Research Essay for Postgraduate Diploma in Arts (History) 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kerikeri Mission House Conservation Plan

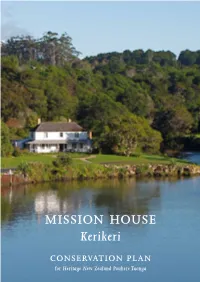

MISSION HOUSE Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN i for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Mission House Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN This Conservation Plan was formally adopted by the HNZPT Board 10 August 2017 under section 19 of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014. Report Prepared by CHRIS COCHRAN MNZM, B Arch, FNZIA CONSERVATION ARCHITECT 20 Glenbervie Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand Phone 04-472 8847 Email ccc@clear. net. nz for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Northern Regional Office Premier Buildings 2 Durham Street East AUCKLAND 1010 FINAL 28 July 2017 Deed for the sale of land to the Church Missionary Society, 1819. Hocken Collections, University of Otago, 233a Front cover photo: Kerikeri Mission House, 2009 Back cover photo, detail of James Kemp’s tool chest, held in the house, 2009. ISBN 978–1–877563–29–4 (0nline) Contents PROLOGUES iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Commission 1 1.2 Ownership and Heritage Status 1 1.3 Acknowledgements 2 2.0 HISTORY 3 2.1 History of the Mission House 3 2.2 The Mission House 23 2.3 Chronology 33 2.4 Sources 37 3.0 DESCRIPTION 42 3.1 The Site 42 3.2 Description of the House Today 43 4.0 SIGNIFICANCE 46 4.1 Statement of Significance 46 4.2 Inventory 49 5.0 INFLUENCES ON CONSERVATION 93 5.1 Heritage New Zealand’s Objectives 93 5.2 Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 93 5.3 Resource Management Act 95 5.4 World Heritage Site 97 5.5 Building Act 98 5.6 Appropriate Standards 102 6.0 POLICIES 104 6.1 Background 104 6.2 Policies 107 6.3 Building Implications of the Policies 112 APPENDIX I 113 Icomos New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value APPENDIX II 121 Measured Drawings Prologue The Kerikeri Mission Station, nestled within an ancestral landscape of Ngāpuhi, is the remnant of an invitation by Hongi Hika to Samuel Marsden and Missionaries, thus strengthening the relationship between Ngāpuhi and Pākeha. -

Mission Aligned Investment

The report from the Motion 11 Small Working Group as commissioned by the Anglican General Synod (AGS) 2018. Submitted and presented to AGS May 2020. He waka eke noa – A waka we are all in together Fruitful Stewardship through Mission Aligned Investment The essence of this report was distilled into its first draft on the day and at the location from which this photo was taken, looking across the Bay of Islands towards Purerua Peninsular and Oihi where the gospel was first preached by Marsden in 1814 with the invitation and translation of NgāpuhiPage 1 leader Ruatara. Table of Contents PAGE NUMBER 1. Mihi, Introduction and Context 3 2. Executive Summary 10 3. Theological underpinning for Mission Aligned 11 Investment and fruitful stewardship/kaitiakitanga hua 4. Examples of resource sharing with “trust wealth” from 12 the story of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa New Zealand and the Pacific 5. Investment World Developments – the growth of 15 Responsible Investment and Impact Investment 6. Trustee Duties and Obligations 17 7. Legislative context and changes 18 8. Bringing it together – what it all means for Trustees 19 9. Assets of the Anglican Church 21 10. Concluding Comments 25 Appendix A: 26 Australian Christian Super—a relevant exemplar Appendix B: 29 Church of England Commissioners stance on Mission Aligned Investment Appendix C: 32 Motion 11 wording Appendix D: 33 Motion 11 Small Working Group team members and further acknowledgements Appendix E: 34 References MOTION 11 REPORT PAGE 2 1. Mihi, Introduction and Context Te mea tuatahi, Kia whakakorōriatia ki Te Atua i runga rawa Kia mau te rongo ki runga ki te whenua Kia pai te whakaaro ki ngā tāngata katoa Ki ngā mema o Te Hīnota Whānui o Te Hāhi Mihinare ki Aotearoa, ki Niu Tīreni, ki ngā Moutere o te Moana Nui a Kiwa, Tēnā koutou. -

