Reply to RC1 on Acp-2020-461

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

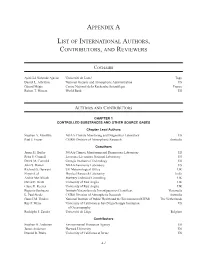

Appendix a List of International Authors, Contributors, and Reviewers

APPENDIX A LIST OF INTERNATIONAL AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, AND REVIEWERS COCHAIRS Ayité-Lô Nohende Ajavon Université de Lomé Togo Daniel L. Albritton National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration US Gérard Mégie Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique France Robert T. Watson World Bank US AUTHORS AND CONTRIBUTORS CHAPTER 1 CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES AND OTHER SOURCE GASES Chapter Lead Authors Stephen A. Montzka NOAA Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Laboratory US Paul J. Fraser CSIRO Division of Atmospheric Research Australia Coauthors James H. Butler NOAA Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Laboratory US Peter S. Connell Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory US Derek M. Cunnold Georgia Institute of Technology US John S. Daniel NOAAAeronomy Laboratory US Richard G. Derwent UK Meteorological Office UK Shyam Lal Physical Research Laboratory India Archie McCulloch Marbury Technical Consulting UK David E. Oram University of East Anglia UK Claire E. Reeves University of East Anglia UK Eugenio Sanhueza Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cientificas Venezuela L. Paul Steele CSIRO Division of Atmospheric Research Australia Guus J.M. Velders National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) The Netherlands Ray F. Weiss University of California at San Diego/Scripps Institution US of Oceanography Rodolphe J. Zander Université de Liège Belgium Contributors Stephen O. Andersen Environmental Protection Agency US James Anderson Harvard University US Donald R. Blake University of California at Irvine US A.1 AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, AND REVIEWERS Martyn P. Chipperfield University of Leeds UK Ed Dlugokencky NOAA Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Laboratory US James W. Elkins NOAA Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Laboratory US Andreas Engel Universität Frankfurt Germany David B. Harper The Queen's University of Belfast UK Emmanuel Mahieu Université de Liège Belgium Klaus Pfeilsticker Universität Heidelberg Germany Jean-Pierre Pommereau Service d'Aéronomie du CNRS France James M. -

Abstract Measurement and Analysis of Bromate Ion

ABSTRACT MEASUREMENT AND ANALYSIS OF BROMATE ION REDUCTION IN SYNTHETIC GASTRIC JUICE by Jason Dimitrius Keith Bromate ion is a possible carcinogen that is regulated by the US EPA at a Maximum Contamination Level (MCL) of 10 µg/L in drinking water. In order to propose an improved scientifically appropriate bromate ion MCL, a more rigorous scientific methodology is needed for determining low level dose health risks. The objectives of this research project were to measure bromate ion with oxidizing and/or reducing agents typically ingested in foods and drinking water. The loss of bromate ion in HCl is too slow for significant reduction in the stomach. -5 Addition of 10 M H2S, a gastric juice component, decreases the half-life from 153 to 14 minutes. The ingested reducing agents iodide ion, nitrite ion, and iron(II) decrease the lifetime of bromate ion in the stomach. Chlorine, monochloramine, and iron(III) have little actual effect on the lifetime of bromate ion. The measured rates and chemical details of the reactions are discussed. MEASUREMENT AND ANALYSIS OF BROMATE ION REDUCTION IN SYNTHETIC GASTRIC JUICE A Thesis Submitted to the faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Chemistry by Jason Dimitrius Keith Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2005 Co-Advisor________________ (Dr. Gilbert Gordon) Co-Advisor________________ (Dr. Gilbert E. Pacey) Reader_________________ (Dr. Michael W. Crowder) Reader_________________ (Dr. Hongcai Zhou) TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TABLES iii LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v INTRODUCTION 1 Bromate Ion Chemistry and Human Toxicology 1 Prior Analytical Methodology 6 Objectives 7 METHOD DEVELOPMENT AND ESTABLISHMENT OF PROTOCOLS 7 Solution Preparation 7 Preparation and Measurement of Stock HOCl/ Cl2 and ClNH2 Solutions 11 Measurement of Iron(II) and Iron(III) in Solution 12 Instrumentation. -

