“Once Coal Gets in the Blood…”: an Ethnography of Labour and Community in the Forest of Dean Coalfield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

~ Coal Mining in Canada: a Historical and Comparative Overview

~ Coal Mining in Canada: A Historical and Comparative Overview Delphin A. Muise Robert G. McIntosh Transformation Series Collection Transformation "Transformation," an occasional paper series pub- La collection Transformation, publication en st~~rie du lished by the Collection and Research Branch of the Musee national des sciences et de la technologic parais- National Museum of Science and Technology, is intended sant irregulierement, a pour but de faire connaitre, le to make current research available as quickly and inex- plus vite possible et au moindre cout, les recherches en pensively as possible. The series presents original cours dans certains secteurs. Elle prend la forme de research on science and technology history and issues monographies ou de recueils de courtes etudes accep- in Canada through refereed monographs or collections tes par un comite d'experts et s'alignant sur le thenne cen- of shorter studies, consistent with the Corporate frame- tral de la Societe, v La transformation du CanadaLo . Elle work, "The Transformation of Canada," and curatorial presente les travaux de recherche originaux en histoire subject priorities in agricultural and forestry, communi- des sciences et de la technologic au Canada et, ques- cations and space, transportation, industry, physical tions connexes realises en fonction des priorites de la sciences and energy. Division de la conservation, dans les secteurs de: l'agri- The Transformation series provides access to research culture et des forets, des communications et de 1'cspace, undertaken by staff curators and researchers for develop- des transports, de 1'industrie, des sciences physiques ment of collections, exhibits and programs. Submissions et de 1'energie . -

FODLHS Newsletter August 2018 for Download

FOREST OF DEAN LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY In this edition: ● Clearwell Magic! - See our review of Di Standing’s remarkable talk ● “We’re Not Telling” - Join a walk with our Victorian ancestors ● Iron Production in the Dean ● 70th Anniversary Dinner at the Speech House Editors Notes Occasionally you attend an event that is so good it resonates and stays with you for a long time. Di Standing’s remarkable talk. “A History of Underground Dean’, was one of those rare events. Set in the highly appropriate location of Clearwell Caves, Di entertained her audience with a wonderful talk and film. Cheryl Mayo’s cover photograph captures the atmosphere whilst members socialised over tea, cider and bread and cheese! As always John Powell has provided a warm, concise and expressive review of the event which you can find towards the back of this issue. What John has refrained from telling you is that those who helped set up the event down in the Caves ‘enjoyed’ the end of a bizarre Harry Potter convention, complete with a party of 70 from Germany who were appropriately dressed as Harry, or dragons, or monsters! Editor: Keith Walker Further thanks are due to John Powell for sourcing the interesting article 51 Lancaster Drive in the centre pages which features a walk taken locally in Victorian times. Lydney GL15 5SJ Many of you will have attended the 70th anniversary dinner held 01594 843310 recently at the Speech House. I was there along with my camera to NewsletterEditor capture the event. On reviewing my work the next day, I found to my @forestofdeanhistory.org.uk horror that not a single shot had been saved to memory. -

August 98/Lo

HSA Bulletin August 1998 contents: A human component to consider in your emergency management plans: the critical incident stress factor ................................................................... 3 A message from J. Davitt McAteer, Asst. Secretary for MSHA ............................. 9 MSHA automates enforcement with laptop computers ......................................... 10 Coal fatal accident summary ............................................................................ 11 A LOOK BACK: Anthracite coal mines and mining............................................ 12 Komatsu, Liebherr, Unit-Rig, Eculid, and Vista create a safety video for electric drive haul trucks used in surface mines.................................... 20 Metal/Nonmetal fatal accident summary .......................................................... 21 First annual Kentucky Mine Safety Conference held in eastern Kentucky........ 22 Fatality summary through June 30................................................................... 23 Southern regional mine rescue contest .............................................................. 24 FIRST AID: Heat exhaustion; Heat stroke ....................................................... 25 Texas-based BCI is helping miners develop bat-friendly ‘hangouts’ ................ 25 Utah protects bats in old mines ....................................................................... 25 The Holmes Safety Association Bulletin contains safety articles on a variety of subjects: fatal accident abstracts, studies, posters, -