The Development of Maori Christianity in the Waiapu Diocese Until 1914

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. --· · - ~ 'l'he DeYelopment ot Maori Christianity in the Waiapu Dicceee Until 1911t. By Iala L. Prater B.A. Dip.Ed. Maaa~ Un1Yera11'Y A theaia preaented in partial t\11.f"ilment ot the requirementa ot the c!.egree of Maater of A.rte in Hiatory. ACXNOWLEOOEONTS Appreciation ia expressed to thoae who haTe aaaiatecl with thi• theeia J to Protuaor w.H.OliTer tor hi• adnoe regardirla th• material to be uaed, auggeationa on how to huAl• it, aa well a1 help giffll and intereat ahown at ftrioua •tac•• during ita preparation; to the Seoretar.r ot the Napier Diooeaon Office, Mr. Naah tor the UM ot Synod Year booka an4 other material• on aneral ooouiona; to the Biahop ot Aotearoa, Biahop • · Bennett tor hia interriftJ to -ay friend Iii•• T. ti;"era tor aHi•tin« w1 th ao• ~ the 1eoon4 oopiea; to rq Aunt, the lat e Miaa L.G. Jteya tor her •noouragement and interest throughout; and to xra.E.IJnoh tor the exaoting work ot producing the 1'4Jpe-written copi••• n Table of Contents Prefaoe Page Introduction 1 Chapter I Early Indigenisation of' Christianity : the 1830a 5 Chapter II Further Maori Initiative and Responsibility : the 1&..0a 12 Chapter III Consolidation of an Unofficial Maori Church : the 1850s 21 Chapter IV Maori Responaibili ty Culminating in Autonomy : the Early 1860s 31 Chapter V Aa By Fire : The Poat-War Maori Church Until 1914 39 Chapter VI Other Sheep : Poat-War Unorthodox MoTementa Until 1914 54. -

Proposed Gisborne Regional Freshwater Plan

Contents Part A: Introduction and Definitions Schedule 9: Aquifers in the Gisborne Region 161 Section 1: Introduction and How the Plan Works 3 Schedule 10: Culvert Construction Guidelines for Council Administered Drainage Areas 162 Section 2: Definitions 5 Schedule 11: Requirements of Farm Environment Plans 164 Part B: Regional Policy Statement for Freshwater Schedule 12: Bore Construction Requirements 166 Section 3: Regional Policy Statement For Freshwater 31 Schedule 13: Irrigation Management Plan Requirements 174 Part C: Regional Freshwater Plan Schedule 14: Clearances, Setbacks and Maximum Slope Gradients for Installation Section 4: Water Quantity and Allocation 42 of Disposal Systems 175 Section 5: Water Quality and Discharges to Water and Land 48 Schedule 15: Wastewater Flow Allowances 177 Section 6: Activities in the Beds of Rivers and Lakes 83 Schedule 16: Unreticulated Wasterwater Treatment, Storage and Disposal Systems 181 Section 7: Riparian Margins, Wetlands 100 Schedule 17: Wetland Management Plans 182 Part D: Regional Schedules Schedule 18: Requirements for AEE for Emergency Wastewater Overflows 183 Schedule 1: Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies 109 Schedule 19: Guidance for Resource Consent Applications 185 1 Schedule 2: Migrating and Spawning Habitats of Native Fish 124 Part E: Catchment Plans Proposed Schedule 3: Regionally Significant Wetlands 126 General Catchment Plans 190 Schedule 4: Outstanding Waterbodies 128 Waipaoa Catchment Plan 192 Gisborne Schedule 5: Significant Recreation Areas 130 Appendix - Maps for the Regional Freshwater Plan Schedule 6: Watercourses in Land Drainage Areas with Ecological Values 133 Regional Appendix - Maps for the Regional Freshwater Plan 218 Schedule 7: Protected Watercourses 134 Freshwater Schedule 8: Marine Areas of Coastal Significance as Defined in the Coastal Environment Plan 160 Plan Part A: Introduction and Definitions 2 Section 1: Introduction and How the Plan Works 1.0 Introduction and How the Plan Works Part A is comprised of the introduction, how the plan works and definitions. -

Destination Choice of Heritage Attractions in New

Spoiled for choice! Which sites shall we visit? : Destination Choice of Heritage Attractions In New Zealand’s Bay of Islands Takeyuki Morita A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Of Master of International Tourism Management (MITM) 2014 FACULTY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY SCHOOL OF HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM Supervisor: DR CHARLES JOHNSTON Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. ii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. iii Attestation of Authorship ............................................................................................................... iv Ethics Approval .............................................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... vi Abbreviations .............................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ......................................................................................................................................... ix CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. -