Standard Thermodynamic Properties of Chemical

STANDARD THERMODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF CHEMICAL SUBSTANCES ∆ ° –1 ∆ ° –1 ° –1 –1 –1 –1 Molecular fH /kJ mol fG /kJ mol S /J mol K Cp/J mol K formula Name Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Crys. Liq. Gas Ac Actinium 0.0 406.0 366.0 56.5 188.1 27.2 20.8 Ag Silver 0.0 284.9 246.0 42.6 173.0 25.4 20.8 AgBr Silver(I) bromide -100.4 -96.9 107.1 52.4 AgBrO3 Silver(I) bromate -10.5 71.3 151.9 AgCl Silver(I) chloride -127.0 -109.8 96.3 50.8 AgClO3 Silver(I) chlorate -30.3 64.5 142.0 AgClO4 Silver(I) perchlorate -31.1 AgF Silver(I) fluoride -204.6 AgF2 Silver(II) fluoride -360.0 AgI Silver(I) iodide -61.8 -66.2 115.5 56.8 AgIO3 Silver(I) iodate -171.1 -93.7 149.4 102.9 AgNO3 Silver(I) nitrate -124.4 -33.4 140.9 93.1 Ag2 Disilver 410.0 358.8 257.1 37.0 Ag2CrO4 Silver(I) chromate -731.7 -641.8 217.6 142.3 Ag2O Silver(I) oxide -31.1 -11.2 121.3 65.9 Ag2O2 Silver(II) oxide -24.3 27.6 117.0 88.0 Ag2O3 Silver(III) oxide 33.9 121.4 100.0 Ag2O4S Silver(I) sulfate -715.9 -618.4 200.4 131.4 Ag2S Silver(I) sulfide (argentite) -32.6 -40.7 144.0 76.5 Al Aluminum 0.0 330.0 289.4 28.3 164.6 24.4 21.4 AlB3H12 Aluminum borohydride -16.3 13.0 145.0 147.0 289.1 379.2 194.6 AlBr Aluminum monobromide -4.0 -42.0 239.5 35.6 AlBr3 Aluminum tribromide -527.2 -425.1 180.2 100.6 AlCl Aluminum monochloride -47.7 -74.1 228.1 35.0 AlCl2 Aluminum dichloride -331.0 AlCl3 Aluminum trichloride -704.2 -583.2 -628.8 109.3 91.1 AlF Aluminum monofluoride -258.2 -283.7 215.0 31.9 AlF3 Aluminum trifluoride -1510.4 -1204.6 -1431.1 -1188.2 66.5 277.1 75.1 62.6 AlF4Na Sodium tetrafluoroaluminate -

Electronic Structures and Spin Density Distributions of Bro2 and (HO)2Bro Radicals