CENTRE for ARCHAEOLOGY Centre for Archaeology Report 25/2001

S ("-1 1<. 6?r1 36325 a ~I~ 6503 ENGLISH HERITAGE Report 25/200 I Tree-Ring Analysis of Timbers from Gunns Mills, Spout Lane, Abenhall, Near Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire RE Howard, R R Laxton and C D litton CENTRE FOR ARCHAEOLOGY Centre for Archaeology Report 25/2001 Tree-Ring Analysis of Timbers from Gunns Mills, Spout Lane, Abenhall, Near Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire R E Howard, R R Laxton & C D Litton © English Heritage 2001 ISSN 1473-9224 The Centre for Archaeology Reports Series incorporates the former Ancient Monuments LaboratOlY Report Series. Copies of Ancient Monuments LaboratolY Reports will continue to be available from the Centrefor Archaeology (see back ofcover for details). Centre for Archaeology Report 25/2001 Tree-Ring Analysis of Timbers from Gunns Mills, Spout Lane, Abenhall, Near Mitcheldean, Gloucestershire RE Howard, R R Laxton & C D Litton Summary Fifteen samples from the timber portion of this blast furnace were analysed by tree-ring dating. This analysis produced a single site chronology of nine samples, the 244 rings it contains spanning the period AD 1438 - AD 1681. Interpretation of the sapwood, and the relative positions of the heartwoodlsapwood boundaries on the dated samples, suggests that the timbers represented, all from the northern half of the timber building, were felled in late AD 1681 or early AD 1682. This felling took place as part of a reconstruction programme, known to have taken place in AD 1682 3 and does not date to the cAD 1740 conversion of the building to a paper milL Keywords Dendrochronology Standing Building Authors' address University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham, NG7 2RD. -

16-20 Iiistiiribiii Sites Iif

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1979 pages 16-20 IIISTIIRIBIII SITES IIF U INDUSTRIAL IMPIIRTIINBE 1-. I (xi; IIN FIIRESTRY IIIIMMISSIIIN P I.I\NlI IN IIEMI ‘P rbgI‘-I -.- r fix/I ,.. I. STIIIIIIIIG ~ S.lIlIlTES The Devil‘: Chapel, in the Soowleu, near Bream. In the past arbitary divisions were often made between antiquities and the 'scars of industry‘. The former often enjoyed protection whilst the latter were frequently obliterated. Today no such divisions exist for the Council for British Archaeology cover a period from the Palaeolithic to modern times. The Department of the Environment afford statutary protection to sites of all ages by Listing and Scheduling. In addition there has been a large upsurge of interest in industrial and technological history by the general public. In 1977 Anne Ellison produced a report entitled IA survey of the archaeological implications of forestry in the Forest of Dean‘. This was produced under the auspices of the Committee for Rescue Archaeology in Avon, Gloucestershire and Somerset. A large section of this report was devoted to industrial history and particularly to the iron industry. Unfortunately some of the information presented is incorrect whilst the terminology is muddled in parts. Many of the sites noted are not on Commission land or even forested. This list has been drawn up by S.D.Coates and I.J.Standing at the request of G.S.I.A. following informal contact with the Commission. It should not be regarded as a definitive list for unknown sites of interest may well come to light“during forestry operations, particularly those connected with the iron industry before 1700. -

THE FOREST of DEAN GLOUCESTERSHIRE Archaeological Survey Stage 1: Desk-Based Data Collection Project Number 2727

