Swamp Rabbit Sylvilagus Aquaticus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning About Mammals

Learning About Mammals The mammals (Class Mammalia) includes everything from mice to elephants, bats to whales and, of course, man. The amazing diversity of mammals is what has allowed them to live in any habitat from desert to arctic to the deep ocean. They live in trees, they live on the ground, they live underground, and in caves. Some are active during the day (diurnal), while some are active at night (nocturnal) and some are just active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular). They live alone (solitary) or in great herds (gregarious). They mate for life (monogamous) or form harems (polygamous). They eat meat (carnivores), they eat plants (herbivores) and they eat both (omnivores). They fill every niche imaginable. Mammals come in all shapes and sizes from the tiny pygmy shrew, weighing 1/10 of an ounce (2.8 grams), to the blue whale, weighing more than 300,000 pounds! They have a huge variation in life span from a small rodent living one year to an elephant living 70 years. Generally, the bigger the mammal, the longer the life span, except for bats, which are as small as rodents, but can live for up to 20 years. Though huge variation exists in mammals, there are a few physical traits that unite them. 1) Mammals are covered with body hair (fur). Though marine mammals, like dolphins and whales, have traded the benefits of body hair for better aerodynamics for traveling in water, they do still have some bristly hair on their faces (and embryonically - before birth). Hair is important for keeping mammals warm in cold climates, protecting them from sunburn and scratches, and used to warn off others, like when a dog raises the hair on its neck. -

Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide the jill and lewis bernard family Hall of north american mammals inside: • Suggestions to Help You come prepared • essential questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for teaching in the exhibition • map of the Exhibition • online resources for the Classroom • Correlations to science framework • glossary amnh.org/namammals Essential QUESTIONS Who are — and who were — the North as tundra, winters are cold, long, and dark, the growing season American Mammals? is extremely short, and precipitation is low. In contrast, the abundant precipitation and year-round warmth of tropical All mammals on Earth share a common ancestor and and subtropical forests provide optimal growing conditions represent many millions of years of evolution. Most of those that support the greatest diversity of species worldwide. in this hall arose as distinct species in the relatively recent Florida and Mexico contain some subtropical forest. In the past. Their ancestors reached North America at different boreal forest that covers a huge expanse of the continent’s times. Some entered from the north along the Bering land northern latitudes, winters are dry and severe, summers moist bridge, which was intermittently exposed by low sea levels and short, and temperatures between the two range widely. during the Pleistocene (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago). Desert and scrublands are dry and generally warm through- These migrants included relatives of New World cats (e.g. out the year, with temperatures that may exceed 100°F and dip sabertooth, jaguar), certain rodents, musk ox, at least two by 30 degrees at night. kinds of elephants (e.g. -

Classification of the Hares and Their Allies

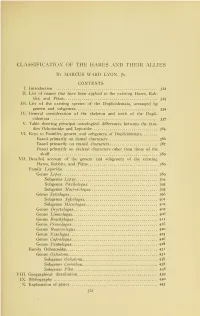

1 CLASSIFICATION OF THE HARES AND THEIR ALLIES By MARCUS WARD LYON, Jr. CONTENTS I. Introduction 322 II. List of names that have been applied to the existing Hares, Rab- bits, and Pikas 325 III. List of the existing species of the DupHcidentata, arranged by genera and subgenera 334 IV. General consideration of the skeleton and teeth of the DupH- cidentata 337 V. Table showing principal osteological differences between the fam- ilies Ochotonida: and Leporidje 384 VI. Keys to Families, genera, and subgenera of DupHcidentata Based primarily on dental characters 386 Based primarily on cranial characters 387 Based primarily on skeletal characters other than those of the skull 389 VII. Detailed account of the genera and subgenera of the existing Hares, Rabbits, and Pikas 389 Family Leporidae Genus Lepits 389 Subgenus Lepus 394 Subgenus Poccilolagus 395 Subgenus Macrofolagiis 395 Genus Sylvilagus 396 Subgenus Sylvilagus 401 Subgenus Microlagus 402 Genus Oryctolagus 402 Genus Linuiolagiis 406 Genus Bracliylagus 4" Genus Pronolagus 416 Genus Romerolagus 420 Genus Nesolagiis 425 Genus Caprolagiis 426 Genus Pentalagus 428 Family Ochotonidae 43 Genus Ochotona 43' Subgenus Ochotona 43^ Subgenus Conothoa 43^ Subgenus Pika 43^ VIII. Geographical distribution 439 IX. Bibliography 44° X. Explanation of plates 443 321 : 32 2 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS [vOL. 45 I. INTRODUCTION The object of this paper is to give an account of the principal osteological features of the hares, rabbits, and pikas or duphcidentate rodents, the DnpHcidentata, and to determine their family, generic, and subgeneric relationships. The subject is treated in two ways. First, there is a discussion of each part of the skeleton and of the variations that are found in that part throughout the various groups of the existing Dupliciden- tata. -

Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Annual Report 1 Our Mission Ohio Wildlife Center is dedicated to fostering awareness and appreciation of Ohio’s native wildlife through rehabilitation, education and wildlife health studies. Table of Contents Our Work The Center operates the state’s largest, free native 2 Our Mission and Work wildlife animal hospital, which assessed and treated 3 Message from the Board Chair 4,525 wildlife patients from 54 Ohio counties in 2016. Now a statewide leader in wildlife animal rescue and and Executive Director rehabilitation, the Center includes a 20-acre outdoor 4 2016 Fast Facts for Wildlife Hospital Education Center and Pre-Release Facility in Delaware County. The free Wildlife Hospital is located in the lower 5 2016 Fast Facts for Education level of Animal Care Unlimited at 2661 Billingsley 6 Foundation Grants and Partnerships Road in Columbus. 7 Volunteer Impact A focal point of the Education Center is the permanent sanctuary for 59 animals, ranging from coyote and fox 8 The Barbara and Bill Bonner Family to hawks, owls, raccoons, turtles and a turkey. There Foundation Barn are 42 species represented and seven animal ambassador 9 Power of Partnerships species listed as threatened or species of concern in Ohio. 10 2016 Events The Pre-Release Facility is comprised of multiple flight enclosures, a waterfowl enclosure, a songbird aviary, 11 Financials and species-specific outdoor housing designed to 12 Wildlife Hospital Admissions support the final phase of rehabilitation for recovering hospital patients. Animals reside at the Pre-Release 14 Board of Trustees Facility with care and oversight as they acclimate to the 15 Thank you! elements. -

Late Miocene Fossil Calibration from Yunnan Province for the Striped Rabbit Nesolagus Lawrence J

第57卷 第3期 古 脊 椎 动 物 学 报 pp. 214–224 figs. 1–8 2019年7月 VERTEBRATA PALASIATICA DOI: 10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.190326 Late Miocene fossil calibration from Yunnan Province for the striped rabbit Nesolagus Lawrence J. FLYNN1 JIN Chang-Zhu2 Jay KELLEY3,4 Nina G. JABLONSKI5 JI Xue-Ping6 Denise F. SU7 DENG Tao2,8,9 LI Qiang2,8 (1 Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Cambridge MA 02138, USA [email protected]) (2 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100044, China) (3 Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287, USA) (4 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC 20560, USA) (5 Department of Anthropology, The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802, USA) (6 Department of Paleoanthropology, Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology Kunming 650118, China) (7 Department of Paleobotany and Paleoecology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History Cleveland, OH 44106, USA) (8 CAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment Beijing 100044, China) (9 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100049, China) Abstract The rabbit from the Late Miocene Shuitangba site in Yunnan Province represents the same species as that from the older site of Lufeng, Yunnan. Both settings record a wet, swampy habitat. Premolar morphology shows that the species is an early representative of the extant striped rabbit genus, which today lives in moist habitat, and should be designated Nesolagus longisinuosus (Qiu & Han, 1986). -

Cottontail Rabbits

Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States Photo Credit, Sky deLight Credit,Photo Sky Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8 Western Golden Eagle Team Front Matter Date: November 13, 2017 Disclaimer The reports in this series have been prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) Western Golden Eagle Team (WGET) for the purpose of proactively addressing energy-related conservation needs of golden eagles in Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8. The team was composed of Service personnel, sometimes assisted by contractors or outside cooperators. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Suggested Citation Hansen, D.L., G. Bedrosian, and G. Beatty. 2017. Biology of cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as prey of golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States. Unpublished report prepared by the Western Golden Eagle Team, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Available online at: https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/Reference/Profile/87137 Acknowledgments This report was authored by Dan L. Hansen, Geoffrey Bedrosian, and Greg Beatty. The authors are grateful to the following reviewers (in alphabetical order): Katie Powell, Charles R. Preston, and Hillary White. Cottontails—i Summary Cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.; hereafter, cottontails) are among the most frequently identified prey in the diets of breeding golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States (U.S.). -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019)

