocated to 590 ongoing schemes. The strategy adopted in preparation of the PSDP 2011-12 focuses chiefly on infrastructural sectors. Education, health and potable safe drinking water have been paid due attention with a view to bring about positive increase in their representation in social indicators. Worth mentioning is the fact that involvement of the Elected Members of the Provincial Assembly has excessively been helpful in identification of schemes in the constituencies having followed a well thought criteria. This has ensured that no sector has remained dormant as far its development and allocation of funds is concerned. Feasibility studies will be undertaken during FY 2011-12, especially for construction of mega dams to utilize 6.00 MAF flood water, which goes unutilized each year. Besides, feasibility studies for exploration and exploitation of viable minerals in the province will also be carried out. -

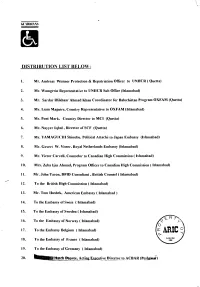

Distribution List Below

6L 1DI t\S oa DISTRIBUTION LIST BELOW: 1. Mr. Andreas Wissner Protection & Repatriation Officer to UNHCR ( Quetta) 2. Mr. Wamgerin Representative to UNIICR Sub Office (Islamabad) 3. Mr. Sardar Iftikhaar Ahmad Khan Coordinator for Balochistan Program OXFAM (Quetta) 4. Mr. Liam Maguire, Country Representative to OXFAM (Islamabad) 5. Mr. Pont Mark, Country Director to MCI (Quetta) 6. Mr. Nayyer Iqbal , Director of SCF (Quetta) 7. Mr. YAMAGUCHI Shinobu. Political Attaché to Japan Embassy (Islamabad) 8. Mr. Covert W. Visser, Royal Netherlands Embassy (Islamabad) 9. Mr. Victor Carvell, Counselor to Canadian High Commission ( Islamabad) 10. Mrs. Zeba Ijaz Ahmad, Program Officer to Canadian High Commission ( Islamabad) 11. Mr. John Tacon, DFID Consultant, British Counsel ( Islamabad) 12. To the British High Commission ( Islamabad) 13. Mr. Tom llushek, American Embassy ( Islamabad ) 14. To the Embassy of Swiss ( Islamabad) 15. To the Embassy of Sweden ( Islamabad) 16. To the Embassy of Norway ( Islamabad) 17. To the Embassy Belgium ( Islamabad) 'rteARIC EstablrsAea 18. To the Embassy of France ( Islamabad) 1999 19. To the Embassy of Germany ( Islamabad) 20, IMISSEWAtek tree, Acting Eugutive Director to ACBAR (PesNt s1-) 21. Mr. Peter Coleridge, Chief Technical Advisor to CDAP ( Peshawar) 22. To the Secretary of SA FRON ( Islamabad) 23. Mr. A. Rahman Nasir, Commissioner for Afghan Refugees ( Quetta) 24. Chief for Afghan Commissioner ( Islamabad) 25. Mr. John Green, Director to Rehabilitation Center ( OTTAWA- CANADA ) 26. Mr. Chris Kay, Head of Program Section to UNOCHA ( Islamabad) 27. Mr. Erick Demule Residence Coordinator to UNDP ( Islamabad) 28. To the Embassy of Denmark ( Islamabad) 29. Mr. Muzafar Ali Changezi, Chair man to Milo Sheed Trust (Quetta) 30. -

Newsreport October - December 2017

Registration No. L8071 VOLUME 43 NUMBER 4 NESPAK NEWSREPORT OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2017 Kachhi Canal Project put into operation ....page 3 Corporate News 02 Activities Abroad 10 - 12 Project News 03 - 09 Staff News 13 - 15 02 CORPORATE NEWS STOP PRESS Minister visits NESPAK House, Lahore Dr. Tahir M. Hayat to look after NESPAK Sardar Awais Leghari, Federal Minister of Power Division with as Managing Director NESPAK Officials Dr. Tahir Mahmood Hayat, Vice President/Head, Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering Division, has been assigned to look after the work of MD NESPAK with effect from January 03, 2018, according to the notification issued by the Power Division, Ministry of Energy. Meeting in progress NESPAK, CGGC sign MoU 146th Board of Directors meeting Dr. Tahir M. Hayat, Vice President/Head held Geotechnical & Geoenvironmental The 146th meeting of the Board of Engineering (GT&GE) Directors (BoD) of NESPAK was held on Division NESPAK, signed October 20, 2017 at the main conference a memorandum of room of NESPAK House, Lahore. The understanding (MoU) with meeting was chaired by Mr. Yousaf Mr. Zhang Zhanfeng, Naseem Khokhar, Chairman BoD NESPAK/ Authorised Chief Secretary Ministry of Energy, Islamabad. Representative of China Gezhouba Group Dr. Aamer Ahmed, Managing Director International Engineering NESPAK/Additional Secretary, Ministry of Co., Ltd. (CGGC) in Energy, Power Division, Mr. Ghanzanfar Pakistan, at a ceremony Abbas Jilani, Additional Secretary, Ministry held on November 15, Dr. Tahir M. Hayat (L) and Mr. Zhang Zhanfeng ( R) after signing the MoU of Finance, Mr. Muhammad Irfan Akram, 2017 at NESPAK House Ex-Vice President, Customer Care Mobilink Lahore. -

