Structural Violence and the Industrial Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

~ Coal Mining in Canada: a Historical and Comparative Overview

~ Coal Mining in Canada: A Historical and Comparative Overview Delphin A. Muise Robert G. McIntosh Transformation Series Collection Transformation "Transformation," an occasional paper series pub- La collection Transformation, publication en st~~rie du lished by the Collection and Research Branch of the Musee national des sciences et de la technologic parais- National Museum of Science and Technology, is intended sant irregulierement, a pour but de faire connaitre, le to make current research available as quickly and inex- plus vite possible et au moindre cout, les recherches en pensively as possible. The series presents original cours dans certains secteurs. Elle prend la forme de research on science and technology history and issues monographies ou de recueils de courtes etudes accep- in Canada through refereed monographs or collections tes par un comite d'experts et s'alignant sur le thenne cen- of shorter studies, consistent with the Corporate frame- tral de la Societe, v La transformation du CanadaLo . Elle work, "The Transformation of Canada," and curatorial presente les travaux de recherche originaux en histoire subject priorities in agricultural and forestry, communi- des sciences et de la technologic au Canada et, ques- cations and space, transportation, industry, physical tions connexes realises en fonction des priorites de la sciences and energy. Division de la conservation, dans les secteurs de: l'agri- The Transformation series provides access to research culture et des forets, des communications et de 1'cspace, undertaken by staff curators and researchers for develop- des transports, de 1'industrie, des sciences physiques ment of collections, exhibits and programs. Submissions et de 1'energie . -

August 98/Lo

HSA Bulletin August 1998 contents: A human component to consider in your emergency management plans: the critical incident stress factor ................................................................... 3 A message from J. Davitt McAteer, Asst. Secretary for MSHA ............................. 9 MSHA automates enforcement with laptop computers ......................................... 10 Coal fatal accident summary ............................................................................ 11 A LOOK BACK: Anthracite coal mines and mining............................................ 12 Komatsu, Liebherr, Unit-Rig, Eculid, and Vista create a safety video for electric drive haul trucks used in surface mines.................................... 20 Metal/Nonmetal fatal accident summary .......................................................... 21 First annual Kentucky Mine Safety Conference held in eastern Kentucky........ 22 Fatality summary through June 30................................................................... 23 Southern regional mine rescue contest .............................................................. 24 FIRST AID: Heat exhaustion; Heat stroke ....................................................... 25 Texas-based BCI is helping miners develop bat-friendly ‘hangouts’ ................ 25 Utah protects bats in old mines ....................................................................... 25 The Holmes Safety Association Bulletin contains safety articles on a variety of subjects: fatal accident abstracts, studies, posters, -

Mine Site Cleanup for Brownfields Redevelopment

Mine Site Cleanup for Brownfields Redevelopment: A Three-Part Primer Solid Waste and EPA 542-R-05-030 Emergency Response November 2005 (5102G) www.brownfieldstsc.org www.epa.gov/brownfields Mine Site Cleanup for Brownfields Redevelopment: A Three-Part Primer U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response Brownfields and Land Revitalization Technology Support Center Washington, DC 20460 BROWNFIELDS TECHNOLOGY PRIMER: MINE SITE CLEANUP FOR BROWNFIELDS REDEVELOPMENT ____________________________________________________________________________________ Notice and Disclaimer Preparation of this document has been funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under Contract No. 68-W-02-034. The document was subjected to the Agency’s administrative and expert review and was approved for publication as an EPA document. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This document can be downloaded from EPA’s Brownfields and Land Revitalization Technology Support Center at http://www.brownfieldstsc.org. A limited number of hard copies of this document are available free of charge by mail from EPA’s National Service Center for Environmental Publications at the following address (please allow 4 to 6 weeks for delivery): EPA/National Service Center for Environmental Publications P.O. Box 42419 Cincinnati, OH 45242 Phone: 513-489-8190 or 1-800-490-9198 Fax: 513-489-8695 For further information about this document, please contact Mike Adam of EPA’s Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation at 703-603-9915 or by e-mail at [email protected]. The color photos on the cover illustrate the transformation possible when mine sites are cleaned up and redeveloped. -

UMWA Districts 1, 7, and 9 of Eastern Pennsylvania’S Anthracite Coal Fields)

