CSIS Myanmar Trip Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reform in Myanmar: One Year On

Update Briefing Asia Briefing N°136 Jakarta/Brussels, 11 April 2012 Reform in Myanmar: One Year On mar hosts the South East Asia Games in 2013 and takes I. OVERVIEW over the chairmanship of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2014. One year into the new semi-civilian government, Myanmar has implemented a wide-ranging set of reforms as it em- Reforming the economy is another major issue. While vital barks on a remarkable top-down transition from five dec- and long overdue, there is a risk that making major policy ades of authoritarian rule. In an address to the nation on 1 changes in a context of unreliable data and weak econom- March 2012 marking his first year in office, President Thein ic institutions could create unintended economic shocks. Sein made clear that the goal was to introduce “genuine Given the high levels of impoverishment and vulnerabil- democracy” and that there was still much more to be done. ity, even a relatively minor shock has the potential to have This ambitious agenda includes further democratic reform, a major impact on livelihoods. At a time when expectations healing bitter wounds of the past, rebuilding the economy are running high, and authoritarian controls on the popu- and ensuring the rule of law, as well as respecting ethnic lation have been loosened, there would be a potential for diversity and equality. The changes are real, but the chal- unrest. lenges are complex and numerous. To consolidate and build on what has been achieved and increase the likeli- A third challenge is consolidating peace in ethnic areas. -

050411.Pos Com Burma1

RELEX 11/04/2005 POSITION COMMUNE DU CONSEIL du prorogeant et modifiant les mesures restrictives à l'encontre de la Birmanie/du Myanmar LE CONSEIL DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE, vu le traité sur l'Union européenne, et notamment son article 15, considérant ce qui suit: (1) Le 26 avril 2004, le Conseil a arrêté la position commune 2004/423/PESC 1 renouvelant les mesures restrictives à l'encontre de la Birmanie/du Myanmar. (2) Le 25 octobre 2004, le Conseil a arrêté la position commune 2004/730/PESC 2 concernant des mesures restrictives supplémentaires à l'encontre de la Birmanie/du Myanmar et modifiant la position commune 2004/423/PESC. (3) Le 21 février 2005, le Conseil a arrêté la position commune 2005/149/PESC 3 modifiant l'Annexe II de la position commune 2004/423/PESC. (4) L'Union européenne rappelle sa position sur la situation politique qui règne en Birmanie/au Myanmar et considère que les développements récents ne justifient pas une suspension des mesures restrictives. (5) En conséquence, les mesures restrictives à l'encontre de la Birmanie/du Myanmar énoncées par la position commune 2004/423/PESC, telle que modifiée respectivement par les positions communes 2004/730/PESC et 2005/149/PESC, devraient rester en vigueur. (6) Le Conseil considère que, bien que certaines mesures imposées par la position commune 2004/423/PESC visent des personnes associées au régime birmanes/du Myanmar ainsi que les membres de leur famille, les enfants en-dessous de 18 ans, ne devraient, en principe, pas être ciblés. (7) Il convient d'apporter des modifications techniques aux listes annexées à la position commune 2004/423/PESC. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Treaty on European Union)

L 108/88EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2005 (Acts adopted under Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/340/CFSP of 25 April 2005 extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Common Position 2004/423/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (8) In the event of a substantial improvement in the overall political situation in Burma/Myanmar, the suspension of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in these restrictive measures and a gradual resumption of particular Article 15 thereof, cooperation with Burma/Myanmar will be considered, after the Council has assessed developments. Whereas: (9) Action by the Community is needed in order to (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common implement some of these measures, Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures 1 against Burma/Myanmar ( ). HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (2) On 25 October 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/730/CFSP on additional restrictive Article 1 measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP shall be Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2). replaced by Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (3) On 21 February 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/149/CFSP amending Annex II to Article 2 Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (3). Common Position 2004/423/CFSP is hereby renewed for a period of 12 months. (4) The Council would recall its position on the political situation in Burma/Myanmar and considers that recent developments do not justify suspension of the restrictive Article 3 measures. -

Direction Relating to Foreign Currency Transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) As Amended Made Under Regulation 5 of The

Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) as amended made under regulation 5 of the Banking (Foreign Exchange) Regulations 1959 This compilation was prepared on 22 October 2008 taking into account amendments up to Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma – Amendment to the Annex and Variation of Exemptions – Amendment to the Annexes (16/10/2008) Prepared by the Office of Legislative Drafting and Publishing, Attorney-General’s Department, Canberra Federal Register of Legislative Instruments F2008C00574 2 Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) The Reserve Bank of Australia, pursuant to regulation 5 of the Banking (Foreign Exchange) Regulations 1959, hereby directs that: 1. a person must not, either on the person’s own behalf or on behalf of another person, buy, borrow, sell, lend or exchange foreign currency in Australia, or otherwise deal with foreign currency in any other way in Australia; 2. a resident, or a person acting on behalf of a resident, must not buy, borrow, sell, lend or exchange foreign currency outside Australia, or otherwise deal with foreign currency in any other way outside Australia; 3. a person must not be a party to a transaction, being a transaction that takes place in whole or in part in Australia or to which a resident is a party, that has the effect of, or involves, a purchase, borrowing, sale, loan or exchange of foreign currency, or otherwise relates to foreign currency where the transaction relates to property, securities or funds owned or controlled directly or indirectly by, or otherwise relates to payments directly or indirectly to, or for the benefit of any person listed in the Annex to this direction. -

