“Nga Tapuwae O Hotumauea” Maori Landmarks on Riverside Reserves Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton Gardens Waikato Museum

‘Shovel ready’ Infrastructure Projects: Project Information Form About this Project Information Form The Government is seeking to identify ‘shovel ready’ infrastructure projects from the Public and certain Private Infrastructure sector participants that have been impacted by COVID 19. Ministers have advised that they wish to understand the availability, benefits, geographical spread and scale of ‘shovel ready’ projects in New Zealand. These projects will be considered in the context of any potential Government response to support the construction industry, and to provide certainty on a pipeline of projects to be commenced or re- commenced, once the COVID 19 Response Level is suitable for construction to proceed. The Infrastructure Industry Reference Group, chaired by Mark Binns, is leading this work at the request of Ministers, and is supported by Crown Infrastructure Partners Limited (CIP). CIP is now seeking information using this Project Information Form from relevant industry participants for 1 projects/programmes that may be suitable for potential Government support. The types of projects we have been asked to consider is outlined in Mark Binns’ letter dated 25 March 2020. CIP has prepared Project Information Guidelines which outline the approach CIP will take in reviewing and categorising the project information it receives (Guidelines). Please submit one form for each project that you consider meets the criteria set out in the Guidelines. If you have previously provided this information in another format and/or as part of a previous process feel free to submit it in that format and provide cross-references in this form. Please provide this information by 5 pm on Tuesday 14 April 2020. -

Te Awamutu Courier Thursday, August 12, 2021

Rural sales specialist Howard Ashmore 027 438 8556 | rwteawamutu.co.nz Thursday, August 12, 2021 Rosetown Realty Ltd Licensed REAA2008 BRIEFLY New venue for Vax centre can do eco-waste collection The Urban Miners eco-waste collection will now run from the by-pass parking area in front of the Te Awamutu Sports club rooms on Albert Park Dr. 250 jabs per day They will continue to be held on the first Sunday of every month from 9am to 11am, recommencing September 5. Variety of topics for Continuing Ed. guest speaker Noldy Rust will be speaking about ‘variety of work’ at the Continuing Education meeting on Wednesday, August 18 from 10am. Of Swiss descent, Noldy has been a dairy farmer most of his life. He is involved in several dairy industry organisations including Vetora Waikato and the Smaller Herds Association. Recently he worked as an area manager for a maize Waipa¯iwi relations adviser Shane Te Ruki leads Waipa¯mayor Jim Mylchreest and guests into Te Awamutu’s newly opened Covid-19 community vaccination seed company and is now centre. Photo / Dean Taylor working as a Rural Real Estate agent as part of the he former Bunnings store in Welcome area So far, more than 140,000 local Ray White team. Te Awamutu has been trans- of the newly vaccinations have been administered He also enjoys being part of formed into the Waikato’s opened Covid- across the Waikato to date. It will take other local organisations, latest Covid-19 community 19 community until the end of the year to ensure including the local theatre Tvaccination centre. -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

Rangiriri to Huntly — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa

10/5/2021 Rangiriri to Huntly — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa Rangiriri to Huntly Walking Difculty Easy Length 21.4 km Journey Time 1 day Region Waikato Sub-Region North Waikato Part of Collections Te Araroa - New Zealand's Trail , Te Araroa - North Island Track maintained by Te Araroa Trail Trust https://www.walkingaccess.govt.nz/track/rangiriri-to-huntly/pdfPreview 1/4 10/5/2021 Rangiriri to Huntly — NZ Walking Access Commission Ara Hīkoi Aotearoa Once you've crossed the bridge, continue a further 150m around the rst corner and there is a stile to take you across the rst fence to this riverside track which runs parallel to Te Ōhākī Road. On a clear day, you'll see the orange-topped chimneys of the Huntly Power station standing in the distance. 1.5km in, past Maurea Marae, there's a monument to the Ngāti Naho chief, Te Wheoro, whose personal history embodies the extraordinary stresses of colonial rule on Waikato Māori as they argued strategies to preserve tribal identity. Te Wheoro sided at rst with the Crown. In 1857, he spoke against setting up a Māori king and, at the great conference of Māori leaders at Kohimarama in 1860, spoke again in favour of the Government. Governor Grey's British troops invaded Waikato territory in July 1863. In November that year, the British Troops overcame the Māori redoubt at Rangiriri, forcing the Māori King, Tāwhiao, out of Ngāruawāhia to sanctuary around Waitomo and Te Kūiti. In the years that followed, Te Wheoro acted as an intermediary for the Government's negotiation with the King. -