Mission Film Script-Word

A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Creative Writing. 8 November 2002, revised April 2016 Sophia (Sophie) Charlotte Rose Jerram PO Box 11 517 Wellington New Zealand i 1 Mission Notes on storv and location This film is set in two locations and in two time zones. It tells a story concerning inter-racial, same-sex love, and the control of imagemaking. A. The past story, 1828-1836 is loosely based on the true story of New Zealand Missionary William Yate and his lover, Eruera Pare Hongi. It is mostly set in Northland, New Zealand, and focuses on the inland Waimate North Mission and surrounding Maori settlement. B. The present day story is a fictional account of Riki Te Awata and an English Photographer, Jeffrey Edison. It is mostly set in the community around a coastal marae and a derelict Southern Mission.1 Sophie Jerram November 2002 1 Unlike the Waimate Mission, this ‘Southern Mission’ is fictional. It was originally intended to be the Puriri mission, at the base of the Coromandel Peninsular, established by William Yate in 1834. Since the coastal mission I have set the film in is nothing like Puriri I have dropped the name. i EXT. PORT JACKSON 1836, DAY A painted image (of the John Gully School) of the historical port of Sydney fills the entire screen. It depicts a number of ships: whaling, convict and trade vessels. The land is busy with diverse groups of people conducting business: traders, convicts, prostitutes, clergymen. -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

KIWI BIBLE HEROES Te Pahi

KIWI BIBLE HEROES Te Pahi Te Pahi was one of the most powerful chiefs in the Bay of Islands at the turn of the 19th century. His principal pa was on Te Puna, an Island situated between Rangihoua and Moturoa. He had several wives, five sons and three daughters. Having heard great reports of Governor Phillip King on Norfolk Island, Te Pahi set sail in 1805 with his four sons to meet him. The ship’s master treated Te Pahi and his family poorly during the trip and on arrival decided to retain one of his sons as payments for the journey. To make matters worse, Te Pahi discovered that King had now become the Governor of New South Wales and was no longer on Norfolk Island. Captain Piper, who was now the authority on Norfolk Island, used his powers to rescue Te Pahi and his sons and treated them kindly until the arrival of the Buffalo. Te Pahi and his sons continued their journey to Sydney on the Buffalo in their quest to meet King. In Sydney they were taken to King’s residence where they presented him with gifts from New Zealand. During their stay in Sydney, Te Pahi attended the church at Parramatta conducted by Samuel Marsden. Te Pahi had long conversations with Marsden about spiritual Sources: matters and showed particular interest in the Christian http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/1t53/te-pahi accessed May 21, 2014 God. Marsden became impressed with the chief’s Keith Newman, Bible and Treaty, Penguin, 2010 Harris, George Prideaux Robert, 1775-1840 :Tippahee a New Zealand chief / strong, clear mind. -

Confirmations at Pentecost 21St Century(The Priest

Issue 58 July 2013 Bishop David with Dora, Sandra, Rachel and Debra Dondi at Hiona St Stephen's, Opotiki. 8th century nave, 13th century sanctuary, Confirmations at Pentecost 21st century(the priest. Church, St Marynot the the priest) Virgin, Bibury ne of the features of Pentecost this year was, appropriately, two confirmation services in West Rotorua Also in this issue and Ōpōtiki. Confirmation has become somewhat invisible over the last few years so it is an encourag- St Hilda's, Abbotsford exhibition Oing sign when we have young people wanting to affirm their faith and be commissioned to serve Christ in Editor in the UK their everyday lives. 100 years in Tolaga Bay Bishop David looks forward to more bookings for confirmation in the months ahead and encourages all parishes Bishop John Bluck back home to include this in their annual calendar. the ball better or the basket seems bigger or the hole larger. I sometimes wonder if Brian’s zone is his ability to frame whatever situation and circumstance with beautiful simplicity. I am not for a moment calling Brian simple or ordinary, to the contrary, he has From Bishop David a wonderful gift. And the second occasion was a few years ago when Brian asked to speak to me regarding his remaining years in Te Puke. What I remember most about this exchange was his excitement. Brian said there was so much to be done, he was enthused about he day was Trinity Sunday. The place was St John the Baptist, riding his kayak-in-waiting in Papamoa, fishing for whatever is to “missional possibilities.” He was invigorated by what he was Te Puke. -

