Introduction to the Lagomorpha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification of the Hares and Their Allies

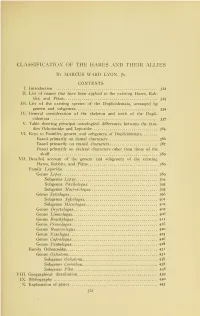

1 CLASSIFICATION OF THE HARES AND THEIR ALLIES By MARCUS WARD LYON, Jr. CONTENTS I. Introduction 322 II. List of names that have been applied to the existing Hares, Rab- bits, and Pikas 325 III. List of the existing species of the DupHcidentata, arranged by genera and subgenera 334 IV. General consideration of the skeleton and teeth of the DupH- cidentata 337 V. Table showing principal osteological differences between the fam- ilies Ochotonida: and Leporidje 384 VI. Keys to Families, genera, and subgenera of DupHcidentata Based primarily on dental characters 386 Based primarily on cranial characters 387 Based primarily on skeletal characters other than those of the skull 389 VII. Detailed account of the genera and subgenera of the existing Hares, Rabbits, and Pikas 389 Family Leporidae Genus Lepits 389 Subgenus Lepus 394 Subgenus Poccilolagus 395 Subgenus Macrofolagiis 395 Genus Sylvilagus 396 Subgenus Sylvilagus 401 Subgenus Microlagus 402 Genus Oryctolagus 402 Genus Linuiolagiis 406 Genus Bracliylagus 4" Genus Pronolagus 416 Genus Romerolagus 420 Genus Nesolagiis 425 Genus Caprolagiis 426 Genus Pentalagus 428 Family Ochotonidae 43 Genus Ochotona 43' Subgenus Ochotona 43^ Subgenus Conothoa 43^ Subgenus Pika 43^ VIII. Geographical distribution 439 IX. Bibliography 44° X. Explanation of plates 443 321 : 32 2 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS [vOL. 45 I. INTRODUCTION The object of this paper is to give an account of the principal osteological features of the hares, rabbits, and pikas or duphcidentate rodents, the DnpHcidentata, and to determine their family, generic, and subgeneric relationships. The subject is treated in two ways. First, there is a discussion of each part of the skeleton and of the variations that are found in that part throughout the various groups of the existing Dupliciden- tata. -

Late Miocene Fossil Calibration from Yunnan Province for the Striped Rabbit Nesolagus Lawrence J

第57卷 第3期 古 脊 椎 动 物 学 报 pp. 214–224 figs. 1–8 2019年7月 VERTEBRATA PALASIATICA DOI: 10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.190326 Late Miocene fossil calibration from Yunnan Province for the striped rabbit Nesolagus Lawrence J. FLYNN1 JIN Chang-Zhu2 Jay KELLEY3,4 Nina G. JABLONSKI5 JI Xue-Ping6 Denise F. SU7 DENG Tao2,8,9 LI Qiang2,8 (1 Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University Cambridge MA 02138, USA [email protected]) (2 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100044, China) (3 Institute of Human Origins and School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Arizona State University Tempe, AZ 85287, USA) (4 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC 20560, USA) (5 Department of Anthropology, The Pennsylvania State University University Park, PA 16802, USA) (6 Department of Paleoanthropology, Yunnan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology Kunming 650118, China) (7 Department of Paleobotany and Paleoecology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History Cleveland, OH 44106, USA) (8 CAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment Beijing 100044, China) (9 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100049, China) Abstract The rabbit from the Late Miocene Shuitangba site in Yunnan Province represents the same species as that from the older site of Lufeng, Yunnan. Both settings record a wet, swampy habitat. Premolar morphology shows that the species is an early representative of the extant striped rabbit genus, which today lives in moist habitat, and should be designated Nesolagus longisinuosus (Qiu & Han, 1986). -

Cottontail Rabbits

Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States Photo Credit, Sky deLight Credit,Photo Sky Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8 Western Golden Eagle Team Front Matter Date: November 13, 2017 Disclaimer The reports in this series have been prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) Western Golden Eagle Team (WGET) for the purpose of proactively addressing energy-related conservation needs of golden eagles in Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8. The team was composed of Service personnel, sometimes assisted by contractors or outside cooperators. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Suggested Citation Hansen, D.L., G. Bedrosian, and G. Beatty. 2017. Biology of cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as prey of golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States. Unpublished report prepared by the Western Golden Eagle Team, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Available online at: https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/Reference/Profile/87137 Acknowledgments This report was authored by Dan L. Hansen, Geoffrey Bedrosian, and Greg Beatty. The authors are grateful to the following reviewers (in alphabetical order): Katie Powell, Charles R. Preston, and Hillary White. Cottontails—i Summary Cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.; hereafter, cottontails) are among the most frequently identified prey in the diets of breeding golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States (U.S.). -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019)