IUCN Red List version 2019-3: Table 7 Last Updated: 10 December 2019 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2018 (IUCN Red List version 2018-2) and 2019 (IUCN Red List version 2019-3) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered [CR(PE) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), CR(PEW) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct in the Wild)], EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2018) List (2019) change version Category -

Ecography ECOG-01063 Verde Arregoitia, L

Ecography ECOG-01063 Verde Arregoitia, L. D., Leach, K., Reid, N. and Fisher, D. O. 2015. Diversity, extinction, and threat status in Lagomorphs. – Ecography doi: 10.1111/ecog.01063 Supplementary material 1 Appendix 1 2 Paleobiogeographic summaries for all extant lagomorph genera. 3 4 Pikas – Family Ochotonidae 5 The maximum diversity and geographic extent of pikas occurred during the global climate 6 optimum from the late-Oligocene to middle-Miocene (Ge et al. 2012). When species evolve 7 and diversify at higher temperatures, opportunities for speciation and evolution of thermal 8 niches are likely through adaptive radiation in relatively colder and species poor areas 9 (Araújo et al. 2013). Extant Ochotonids may be marginal (ecologically and geographically) 10 but diverse because they occur in topographically complex areas where habitat diversity is 11 greater and landscape units are smaller (Shvarts et al. 1995). Topographical complexity 12 creates new habitat, enlarges environmental gradients, establishes barriers to dispersal, and 13 isolates populations. All these conditions can contribute to adaptation to new environmental 14 conditions and speciation in excess of extinction for terrestrial species (Badgley 2010). 15 16 Hares and rabbits - Family Leporidae 17 Pronolagus, Bunolagus, Romerolagus, Pentalagus and Nesolagus may belong to lineages 18 that were abundant and widespread in the Oligocene and subsequently lost most (if not all) 19 species. Lepus, Sylvilagus, Caprolagus and Oryctolagus represent more recent radiations 20 which lost species unevenly during the late Pleistocene. Living species in these four genera 21 display more generalist diet and habitat preferences, and are better represented in the fossil 22 record. (Lopez-Martinez 2008). -

Colorado Field Ornithologists the Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly

Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists The Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly VOL. 36, NO. 1 Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists January 2002 Vol. 36, No. 1 Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists January 2002 TABLE OF C ONTENTS A LETTER FROM THE E DITOR..............................................................................................2 2002 CONVENTION IN DURANGO WITH KENN KAUFMANN...................................................3 CFO BOARD MEETING MINUTES: 1 DECEMBER 2001........................................................4 TREE-NESTING HABITAT OF PURPLE MARTINS IN COLORADO.................................................6 Richard T. Reynolds, David P. Kane, and Deborah M. Finch OLIN SEWALL PETTINGILL, JR.: AN APPRECIATION...........................................................14 Paul Baicich MAMMALS IN GREAT HORNED OWL PELLETS FROM BOULDER COUNTY, COLORADO............16 Rebecca E. Marvil and Alexander Cruz UPCOMING CFO FIELD TRIPS.........................................................................................23 THE SHRIKES OF DEARING ROAD, EL PASO COUNTY, COLORADO 1993-2001....................24 Susan H. Craig RING-BILLED GULLS FEEDING ON RUSSIAN-OLIVE FRUIT...................................................32 Nicholas Komar NEWS FROM THE C OLORADO BIRD R ECORDS COMMITTEE (JANUARY 2002).........................35 Tony Leukering NEWS FROM THE FIELD: THE SUMMER 2001 REPORT (JUNE - JULY)...................................36 Christopher L. Wood and Lawrence S. Semo COLORADO F IELD O -

World Distribution of the European Rabbit (Oryctolagus Cuniculus)