Completed Thesis 30 May 2012

‘In quietness and in confidence shall be your strength’: Vicesimus Lush and his Journals, 1850-1882. A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Gillian Nelson 2012 Thesis title: ‘Vicesimus Lush, M.A.’ Church Gazette, for the Dioceses of Auckland and Melanesia from July 1881 to June 1884, Auckland, 1 August 1882, p.75, AADA. Cover photograph from the collection of Ewelme Cottage © New Zealand Historic Places Trust Pouhere Taonga. iii Abstract !From his arrival in New Zealand in 1850 until his death in 1882 Reverend Vicesimus Lush kept a regular journal to send to family back “home” in England. These journals chronicle the life of an ordinary priest and settler in the Auckland region, his work, relationships and observations. This thesis examines the journals as texts: their role in correspondence and maintaining connections with family. Using Lush’s record of day-to-day experiences, the thesis deals with his emotional attachment towards various expressions of “home” (immediate and extended family, houses, relationship with English land and customs) and explores his associated sense of belonging. !Lush’s role as a priest within the New Zealand Anglican Church also informed his writing. Witnessing and participating in the “building” of the Anglican Church in New Zealand, Lush provided a record of parochial, diocesan and countrywide problems. Lush’s journals track the Anglican Church’s financial struggles, from providing stable salaries to financing church buildings. “Building” the Church required constructing churches and building congregations, adapting liturgical traditions and encouraging the development of a uniquely M"ori church. -

Landmark of Faith – Johnsonville Anglican Church

LANDMARK OF FAITH View across Johnsonville from South 1997 St John’s interior view 1997 A SHORT HISTORY OF ST. JOHN’S ANGICLAN CHURCH JOHNSONVILLE 1847 – 1997 ORIGINAL SHORT HISTORY OF ST. JOHN'S ANGLICAN CHURCH JOHNSONVILLE, NEW ZEALAND, BY THE REV. J.B. ARLIDGE, B.A. WITH ADDED MATERIAL 1925 - 1997 BY J.P. BENTALL' A.N.Z.I.A. Published by St. John's Church Johnsonville, Wellington, New Zealand © 1997, 2014 ISBNs: 0-473-05011-0 (original print version) 978-0-473-29319-2 (mobi) 978-0-473-29320-8 (pdf)\ 978-0-473-29317-8 (epub) 978-0-473-29317-8 (kindle) Original publication typeset and printed by Fisher Print Ltd Electronic version compiled and laid out by David Earle Page 2 CONTENTS INDEX OF LINE DRAWINGS IN THIS BOOKLET WHICH ILLUSTRATE ITEMS USED AT ST. JOHN'S .... 4 FOREWORD .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 1972 PROLOGUE AT THB 125TH ANNIVERSARY ............................................................................................. 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................................ 8 CHAPTER 1: EARLY DAYS 1847 - 1855 ................................................................................................................ 9 THE FIRST CHURCH ............................................................................................................................................................. -

BISHOP GEORGE A. SELWYN Papers, 1831-1952 Reels M590, M1093-1100

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT BISHOP GEORGE A. SELWYN Papers, 1831-1952 Reels M590, M1093-1100 Selwyn College Grange Road Cambridge CB3 9DQ National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1965, 1979 CONTENTS Page 3 Biographical notes Reel M590 4 Journals and other papers of Bishop Selwyn, 1843-57 5 Addresses presented to Bishop Selwyn, 1868-71 5 Letters of Sarah Selwyn, 1842-62 7 Miscellaneous papers, 1831-1906 Reels M1093-1100 8 Correspondence and other papers, 1831-78 26 Pictures and printed items 26 Sermons of Bishop Selwyn 27 Letters and papers of Sarah Selwyn, 1843-1907 28 Correspondence of other clergy and other papers, 1841-97 29 Letterbook, 1840-60 35 Journals and other papers of Bishop Selwyn, 1845-92 36 Letters patent and other papers BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES George Augustus Selwyn (1809-1878) was born in London, the son of William Selwyn, K.C. He was educated at Eton and St John’s College, Cambridge, graduating as a B.A. in 1831 and a M.A. in 1834. He was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1834 and served in the parish of Windsor. He married Sarah Richardson in 1838. He was consecrated the first Bishop of New Zealand on 17 October 1841 and left for New Zealand in December 1841. He was first based at Waimate, near the Bay of Islands, and immediately began the arduous journeys that were a feature of his bishopric. He moved to Auckland in 1844. In 1847-51 he made annual cruises to the islands of Melanesia. Selwyn visited England in 1854-55 and enlisted the services of the Reverend John Patteson, the future Bishop of Melanesia, and secured a missionary schooner, Southern Cross.