Myanmar's 2015 Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Treaty on European Union)

L 108/88EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2005 (Acts adopted under Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/340/CFSP of 25 April 2005 extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Common Position 2004/423/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (8) In the event of a substantial improvement in the overall political situation in Burma/Myanmar, the suspension of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in these restrictive measures and a gradual resumption of particular Article 15 thereof, cooperation with Burma/Myanmar will be considered, after the Council has assessed developments. Whereas: (9) Action by the Community is needed in order to (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common implement some of these measures, Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures 1 against Burma/Myanmar ( ). HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (2) On 25 October 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/730/CFSP on additional restrictive Article 1 measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP shall be Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2). replaced by Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (3) On 21 February 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/149/CFSP amending Annex II to Article 2 Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (3). Common Position 2004/423/CFSP is hereby renewed for a period of 12 months. (4) The Council would recall its position on the political situation in Burma/Myanmar and considers that recent developments do not justify suspension of the restrictive Article 3 measures. -

Direction Relating to Foreign Currency Transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) As Amended Made Under Regulation 5 of The

Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) as amended made under regulation 5 of the Banking (Foreign Exchange) Regulations 1959 This compilation was prepared on 22 October 2008 taking into account amendments up to Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma – Amendment to the Annex and Variation of Exemptions – Amendment to the Annexes (16/10/2008) Prepared by the Office of Legislative Drafting and Publishing, Attorney-General’s Department, Canberra Federal Register of Legislative Instruments F2008C00574 2 Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) The Reserve Bank of Australia, pursuant to regulation 5 of the Banking (Foreign Exchange) Regulations 1959, hereby directs that: 1. a person must not, either on the person’s own behalf or on behalf of another person, buy, borrow, sell, lend or exchange foreign currency in Australia, or otherwise deal with foreign currency in any other way in Australia; 2. a resident, or a person acting on behalf of a resident, must not buy, borrow, sell, lend or exchange foreign currency outside Australia, or otherwise deal with foreign currency in any other way outside Australia; 3. a person must not be a party to a transaction, being a transaction that takes place in whole or in part in Australia or to which a resident is a party, that has the effect of, or involves, a purchase, borrowing, sale, loan or exchange of foreign currency, or otherwise relates to foreign currency where the transaction relates to property, securities or funds owned or controlled directly or indirectly by, or otherwise relates to payments directly or indirectly to, or for the benefit of any person listed in the Annex to this direction. -

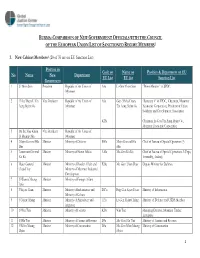

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

Actos Adoptados En Aplicación Del Título V Del Tratado De La Unión Europea

L 154/116ES Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea 21.6.2003 (Actos adoptados en aplicación del título V del Tratado de la Unión Europea) DECISIÓN 2003/461/PESC DEL CONSEJO de 20 de junio de 2003 por la que se aplica la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC sobre Birmania/Myanmar EL CONSEJO DE LA UNIÓN EUROPEA, DECIDE: Vista la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC, de 28 de abril de 2003, sobre Birmania/Myanmar (1), y en particular sus artículos Artículo 1 8 y 9, junto con el apartado 2 del artículo 23 del Tratado de la La lista de personas que figura en el anexo de la Posición Unión Europea, Común 2003/297/PESC se sustituye por la lista que figura en el anexo. Considerando lo siguiente: (1) De acuerdo con el artículo 9 de la Posición Común Artículo 2 2003/297/PESC, la ampliación de determinadas sanciones allí establecidas, así como las prohibiciones Queda levantada la suspensión de las disposiciones del apartado establecidas en el apartado 2 del artículo 2 de la misma 2 del artículo 2 de la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC tal y Posición Común se suspendieron hasta el 29 de octubre como se establece en la letra b) del artículo 9 de la Posición de 2003, salvo que el Consejo decida lo contrario. Común. (2) A la vista del persistente deterioro de la situación política Artículo 3 en Birmania, en particular el arresto de Aung San Suu Kyi y otros destacados miembros de la Liga Nacional La presente Decisión surtirá efecto a partir del día de su adop- para la Democracia y el cierre de las oficinas de la ción. -

CSIS Myanmar Trip Report

September 10, 2012 CSIS Myanmar Trip Report STATE OF THE NATION AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR U.S. POLICY Ernest Bower, Michael Green, Christopher Johnson, and Murray Hiebert SUMMARY In August 2012, a group of senior CSIS Asia specialists visited Myanmar to explore the political, economic, and social reforms launched by the new civilian government and develop policy recommendations for the U.S. government. The trip is part of a Myanmar Project launched by CSIS and funded in part by the C.V. Starr Foundation. The CSIS delegation was led by Ernest Bower, director and senior adviser, Southeast Asia Program, and included Michael Green, senior vice president and Japan Chair, Christopher Johnson, senior adviser and Freeman Chair in China Studies, and Murray Hiebert, deputy director and senior fellow, Southeast Asia Program. Eileen Pennington, deputy director of the Women’s Empowerment Program at the Asia Foundation, accompanied the group as an observer. Myanmar is in the early stages of moving toward transformational change in nearly all respects, including political and economic reform, the opening of space for civil society, empowerment of women, defining foreign policy and national security priorities, and finding a path to reconciliation with its diverse ethnic groups. However, there was evidence that significant challenges remain with respect to governance and reconciliation with ethnic minorities and that rights abuses continue in some areas, despite the overall positive direction from the leadership of the new government. Real change appears to be under way, but it is not irreversible. Myanmar’s government, opposition leaders, civil society groups, and business leaders all emphasized that there is an urgency and immediacy around the process of change in their country. -