Pakistan: Country Report the Situa�On in Pakistan

Asylum Research Centre Pakistan: Country Report /shutterstock.com The situa�on in Pakistan Lukasz Stefanski June 2015 (COI up to 20 February 2015) Cover photo © 20 February 2015 (published June 2015) Pakistan Country Report Explanatory Note Sources and databases consulted List of Acronyms CONTENTS 1. Background Information 1.1. Status of tribal areas 1.1.1. Map of Pakistan 1.1.2. Status in law of the FATA and governance arrangements under the Pakistani Constitution 1.1.3. Status in law of the PATA and governance arrangements under the Pakistani Constitution 1.2. General overview of ethnic and linguistic groups 1.3. Overview of the present government structures 1.3.1. Government structures and political system 1.3.2. Overview of main political parties 1.3.3. The judicial system, including the use of tribal justice mechanisms and the application of Islamic law 1.3.4. Characteristics of the government and state institutions 1.3.4.1. Corruption 1.3.4.2. Professionalism of civil service 1.3.5. Role of the military in governance 1.4. Overview of current socio-economic issues 1.4.1. Rising food prices and food security 1.4.2. Petrol crisis and electricity shortages 1.4.3. Unemployment 2. Main Political Developments (since June 2013) 2.1. Current political landscape 2.2. Overview of major political developments since June 2013, including: 2.2.1. May 2013: General elections 2.2.2. August-December 2014: Opposition protests organised by Pakistan Tekreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) 2.2.3. Former Prime Minister Raja Pervaiz Ashraf 2.3. -

Pakistan News Digest June (1-15) 2016

PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST JUNE (1-15) 2016 A Select Summary of News, Views and Trends from the Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr Ashish Shukla & Dr Yaqoob-ul-Hassan (Pak-Digest, IDSA) INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES 1-Development Enclave, Near USI Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 Pakistan News Digest, JUNE (1-15) 2016 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST, JUNE (1-15) 2016 CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................. 0 ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................ 2 EDITOR’S NOTE .................................................................................................. 3 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS .......................................................................... 7 NATIONAL POLITICS ................................................................................... 7 THE PANAMA PAPERS ................................................................................ 7 PROVINCIAL POLITICS ................................................................................ 9 EDITORIALS AND OPINIONS ..................................................................... 9 FOREIGN POLICY ...............................................................................................10 EDITORIALS AND OPINION ..................................................................... 15 MILITARY AFFAIRS ...........................................................................................18 EDITORIALS -

Balochistan Review” ISSN: 1810-2174 Publication Of: Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan

- I - vISSN: 1810-2174 Balochistan Review Volume XL No. 1, 2019 Recognized by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan Editor: Abdul Qadir Mengal BALOCHISTAN STUDY CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA-PAKISTAN - II - Bi-Annual Research Journal “Balochistan Review” ISSN: 1810-2174 Publication of: Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. @ Balochistan Study Centre 2019-1 Subscription rate in Pakistan: Institutions: Rs. 300/- Individuals: Rs. 200/- For the other countries: Institutions: US$ 15 Individuals: US$ 12 For further information please Contact: Abdul Qadir Mengal Assistant Professor & Editor Balochistan Review Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Tel: (92) (081) 9211255 Facsimile: (92) (081) 9211255 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.uob.edu.pk/journals/bsc.htm No responsibility for the views expressed by authors and reviewers in Balochistan Review is assumed by the Editor, Assistant Editor, and the Publisher. - III - Editorial Board Patron in Chief: Prof. Dr. Javeid Iqbal Vice Chancellor, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Patron Prof. Dr. Abdul Haleem Sadiq Director, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Editor Abdul Qadir Mengal Asstt Professor, International Realation Department, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Assistant Editor Dr. Waheed Razzaq Assistant Professor, Brahui Department, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Members: Prof. Dr. Andriano V. Rossi Vice Chancellor & Head Dept of Asian Studies, Institute of Oriental Studies, Naples, Italy. Prof. Dr. Saad Abudeyha Chairman, Dept. of Political Science, University of Jordon, Amman, Jordon. Prof. Dr. Bertrand Bellon Professor of Int’l, Industrial Organization & Technology Policy, University de Paris Sud, France. Dr. Carina Jahani Inst. of Iranian & African Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Khan Director, Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. -