Attachment 4

PARK ROAD SULLIVAN ROAD DIVERS ROAD SH 1 LAW CRESCENT BIRDWOOD ROAD WASHER ROAD HOROTIU BRIDGE ROAD CLOVERFIELD LANE HOROTIU ROAD KERNOTT ROAD PATERSON ROAD GATEWAY DRIVE EVOLUTION DRIVE HE REFORD D RIVE IN NOVA TIO N W A Y MARTIN LANE BOYD ROAD HENDERSON ROAD HURRELL ROAD HUTCHINSON ROAD BERN ROAD BALLARD ROAD T NNA COU R VA SA OSBORNE ROAD RK D RIVER DOWNS PA RIVE E WILLIAMSON ROAD G D RI ONION ROAD C OU N T REYNOLDS ROAD RY L ANE T E LANDON LANE R A P A A ROAD CESS MEADOW VIEW LANE Attachment 4 C SHERWOOD DOWNS DRIVE HANCOCK ROAD KAY ROAD REDOAKS CLOSE REID ROAD RE E C SC E V E EN RI L T IV D A R GRANTHAM LANE KE D D RIVERLINKS LANE RIVERLINKS S K U I P C A E L O M C R G N E A A A H H D O LOFTUS PLACE W NORTH CITY ROAD F I ONION ROAD E LD DROWERGLEN S Pukete Farm Park T R R O SE EE T BE MCKEE STREET R RY KUPE PLACE C LIMBER HILL HIGHVIEW COURT RESCENT KESTON CRESCENT VIKING LANE CLEWER LANE NICKS WAY CUM BE TRAUZER PLACE GRAHAM ROAD OLD RUFFELL ROAD RLA KOURA DRIVE ND DELIA COURT DR IV ET ARIE LANE ARIE E E SYLVESTER ROAD TR BREE PLACE E S V TRENT LANE M RI H A D ES G H UR C B WESSEX PLACE WALTHAM PLACE S GO R IA P Pukete Farm Park T L T W E M A U N CE T I HECTOR DRIVE I A R H E R S P S M A AMARIL LANE IT IR A N M A N I N G E F U A E G ED BELLONA PLACE Y AR D M E P R S T L I O L IN Moonlight Reserve MAUI STREET A I A L G C A P S D C G A D R T E RUFFELL ROAD R L L A O E O N R A E AVALON DRIVEAVALON IS C N S R A E R E D C Y E E IS E E L C N ANN MICHELE STREET R E A NT ESCE NT T WAKEFIELD PLACE E T ET B T V TE KOWHAI ROAD KAPUNI STRE -

8 February 2012 Time: 9.30 Am Meeting Room: Committee Room 1 Venue: Municipal Building, Garden Place, Hamilton

Notice of Meeting: I hereby give notice that an ordinary meeting of Operations & Activty Performance Committee will be held on: Date: Wednesday, 8 February 2012 Time: 9.30 am Meeting Room: Committee Room 1 Venue: Municipal Building, Garden Place, Hamilton Barry Harris Chief Executive Operations & Activity Performance Committee OPEN AGENDA Membership Chairperson Cr M Gallagher Deputy Chairperson Cr A O’Leary Members Her Worship the Mayor Ms J Hardaker Cr D Bell Cr P Bos Cr G Chesterman Cr M Forsyth Cr J Gower Cr R Hennebry Cr D Macpherson Cr P Mahood Cr M Westphal Cr E Wilson Quorum: A majority of members (including vacancies) Meeting Frequency: Monthly Fleur Yates Senior Committee Advisor 1 February 2012 [email protected] Telephone: 838 6771 www.hamilton.co.nz Operations & Activity Performance Committee Agenda 8 February 2012- OPEN Page 1 of 145 Role & Scope . The overall mandate of this committee is to request and receive information concerning Councils activities and develop consistent and pragmatic reasoning that will enable Council to be informed of future directions, options and choices. The committee has no decision making powers unless for minor matters that improve operational effectiveness, efficiency or economy. To monitor key activities and services (without operational interference in the services) in order to better inform elected members and the community about key Council activities and issues that arise in the operational arm of the Council. No more than 2 operational areas to report each month . Receive reports relating to organisational performance against KPI’s, delivery of strategic goals, and community outcomes and vision. -

Potential Shallow Seismic Sources in the Hamilton Basin Project 16/717 5 July 2017

