Natural Factors but Not Anthropogenic Factors Affect Native and Non–Native Mammal Distribution in a Brazilian National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

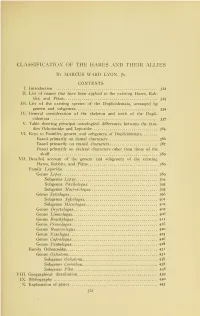

Classification of the Hares and Their Allies

1 CLASSIFICATION OF THE HARES AND THEIR ALLIES By MARCUS WARD LYON, Jr. CONTENTS I. Introduction 322 II. List of names that have been applied to the existing Hares, Rab- bits, and Pikas 325 III. List of the existing species of the DupHcidentata, arranged by genera and subgenera 334 IV. General consideration of the skeleton and teeth of the DupH- cidentata 337 V. Table showing principal osteological differences between the fam- ilies Ochotonida: and Leporidje 384 VI. Keys to Families, genera, and subgenera of DupHcidentata Based primarily on dental characters 386 Based primarily on cranial characters 387 Based primarily on skeletal characters other than those of the skull 389 VII. Detailed account of the genera and subgenera of the existing Hares, Rabbits, and Pikas 389 Family Leporidae Genus Lepits 389 Subgenus Lepus 394 Subgenus Poccilolagus 395 Subgenus Macrofolagiis 395 Genus Sylvilagus 396 Subgenus Sylvilagus 401 Subgenus Microlagus 402 Genus Oryctolagus 402 Genus Linuiolagiis 406 Genus Bracliylagus 4" Genus Pronolagus 416 Genus Romerolagus 420 Genus Nesolagiis 425 Genus Caprolagiis 426 Genus Pentalagus 428 Family Ochotonidae 43 Genus Ochotona 43' Subgenus Ochotona 43^ Subgenus Conothoa 43^ Subgenus Pika 43^ VIII. Geographical distribution 439 IX. Bibliography 44° X. Explanation of plates 443 321 : 32 2 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS [vOL. 45 I. INTRODUCTION The object of this paper is to give an account of the principal osteological features of the hares, rabbits, and pikas or duphcidentate rodents, the DnpHcidentata, and to determine their family, generic, and subgeneric relationships. The subject is treated in two ways. First, there is a discussion of each part of the skeleton and of the variations that are found in that part throughout the various groups of the existing Dupliciden- tata. -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019)

IUCN Red List version 2019-3: Table 7 Last Updated: 10 December 2019 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2018 (IUCN Red List version 2018-2) and 2019 (IUCN Red List version 2019-3) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered [CR(PE) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), CR(PEW) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct in the Wild)], EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2018) List (2019) change version Category -

Appendix Lagomorph Species: Geographical Distribution and Conservation Status

Appendix Lagomorph Species: Geographical Distribution and Conservation Status PAULO C. ALVES1* AND KLAUS HACKLÄNDER2 Lagomorph taxonomy is traditionally controversy, and as a consequence the number of species varies according to different publications. Although this can be due to the conservative characteristic of some morphological and genetic traits, like general shape and number of chromosomes, the scarce knowledge on several species is probably the main reason for this controversy. Also, some species have been discovered only recently, and from others we miss any information since they have been first described (mainly in pikas). We struggled with this difficulty during the work on this book, and decide to include a list of lagomorph species (Table 1). As a reference, we used the recent list published by Hoffmann and Smith (2005) in the “Mammals of the world” (Wilson and Reeder, 2005). However, to make an updated list, we include some significant published data (Friedmann and Daly 2004) and the contribu- tions and comments of some lagomorph specialist, namely Andrew Smith, John Litvaitis, Terrence Robinson, Andrew Smith, Franz Suchentrunk, and from the Mexican lagomorph association, AMCELA. We also include sum- mary information about the geographical range of all species and the current IUCN conservation status. Inevitably, this list still contains some incorrect information. However, a permanently updated lagomorph list will be pro- vided via the World Lagomorph Society (www.worldlagomorphsociety.org). 1 CIBIO, Centro de Investigaça˜o em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos and Faculdade de Ciˆencias, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vaira˜o 4485-661 – Vaira˜o, Portugal 2 Institute of Wildlife Biology and Game Management, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Gregor-Mendel-Str. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