IUCN Red List version 2019-3: Table 7 Last Updated: 10 December 2019 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2018 (IUCN Red List version 2018-2) and 2019 (IUCN Red List version 2019-3) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered [CR(PE) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), CR(PEW) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct in the Wild)], EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2018) List (2019) change version Category -

Ecography ECOG-01063 Verde Arregoitia, L

Ecography ECOG-01063 Verde Arregoitia, L. D., Leach, K., Reid, N. and Fisher, D. O. 2015. Diversity, extinction, and threat status in Lagomorphs. – Ecography doi: 10.1111/ecog.01063 Supplementary material 1 Appendix 1 2 Paleobiogeographic summaries for all extant lagomorph genera. 3 4 Pikas – Family Ochotonidae 5 The maximum diversity and geographic extent of pikas occurred during the global climate 6 optimum from the late-Oligocene to middle-Miocene (Ge et al. 2012). When species evolve 7 and diversify at higher temperatures, opportunities for speciation and evolution of thermal 8 niches are likely through adaptive radiation in relatively colder and species poor areas 9 (Araújo et al. 2013). Extant Ochotonids may be marginal (ecologically and geographically) 10 but diverse because they occur in topographically complex areas where habitat diversity is 11 greater and landscape units are smaller (Shvarts et al. 1995). Topographical complexity 12 creates new habitat, enlarges environmental gradients, establishes barriers to dispersal, and 13 isolates populations. All these conditions can contribute to adaptation to new environmental 14 conditions and speciation in excess of extinction for terrestrial species (Badgley 2010). 15 16 Hares and rabbits - Family Leporidae 17 Pronolagus, Bunolagus, Romerolagus, Pentalagus and Nesolagus may belong to lineages 18 that were abundant and widespread in the Oligocene and subsequently lost most (if not all) 19 species. Lepus, Sylvilagus, Caprolagus and Oryctolagus represent more recent radiations 20 which lost species unevenly during the late Pleistocene. Living species in these four genera 21 display more generalist diet and habitat preferences, and are better represented in the fossil 22 record. (Lopez-Martinez 2008). -

World Distribution of the European Rabbit (Oryctolagus Cuniculus)

1 The Evolution, Domestication and World Distribution of the European Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) Luca Fontanesi1*, Valerio Joe Utzeri1 and Anisa Ribani1 1Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Bologna, Italy 1.1 The Order Lagomorpha to assure essential vitamin uptake, the digestion of the vegetarian diet and water reintroduction The European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus, (Hörnicke, 1981). Linnaeus 1758) is a mammal belonging to the The order Lagomorpha was recognized as a order Lagomorpha. distinct order within the class Mammalia in Lagomorphs are such a distinct group of 1912, separated from the order Rodentia within mammalian herbivores that the very word ‘lago- which lagomorphs were originally placed (Gidely, morph’ is a circular reference meaning ‘hare- 1912; Landry, 1999). Lagomorphs are, however, shaped’ (Chapman and Flux, 1990; Fontanesi considered to be closely related to the rodents et al., 2016). A unique anatomical feature that from which they diverged about 62–100 million characterizes lagomorphs is the presence of years ago (Mya), and together they constitute small peg-like teeth immediately behind the up- the clade Glires (Chuan-Kuei et al., 1987; Benton per-front incisors. For this feature, lagomorphs and Donoghue, 2007). Lagomorphs, rodents and are also known as Duplicidentata. Therefore, primates are placed in the major mammalian instead of four incisor teeth characteristic of clade of the Euarchontoglires (O’Leary et al., 2013). rodents (also known as Simplicidentata), lago- Modern lagomorphs might be evolved from morphs have six. The additional pair is reduced the ancestral lineage from which derived the in size. Another anatomical characteristic of the †Mimotonidae and †Eurymilydae sister taxa, animals of this order is the presence of an elong- following the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) bound- ated rostrum of the skull, reinforced by a lattice- ary around 65 Mya (Averianov, 1994; Meng et al., work of bone, which is a fenestration to reduce 2003; Asher et al., 2005; López-Martínez, 2008). -