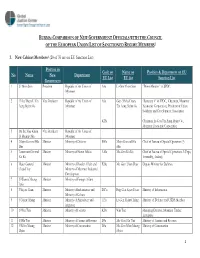

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

Actos Adoptados En Aplicación Del Título V Del Tratado De La Unión Europea

L 154/116ES Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea 21.6.2003 (Actos adoptados en aplicación del título V del Tratado de la Unión Europea) DECISIÓN 2003/461/PESC DEL CONSEJO de 20 de junio de 2003 por la que se aplica la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC sobre Birmania/Myanmar EL CONSEJO DE LA UNIÓN EUROPEA, DECIDE: Vista la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC, de 28 de abril de 2003, sobre Birmania/Myanmar (1), y en particular sus artículos Artículo 1 8 y 9, junto con el apartado 2 del artículo 23 del Tratado de la La lista de personas que figura en el anexo de la Posición Unión Europea, Común 2003/297/PESC se sustituye por la lista que figura en el anexo. Considerando lo siguiente: (1) De acuerdo con el artículo 9 de la Posición Común Artículo 2 2003/297/PESC, la ampliación de determinadas sanciones allí establecidas, así como las prohibiciones Queda levantada la suspensión de las disposiciones del apartado establecidas en el apartado 2 del artículo 2 de la misma 2 del artículo 2 de la Posición Común 2003/297/PESC tal y Posición Común se suspendieron hasta el 29 de octubre como se establece en la letra b) del artículo 9 de la Posición de 2003, salvo que el Consejo decida lo contrario. Común. (2) A la vista del persistente deterioro de la situación política Artículo 3 en Birmania, en particular el arresto de Aung San Suu Kyi y otros destacados miembros de la Liga Nacional La presente Decisión surtirá efecto a partir del día de su adop- para la Democracia y el cierre de las oficinas de la ción. -

Pyithu Hluttaw Raises Queries to Ministries, Approves Bill, Tables Motion

FIGHTING CHILD LABOUR REQUIRES COLLECTIVE EFFORT OF ALL STAKEHOLDERS PAGE-8 (OPINION) HLUTTAW NATIONAL Amyotha Hluttaw raises questions to ministries, Nay Pyi Taw Pyithu Hluttaw Speaker U T Khun Myat Council, approves bill amending 1959 Defence Services Act receives ROK Ambassador PAGE-2 PAGE-3 Vol. VII, No. 106, 12th Waxing of Second Waso 1382 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Friday, 31 July 2020 Pyithu Hluttaw raises queries to ministries, approves bill, tables motion YITHU Hluttaw organ- ized its 7th-day meeting Pof 17th regular session yesterday. MP U Khin Maung Thein from Sagaing region constitu- ency asked for new paints on the 90-year-old Sagaing bridge (Inwa). Deputy Minister for Trans- port and Communications U Kyaw Myo replied some parts of 3,948-foot-long bridge are be- ing painted, and its remaining areas could be painted on the availability of budget allocation in 2021-2022 financial year. MP U Myo Zaw Oo from Lewe constituency asked about organizational structure, re- sponsibility and accountability of third party organizations, and policies and directives for their operations. Deputy Minister for Con- struction Dr Kyaw Linn replied Pyithu Hluttaw Speaker U T Khun Myat presides over 7th-day meeting on 30 July. PHOTO: MNA that the staff members from Quality Control Division of Vil- Myothit constituency asked Kunlong constituency asked for from Yaksawk constituency Taungdwingyi constituency lage Development Department for inspection of quality con- maintenance of bank erosion at about upgrade of an inter-vil- tabled a motion that urged the are representing the govern- trol at the inter-village roads 9 places of Neint Taint creek, lage road in his constituency, Union Government to increase ment in quality control inspec- and allocation of budget for the MP U Sai Ngaung Sai Hein from MP U Thein Tun from Kyaung- traffic awareness campaign and tion; although they do not earn damaged roads. -

Politicalmonitor No.35

Euro-Burma Office 17-23 November 2012 Political Monitor 2012 POLITICAL MONITOR NO.35 OFFICIAL MEDIA U.S. PRESIDENT MAKES HISTORIC VISIT TO BURMA U.S. President Barack Obama arrived in Burma’s old capital Rangoon on 19 November and became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the Southeast Asian nation. During his visit, Obama met his Burmese counterpart President Thein Sein and the two leaders discussed the strengthening and promoting of bilateral relations as well as country’s on-going democratic reforms process. In their official talks, the Burmese leader stressed the need for closer cooperation between the two countries, to promote democracy, human rights, capacity building and in doing so, bilateral relations should be based on mutual respect and understanding. President Obama acknowledged the reform measures taking place in the country and also praised the Burmese President in addressing the issues of child soldiers and nuclear non-proliferation. The US President also met with the Speaker of the Lower House Thura Shwe Mann and leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD) Aung San Suu Kyi. One significant part of Mr Obama’s visit, was a speech given at the Convocation Hall of the University of Rangoon, which witnessed past episodes of pro-democratic student unrests, including mass demonstrations in 1988 that ended in a bloody military crackdown. In his speech Obama said that in recent decades the “two countries became strangers” and that his visit was to extend the hand of friendship. The President went on to add that no process of reform could succeed without national reconciliation and also called for an end to sectarian unrest in western Rakhine State. -