Special Collections and University Archives Manuscript Group 109 United Mine Workers of America District 25 (Formally UMWA Districts 1, 7, and 9 of Eastern Pennsylvania’s Anthracite Coal Fields) For Scholarly Use Only Last Modified December 20, 2018 Indiana University of Pennsylvania 302 Stapleton Library Indiana, PA 15705-1096 Voice: (724) 357-3039 Fax: (724) 357-4891 Manuscript Group 109 2 United Mine Workers of America, District 25 Collection, Manuscript Group 109 Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Special Collections and University Archives 32.5 linear feet Table of Contents Historical Note, page 2 Series Descriptions, page 4 Container List, page 6-27 Historical Note Breaker Boys playing football in front of Kingston No. 4 Breaker in 1900 (Wick, 2011, p. 65). Anthracite coal, or hard coal, was first discovered and used by Native Americans and settlers in Northeastern Pennsylvania (Wyoming Valley) in the late 1790s. The anthracite coal fields are separated into three regions: the Wyoming field in the North surrounding Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, the Lehigh field surrounding the city of Hazleton, and the Schuylkill where Pottsville is located. The coal industry in these fields started slowly due few coal markets and poor transportation routes. But on February 11, 1808, Luzerne County Judge Jesse Fell successfully demonstrated the use of burning anthracite coal for domestic purposes at his tavern in Wilkes-Barre. Manuscript Group 109 3 Gradually, however, anthracite coal gained a market for use as a home-heating source due to its high efficiency and clean burning qualities. Also, with the building of canals and improved water ways, transporting anthracite coal to markets in Philadelphia and New York City became cheaper. -

Heidi and Paul Jarecki NEWPORT Township COMMUNITY NEWS

NEWPORT TOWNSHIP community NEWS Glen Lyon Condors special edition Fall 2019 Online at www.newporttownship.com Number 58 Newsletter of the Newport Township Community Organization Editors: Heidi and Paul Jarecki "Every strike brings me closer to the next home run." ~ Babe Ruth The apartment grounds on Old Newport Street, Sheatown on a fall morning Thompson's Tree Service for the removal of trees on Township Newport Township Public Business property that are thought to be a danger to adjacent properties. By John Jarecki ~ The following are items of Township business Township Manager Peter Wanchisen included the following items discussed or acted upon at meetings of the Township Commissioners in in his report: July, August, and September of 2019. 1) As of July 1, the Township sold 1,668 refuse stickers. There July 1, 2019. Township residents' comments included a mention that on were 41 home owners who had not paid and whose names were the last Fourth of July people had set off fireworks in St. Mary's Ceme- referred to the Magistrate's Office for collection. This is a delin- tery in Wanamie that were noisy and a fire hazard to homes near the quency rate of 2.2%. Cemetery. The Commissioners assured the resident that, if he calls the 2) The Commissioners voted to give a tax abatement for the Police and they have no more pressing business at the time, they will property at 161-162 Brown Row in Wanamie. The building will be respond to his call. Note: In order to call the Newport Township Police, demolished. -

Death of the Huber Breaker: Loss of an Iconic Anthracite Feature Bode J

Death of the Huber Breaker: Loss of an iconic Anthracite feature Bode J. Morin Abstract: The Huber Breaker was one of the last and largest Anthracite coal breakers in North East Pennsylvania (USA). Built in 1939, its function was to wash, break, size, and distribute coal from several linked collieries. It operated until 1976. The Huber was one of the most sophisticated of what had been hundreds of similar structures developed over the preceding century to process the region’s particular type of hard coal. An iconic structure, it did not last to see the fall of 2014 when the Huber and its accompanying support structures were demolished for their scrap value. While sitting idle for nearly 40 years, several attempts were made to stabilize and preserve the site as a museum and monument to the hundreds of thousands of people who worked in and around the coal mines. Despite hopes, community support, and a strong local preservation organization, the breaker could not be saved. Many factors affected the final fate of the site including a poor regional economy mired in a decades-long deindustrialization process, the challenges of bankruptcy proceedings for two of the companies that would come to own the site, the challenges of attempting to preserve such a large and complex structure with high liability, and social and cultural factors stemming from poor economic conditions and broad distrust of corporate and state organizations. While many industrial sites are lost following their useful period, many others are saved either as monuments or with a new function all the while serving as a physical reminder of the recent history of the region. -