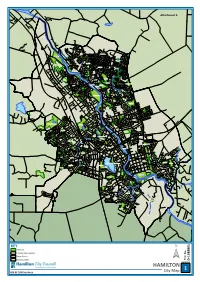

Final Report on EQC Potential shallow seismic sources in the Hamilton Basin Project 16/717 5 July 2017 Vicki Moon & Willem de Lange School of Science University of Waikato 1. Introduction Following the exposure of a fault within a cutting in a new sub-division development in NE Hamilton, an initial investigation suggested the presence of 4 fault zones within the Hamilton Basin (Figure 1) that represented a potential hazard to infrastructure within the Basin. Hence, the overall aim of the proposal put to EQC was to refine the locations of four potentially active faults within the Hamilton Basin. To achieve this aim, two main phases of geophysical surveying were planned: 1. A seismic reflection survey along the Waikato River channel; and 2. Resistivity surveying to examine the sub- surface structure of identified fault zones. Additional MSc student projects, funded by Waikato Regional Council, were proposed to map the surface geology and geomorphology, and assess the liquefaction potential within the Hamilton Basin. During the course of the project, the initial earthworks Figure 1: Map of the four fault zones that were initially identified from geomorphology for the Hamilton Section of the Waikato Expressway and surface fault exposures, as presented in provided exposures of faults, which resulted in some the original proposal. modification of the project. 2. Methods The two main methodological approaches planned for this project were: 1. A high resolution CHIRP seismic reflection survey along the Waikato River within the Hamilton Basin. A previous study examining the stability of the river banks in response to fluctuating water levels (Wood, 2006) had obtained detailed data on the morphology of the river bed using multi-beam and single-beam echo sounders (MBES and SBES respectively), and side scan sonar. -

Appendix 2 S.42A Hearings Report - Historic Heritage and Notable Trees 28 July 2020

Appendix 2 S.42a Hearings Report - Historic Heritage and Notable Trees 28 July 2020 SCHEDULE 30.1 Historic Heritage Items Delete the notified version of Schedule 30.1 and insert the following: Schedule 30.1 Historic Heritage Items1 Assessment of Historic Buildings and Structures Heritage Assessment Criteria The heritage significance and the value of the historic heritage has been assessed based on evaluation against the following heritage qualities: Archaeological Significance: • The potential of the building, structure and setting to define or expand the knowledge of earlier human occupation, activities or events • The potential for the building, structure and setting to provide evidence to address archaeological research • The building, structure and setting is registered by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga, or recorded by the New Zealand Archaeological Association Site Recording Scheme Architectural Significance • The style of the building or structure is representative of a significant development period in the Waikato District and associated with a significant activity (e.g. institutional, industrial, commercial or transportation) • The building or structure has distinctive or special attributes of an aesthetic or functional nature (e.g. materials, detailing, functional layout, landmark status or symbolic value) • The building or structure uses unique or uncommon building materials or demonstrates an innovative method of construction, or is an early example of the use of particular building technique. • The building or structure’s architect, designer, engineer or builder as a notable practitioner or made a significant contribution to Waikato District. Cultural Significance • The building, structure and setting is important as a focus of spiritual, political, national or other cultural sentiment • The building, structure and setting is a context for community identity or sense of place and provides evidence of cultural or historical continuity. -

Te Awa Lakes: Housing Economics

5 April 2018 Attn: Paul Radich Development Planner, Te Awa Lakes Development Perry Group Via email: [email protected] CC: [email protected] Te Awa Lakes: Housing Economics Dear Paul, This letter aims to provide ongoing assessment in relation to demand for Qualifying Developments, and also comments on local demand for residential housing in the proposed Te Awa Lakes Special Housing Area. Updating RCG’s Housing Commentary We summarise the key points from RCG’s Assessment of Economic Effects report for Te Awa Lakes below. 1 We have updated these points with more recent data where available: • Net migration into New Zealand remains at near-record levels of around 70,000 a year. • Auckland is still not keeping pace with its own housing shortage, i.e. ‘supply’ of new homes is not matching ‘demand’ from population growth. • Auckland is likely to keep losing people to neighbouring regions such as the Waikato, especially when there is housing pressure (as is currently the case). • Auckland’s house price boom began in 2012 and spread to Hamilton by 2015. In both cities, and most other parts of New Zealand, prices have flattened out in 2017-18. • The average house value in Hamilton is now $548,000, compared with $363,000 four years ago. 2 • Building consents in Hamilton, Waikato and Waipa remain at near-record levels, but have plateaued. 1 http://www.hamilton.govt.nz/our-council/council- publications/districtplans/ODP/Documents/Te%20Awa%20Lakes%20Private%20Plan%20Chan ge/Appendix_6_Assessment_of_Economic_Effects.PDF 2 Data from https://www.qv.co.nz/property-trends/residential-house-values , for Feb 2018 compared with Feb 2014 RCG | CONSTRUCTIVE THINKING. -