Article pubs.acs.org/IC Electronic Structures and Spin Density Distributions of BrO2 and (HO)2BrO Radicals. Mechanisms for Avoidance of Hypervalency and for Spin Delocalization and Spin Polarization Rainer Glaser* and Cory Camasta Department of Chemistry, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: The results are reported of an ab initio study of bromine dioxide BrO2, 1, and of the T-shaped trans- and cis- dihydroxides 2 and 3 of dihydrogen bromate (HO)2BrO. The thermochemistry has been explored of potential synthetic routes to (HO)2BrO involving water addition to BrO2, hydroxyl addition to bromous acid HOBrO, 4, protonation/ − reduction of bromic acid HOBrO2, 5, via tautomers 6 8 of protonated bromic acid, and by reduction/protonation of − bromic acid via radical anion [HOBrO2] , 9. The potential energy surface analyses were performed at the MP2(full)/6- 311G* level (or better) and with the consideration of aqueous solvation at the SMD(MP2(full)/6-311G*) level (or better), and higher-level energies were computed at levels up to QCISD(full,T)/6-311++G(2df,2pd)//MP2. The addition of RO radical to bromous acid or bromite esters and the reduction of protonated bromic acid or protonated bromate esters are promising leads for possible synthetic exploration. Spin density distributions and molecular electrostatic potentials were computed at the QCISD(full)/6-311G*//MP2(full)/6-311G* level to characterize the electronic structures of 1−3. Both radicals employ maximally occupied (pseudo) π-systems to transfer electron density from bromine to the periphery. While the formation of the (3c-5e) π-system suffices to avoid hypervalency in 1, the π formation of the (4c-7e) -system in 2 or 3 still leaves the bromine formally hypervalent and (HO)2BrO requires delocalization of bromine density into σ*-SMOs over the trans O−Br−O moiety. -

Mechanistic and Computational Studies of Ferroin, Simple Organic Acids, and Bromine Oxides

Mechanistic and Computational Studies of Ferroin, Simple Organic Acids, and Bromine Oxides Elucidating the Complex Electrochemical Dance in an Oscillating Reaction A thesis presented to Faculty of the Graduate School of Chemistry At the University of Missouri-Columbia In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science By: Cory Camasta Dr. Rainer Glaser, Ph.D., Thesis Supervisor December 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled: MECHANISTIC AND COMPUTATIONAL STUDIES OF FERROIN, SIMPLE ORGANIC ACIDS, AND BROMINE OXIDES presented by Cory Camasta, a candidate for the Master of Science degree, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________ Dr. Rainer E. Glaser _______________________________ Dr. Thomas D. Sewell _______________________________ Dr. Aigen Li Acknowledgement The scientist’s journey is a long and challenging one. Though I do not know where mine will end, I have high hopes for it. In this short preface to the work that has directly consumed a large amount of my last nine months at the University of Missouri (and indirectly quite a bit longer), I would like to take a moment to give due thanks: Thank you to all of the dedicated researchers that allowed me to write this thesis without ever putting on a pair of protective eyewear – including the one that gave me a job. Thank you to those who loved every second of the research you did. Your sincere efforts to extend our collective knowledgebase certainly show in the fruits of your labor. Thank you to those who hated every second of the research you did. -

Chemical Names and CAS Numbers Final

Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number C3H8O 1‐propanol C4H7BrO2 2‐bromobutyric acid 80‐58‐0 GeH3COOH 2‐germaacetic acid C4H10 2‐methylpropane 75‐28‐5 C3H8O 2‐propanol 67‐63‐0 C6H10O3 4‐acetylbutyric acid 448671 C4H7BrO2 4‐bromobutyric acid 2623‐87‐2 CH3CHO acetaldehyde CH3CONH2 acetamide C8H9NO2 acetaminophen 103‐90‐2 − C2H3O2 acetate ion − CH3COO acetate ion C2H4O2 acetic acid 64‐19‐7 CH3COOH acetic acid (CH3)2CO acetone CH3COCl acetyl chloride C2H2 acetylene 74‐86‐2 HCCH acetylene C9H8O4 acetylsalicylic acid 50‐78‐2 H2C(CH)CN acrylonitrile C3H7NO2 Ala C3H7NO2 alanine 56‐41‐7 NaAlSi3O3 albite AlSb aluminium antimonide 25152‐52‐7 AlAs aluminium arsenide 22831‐42‐1 AlBO2 aluminium borate 61279‐70‐7 AlBO aluminium boron oxide 12041‐48‐4 AlBr3 aluminium bromide 7727‐15‐3 AlBr3•6H2O aluminium bromide hexahydrate 2149397 AlCl4Cs aluminium caesium tetrachloride 17992‐03‐9 AlCl3 aluminium chloride (anhydrous) 7446‐70‐0 AlCl3•6H2O aluminium chloride hexahydrate 7784‐13‐6 AlClO aluminium chloride oxide 13596‐11‐7 AlB2 aluminium diboride 12041‐50‐8 AlF2 aluminium difluoride 13569‐23‐8 AlF2O aluminium difluoride oxide 38344‐66‐0 AlB12 aluminium dodecaboride 12041‐54‐2 Al2F6 aluminium fluoride 17949‐86‐9 AlF3 aluminium fluoride 7784‐18‐1 Al(CHO2)3 aluminium formate 7360‐53‐4 1 of 75 Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number Al(OH)3 aluminium hydroxide 21645‐51‐2 Al2I6 aluminium iodide 18898‐35‐6 AlI3 aluminium iodide 7784‐23‐8 AlBr aluminium monobromide 22359‐97‐3 AlCl aluminium monochloride -