COUNCIL DECISION 2003/907/CFSP of 22 December 2003 Implementing Common Position 2003/297/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar

24.12.2003 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 340/81 COUNCIL DECISION 2003/907/CFSP of 22 December 2003 implementing Common Position 2003/297/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: Having regard to Common Position 2003/297/CFSP of 28 Article 1 April 2003 on Burma/Myanmar (1) and in particular Article 8 thereof, in conjunction with Article 23(2) of the Treaty on The list of persons set out in the Annex to Common Position European Union, 2003/297/CFSP is hereby replaced by the list set out in the Annex. Whereas: Article 2 (1) In accordance with Article 8 of Common Position 2003/ This Decision shall take effect on the date of its adoption. 297/CFSP, the Council, acting upon a proposal by a Member State or the Commission, is to adopt modifica- Article 3 tions to the list contained in the Annex to that Common Position of persons subject to the restrictive measures as This Decision shall be published in the Official Journal of the required. European Union. (2) By Decision 2003/461/CFSP (2), the Council updated the list contained in the Annex to Common Position 2003/ Done at Brussels, 22 December 2003. 297/CFSP. For the Council (3) Because of the appointment of the new members of the Government of Burma/Myanmar on 25 August 2003, a The President further update of that list is necessary, A. COSTA (1) OJ L 106, 29.4.2003, p. 36. Common Position as amended by Deci- sion 2003/461/CFSP (OJ L 154, 21.6.2003, p. -

Rg Um Tvingun Burma, Ofl.Indd

Nr. 581 26. júní 2012 REGLUGERÐ um breytingu á reglugerð um þvingunaraðgerðir sem varða Búrma/Mýanmar, Egyptaland, Gíneu, Íran, Líbýu og Sýrland nr. 870/2011. 1. gr. Almenn ákvæði. Á eftir ii. lið a-liðar 2. gr. komi eftirfarandi: iii. reglugerð ráðsins (ESB) nr. 1083/2011 frá 27. október 2011 um breytingu á reglugerð ráðs ins (EB) nr. 194/2008 um að endurnýja og efla þvingunaraðgerðir vegna Búrma/Mýanmar, sbr. fylgiskjal 7; iv. reglugerð ráðsins (ESB) nr. 409/2012 frá 14. maí 2012 um að fresta tilteknum þvingunar aðgerðum sem mælt er fyrir um í reglugerð ráðsins (EB) nr. 194/2008 um að endurnýja og efla þvingunaragerðir vegna Búrma/Mýanmar, sbr. fylgiskjal 8. Í stað V. og VI. viðauka komi nýir viðaukar, sbr. framkvæmdarreglugerð framkvæmdastjórnar innar (ESB) nr. 891/2011, sem eru birtir í fylgiskjali 9, með eftirfarandi breytingum: (1) Í V. viðauka skal færslunni Mayar (H.K) Ltd breytt í: „Mayar India Ltd (Yangon Branch) 37, Rm (703/4), Level (7), Alanpya Pagoda Rd, La Pyayt Wun Plaza, Dagon, Yangon.“, sbr. framkvæmdarreglugerð ráðsins (ESB) nr. 1345/2011. (2) VI. viðauki breytist í samræmi við 2. gr. reglugerðar ráðsins (ESB) nr. 1083/2011 að ofan. Fylgiskjöl 7-9 við reglugerð nr. 870/2011 að ofan eru birt sem fylgiskjöl 1-3 við reglugerð þessa. 2. gr. Frestun framkvæmdar. Auk þeirrar frestunar á framkvæmd þvingunaraðgerða, sem kveðið er á um í reglugerð ráðsins nr. 409/2012 að ofan, skal fresta framkvæmd ákvæða 5. og 6. gr. um landgöngubann og þróunar aðstoð hvað Búrma/Mýanmar varðar til 30. apríl 2013, sbr. ákvörðun ráðsins 2012/225/SSUÖ frá 26. -

Release Lists ( Last Updated on 21 July 2021)

