519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment of President Donald John Trump The

1 116TH CONGRESS " ! DOCUMENT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 116–95 IMPEACHMENT OF PRESIDENT DONALD JOHN TRUMP THE EVIDENTIARY RECORD PURSUANT TO H. RES. 798 VOLUME XI, PART 7 Historic Materials Printed at the direction of Cheryl L. Johnson, Clerk of the House of Representatives, pursuant to H. Res. 798, 116th Cong., 2nd Sess. (2020) JANUARY 23, 2020.—Ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 39–530 WASHINGTON : 2020 VerDate Sep 11 2014 23:15 Jan 24, 2020 Jkt 039530 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 E:\HR\OC\HD095P29.XXX HD095P29 lotter on DSKBCFDHB2PROD with REPORTS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JERROLD NADLER, New York, Chairman ZOE LOFGREN, California DOUG COLLINS, Georgia, Ranking Member SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., STEVE COHEN, Tennessee Wisconsin HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia STEVE CHABOT, Ohio THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas KAREN BASS, California JIM JORDAN, Ohio CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana KEN BUCK, Colorado HAKEEM S. JEFFRIES, New York JOHN RATCLIFFE, Texas DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island MARTHA ROBY, Alabama ERIC SWALWELL, California MATT GAETZ, Florida TED LIEU, California MIKE JOHNSON, Louisiana JAMIE RASKIN, Maryland ANDY BIGGS, Arizona PRAMILA JAYAPAL, Washington TOM MCCLINTOCK, California VAL BUTLER DEMINGS, Florida DEBBIE LESKO, Arizona J. LUIS CORREA, California GUY RESCHENTHALER, Pennsylvania MARY GAY SCANLON, Pennsylvania, BEN CLINE, Virginia Vice-Chair KELLY ARMSTRONG, North Dakota SYLVIA R. GARCIA, Texas W. GREGORY STEUBE, -

Democracy and the NATO Alliance: Upholding Our Shared Democratic Values”

Prepared Statement for the Record “Democracy and the NATO Alliance: Upholding our Shared Democratic Values” Susan Corke Senior Fellow, German Marshall Fund and Director of Transatlantic Democracy Working Group House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, Energy, and the Environment U.S. House of Representatives November 13, 2019 Chairman Keating, Ranking Member Kinzinger, Distinguished Members of this Committee, thank you for holding this hearing and inviting me to testify before you on an issue that I believe is fundamental to American security and to our role as a leader of the democratic community of nations. It is a particular honor to be here today because Representatives Keating and Kinzinger have been two of the most principled voices in calling for a reinvigoration of democracy and the NATO Alliance as we contend with an era of authoritarian resurgence. On May 8th they both spoke powerfully at an event hosted by German Marshall Fund and the Transatlantic Democracy Working Group on the need to continue fighting for freedom and the ideals we value most, emphasizing this is in America’s interest. Representative Keating asked a pointed question this event, “What do we have that Russia and China don’t have? A coalition, NATO, that has resulted in 70 years of prosperity and peace.” This year is NATO’s 75th birthday and the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall; these anniversaries could have marked the success of the transatlantic project and the triumph of democracy. Instead, it is clear that after seven decades as the world’s preeminent military alliance, NATO’s future is in danger, facing urgent challenges that require immediate attention, including a recommitment to democratic values as a foundation of our security. -