Safety Data Sheets for Each Part Listed Above Follow This Cover Sheet. Transportation Instruction

Kit Revision Date: 09 March 2020 8329TCF THERMALLY CONDUCTIVE EPOXY ADHESIVE KIT MG Chemicals Multipart Product Kit This product is a kit made up of multiple parts. Each part is an independently packaged chemical component and has independent hazard assessments. Kit Content Part Product Name Product Use A 8329TCF-A Thermally conductive epoxy resin B 8329TCF-B Thermally conductive epoxy hardener Safety Data Sheets for each part listed above follow this cover sheet. Transportation Instruction Before offering this product kit for transport, read Section 14 for all parts listed above. 8329TCF-A Thermally Conductive Epoxy Adhesive MG Chemicals UK Limited Version No: A-1.01 Issue Date:23/05/2018 Safety Data Sheet (Conforms to Regulation (EU) No 2015/830) Revision Date: 17/03/2020 L.REACH.GBR.EN SECTION 1 IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE / MIXTURE AND OF THE COMPANY / UNDERTAKING 1.1. Product Identifier Product name 8329TCF-A Synonyms SDS Code: 8329TCF-Part A; 8329TCF-6ML, 8329TCF-50ML, 8329TCF-T50ML, 8329TCF-200ML Other means of identification Thermally Conductive Epoxy Adhesive 1.2. Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Relevant identified uses Thermally conductive adhesive for bonding and thermal management Uses advised against Not Applicable 1.3. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Registered company name MG Chemicals UK Limited MG Chemicals (Head office) Heame House, 23 Bilston Street, Sedgely Dudley DY3 1JA United Address 9347 - 193 Street Surrey V4N 4E7 British Columbia Canada Kingdom Telephone +(44) 1663 362888 +(1) 800-201-8822 Fax Not Available +(1) 800-708-9888 Website Not Available www.mgchemicals.com Email [email protected] [email protected] 1.4. -

This Table Gives the Standard State Chemical Thermodynamic Properties of About 2500 Individual Substances in the Crystalline, Liquid, and Gaseous States

STANDARD THERMODYNAMIC PROPERTIES OF CHEMICAL SUBSTANCES This table gives the standard state chemical thermodynamic properties of about 2500 individual substances in the crystalline, liquid, and gaseous states. Substances are listed by molecular formula in a modified Hill order; all substances not containing carbon appear first, followed by those that contain carbon. The properties tabulated are: DfH° Standard molar enthalpy (heat) of formation at 298.15 K in kJ/mol DfG° Standard molar Gibbs energy of formation at 298.15 K in kJ/mol S° Standard molar entropy at 298.15 K in J/mol K Cp Molar heat capacity at constant pressure at 298.15 K in J/mol K The standard state pressure is 100 kPa (1 bar). The standard states are defined for different phases by: • The standard state of a pure gaseous substance is that of the substance as a (hypothetical) ideal gas at the standard state pressure. • The standard state of a pure liquid substance is that of the liquid under the standard state pressure. • The standard state of a pure crystalline substance is that of the crystalline substance under the standard state pressure. An entry of 0.0 for DfH° for an element indicates the reference state of that element. See References 1 and 2 for further information on reference states. A blank means no value is available. The data are derived from the sources listed in the references, from other papers appearing in the Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data, and from the primary research literature. We are indebted to M. V. Korobov for providing data on fullerene compounds. -