PROCEEDINGS OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM issued B^^fVvi Ol^n by the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION U S NATIONAL MUSEUM Vol. 100 Washington: 1950 No. 3265 MAMAIALS OF NORTHERN COLOMBIA PRELIMINARY REPORT NO. 6: RABBITS (LEPORIDAE), WITH NOTES ON THE CLASSIFICATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN FORMS By Philip Hershkovitz Rabbits collected by the author in northern Colombia during his tenure of the Walter Rathbone Bacon Traveling Scholarship include 18 tapitis representing Sylvilagus brasiliensis and 73 cottontails repre- senting Sylvilagus Jloridanus. The following review shows the above named to be the only recognizably vahd species of leporids indigenous to South America. All North and South American rabbits in the collection of the United States National Museum and the Chicago Natural History Museum were compared in preparing this report. Examples of Neotropical rabbits from other institutions, given below, were also examined. Available material included 34 of the 36 preserved types of South American rabbits. In the lists of specimens examined, the following abbreviations are used: A.M.N.H. American Museum of Natural History. B.M. British Museum (Natural History). CM. Carnegie Museum. C.N.H.M. Chicago Natural History Museum. M.N. H.N. Mus6um National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris. U.M.M.Z. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. U.S.N. M. United States National Museum. Z.M.T. Zoological Museum, Tring. 853011—50 1 327 328 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. lOO The author expresses his appreciation to the authorities of European museums hsted above for permission to study specimens in their charge. Loan of material from American institutions is gratefully acknowl- edged. -

Morphological and Chromosomal Taxonomic Assessment of Sylvilagus Brasiliensis Gabbi (Leporidae)

Article in press - uncorrected proof Mammalia (2007): 63–69 ᮊ 2007 by Walter de Gruyter • Berlin • New York. DOI 10.1515/MAMM.2007.011 Morphological and chromosomal taxonomic assessment of Sylvilagus brasiliensis gabbi (Leporidae) Luis A. Ruedas1,* and Jorge Salazar-Bravo2 species are recognized (Hoffmann and Smith 2005). Syl- vilagus brasiliensis as thus construed is distributed from 1 Museum of Vertebrate Biology and Department of east central Mexico to northern Argentina at elevations Biology, Portland State University, Portland, from sea level to 4800 m, inhabiting biomes ranging from OR 97207-0751, USA, e-mail: [email protected] dry Chaco, through mesic forest, to highland Pa´ ramo 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech (Figure 1). University, Lubbock, TX 79409-3131, USA Most of the junior synonyms of S. brasiliensis currently *Corresponding author represent South American taxa, with Mesoamerican forms grouped into only two recognized subspecies: S. b. gabbi and S. b. truei (Hoffmann and Smith 2005). Based Abstract on specimens from Costa Rica and Panama, Allen (1877) described Lepus brasiliensis var. gabbi, which subse- The cottontail rabbit species, Sylvilagus brasiliensis,is quently was raised to species status (Lepus gabbi)by currently understood to be constituted by 18 subspecies Alston (1882) based on ‘‘differences in lengths of ear and ranging from east central Mexico to northern Argentina, tail between Central American and Brazilian (cottontails)’’. and from sea level to at least 4800 m in altitude. This Lyon (1904), with no further comment, included S. gabbi hypothesis of a single widespread polytypic species as a valid species in Sylvilagus, together with numerous remains to be critically tested. -

First Record for Uruará, South Western Para State, Amazonia, Brazil

International Journal of Research Studies in Biosciences (IJRSB) Volume 5, Issue 6, June 2017, PP 1-3 ISSN 2349-0357 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0365 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0365.0506001 www.arcjournals.org Sylvilagus Brasiliensis (Linnaeus 1758) (Mammalia, Lagomorpha, Leporidae): First Record for Uruará, South Western Para State, Amazonia, Brazil Roberto Portella de Andrade, Emil José Hernández-Ruz 1Curso de Pós-graduação em Biodiversidade e Conservação. Universidade Federal do Pará, Campus Universitário de Altamira. Rua Coronel José Porfírio, Altamira, Pará, Brazil Abstract: We present the first record of Sylvilagus brasiliensis to Uruará, south western Para State, Brazil. This location is outside the known distribution of species and also outside the domain of the Cerrado biome, which is usually associated with the geographic distribution of S. brasiliensis. The tapeti (Sylvilagus brasiliensis), Brazilian cottontail or forest cottontail is a rabbit 20-40 cm long (without the tail), and the adult individual may, weigh from 450 to up to 1,200 g. Their ears are short (40-61 mm) and his big dark eyes. It has elongated hind legs with four fingers while the former are shorter and five fingers. It features short, dense coat; brownish on the back and lighter on the belly. There are also sexual dimorphism, with females larger [1]. This species occurs from Tamaluipas South, Mexico along the east coast of Mexico (excluding the states of Yucatan, Quintana Roo, Campeche and) through Guatemala, (possibly) El Salvador, Honduras, eastern Nicaragua, eastern Costa Rica, Panama and through the northern half of South America (except at high altitudes), including Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, northern Argentina and most of Brazil. -