COUNCIL DECISION 2003/907/CFSP of 22 December 2003 Implementing Common Position 2003/297/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar

24.12.2003 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 340/81 COUNCIL DECISION 2003/907/CFSP of 22 December 2003 implementing Common Position 2003/297/CFSP on Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: Having regard to Common Position 2003/297/CFSP of 28 Article 1 April 2003 on Burma/Myanmar (1) and in particular Article 8 thereof, in conjunction with Article 23(2) of the Treaty on The list of persons set out in the Annex to Common Position European Union, 2003/297/CFSP is hereby replaced by the list set out in the Annex. Whereas: Article 2 (1) In accordance with Article 8 of Common Position 2003/ This Decision shall take effect on the date of its adoption. 297/CFSP, the Council, acting upon a proposal by a Member State or the Commission, is to adopt modifica- Article 3 tions to the list contained in the Annex to that Common Position of persons subject to the restrictive measures as This Decision shall be published in the Official Journal of the required. European Union. (2) By Decision 2003/461/CFSP (2), the Council updated the list contained in the Annex to Common Position 2003/ Done at Brussels, 22 December 2003. 297/CFSP. For the Council (3) Because of the appointment of the new members of the Government of Burma/Myanmar on 25 August 2003, a The President further update of that list is necessary, A. COSTA (1) OJ L 106, 29.4.2003, p. 36. Common Position as amended by Deci- sion 2003/461/CFSP (OJ L 154, 21.6.2003, p. -

Rg Um Tvingun Burma, Ofl.Indd

Nr. 581 26. júní 2012 REGLUGERÐ um breytingu á reglugerð um þvingunaraðgerðir sem varða Búrma/Mýanmar, Egyptaland, Gíneu, Íran, Líbýu og Sýrland nr. 870/2011. 1. gr. Almenn ákvæði. Á eftir ii. lið a-liðar 2. gr. komi eftirfarandi: iii. reglugerð ráðsins (ESB) nr. 1083/2011 frá 27. október 2011 um breytingu á reglugerð ráðs ins (EB) nr. 194/2008 um að endurnýja og efla þvingunaraðgerðir vegna Búrma/Mýanmar, sbr. fylgiskjal 7; iv. reglugerð ráðsins (ESB) nr. 409/2012 frá 14. maí 2012 um að fresta tilteknum þvingunar aðgerðum sem mælt er fyrir um í reglugerð ráðsins (EB) nr. 194/2008 um að endurnýja og efla þvingunaragerðir vegna Búrma/Mýanmar, sbr. fylgiskjal 8. Í stað V. og VI. viðauka komi nýir viðaukar, sbr. framkvæmdarreglugerð framkvæmdastjórnar innar (ESB) nr. 891/2011, sem eru birtir í fylgiskjali 9, með eftirfarandi breytingum: (1) Í V. viðauka skal færslunni Mayar (H.K) Ltd breytt í: „Mayar India Ltd (Yangon Branch) 37, Rm (703/4), Level (7), Alanpya Pagoda Rd, La Pyayt Wun Plaza, Dagon, Yangon.“, sbr. framkvæmdarreglugerð ráðsins (ESB) nr. 1345/2011. (2) VI. viðauki breytist í samræmi við 2. gr. reglugerðar ráðsins (ESB) nr. 1083/2011 að ofan. Fylgiskjöl 7-9 við reglugerð nr. 870/2011 að ofan eru birt sem fylgiskjöl 1-3 við reglugerð þessa. 2. gr. Frestun framkvæmdar. Auk þeirrar frestunar á framkvæmd þvingunaraðgerða, sem kveðið er á um í reglugerð ráðsins nr. 409/2012 að ofan, skal fresta framkvæmd ákvæða 5. og 6. gr. um landgöngubann og þróunar aðstoð hvað Búrma/Mýanmar varðar til 30. apríl 2013, sbr. ákvörðun ráðsins 2012/225/SSUÖ frá 26. -

Release Lists ( Last Updated on 21 July 2021)

Father's Section of No Name Sex /Age Status Date of Arrest Plaintiff Released Date Address Remark Name Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Chief Minister of 1-Feb-21 and 10- Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 1 Salai Lian Luai M Chin State Chin State Feb-21 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Chin State Hluttaw Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 2 Zo Bawi M 1-Feb-21 Chin State Speaker 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Ethnic Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 3 Naing Thet Lwin M 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw Affairs 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Minister of Natural Kyi and President U Win Myint were Resources and Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 4 Ohn Win M 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw Environmental 21 ministers in the states and regions were also Conservation detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Social Released on 2 Feb detained.