1 The Evolution, Domestication and World Distribution of the European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) Luca Fontanesi1*, Valerio Joe Utzeri1 and Anisa Ribani1 1Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Bologna, Italy 1.1 The Order Lagomorpha to assure essential vitamin uptake, the digestion of the vegetarian diet and water reintroduction The European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus, (Hörnicke, 1981). Linnaeus 1758) is a mammal belonging to the The order Lagomorpha was recognized as a order Lagomorpha. distinct order within the class Mammalia in Lagomorphs are such a distinct group of 1912, separated from the order Rodentia within mammalian herbivores that the very word ‘lago- which lagomorphs were originally placed (Gidely, morph’ is a circular reference meaning ‘hare- 1912; Landry, 1999). Lagomorphs are, however, shaped’ (Chapman and Flux, 1990; Fontanesi considered to be closely related to the rodents et al., 2016). A unique anatomical feature that from which they diverged about 62–100 million characterizes lagomorphs is the presence of years ago (Mya), and together they constitute small peg-like teeth immediately behind the up- the clade Glires (Chuan-Kuei et al., 1987; Benton per-front incisors. For this feature, lagomorphs and Donoghue, 2007). Lagomorphs, rodents and are also known as Duplicidentata. Therefore, primates are placed in the major mammalian instead of four incisor teeth characteristic of clade of the Euarchontoglires (O’Leary et al., 2013). rodents (also known as Simplicidentata), lago- Modern lagomorphs might be evolved from morphs have six. The additional pair is reduced the ancestral lineage from which derived the in size. Another anatomical characteristic of the †Mimotonidae and †Eurymilydae sister taxa, animals of this order is the presence of an elong- following the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) bound- ated rostrum of the skull, reinforced by a lattice- ary around 65 Mya (Averianov, 1994; Meng et al., work of bone, which is a fenestration to reduce 2003; Asher et al., 2005; López-Martínez, 2008). -

Genomic Analysis Reveals Hidden Biodiversity Within Colugos, the Sister Group to Primates Victor C

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2016 Genomic analysis reveals hidden biodiversity within colugos, the sister group to primates Victor C. Mason Texas A & M University - College Station Gang Li Texas A & M University - College Station Patrick Minx Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Jürgen Schmitz University of Münster Gennady Churakov University of Münster See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Mason, Victor C.; Li, Gang; Minx, Patrick; Schmitz, Jürgen; Churakov, Gennady; Doronina, Liliya; Melin, Amanda D.; Dominy, Nathaniel J.; Lim, Norman T-L; Springer, Mark S.; Wilson, Richard K.; Warren, Wesley C.; Helgen, Kristofer M.; and Murphy, William J., ,"Genomic analysis reveals hidden biodiversity within colugos, the sister group to primates." Science Advances.2,8. e1600633. (2016). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/5209 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Victor C. Mason, Gang Li, Patrick Minx, Jürgen Schmitz, Gennady Churakov, Liliya Doronina, Amanda D. Melin, Nathaniel J. Dominy, Norman T-L Lim, Mark S. Springer, Richard K. Wilson, Wesley C. Warren, Kristofer M. Helgen, and William J. Murphy This open access publication is available at Digital Commons@Becker: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/5209 RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGICAL POPULATION GENETICS 2016 © The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. -

Eastern Cottontail

EASTERN COTTONTAIL This publication is available in alternativeRABBIT media on request. Penn State is an equal opportunity, affirmative action employer, and is committed to providing employment opportunities to all qualified applicants without regard to race, color, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability, or protected veteran status. © The Pennsylvania State University 2017 U.Ed. AGR 17-73 Corner of Park Ave. and Bigler Road • University Park, PA 16802 arboretum.psu.edu facebook.com/pennstatearboretum COTTONTAIL RABBIT DESCRIPTION Named for its characteristic “cotton-ball” tail, the Eastern cottontail is the most widespread species of rabbit in North America. Although most active on rainy or foggy nights, this animal’s brown fur provides excellent camou- NAME: Sylvilagus floridanus flage during the day. Because Eastern cottontails do not hibernate, they can be found in Pennsylvania year-round CONSERVATION STATUS: in open, grassy areas with shrubby cover. The long ears of extinct near least rabbits can move independently, enabling them to hear extinct in wild threatened threatened concern in two directions at once, as well as providing a cooling mechanism through an extensive network of blood vessels. EX EW CR EN VU NT LC DIET SIZE: 1.3–1.5 feet A common visitor to gardens, the Eastern cottontail rabbit enjoys eating grasses, herbs, flowers, fruit, and WEIGHT: 1.75–3.5 pounds vegetables. In the winter, this animal dines on twigs, bark, and plant buds. GROUP TERM: colony; nest THREATS NUMBER OF YOUNG: 3–8 Eastern cottontail rabbits are preyed upon by coyotes, foxes, bobcats, hawks, and even snakes. They may also HABITAT: open fields, meadows be hunted by humans for their meat and fur.