Link to PDF Version

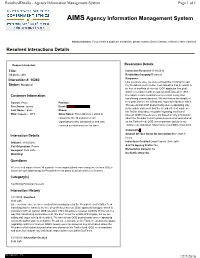

ResolvedDetails - Agency Information Management System Page 1 of 1 AIMS Agency Information Management System Announcement: If you create a duplicate interaction, please contact Gwen Cannon-Jenkins to have it deleted Resolved Interactions Details Reopen Interaction Resolution Details Title: Interaction Resolved:11/30/2016 34 press calls Resolution Category:Resolved Interaction #: 10260 Response: Like everyone else, we were excited this morning to read Status: Resolved the President-elect’s twitter feed indicating that he wants to be free of conflicts of interest. OGE applauds that goal, which is consistent with an opinion OGE issued in 1983. Customer Information Divestiture resolves conflicts of interest in a way that transferring control does not. We don’t know the details of Source: Press Position: their plan, but we are willing and eager to help them with it. The tweets that OGE posted today were responding only First Name: James Email: (b)(6) ' to the public statement that the President-elect made on Last Name: Lipton Phone: his Twitter feed about his plans regarding conflicts of Title: Reporter - NYT Other Notes: This contact is a stand-in interest. OGE’s tweets were not based on any information contact for the 34 separate news about the President-elect’s plans beyond what was shared organizations who contacted us and who on his Twitter feed. OGE is non-partisan and does not received our statement on the issue. endorse any individual. https://twitter.com/OfficeGovEthics Complexity( Amount Of Time Spent On Interaction:More than 8 Interaction Details hours Initiated: 11/30/2016 Individuals Credited:Leigh Francis, Seth Jaffe Call Origination: Phone Add To Agency Profile: No Assigned: Seth Jaffe Memorialize Content: No Watching: Do Not Destroy: No Questions We received inquires from 34 separate news organizations concerning tweets from OGE's twitter account addressing the President-elect's plans to avoid conflicts of interest. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, DECEMBER 12, 2011 No. 190 Senate The Senate met at 2 p.m., and was the State of Delaware, to perform the vacancies because Republicans were in called to order by the Honorable CHRIS- duties of the Chair. the majority in that court. So they TOPHER A. COONS, a Senator from the DANIEL K. INOUYE, wanted to defeat this competent State of Delaware. President pro tempore. woman, and that is what they did with Mr. COONS thereupon assumed the these vacancies still there in that PRAYER chair as Acting President pro tempore. court. The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- f They blocked the nomination of fered the following prayer: Richard Cordray to lead the Consumer RECOGNITION OF THE MAJORITY Let us pray. Financial Protection Bureau, despite LEADER God, our King, You are clothed in his obviously deep qualifications for majesty and strength. Your throne has The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- the job. He has a long history of pro- been established from the beginning pore. The majority leader is recog- tecting the middle class against unfair and You existed before time began. nized. practices by financial predators and he Help our lawmakers today to do their f would have been a great asset in our fight to protect Main Street from the work, striving to labor for Your glory. SCHEDULE Give them the purity of life and hon- kind of Wall Street greed that caused esty of purpose to walk in Your way. -

The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Keitel

in the service of the reich The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Keitel Edited with an introduction and epilogue by Walter Görlitz Translated by David Irving F FOCAL POINT The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Keitel © Musterschmidt-Verlag, Göttingen, 1961 English translation by David Irving © William Kimber and Co., London, 1965 Electronic edition © Focal Point Publications, London, 2003 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 66-14954 All rights reserved 2 Contents INTRODUCTION The Background and Career of Field-Marshal Keitel, 1882–1946 MEMOIRS 1: The Blomberg–Fritsch Crisis 2: From Austria to the End of the French Campaign 3: Prelude to the Attack on Russia 4: The Russian Campaign 5: Extracts from Keitel’s Wartime Letters to his Wife 6: The Bomb Plot of 20th July, 1944 7: The Last Days under Adolf Hitler 8: Afterthoughts EPILOGUE The Indictment Notes Index 3 Publisher’s Note The memoirs of Field-Marshal Keitel were written in manuscript in prison at Nuremberg beginning on 1st September, 1946. The original is in the posses- sion of the Keitel family. His narrative covering the years 1933 to 1938 is included in the German edi- tion, but in this English edition Keitel’s life up to 1937 is dealt with in the editor’s introduction, which contains many extracts from Keitel’s own account of those years. The translation of the mem- oirs themselves here begins with 1937, on page 36. On the other hand, some passages from the original manuscript, which were not included in the German edition, appear in this translation, as for example the description of the Munich crisis and the plan- ning discussions for the invasion of Britain. -