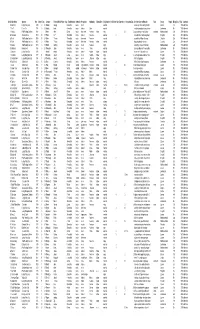

Card# Mine Name Operator Year Month Day Surname First And

Card# Mine Name Operator Year Month Day Surname First and Middle Name Age Fatal/Nonfatal In/Outside Occupation Nationality Citizen/Alien Single/Married #Children Mine Experience Occupation Exp. Accident Cause or Remarks Fault County Page# Mining Dist. Film# Anthracite 26 Dorrance Lehigh Valley Coal 1940 9 24 Rabatine George 62 nonfatal inside miner married bruised leg fall coal drililng chamber Luzerne 11th 3591 Anthracite 13 No.1 Pittson Co. 1934 3 26 Rabbitz Frank 43 nonfatal inside laborer Slavic married car door sprung back & caught finger Lackawanna 5th 3591 Anthracite 1 Alaska Phila Reading Coal Iron 1942 2 3 Raber Albert 55 fatal inside timberman American citizen single 30 5 squeezed between car & timber accidental Northumberland 23rd 3592 Anthracite 44 Hammond Hammond Coal 1939 10 19 Raber Ira F 35 nonfatal inside laborer American married 2 bruised foot fall roof dressing down Schuylkill 21st 3591 Anthracite 69 Potts Phila Reading Coal Iron 1940 10 23 Raber Thomas 73 nonfatal inside timberman American married sprained back lifting collar slope Columbia 23rd 3591 Anthracite 11 Potts Phila Reading Coal Iron 1933 2 13 Rabert Thomas 66 nonfatal inside timberman American citizen married flying chip struck him in eye Columbia 22nd 3591 Anthracite 13 Alaska Phila Reading Coal Iron 1939 5 16 Rabick Anthony 51 nonfatal inside miner American single broke finger struck with hammer Northumberland 23rd 3591 Anthracite 40 Olyphant Hudson Coal 1936 5 21 Rabrowski Julian 38 nonfatal inside miner Polish married struck by rolling coal from pile -

Nanticoke, Pennsylvania: Impacts of the Anthracite Coal Industry: a Case Study

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-22-2006 Nanticoke, Pennsylvania: Impacts of the Anthracite Coal Industry: A Case Study Amber Elias University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Elias, Amber, "Nanticoke, Pennsylvania: Impacts of the Anthracite Coal Industry: A Case Study" (2006). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 333. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/333 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NANTICOKE, PENNSYLVANIA IMPACTS OF THE ANTHRACITE COAL INDUSTRY: A CASE STUDY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree for Master of Science in Urban Studies by Amber Elias B.S. Business Millersville University, 2004 B.A. Anthropology Millersville University, 2004 M.S. Urban Studies University of New Orleans, 2006 May 2006 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Joint Urban Studies Center, the Osterhout Library, and the Nanticoke Historical Society for all their help and assistance during my research. -