Carboline Pyroclad X1 Part A

Carboline Pyroclad X1 Part A ALTEX COATINGS LTD Chemwatch Hazard Alert Code: 3 Version No: 1.2 Issue Date: 12/04/2020 Safety Data Sheet according to HSNO Regulations Print Date: 12/04/2020 S.GHS.NZL.EN SECTION 1 IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE / MIXTURE AND OF THE COMPANY / UNDERTAKING Product Identifier Product name Carboline Pyroclad X1 Part A Synonyms Not Available Proper shipping name ENVIRONMENTALLY HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE, LIQUID, N.O.S. (contains bisphenol A/ diglycidyl ether resin, liquid) Other means of identification Not Available Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Relevant identified uses Part A of a multi-component industrial coating Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Registered company name ALTEX COATINGS LTD Address 91-111 Oropi Road, Tauranga, New Zealand Other New Zealand Telephone +64 7 5411221 Fax +64 7 5411310 Website Not Available Email [email protected] Emergency telephone number Association / Organisation NZ POISONS CENTRE CHEMWATCH EMERGENCY RESPONSE Emergency telephone 0800 764 766 +64 800 700 112 numbers Other emergency telephone Not Available +61 2 9186 1132 numbers Once connected and if the message is not in your prefered language then please dial 01 SECTION 2 HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Classification of the substance or mixture Considered a Hazardous Substance according to the criteria of the New Zealand Hazardous Substances New Organisms legislation. Classified as Dangerous Goods for transport purposes. Chronic Aquatic Hazard Category 2, Specific target organ toxicity - single exposure Category 2, Specific target organ toxicity - repeated exposure Classification [1] Category 2, Eye Irritation Category 2, Reproductive Toxicity Category 2, Skin Sensitizer Category 1, Skin Corrosion/Irritation Category 3, Acute Aquatic Hazard Category 2 Legend: 1. -

Principles of Chemical Nomenclature a GUIDE to IUPAC RECOMMENDATIONS Principles of Chemical Nomenclature a GUIDE to IUPAC RECOMMENDATIONS

Principles of Chemical Nomenclature A GUIDE TO IUPAC RECOMMENDATIONS Principles of Chemical Nomenclature A GUIDE TO IUPAC RECOMMENDATIONS G.J. LEIGH OBE TheSchool of Chemistry, Physics and Environmental Science, University of Sussex, Brighton, UK H.A. FAVRE Université de Montréal Montréal, Canada W.V. METANOMSKI Chemical Abstracts Service Columbus, Ohio, USA Edited by G.J. Leigh b Blackwell Science © 1998 by DISTRIBUTORS BlackweilScience Ltd Marston Book Services Ltd Editorial Offices: P0 Box 269 Osney Mead, Oxford 0X2 0EL Abingdon 25 John Street, London WC1N 2BL Oxon 0X14 4YN 23 Ainslie Place, Edinburgh EH3 6AJ (Orders:Tel:01235 465500 350 Main Street, Maiden Fax: MA 02 148-5018, USA 01235 465555) 54 University Street, Carlton USA Victoria 3053, Australia BlackwellScience, Inc. 10, Rue Casmir Delavigne Commerce Place 75006 Paris, France 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02 148-5018 Other Editorial Offices: (Orders:Tel:800 759 6102 Blackwell Wissenschafts-Verlag GmbH 781 388 8250 KurfUrstendamm 57 Fax:781 388 8255) 10707 Berlin, Germany Canada Blackwell Science KK Copp Clark Professional MG Kodenmacho Building 200Adelaide St West, 3rd Floor 7—10 Kodenmacho Nihombashi Toronto, Ontario M5H 1W7 Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104, Japan (Orders:Tel:416 597-1616 800 815-9417 All rights reserved. No part of Fax:416 597-1617) this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or Australia BlackwellScience Pty Ltd transmitted, in any form or by any 54 University Street means, electronic, mechanical, Carlton, Victoria 3053 photocopying, recording or otherwise, (Orders:Tel:39347 0300 except as permitted by the UK Fax:3 9347 5001) Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. -