Operation ANTHROPOID 1941–1942

Michal BURIAN, Aleš KNÍŽEK Jiří RAJLICH, Eduard STEHLÍK Operation 1941–1942 ANTHROPOID Operation ANTHROPOID 1941–1942 ASSASSINATION ASSASSINATION Operation ANTHROPOID 1941–1942 Michal BURIAN, Aleš KNÍŽEK Jiří RAJLICH, Eduard STEHLÍK PRAGUE 2002 © Ministry of Defence of the Czech Republic – AVIS, 2002 ISBN 80-7278-158-8 To the reader: You are opening a book that tells a story of cruelty, heroism and betrayal in an original manner and without clichés. It is a story that has all the attributes of an ancient tragedy. It involves a blood-thirsty dictator, courageous avengers as well as a vile traitor. Yet an insuperable abyss separates it from ancient tragedy. The story of the assassination of the Deputy Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich is not the work of a Greek dramatist. It is a story written by life itself. And the thousands of dead Czech patriots are real indeed. The assassination of Heydrich was undeniably the most important deed of the Czech resistance movement against the Nazi occupation, on a European-wide scale. None of the resistance movements in those other countries occupied by the Nazis managed to hit such a highly placed target. That the assassination on 27 May 1942 was an entirely exceptional event is proved by the fact that whenever I talk to my foreign colleagues about the participation of Czech soldiers in the second world war, two moments are immediately brought to mind: our pilots in Britain and the assassination. Personally I would like to stress one often-overlooked aspect relating to the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich: the co-operation of the parachutists with representatives of the local resistance movement, who were ordinary Czech people as well as members of the Nation’s Defence and the Sokol Organisations. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2017 No. 18 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Victims were people from all types of And let me make it clear once again: called to order by the Speaker pro tem- backgrounds. Mr. Speaker, they all had This is not taxpayer funded money. pore (Mr. BOST). something in common. They were a si- Criminals paid for this. Criminals are f lent group of people who were preyed paying the rent on the courthouse and on by criminals. After the crime was they are paying for the system that DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO over, many suffered for years. they have created. TEMPORE Finally, Congress came up with a So what is the problem? The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- novel idea, a law that established the Well, the problem is, Mr. Speaker, fore the House the following commu- Crime Victims Fund to support victims only a fraction of that money is spent nication from the Speaker: of crime. But instead of using taxpayer each year for victims, depriving them WASHINGTON, DC, money for the fund, Congress had a dif- of needed services and that money. February 2, 2017. ferent idea. Why not force the crimi- More money continues to go in the I hereby appoint the Honorable MIKE BOST nals, the traffickers, the abusers, and fund every year because less and less of to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. -

How Campaign Finance Reform Restructured Campaigns and the Political World

Catholic University Law Review Volume 58 Issue 4 Summer 2009 Article 5 2009 Goodbye Soft Money, Hello Grassroots: How Campaign Finance Reform Restructured Campaigns and the Political World Laura MacCleery Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Laura MacCleery, Goodbye Soft Money, Hello Grassroots: How Campaign Finance Reform Restructured Campaigns and the Political World, 58 Cath. U. L. Rev. 965 (2009). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol58/iss4/5 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOODBYE SOFT MONEY, HELLO GRASSROOTS: HOW CAMPAIGN FINANCE REFORM RESTRUCTURED CAMPAIGNS AND THE POLITICAL WORLD Laura MacCleery+ I. IN TRO D UCTION ........................................................................................... 966 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF POLITICAL PARTY FUND-RAISING ........................... 971 A. Direct Mail Fund-raisingand the Seeds of a Republican R evolu tion .................................................................................................. 9 7 1 B. The Democrats'Response:Mixing Business with Politics................... 973 C. A Culture of Corruptionand Scandalon the Hill ................................ 975 D. The Rise of Soft Money ........................................................................ -

Presented by Openthegovernment.Org

Presented by OpenTheGovernment.org Friday, March 19 – 12:00 – 2:00 pm Center for American Progress 1333 H Street NW, 10th Floor On his first full day in office, President Obama committed his Administration "to creating an unprecedented level of openness in Government." To help meet that goal, the Administration issued an Open Government Directive and a new Memorandum on Freedom of Information Act and Attorney General Guidelines. The Administration has also launched an expansive effort to open up data to developers, advocates, and the public via Data.gov. During this program, our 5th annual Sunshine Week webcast, leading experts on transparency issues from inside and outside government will discuss if and how these initiatives have made the federal government more open, and what remains to be done. 12:00 Opening Remarks – Reece Rushing, Director of Government Reform, Center for American Progress -- Patrice McDermott, Director, OpenTheGovernment.org 12:05 Panel One: The Open Government Directive – Creating Lasting Government Openness? Norm Eisen, Special Counsel to the President for Ethics and Government Reform; Jim Harper, Director of Information Policy Studies, Cato Institute; John Wonderlich, Policy Director, Sunlight Foundation; and Patrice McDermott, Director, OpenTheGovernment.org (moderator) 12:50 Panel Two: FOIA – New Changes to the Oldest Public Access Law Miriam Nisbet, Director, Office of Government Information Services (OGIS); Melanie Pustay, Director, Department of Justice (DOJ) Office of Information Policy (OIP); Melanie Sloan, Executive Director, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington (CREW), Kevin Goldberg, American Society of News Editors (ASNE) counsel ; and Patrice McDermott, Director, OpenTheGovernment.org (moderator) 1:35 Panel Three –Data.gov – What can do it for me? Laura Beavers, National KIDS COUNT Coordinator, Annie E. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 163 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2017 No. 18 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was Victims were people from all types of And let me make it clear once again: called to order by the Speaker pro tem- backgrounds. Mr. Speaker, they all had This is not taxpayer funded money. pore (Mr. BOST). something in common. They were a si- Criminals paid for this. Criminals are f lent group of people who were preyed paying the rent on the courthouse and on by criminals. After the crime was they are paying for the system that DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO over, many suffered for years. they have created. TEMPORE Finally, Congress came up with a So what is the problem? The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- novel idea, a law that established the Well, the problem is, Mr. Speaker, fore the House the following commu- Crime Victims Fund to support victims only a fraction of that money is spent nication from the Speaker: of crime. But instead of using taxpayer each year for victims, depriving them WASHINGTON, DC, money for the fund, Congress had a dif- of needed services and that money. February 2, 2017. ferent idea. Why not force the crimi- More money continues to go in the I hereby appoint the Honorable MIKE BOST nals, the traffickers, the abusers, and fund every year because less and less of to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. -