Father's Section of No Name Sex /Age Status Date of Arrest Plaintiff Released Date Address Remark Name Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Chief Minister of 1-Feb-21 and 10- Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 1 Salai Lian Luai M Chin State Chin State Feb-21 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Chin State Hluttaw Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 2 Zo Bawi M 1-Feb-21 Chin State Speaker 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Ethnic Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 3 Naing Thet Lwin M 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw Affairs 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Minister of Natural Kyi and President U Win Myint were Resources and Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 4 Ohn Win M 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw Environmental 21 ministers in the states and regions were also Conservation detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Social Released on 2 Feb detained. -

Cabinet of Myanmar Government (8Th August '14)

The Cabinet of the Myanmar Government (As of 8th August, 2014) Office of the President(大統領府) President U Thein Sein Vice President U Nyan Tun Vice President Dr. Sai Mauk Kham President Office (1) Union Minister U Thein Nyunt President Office (2) Union Minister U Soe Maung President Office (3) Union Minister U Soe Thein President Office (4) Union Minister U Aung Min President Office (5) Union Minister U Tin Naing Thein President Office (6) Union Minister U Hla Tun President Office (4) Deputy Minister U Aung Thein President Office (1) Deputy Minister U Kyaw Kyaw Win Ministry 1. Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation(農業・灌漑省) Union Minister U Myint Hlaing Deputy Minister U Ohn Than Deputy Minister U Khin Zaw 2. Ministry of Border Affairs(国境省) Union Minister Lt-Gen Thet Naing Win Deputy Minister Maj-Gen Maung Maung Ohn Deputy Minister Maj-Gen Tin Aung Chit 3.Ministry of Commerce(商業省) Union Minister Wunna Kyaw Htin U Win Myint Deputy Minister Dr. Pwint San 4.Ministry of Communications and Information Technology(通信・IT 省) Union Minister U Myat Hein Deputy Minister U Win Than Deputy Minister U Thaung Tin 5. Ministry of Construction (建設省) Union Minister U Kyaw Lwin Deputy Minister U Soe Tint Deputy Minister Dr. Win Myint 6. Ministry of Cooperatives(共同組合省) Union Minister U Kyaw Hsan Deputy Minister U Than Tun 7. Ministry of Culture(文化省) Union Minister U Aye Myint Kyu Deputy Minister Daw Sandar Khin Deputy Minister U Than Swe 8. Ministry of Defense(国防省) Union Minister Lt. Gen. Wai Lwin Deputy Minister Maj-Gen. -

2002/831/Cfsp)

23.10.2002 EN Official Journal of the European Communities L 285/7 COUNCIL COMMON POSITION of 21 October 2002 amending and extending Common Position 96/635/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar (2002/831/CFSP) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in parti- Article 1 cular Article 15 thereof, The listof persons subjecttoa visa ban and a freezing of funds contained in the Annex to Common Position 96/635/CFSP is Whereas: hereby replaced by the list in the Annex hereto. Article 2 (1) Common Position 96/635/CFSP of 28 October 1996 on Burma/Myanmar (1) expires on 29 October 2002. Common Position 96/635/CFSP is hereby extended until 29 April 2003. (2) There has been insufficient progress in the situation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar. Article 3 This Common Position shall take effect on the date of its adop- (3) Common Position 96/635/CFSP should therefore be tion. extended for a further six months. Article 4 (4) Changes in the composition of the regime in Burma/ This Common Position shall be published in the Official Myanmar require an updating of the list of persons Journal. subject to restrictive measures contained in the Annex to Common Position 96/635/CFSP first introduced by Council Common Position 2000/346/CFSP of 26 April 2000 extending and amending Common Position 96/ Done atLuxembourg, 21 October2002. 635/CFSP (2). For the Council (5) Action by the Community is needed in order to imple- The President ment some of the measures cited below, P. -

New Government in Myanmar: Profiles of Ministers

http://www.ide.go.jp July 26, 2011 Toshihiro Kudo, IDE-JETRO New Government in Myanmar: Profiles of Ministers On March 30, 2011, a new government was born in Myanmar. On this, the 18th and final day of the regular session of Parliament convened on January 31 in accordance with the 2010 general election, Prime Minister Thein Sein took office as president, with First Secretary of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) Tin Aung Myint Oo1 and Sai Mauk Kham (of the Shan, an ethnic minority) as vice presidents. All three had already been elected to their positions as president or vice president in a vote in Parliament on February 4, and on March 30 each took the following oath in accordance with the 2008 Constitution in front of Speaker Khin Aung Myint at the inauguration ceremony in Parliament. “I, (name), do solemnly and sincerely promise and declare that I will be loyal to the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the citizens and hold always in esteem non-disintegration of the Union, non-disintegration of national solidarity and perpetuation of sovereignty. I will uphold and abide by the Constitution and its Laws. I will carry out the responsibilities uprightly to the best of my ability and strive for further flourishing the eternal principles of justice, liberty and equality. I will dedicate myself to the service of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar.” (Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Article 65) Before the oath of office, Speaker Khin Aung Myint read SPDC Notification No.5/2011 (March 30, 2011) indicating that the SPDC has transferred legislative, executive, and judiciary powers to the individuals elected and approved by Parliament, and that the SPDC was thereby dissolved.