PIDE COVID-19 Newsletter E-Book

i Newsletter Team Dr. Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro Dr. Saud Ahmed Khan Dr. Hassan Rasool Dr. Amena Urooj Dr. Ashan Ul Haq Satti Fahd Zulfiqar Fizzah Khalid Butt Design Team Muhammad Siddiq Qureshi Fizzah Khalid Butt ii Foreword Since its inception in 1957, the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) has been leading development policy research and debate in the country. Liberalization, protection, socioeconomic data collection and analysis, agriculture, and tax and policy are among areas that PIDE has either innovated or contributed. Quite responsibly, the PIDE went on a war footing to understand the impact of the outbreak, when COVID-19 pandemic hit us. We daily prepared research-based Bulletins, Blogs and Newsletters and updated a Dashboard for informing audiences at every level with analysis, ideas, news and statistics. We also created an online forum that met daily, bringing in a broad set of experts, business community and members of the civil society to understand the Corona crisis and develop an action plan in the light of the evolving situation. Many among us have been making video interviews on the Corona situation for digging up more useful information on what we at PIDE are referring to as the Corona War. The videos can be viewed at the PIDE’s YouTube channel. I am proud of the PIDE researchers who rose to the task and conducted research daily to keep us abreast on the many dimensions of the crisis. This eBook collects the newsletters we prepared during the first 6 weeks of the crisis. It gives a day by day breakdown of the events during the COVID-19 outbreak as it was happening. -

2018 Winter Commencement Program

Honoring the Class of 2018 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Winter Commencement December 16, 2018 | Crisler Center Honoring the Class of 2018 WINTER COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN December 16, 2018 2:00 p.m. Candidates for graduate degrees are recommended jointly by the Executive Board of the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies and the faculty of the school or college awarding the degree. Following the School of Graduate Studies, schools are listed in order of their founding. Candidates within those schools are listed by degree then by specialization, if applicable. Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies .....................................................................................................23 College of Literature, Science, and the Arts ..............................................................................................................29 Medical School .........................................................................................................................................................33 Law School ..............................................................................................................................................................34 School of Dentistry ..................................................................................................................................................34 College of Pharmacy ................................................................................................................................................35 -

2019 Annual Report

Flint Institute of Arts ANNUAL REPORT 2018–2019 Contents president’s & executive director’s report 4 exhibitions 5–6 films 7–8 videos 9 acquisitions 10–17 loans 18–21 publications 22 development 23–24 art school 25–26 education 27 special events & facility rentals 28–30 auxiliary groups 31–32 contributions 33–36 membership 37–45 financial statement 46–48 board, staff, & faculty 49 1120 E. Kearsley St. Flint, MI 48503 810.234.1695 phone 810.234.1692 fax www.flintarts.org cover image Joan Bankemper American, born 1959 Pimlico, 2018 Manufactured and cast porcelain 1 41 /2 × 37 x 10 inches Museum purchase with funds from the Collection Endowment, 2018.56 3 ANNUAL REPORT 18–19 ANNUAL REPORT 18–19 4 President’s & Executive Director’s Report About the Flint Institute of Arts ith expansions, renovations, and construction in gallery exhibitions, all together drawing 50,900 visitors to the our rearview mirror, we began fiscal year 2018–19 galleries. Incorporated in 1928, the FIA is a privately supported, non-profit Wwith every segment of the FIA fully operational. This year, the Friends of Modern Art volunteers, by all organization. It is one of Michigan’s most significant cultural and After rebounding from the second half of 2018, and ending accounts, presented one of the best Flint Art Fairs in years. educational resources, serving people of all ages and interests. the year in the black, we are extremely grateful to our many They continued to sponsor the ever-popular film series; The Institute is supported entirely through memberships, sales, donors for their financial support. -

Citizens' Campaigns for Women's Participation in Local Government Elections 2001 and 2005

Citizens’ Campaigns for Women’s Participation in Local Government Elections 2001 and 2005 Backdrop, Glimpses of the Campaigns, Overall Results Aurat Publication and Information Service Foundation Contents The Beginning of the End............................................................................... v Acknowledgements......................................................................................... x Balochistan.............................................................................................................. 1 Awaran................................................................................................................ 3 Barkhan............................................................................................................... 7 Bolan................................................................................................................. 11 Chagai/Noshki................................................................................................... 14 Dera Bugti......................................................................................................... 22 Gwadar.............................................................................................................. 25 Jaffarabad.......................................................................................................... 29 Jhal Magsi ......................................................................................................... 34 Kalat................................................................................................................. -

Diplomatic & Consular List

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND TRADE BRUNEI DARUSSALAM DIPLOMATIC & CONSULAR LIST 2013 The Diplomatic and Consular List 2013 is published January 2013 by MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND TRADE Jalan Subok Bandar Seri Begawan BD2710 Brunei Darussalam Telephone : (673) 2261177 / 1291 / 1292 / 1293 / 1294 / 1295 Fax : (673) 2261740 (Protocol & Consular Affairs Department) Email : [email protected] Website : www.mofat.gov.bn All information is correct as of December 2012. It is requested that ammendments be reported to the Protocol and Consular Affairs Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Brunei Darussalam to have the publication updated and as correct as possible. Printed by The Government Printing Department Prime Minister’s Office Brunei Darussalam TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS Pages PART I DIPLOMATIC MISSIONS Afghanistan ...................................................................................................................... 1 Algeria .............................................................................................................................. 2 Angola .............................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina .......................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ........................................................................................................................... 5 Austria .............................................................................................................................