THE FOREST OF DEAN GLOUCESTERSHIRE Archaeological Survey Stage 1: Desk-based data collection Project Number 2727 Volume 2 Appendices Jon Hoyle Gloucestershire County Council Environment Department Archaeology Service November 2008 © Archaeology Service, Gloucestershire County Council, November 2008 1 Contents Appendix A Amalgamated solid geology types 11 Appendix B Forest Enterprise historic environment management categories 13 B.i Management Categories 13 B.ii Types of monument to be assigned to each category 16 B.iii Areas where more than one management category can apply 17 Appendix C Sources systematically consulted 19 C.i Journals and periodicals and gazetteers 19 C.ii Books, documents and articles 20 C.iii Map sources 22 C.iv Sources not consulted, or not systematically searched 25 Appendix D Specifications for data collection from selected source works 29 D.i 19th Century Parish maps: 29 D.ii SMR checking by Parish 29 D.iii New data gathering by Parish 29 D.iv Types of data to be taken from Parish maps 29 D.v 1608 map of the western part of the Forest of Dean: Source Works 1 & 2919 35 D.vi Other early maps sources 35 D.vii The Victoria History of the County of Gloucester: Source Works 3710 and 894 36 D.viii Listed buildings information: 40 D.ix NMR Long Listings: Source ;Work 4249 41 D.x Coleford – The History of a West Gloucestershire Town, Hart C, 1983, Source Work 824 41 D.xi Riverine Dean, Putley J, 1999: Source Work 5944 42 D.xii Other text-based sources 42 Appendix E Specifications for checking or adding certain types of -

Promoter Organisation Name Works Reference Address 1 Address 2

Promoter Organisation Works Reference Address 1 Address 2 Works Location Works Type Traffic Management Start End Works Status Works C/W Name GLOUCESTERSHIRE CARRIAGEWAY TYPE 4 - UP TO EY102-GH1902000001769 SPOUT LANE ABENHALL Spout Lane, Abenhall MINOR GIVE & TAKE 28/01/2020 28/01/2020 PROPOSED WORKS COUNTY COUNCIL 0.5 MS CARRIAGEWAY TYPE 4 - UP TO Gigaclear KA030-CU004986 GRANGE COURT ROAD ADSETT Left hand fork by post box to By the right hand sign post STANDARD GIVE & TAKE 20/01/2020 31/01/2020 IN PROGRESS 0.5 MS CARRIAGEWAY TYPE 4 - UP TO Gigaclear KA030-CU005493 51488 ALDERLEY TO NEWMILLS FARM ALDERLEY Turning With Mount House On It to Outside Old Farm MINOR GIVE & TAKE 23/01/2020 27/01/2020 PROPOSED WORKS 0.5 MS CARRIAGEWAY TYPE 4 - UP TO Gigaclear KA030-CU005494 THE OLD RECTORY TO THE FURLONGS ALDERLEY 200m Before The Gate House to End Of The Road MINOR GIVE & TAKE 23/01/2020 27/01/2020 PROPOSED WORKS 0.5 MS PRIVATE STREET (NO DESIGN. Bristol Water AY009-2561804 WINTERSPRING LANE ALDERLEY OUTSIDE KINERWELL COTTAGE MINOR GIVE & TAKE 28/01/2020 30/01/2020 PROPOSED WORKS INFO. HELD) Thames Water Utilities LAYBY BY REAR OF EAGLE LINE, UNIT 3, ANDOVERSFORD CARRIAGEWAY TYPE 2 - 2.5 TO MU305-000031399394-001 A40 FROM ANDOVERSFORD BY PASS TO A436 ANDOVERSFORD MINOR TWO-WAY SIGNALS 25/01/2020 29/01/2020 PROPOSED WORKS Ltd INDUSTRIAL ESTATE,GLOUCESTER ROAD, ANDOVERSFORD, C 10 MS CARRIAGEWAY TYPE 4 - UP TO Gigaclear KA030-CU005381 ARLINGHAM ROAD ARLINGHAM Outside The Villa to Outside St Mary Church STANDARD MULTI-WAY SIGNALS 27/01/2020 31/01/2020 -