Appendix Lagomorph Species: Geographical Distribution and Conservation Status

Appendix Lagomorph Species: Geographical Distribution and Conservation Status PAULO C. ALVES1* AND KLAUS HACKLÄNDER2 Lagomorph taxonomy is traditionally controversy, and as a consequence the number of species varies according to different publications. Although this can be due to the conservative characteristic of some morphological and genetic traits, like general shape and number of chromosomes, the scarce knowledge on several species is probably the main reason for this controversy. Also, some species have been discovered only recently, and from others we miss any information since they have been first described (mainly in pikas). We struggled with this difficulty during the work on this book, and decide to include a list of lagomorph species (Table 1). As a reference, we used the recent list published by Hoffmann and Smith (2005) in the “Mammals of the world” (Wilson and Reeder, 2005). However, to make an updated list, we include some significant published data (Friedmann and Daly 2004) and the contribu- tions and comments of some lagomorph specialist, namely Andrew Smith, John Litvaitis, Terrence Robinson, Andrew Smith, Franz Suchentrunk, and from the Mexican lagomorph association, AMCELA. We also include sum- mary information about the geographical range of all species and the current IUCN conservation status. Inevitably, this list still contains some incorrect information. However, a permanently updated lagomorph list will be pro- vided via the World Lagomorph Society (www.worldlagomorphsociety.org). 1 CIBIO, Centro de Investigaça˜o em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos and Faculdade de Ciˆencias, Universidade do Porto, Campus Agrário de Vaira˜o 4485-661 – Vaira˜o, Portugal 2 Institute of Wildlife Biology and Game Management, University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences, Gregor-Mendel-Str. -

Federal Trade Commission § 301.0

Federal Trade Commission § 301.0 NAME GUIDE § 301.0 Fur products name guide. NAME GUIDE Name Order Family Genus-species Alpaca ...................................... Ungulata ................ Camelidae ............. Lama pacos. Antelope ................................... ......do .................... Bovidae ................. Hippotragus niger and Antilope cervicapra. Badger ..................................... Carnivora ............... Mustelidae ............. Taxida sp. and Meles sp. Bassarisk ................................. ......do .................... Procyonidae .......... Bassariscus astutus. Bear ......................................... ......do .................... Ursidae .................. Ursus sp. Bear, Polar ............................... ......do .................... ......do .................... Thalarctos sp. Beaver ..................................... Rodentia ................ Castoridae ............. Castor canadensis. Burunduk ................................. ......do .................... Sciuridae ............... Eutamias asiaticus. Calf .......................................... Ungulata ................ Bovidae ................. Bos taurus. Cat, Caracal ............................. Carnivora ............... Felidae .................. Caracal caracal. Cat, Domestic .......................... ......do .................... ......do .................... Felis catus. Cat, Lynx ................................. ......do .................... ......do .................... Lynx refus. Cat, Manul .............................. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

PROCEEDINGS OF THE UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM issued B^^fVvi Ol^n by the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION U S NATIONAL MUSEUM Vol. 100 Washington: 1950 No. 3265 MAMAIALS OF NORTHERN COLOMBIA PRELIMINARY REPORT NO. 6: RABBITS (LEPORIDAE), WITH NOTES ON THE CLASSIFICATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN FORMS By Philip Hershkovitz Rabbits collected by the author in northern Colombia during his tenure of the Walter Rathbone Bacon Traveling Scholarship include 18 tapitis representing Sylvilagus brasiliensis and 73 cottontails repre- senting Sylvilagus Jloridanus. The following review shows the above named to be the only recognizably vahd species of leporids indigenous to South America. All North and South American rabbits in the collection of the United States National Museum and the Chicago Natural History Museum were compared in preparing this report. Examples of Neotropical rabbits from other institutions, given below, were also examined. Available material included 34 of the 36 preserved types of South American rabbits. In the lists of specimens examined, the following abbreviations are used: A.M.N.H. American Museum of Natural History. B.M. British Museum (Natural History). CM. Carnegie Museum. C.N.H.M. Chicago Natural History Museum. M.N. H.N. Mus6um National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris. U.M.M.Z. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. U.S.N. M. United States National Museum. Z.M.T. Zoological Museum, Tring. 853011—50 1 327 328 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM vol. lOO The author expresses his appreciation to the authorities of European museums hsted above for permission to study specimens in their charge. Loan of material from American institutions is gratefully acknowl- edged. -

Morphological and Chromosomal Taxonomic Assessment of Sylvilagus Brasiliensis Gabbi (Leporidae)