First Camera Trap Record of Bush Dogs in the State of São Paulo, Brazil

Beisiegel Bush dogs in S ão Paulo Canid News Copyright © 2009 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478 -2677 The following is the established format for referencing this article: Beisiegel, B.M. 2009. First camera trap records of bush dogs in the state of S ão Paulo, Brazil. Canid News 12.5 [online] URL: http://www.canids.org/canidnews/12/Bush_dogs_in_Sao_Paulo.pdf. Field Report First camera trap record of bush dogs in the state of São Paulo, Brazil Beatriz M. Beisiegel Centro Nacional de Pesquisas para a Conservação dos PrePre dadores Naturais – CENAP / ICMBio. Av. dos Bandeirantes, s/n, Balneário Municipal, AtiAtibaibaia,a, CEP 12.941 -980, SP, Brazil. Email: [email protected] Keywords: Atlantic forest; camera trap ; sampling effort; Speothos venaticus . Abstract Thirteen carnivore species occur at the PECB, and a previous study using th ree camera traps (TM 500, Trail Master), over a two year period A picture of a bush dog Speothos venaticus pair obtained pictures of five of them ( crab-eating was obtained with a minimum sampling effort raccoon Procyon cancrivorus , puma Puma con- of 4,818 camera days, using seven to ten cam- color , ring-tailed coati Nasua nasua , neotropical era traps during 922 days at Parque Estadual river otter Lontra longicaudis and ocelot Leopar- Carlos Botelho, an Atlantic forest site. This dus pardalis - Beisiegel 1999). In the current picture confirms the presence of the species in study, a continuous sampling effort using the state of São Paulo, Brazil. seven to ten camera traps (Tigrinus 4.0 C, Br a- zil) begun in May 2006. -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12. -

The Global Invasive Species Programme

GISP The Global Invasive Species Programme CONTENTS 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 44 Pigeons 45 European Starling 3 FOREWORD 46 Monk Parakeet 47 California Quail 4 INTRODUCTION TO 48 Red-eared Slider BIOLOGICAL 49 Teiu Lizard INVASIONS 50 Giant African Snail 51 Big-headed Ant 6 INTRODUCTION 51 Little Fire Ant 52 Africanised Bee 14 SOUTH AMERICA 53 European Wasp INVADED 54 AQUATIC INVADERS 15 TREES 54 Ballast Water and Sediment 16 Pines 56 Golden Mussel 18 Acacias 58 Asian Clam 20 Chinaberry 59 Japanese Kelp 21 Japanese Cherry 60 American Bullfrog 21 Loquat 61 African Clawed Frog 22 African Oil Palm 62 Common Carp 23 Tamarisks 64 Tilapia 24 Prosopis 66 Salmonids 25 Leucaena 67 Mosquito Fish 26 SHRUBS 68 INSECT PESTS 26 Castor Oil Plant 68 Coffee Berry Borer 27 Privets 69 Cotton Boll Weevil 28 Blackberries 69 Cottony Cushion Scale 28 Japanese Honeysuckle 70 European Woodwasp 29 Rambling Roses 71 Codling Moth 30 Brooms 31 Gorse 72 SOUTH AMERICA INVADING 32 GRASSES 73 • Water Hyacinth 73 • Alligator Weed 35 ANIMALS 74 • Mile-a-minute Weed 35 Rats 74 • Chromolaena 36 American Beaver 75 • Lantana 37 Mink 75 • Brazilian Peppertree 37 Muskrat 76 • Nutria 38 European Rabbit 76 • Armoured Catfish 39 European Hare 77 • Cane Toad 39 Small Indian Mongoose 78 • Golden Apple Snail 40 Red Deer 78 • Argentine Ant 41 Feral Pigs and Wild Boar 79 • Cassava Green Mite 42 Feral Animals in Galapagos 80 • Larger Grain Borer 44 House Sparrow 80 • Leafminers PAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS © The Global Invasive Species Programme First published in 2005 by the GISP Secretariat ISBN 1-919684-47-6 (Portuguese edition: ISBN 1-919684-48-4) (Spanish edition: ISBN 1-919684-49-2) GISP wants to thank our partner organisations, the World Bank and the many individuals who helped make this publication a reality, giving their time and expertise freely despite busy work schedules and other commitments. -