Around the Spire: September 2013 - 1

The Parish Magazine for Mitcheldean & Abenhall September 2013 Around Spire the Around the Spire: September 2013 - 1 Welcome to ‘Around the Spire’ Welcome to this September edition of the Parish Magazine. As you will see, the format of the magazine is changing. We would love to hear your feedback on the changes and would like to know what you’d be interested in seeing in the magazine in the future. You can speak to either Fr. David, Michael Heylings or Hugh James or by emailing us at [email protected]. Alongside the paper copies, this magazine is now also available on our website and can be emailed directly to you. Speak to us to find out how this can be done for you. Whether you are reading this on paper or on your computer, please consider passing it on to a friend so together we can share the church’s news around the community. Worship with Us St Michael and All Angels, Mitcheldean 1st Sunday of each month: 10.00 am Family Service Remaining Sundays: 10.00 am Sung Eucharist Tuesdays: 10.30 am Holy Communion (said) (Children and families are very welcome at all our services) St Michael’s, Abenhall 1st and 3rd Sundays of the month: 3.00 pm Holy Communion 2nd and 4th Sundays of the month: 3.00 pm Evensong For Saints Days and other Holy Day services, please see the porch noticeboards or view the website: www.stmichaelmitcheldean.co.uk The church is pleased to bring Holy Communion to those who are ill or housebound. -

Appendix IV Landscape Assessment

Mitcheldean Neighbourhood Development Plan 2016 - 2026 (To be read Appendix IV in conjunction Landscape with Policy E5 Character Landscape Assessment Character (LCA) Impact Policy) cl View 21 Valued and distinctive view of open landscape on the forest fringe. Castiard Valley with Shapridge in the distance, Statutory Forest to the left. Farmland and ancient hedgerows. Wildlife habitat for Lesser and Greater horsehoe bats and SSSI Risk Zone Natural Heritage and Landscape 6.4.11 A Landscape Character Assessment located throughout the landscape. 6.4.13 Character Assessment Draft. cottages, substantial farmhouses and (LCA) for the Forest of Dean was n Numerous transportation routes follow Castiard Vale (comprising Abenhall, some bungalows. Roofs are of slate grey undertaken in 20041. The LCA explains the valleys created by streams and brooks Jubilee Road and Plump Hill) and Wigpool or brown/dark red tiles with chimneys. All what the landscape of each place is like as they weave through the ridges. dwellings have gardens either to the front and what makes one place different from n Range of species-rich grassland habitats, Abenhall lies to the south of Mitcheldean and/or to the side and back. another. It assumes that every place is heath and bog, old orchards and ancient on the road to Flaxley off the A4136. This special and distinctive and sets out to semi-natural woodlands. ancient Parish included Jubilee Road, Plump Dene Magna School (Academy Status) show just how and where these special Hill, the Wilderness and Silver Street until is situated at the top of the hill from qualities and distinctive features occur. -

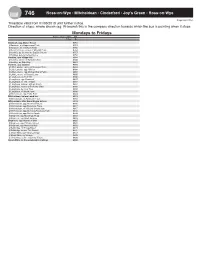

Mondays to Fridays

746 Ross-on-Wye - Mitcheldean - Cinderford - Joy’s Green - Ross-on-Wye Stagecoach West Timetable valid from 01/09/2019 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Col Notes G Boxbush, opp Manor House 0751 § Boxbush, o/s Hopeswood Park 0751 § Boxbush, nr The Rock Farm 0752 § Dursley Cross, corner of May Hill Turn 0754 § Huntley, by St John the Baptist Church 0757 § Huntley, before Newent Lane 0758 Huntley, opp Village Hall 0800 § Huntley, corner of Byfords Close 0800 § Huntley, on Oak Way 0801 Huntley, opp Sawmill 0802 § Little London, corner of Blaisdon Turn 0803 § Little London, opp Hillview 0804 § Little London, opp Orchard Bank Farm 0804 § Little London, nr Chapel Lane 0805 § Longhope, on Zion Hill 0806 § Longhope, opp Memorial 0807 § Longhope, nr The Temple 0807 § Longhope, before Latchen Room 0807 § Longhope, corner of Bathams Close 0808 § Longhope, by Yew Tree 0808 § Longhope, nr Brook Farm 0808 § Mitcheldean, opp Harts Barn 0809 Mitcheldean, before Lamb Inn 0812 § Mitcheldean, nr Abenhall House 0812 Mitcheldean, after Dene Magna School 0815 § Mitcheldean, opp Abenhall House 0816 § Mitcheldean, opp Dunstone Place 0817 § Mitcheldean, nr Mill End School stop 0817 § Mitcheldean, opp Stenders Business Park 0818 § Mitcheldean, opp Dishes Brook 0820 § Drybrook, opp Mannings Road 0823 § Drybrook, opp West Avenue 0823 Drybrook, opp Hearts of Oak 0825 § Drybrook, opp Primary School 0825 § Drybrook, opp Memorial Hall 0826 § Nailbridge, nr Bridge Road 0829 § Nailbridge, before The Branch 0832 § Steam Mills, by Primary School 0833 § Steam Mills, by Garage 0835 § Cinderford, before Industrial Estate 0836 Steam Mills, nr Gloucestershire College 0840 746 Ross-on-Wye - Mitcheldean - Cinderford - Joy’s Green - Ross-on-Wye Stagecoach West For times of the next departures from a particular stop you can use traveline-txt - by sending the SMS code to 84268. -