Article in press - uncorrected proof Mammalia (2007): 63–69 ᮊ 2007 by Walter de Gruyter • Berlin • New York. DOI 10.1515/MAMM.2007.011 Morphological and chromosomal taxonomic assessment of Sylvilagus brasiliensis gabbi (Leporidae) Luis A. Ruedas1,* and Jorge Salazar-Bravo2 species are recognized (Hoffmann and Smith 2005). Syl- vilagus brasiliensis as thus construed is distributed from 1 Museum of Vertebrate Biology and Department of east central Mexico to northern Argentina at elevations Biology, Portland State University, Portland, from sea level to 4800 m, inhabiting biomes ranging from OR 97207-0751, USA, e-mail: [email protected] dry Chaco, through mesic forest, to highland Pa´ ramo 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech (Figure 1). University, Lubbock, TX 79409-3131, USA Most of the junior synonyms of S. brasiliensis currently *Corresponding author represent South American taxa, with Mesoamerican forms grouped into only two recognized subspecies: S. b. gabbi and S. b. truei (Hoffmann and Smith 2005). Based Abstract on specimens from Costa Rica and Panama, Allen (1877) described Lepus brasiliensis var. gabbi, which subse- The cottontail rabbit species, Sylvilagus brasiliensis,is quently was raised to species status (Lepus gabbi)by currently understood to be constituted by 18 subspecies Alston (1882) based on ‘‘differences in lengths of ear and ranging from east central Mexico to northern Argentina, tail between Central American and Brazilian (cottontails)’’. and from sea level to at least 4800 m in altitude. This Lyon (1904), with no further comment, included S. gabbi hypothesis of a single widespread polytypic species as a valid species in Sylvilagus, together with numerous remains to be critically tested. -

First Record for Uruará, South Western Para State, Amazonia, Brazil

International Journal of Research Studies in Biosciences (IJRSB) Volume 5, Issue 6, June 2017, PP 1-3 ISSN 2349-0357 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0365 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0365.0506001 www.arcjournals.org Sylvilagus Brasiliensis (Linnaeus 1758) (Mammalia, Lagomorpha, Leporidae): First Record for Uruará, South Western Para State, Amazonia, Brazil Roberto Portella de Andrade, Emil José Hernández-Ruz 1Curso de Pós-graduação em Biodiversidade e Conservação. Universidade Federal do Pará, Campus Universitário de Altamira. Rua Coronel José Porfírio, Altamira, Pará, Brazil Abstract: We present the first record of Sylvilagus brasiliensis to Uruará, south western Para State, Brazil. This location is outside the known distribution of species and also outside the domain of the Cerrado biome, which is usually associated with the geographic distribution of S. brasiliensis. The tapeti (Sylvilagus brasiliensis), Brazilian cottontail or forest cottontail is a rabbit 20-40 cm long (without the tail), and the adult individual may, weigh from 450 to up to 1,200 g. Their ears are short (40-61 mm) and his big dark eyes. It has elongated hind legs with four fingers while the former are shorter and five fingers. It features short, dense coat; brownish on the back and lighter on the belly. There are also sexual dimorphism, with females larger [1]. This species occurs from Tamaluipas South, Mexico along the east coast of Mexico (excluding the states of Yucatan, Quintana Roo, Campeche and) through Guatemala, (possibly) El Salvador, Honduras, eastern Nicaragua, eastern Costa Rica, Panama and through the northern half of South America (except at high altitudes), including Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, northern Argentina and most of Brazil. -

The Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge Holds the Distinction

The Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge holds the distinction of having the most diverse array of bird species found on any national wildlife refuge in the west. Introduction Established as a national refuge in 1930 by a Presidential Proclamation, the Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge is a haven for a diverse range of wildlife. Most of the refuge’s 37,600 acres are now inundated due to flooding by the Salton Sea. 1785 acres of agricultural fields and freshwater marsh remains manageable. Located 228 feet below sea level, the Salton Sea is one of the lowest places in the United States. The area was created in 1905, when a diversion structure on the Colorado River failed, and the river flowed into the Salton Sink for 16 months. Today, the waters of the Salton Sea have stabilized. Enjoying the Refuge’s Wildlife The study of wild animals in their natural habitat has become an increasingly popular pastime for many people. Viewing of wildlife can be greatly enhanced by a pair of binoculars or a spotting scope. This equipment allows the wildlife to be viewed at a distance, thus minimizing disturbance. Also, a good wildlife/birding guide is helpful in locating and identifying the various species. Wildlife species in this brochure have been grouped into five categories: birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Enjoying the Refuge’s Birdlife Numbers and species of birds you will see here varies according to season. Heavy migrations of waterfowl, marsh and shorebirds occur during spring and fall. Throughout the mild winter and spring a wide variety of songbirds and birds of prey are present.