Surnames Beginning With

Card# Mine Name Operator Year Month Day Surname First and Middle Name Age Fata./Nonfatal In/Outside Occupation Nationality Citizen/Alien Single/Married #Children Mine Experience Occupation Exp. Accident Cause or Remarks Fault County Page# Mining Dist. Film# 48 Archbald Glen Alden Coal 1927 10 21 Kabeski Frank 20 nonfatal inside laborer Polish alien single fall coal topping off car gangway Lackawanna 414 5th 3589 52 Truesdale 1915 12 3 Kabillie Mike 63 fatal inside doorboy Lithuanian citizen married 4 killed by cars on gangway unavoidable 122 10th 6028 86 Jeddo No.4 Jeddo Highland Coal 1927 12 28 Kabley Foster 20 nonfatal outside laborer American citizen single rail piece broke off & struck him Luzerne 535 15th 3589 84 Loree Hudson Coal 1930 11 7 Kablonski Frank 20 nonfatal inside laborer Polish citizen single struck by falling collar pillar work Luzerne 105 12th 3590 14 Gravity Slope Hudson Coal 1927 4 8 Kacar John 20 nonfatal inside runner Polish single caught by derailed car spragging Lackawanna 376 2nd 3589 7 Loree No.5 Hudson Coal 1930 5 6 Kach Benjamin 33 fatal inside miner American citizen married 4 17 10 fall coal drilling hole in coal gangway accidental Luzerne 100 12th 3590 57 Dickson 1915 7 7 Kacha Michael 38 nonfatal inside laborer Lithuanian alien fall of roof unavoidable 90 2nd 6028 10 Stanton No.7 Lehigh WilkesBarre Coal 1928 2 13 Kachanski William 37 nonfatal inside miner Polish married caught between deraied car & gob Luzerne 123 11th 3589 42 Greenwood Lehigh Navigation Coal 1931 7 7 Kachilla Joseph 19 nonfatal outside -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Social Order of the Anthracite Region, 1825-1902 HE place of the Pennsylvania anthracite region in American history has been fixed for nearly a century. The Molly TMaguire conspiracy, the miners' strikes of the i87o's and 1902, the Lattimer massacre, a railroad president who believed him- self one of "the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given control of the property interests of the country/1 and, looming behind all these, the anthracite coal trust have become stock types of nineteenth-century capitalistic oppression and labor re- sistance. A region of company towns and stores, child labor and mine disasters, starvation wages and squalor, race wars between successive waves of immigrants; they are all familiar enough. From the perspective of the mid-twentieth century, however, things that were not present in the society of the anthracite region appear no less significant than things that were. Instead of a simple melodrama of ruthless bosses and embattled workingmen, the story is one of groups, classes, institutions, and individuals so equivocally related as to be mutually unintelligible and quite heedless of each other. The region had plenty of groups, classes, institutions, and notable personages, to be sure, but it is hard to find among them 261 262 ROWLAND BERTHOFF July any functional design of reciprocal rights and duties, the nuts and bolts which pin together a stable social order. Geology was partly to blame. The anthracite region is an irregular area or discontinuous series of areas broken by mountain ridges and coalless farming valleys, altogether some four hundred square miles scattered over eight counties, reaching from a wide southern base north of the Blue Mountain, between the Susquehanna and Lehigh rivers, nearly a hundred miles northeastward along the broad Wyoming and narrow Lackawanna valleys. -

Korean Anthracite Coal Cleaning by Means of Dry and Wet Based Separation Technologies

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Mining Engineering Mining Engineering 2015 KOREAN ANTHRACITE COAL CLEANING BY MEANS OF DRY AND WET BASED SEPARATION TECHNOLOGIES Majid Mahmoodabadi University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Mahmoodabadi, Majid, "KOREAN ANTHRACITE COAL CLEANING BY MEANS OF DRY AND WET BASED SEPARATION TECHNOLOGIES" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Mining Engineering. 18. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/mng_etds/18 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Mining Engineering at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Mining Engineering by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Economic Development Policy in Kentucky

Selling the State Economic Development Policy in Kentucky By Timothy Collins With a Foreword by Bill Bishop Copyright © 2015 By Timothy Collins Permission to download this e-book is granted for educational and nonprofit use only. Quotations shall be made with appropriate citation that includes credit to the author and the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University. Published by the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University in cooperation with Then and Now Media, Bushnell, IL Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs Stipes Hall 518 Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 www.iira.org Then and Now Media 976 Washington Blvd. Bushnell IL, 61422 www.thenandnowmedia.com ISBN – 978-0-9977873-0-6 Cover Photos Army uniform trouser manufacture. Kane Manufacturing Company, Louisville, Kentucky (1941). Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress). http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/oem2002000967/PP/ Coal breaker, Pike County, Kentucky. Arthur Rothstein (1938). Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress). http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ fsa1997009623/PP/ Group of boys gathering tobacco on farm of Daniel Barrett, Spottsville, Ky., Star Route. Lewis W. Hine (1916). Photographs from the records of the National Child Labor Committee (Library of Congress). http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/nclc.00511/ To Shannon, friends forever, and Daniel, whose promising future is unfolding so well TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations vii Preface ix Foreword xi Acknowledgements xiii 1 Kentucky’s Economic Development Policy in Context 1 2 Multiple Crises and the Genesis of Economic Development Policy 19 3 Peripatetic Populist: Albert B.