Introduction to the Lagomorpha

Introduction to the Lagomorpha JOSEPH A. CHAPMAN1 AND JOHN E.C. FLUX2,* Introduction Lagomorphs (pikas, rabbits and hares) are widespread, being native or intro- duced on all continents except Antarctica. They are all herbivores, occupying an unusual size range between the rodents, “small mammals”, and ungulates, “large mammals”. Pikas weigh 75–290 g, rabbits 1–4 kg, and hares 2–5 kg. Despite the small number of extant species relative to rodents, lagomorphs are very successful, occurring from sea level up to over 5,000 m, from the equator to 80 N, and in diverse habitats including tundra, steppe, swamp, and tropical forest. Some species have extremely narrow habitat tolerance, for example the pygmy rabbit (Brachylagus idahoensis) requires dense sagebrush, the riverine rabbit (Bunolagus monticularis) is restricted to Karoo floodplain vegetation, and the volcano rabbit (Romerolagus diazi) to zacaton grassland. On the other hand, the tapeti (Sylvilagus brasiliensis) occurs from alpine grass- land at the snowline to dense equatorial forest on the Amazon, and some hares (Lepus spp.) occupy vast areas. According to the latest review by Hoffmann and Smith (in press), there are about 91 living species, including 30 pikas, 32 hares and 29 rabbits (see Fig. 1, families and genera of living lagomorphs). Taxonomy Lagomorphs were classified as rodents until the Order Lagomorpha was recog- nized in 1912. Anatomically, they can be separated from rodents by a second set of incisors (peg teeth) located directly behind the upper front incisors. The pikas (Ochotonidae) have 26 teeth (dental formula i. 2/1, c. 0/0, p. 3/2, m. -

Rabbits, Hares and Pikas Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan

-Rabbits, Hares and Pikas Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan Compiled and edited by Joseph A. Chapman and John E.C. Flux IUCN/SSC Lagomorph Specialist Group Rabbits, Hares and Pikas Status Survey and Action Plan Compiled and edited by Joseph A. Chapman and John E.C. Flux IUCN/SSC Lagomorph Specialist Group of Oman Foreword The IUCN/SSC Lagomorph Specialist Group was constituted The Lagomorph Group, building on its good start, soon as- in as part of a determined effort by the Species Survival sumed responsibility for providing the information necessary Commission to broaden the base of its activities by incorporat- for preparing and updating lagomorph entries in the Red Data ing a large number of new Groups into its membership. By the Book and for submissions to the Convention on International end of 1979, the Lagomorph Group had attracted from Europe, Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora Asia, Africa, the Americas and the Pacific 19 highly motivated (CITES). It holds a strong position against the introduction of biologists with a concern for problems of conservation of the eastern cottontail to Europe, and has gomorphs in their respective lands, and a willingness to do willingly participated in discussions on the subject when re- something about them. quested. The Group also continues to take the lead in keeping In August 1979, the young Group held its inaugural meeting lagomorphs on conference agenda at international meetings, at the University of Guelph, Ontario, in conjunction with the and has widened its in recent years to look at the status first World Lagomorph Conference. -

Myxoma Virus and the Leporipoxviruses: an Evolutionary Paradigm

Viruses 2015, 7, 1020-1061; doi:10.3390/v7031020 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Review Myxoma Virus and the Leporipoxviruses: An Evolutionary Paradigm Peter J. Kerr 1,†,*, June Liu 1, Isabella Cattadori 2, Elodie Ghedin 3, Andrew F. Read 2 and Edward C. Holmes 4 1 CSIRO Biosecurity Flagship, Black Mountain Laboratories, Clunies Ross Street, Acton, ACT 2601, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics, Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (I.C.); [email protected] (A.F.R.) 3 Center for Genomics and Systems Biology, Department of Biology and Global Institute of Public Health, New York University, New York, NY 10003, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Marie Bashir Institute for Infectious Diseases and Biosecurity, Charles Perkins Centre, School of Biological Sciences, and Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] † Current address: School of Biological Sciences, The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-62464334. Academic Editors: Elliot J. Lefkowitz and Chris Upton Received: 31 December 2014 / Accepted: 26 February 2015 / Published: 6 March 2015 Abstract: Myxoma virus (MYXV) is the type species of the Leporipoxviruses, a genus of Chordopoxvirinae, double stranded DNA viruses, whose members infect leporids and squirrels, inducing cutaneous fibromas from which virus is mechanically transmitted by biting arthropods. However, in the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), MYXV causes the lethal disease myxomatosis.