Historic Overview - Pokeno & District

WDC District Plan Review – Built Heritage Assessment Historic Overview - Pokeno & District Pokeno The fertile valley floor in the vicinity of Pokeno has most likely been occupied by Maori since the earliest days of their settlement of Aotearoa. Pokeno is geographically close to the Tamaki isthmus, the lower Waikato River and the Hauraki Plains, all areas densely occupied by Maori in pre-European times. Traditionally, iwi of Waikato have claimed ownership of the area. Prior to and following 1840, that iwi was Ngati Tamaoho, including the hapu of Te Akitai and Te Uri-a-Tapa. The town’s name derives from the Maori village of Pokino located north of the present town centre, which ceased to exist on the eve of General Cameron’s invasion of the Waikato in July 1863. In the early 1820s the area was repeatedly swept by Nga Puhi war parties under Hongi Hika, the first of several forces to move through the area during the inter-tribal wars of the 1820s and 1830s. It is likely that the hapu of Pokeno joined Ngati Tamaoho war parties that travelled north to attack Nga Puhi and other tribes.1 In 1822 Hongi Hika and a force of around 3000 warriors, many armed with muskets, made an epic journey south from the Bay of Islands into the Waikato. The journey involved the portage of large war waka across the Tamaki isthmus and between the Waiuku River and the headwaters of the Awaroa and hence into the Waikato River west of Pokeno. It is likely warriors from the Pokeno area were among Waikato people who felled large trees across the Awaroa River to slow Hika’s progress. -

To Get Your Weekend Media Kit

YOUR WEEKEND MAGAZINE LIFT-OUT 2020 MEDIA KIT & DEADLINES Special Issues & Features 2020 MATARIKI ISSUE BUY NZ MADE! WOMEN OF TECHNOLOGY FITNESS SPECIAL JULY 11 JULY 25 INFLUENCE AUGUST 8 AUGUST 30 A celebration of the Maori New Year. Focusing on a range of locally owned JULY - AUGUST (issues TBC) How to make technology work for Trends, tips and motivation as winter and operated businesses producing you (and your family) rather than the draws to a close. Stories about influential and inspiring cool innovative products. other way around. women, in the lead-up to the Women of Influence Awards. Pictured: Previous winner Jackie Clark for her work supporting victims of domestic violence. ECO-INTERIORS OUTDOOR CHRISTMAS FOOD BEST NZ-MADE GIFTS 20 TOP KIWIS OF ISSUE ENTERTAINING NOVEMBER 28 DECEMBER 5 2020 OCTOBER 3 NOVEMBER 14 Drink and food recipes and ideas for Celebrating local creativity and DECEMBER 12 the big day. innovation, a beautiful gift guide Beautiful homes at less cost to the Recipes and ideas for BBQs and Politicians, musicians, sports people, with a difference. planet. summer parties. actors, artists, everyday heroes... It's a great lineup of featuring the people who made a challenging year a little more bearable for all of us. NOTE: Please confirm your editorial special features and issues topics and/or dates may change subject to interest. Your Weekend is New Zealand’s "Packed with practical advice for home and garden, fashion inspiration, profiles of favourite weekend newspaper-insert intriguing people, and stories about social trends and big issues, Your Weekend is the magazine (Canon Media Awards 2017). -

Research Essay for Postgraduate Diploma in Arts (History) 2011

Saintly, Sinful or Secular 1814 – 1895 viewed through the lens of Te Māramataka 1895 and its historical notes Research Essay for Postgraduate Diploma in Arts (History) 2011 George Connor 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Mihi 5 Introduction 6 Chapter 1 Almanacs, Ordo, and Lectionaries 9 Chapter 2 An examination of Te Māramataka 1895, and the historical notes 21 The historical notes in Te Māramataka 1895 as a lens to look at the first 81 years of the Anglican Mission in Aotearoa 30 Chapter 3 By whom and for whom was Te Māramataka 1895 written? 42 Summary 58 Conclusions 60 Appendix 1 Te Māramataka 1895, pages 1, 3, & 15, these show the front cover, Hanuere as an example of a month, and 2 Himene on last page 62 Appendix 2 Māori evangelists in Sir Kingi Ihaka’s ‘Poi’ from A New Zealand Prayer Book ~ He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa 65 Appendix 3 Commemorations particularly associated with Aotearoa in A New Zealand Prayer Book ~ He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa 67 Appendix 4 Sample page from Te Rāwiri 1858 showing Tepara Tuarua these are for Oketopa and Nowema as examples of the readings for the daily services using the lectionary common to Anglicans from 1549 till 1871 68 Appendix 5 Sample page from the Calendar, with Table of Lessons from the Book of Common Prayer 1852 ~ this is an English version of a page similar to the table in Appendix 4, it also shows the minor saints’ days for the months from September to December 69 Appendix 6 Sample page from Te Rāwiri 1883 showing Tepara II for Oketopa and Nowema with the new 1871 readings for