Bromate Production in Ozone Contactors

BROMATE PRODUCTION IN OZONE CONTACTORS Richard S. Yates, Graduate Research Assistant Michael K. Stenstrom, Professor and Chairman Department of Civil Engineering University of California, Los Angeles, 90024 Abstract A pilot-scale study of the ozonation of surface waters containing moderate levels of bromide .(Br-) was conducted in order to collect kinetic parameters suitable for modeling the production of bromate. Operating in a pre- ozonation mode, the two surface waters were dosed under conditions designed to theoretically provide greater than 0.51ogto inactivation levels for Giardia. Key results from the experimental study and kinetic analysis of bromate formation in these two waters are: 1) Bromate production results from rapid free radical processes. The slower, recursive reactions involving the direct oxidation of bromide and hypobromite by ozone are insignificant. 2) Ozone residual is the controlling factor in the rate and extent of bromate formation. 3) Hypobromite and hypobromous acid are formed primarily as minor byproducts of oxybromine radical decay, and do not play a significant role as precursors at pHs less than 9.0. 4) Naturally occurring organic matter plays a complex role in production and consumption of both oxygen radicals and possibly oxybromine radicals. 5) Gas-liquid contactor hydrodynamics play a critical role in bromate formation, influencing mass transfer rates, peak ozone residuals, spatial-temporal concentration gradients, and liquid backmixing phenomena. INTRODUCTION Boomate Toxicity Oral feeding studies involving rodents have shown that the ingestion of bromate (Br03) via drinking water can promote the formation of renal tumors (Kurokawa et al., 1987). Given this data, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has classified Br03 as a possible human carcinogen, and is likely to propose a maximum contantinant level in the range of 5 - 10 ,ug/L . -

Chlorine, Bromine, Iodine

SECTION 5 Chlorine, Bromine, Iodine M. SCHMEISSER Chlorin e CI2 Commercially available liquid chlorine, which is obtained by electrolysis of alkali, is not sufficiently pure and must therefore be purified by method I. On the other hand, a gas that is already largely free of such impurities as Os and chlorine oxides is produced by the reaction of hydrated manganese dioxide with pure hydrochloric acid. For this preparation, see method II below. I. Chlorine from a steel cylinder is passed consecutively through two wash bottles or columns containing concentrated H2S04, a tube or column containing CaO (to remove any HC1 that might be present), a tube containing P2Os, and finally into a container placed in a Dry Ice-acetone bath, where it is condensed and liquefied. The liquefied Cl2 is repeatedly vaporized and condensed while noncondensable gases (02) are continuously removed with a pump. Finally, the liquid Cl2 is fractionated in high vacuum and passed into receivers cooled with liquid nitrogen. (For the appa• ratus see, for example, Part I, p. 66 ff.) Only the middle frac• tion is used for further work. II. Mn02xH20* + 4 HC1 = MnCl2 + (x + 2)H20 + Cl2 ~ 100 145.88 70.91 *x ~ 0.8 for a product of about 86% purity. Concentrated, air-free hydrochloric acid (d 1.16) is added dropwise to precipitated hydrated manganese dioxide (e.g., the 86% pure commercially obtainable material) in a flask equipped with a dropping funnel and a gas outlet tube. The gas formation may be regulated by moderate heating. The chlorine thus formed is passed through water (to remove entrained HC1) and H2S04 (carried out as in method I, that is, 272 5.