Mine Site Cleanup for Brownfields Redevelopment

Mine Site Cleanup for Brownfields Redevelopment: A Three-Part Primer Solid Waste and EPA 542-R-05-030 Emergency Response November 2005 (5102G) www.brownfieldstsc.org www.epa.gov/brownfields Mine Site Cleanup for Brownfields Redevelopment: A Three-Part Primer U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response Brownfields and Land Revitalization Technology Support Center Washington, DC 20460 BROWNFIELDS TECHNOLOGY PRIMER: MINE SITE CLEANUP FOR BROWNFIELDS REDEVELOPMENT ____________________________________________________________________________________ Notice and Disclaimer Preparation of this document has been funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under Contract No. 68-W-02-034. The document was subjected to the Agency’s administrative and expert review and was approved for publication as an EPA document. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This document can be downloaded from EPA’s Brownfields and Land Revitalization Technology Support Center at http://www.brownfieldstsc.org. A limited number of hard copies of this document are available free of charge by mail from EPA’s National Service Center for Environmental Publications at the following address (please allow 4 to 6 weeks for delivery): EPA/National Service Center for Environmental Publications P.O. Box 42419 Cincinnati, OH 45242 Phone: 513-489-8190 or 1-800-490-9198 Fax: 513-489-8695 For further information about this document, please contact Mike Adam of EPA’s Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation at 703-603-9915 or by e-mail at [email protected]. The color photos on the cover illustrate the transformation possible when mine sites are cleaned up and redeveloped. -

Mitcheldean Neighbourhood Development Plan 2016 - 2026

Mitcheldean Neighbourhood Development Plan 2016 - 2026 Introduction and Background Historical Development A Portrait of Mitcheldean Planning Policy Context Neighbourhood Plan Vision and Objectives Neighbourhood Plan Policies Housing Business and Employment Amenities and Community Environment Transport 1 Mitcheldean Table of Contents Maps Neighbourhood Executive Summary 3 Map 1 Mitcheldean Designated Development Plan (NDP) 1.0 Introduction and Background 5 Neighbourhood Area and Parish Area 4 2016 - 2026 2.0 Historical Development 9 Map 2 Housing Allocations 20 3.0 A Portrait of Mitcheldean 10 Map 3 Bus Depot 21 The Mitcheldean Neighbourhood 4.0 Planning Policy Context 15 Map 4 MAFF Maps Appendix VI Development Plan was made official on 5.0 Neighbourhood Plan 17 Map 5 Local Green Space Map 32 1 March 2020 following the referendum Vision and Objectives 17/18 Map 6 Mitcheldean Conservation Area 36 on 6 February 2020. 6.0 Neighbourhood Plan Policies Map 7 Views Map contained in Landscape Assessment Appendix IV 6.1 Housing 19 Map 8 Protection Zones 41 Acknowledgements 6.2 Business and Employment 27 n Kirkwells – The Planning People 6.3 Amenities and Community 30 Appendices n GRCC – Kate Baugh 6.4 Environment 36 Appendix I Listed Buildings and Non Heritage Assets n Mitcheldean Library and volunteers 6.5 Transport 43 Appendix II Environmental Records and Correspondence n Sue Henchley and Isobel Hunt Next Steps 44 Appendix III Consultations Documents n Bex Coban at Creative Bee Appendix IV Landscape Assessment and Views Document n FoDDC Appendix