Download the Report

HUMANITY IN ACTION ACTIVITY REPORT 2019-2020 1 OUR MISSION Humanity in Action is a transatlantic non-profit organization that supports liberal democracy, pluralism and human rights through unique educational programs for college and university students, recent graduates and young professionals with additional programs for high school students and teachers. We educate tomorrow’s leaders on past and present human rights challenges through critical historical as well as contemporary inquiries and cross-cultural dialogue. We connect an ever-growing international community committed to strengthening liberal democracy, human rights and pluralism. We inspire civic engagement to advance social equity, responsibility and justice. Through our work: • We affirm the importance of strengthening democratic values. • We foster environments in which individuals of diverse backgrounds and identities can engage openly and respectfully with contentious and challenging ideas and each other. • We support a vision of pluralistic societies that embrace differences and negotiate their boundaries through constructive political, social and personal dialogue and relationships. • We build a multinational, intergenerational community of emerging and established leaders who share values including justice, equity, anti-racism and anti-discrimination, pluralism and empathy. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Founder . 4 Netherlands . 33 Amsterdam Fellowship . 34 COVID-19 . 8 Action Projects . 35 Additional Programming . 36 The Fellowship . 10 Funders . 39 Bosnia and Herzegovina . 14 Poland . 40 Sarajevo Fellowship . 15 Warsaw Fellowship . 41 Action Projects . 16 Action Projects . 43 Additional Programming . 18 Additional Programming . 44 Funders . 20 Funders . 46 Denmark . 21 United States . 47 Copenhagen Fellowship . 22 John Lewis Fellowship . 48 Action Projects . 23 Detroit Fellowship . 49 Additional Programming . -

Historie Budov MF ČR

Aus der Geschichte der Gebäude des Finanzministeriums Autor: Ing. Jaroslava Musilová Technische Redaktion: Mag. Jiří Machonský Herausgeber: Finanzministerium Personalabteilung Referat Finanz- und Wirtschaftsinformationen Letenská 15, 118 10 Prag 1 Rechtsvorbehalt: Alle Rechte vorbehalten Die Vervielfältigung oder Verbreitung dieses Werks oder seiner Teile, ganz gleich, welcher Art, ist ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des Herausgebers verboten. ISBN: 978-80-85045-50-5 1. Auflage: 2013 Unverkäuflich © Finanzministerium der Tschechischen Republik Vorwort der Direktorin der Personalabteilung des Finanzministeriums der Tschechischen Republik Gegenwärtig residiert das Finanzministerium in mehreren Gebäuden Prags, wobei ein jedes der Gebäude über einen ganz eigenen Charakter verfügt. Die vorliegende Publikation ist das Ergebnis der über einen langen Zeitraum währenden Arbeit ihrer Autorin, Ing. Jaroslava Musilová, und birgt Interessantes über Architektur und Geschichte dieser Gebäude sowie über das Schicksal zweier bedeutender Persönlichkeiten. Die in der Publikation erscheinenden Fotografien stammen zu einem Großteil von der Autorin selbst. Die grafische Gestaltung verdanken wir Mag. Jiří Machonský. Gern möchte ich an dieser Stelle PhDr. Stanislav Kokoška vom Institut für Gegenwartsgeschichte der Akademie der Wissenschaften der Tschechischen Republik, den Ordensschwestern vom Karmel St. Josef in Prag, dem Institut der Englischen Fräulein in Prag sowie Ing. Pavel Kopecký und dessen Kollegen aus der Abteilung Wirtschafts- und Hausverwaltung des Finanzministeriums für ihr Entgegenkommen und ihre Hilfe bei der Suche nach Informationen und bei der Aufnahme der Fotografien in ansonsten der Öffentlichkeit nicht zugänglichen Interieuren danken. Sollten Sie als Leser dieser Publikation Interesse an weiteren Informationen zur Geschichte des Finanzministeriums, beginnend mit dem Jahr 1918, verspüren, so wenden Sie sich bitte an die Mitarbeiter des Bereichs Finanz- und Wirtschaftsinformationen.