Preface to the First English Edition of the Yasht

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

In the Alphabetic Order Q Follows A, a Follows E, C Follows C, 1J Follows N, S Follows S, I Follows Z

INDEX [In the alphabetic order q follows a, a follows e, c follows c, 1J follows n, s follows s, i follows z. In arranging words no distinction has been made between long and short vowels. Pahlavi anrllater forms are generally given in square brackets after the Avestan ones, ancl are entered separately only when there is a significant difference between the two.l Aban see Apas 273· A ban Niyayes 52; 271-2. Airyaman 56-7; his part at Fraso.kar<Jti, Aban Yast 73· 57. 242, 291. abstract divinities 23-4; 58, 59; 203. Airyanam Vaejah [f:ranve)] 144-5; 274- Aditi 55· S· Adityas 55; 83. Airyama isyo 56; 261; 263; 265. Adurbad i Mahraspandan 35; 288. Aiwisriithra [Aiwisriithrim] the 4th watch Aesma demon of Wrath, 87; companion ( giih) of the 24-hour day, from sunset till of the daevas, 201; flees at the last day midnight, 124; under the guardianship of before the Saosyant, 283; the Arabs are the fravasis, 124, 259. of his seed, 288. Aka Manah 283. aethrapati [erbad, herbad] 12. Akhtya 161. Afrasiyab see FralJrasyan *Ala demon of purpureal fever, 87 n. 20. afrinagan an "outer" religious ceremony, Amahraspand see Amasa Spanta 168; legends connected with the offerings Amestris xog; 112. made at it, 281. amaratat ,..., Ved. amrtatva-, "long life" after-life pagan belief in it beneath the or "immortality" II5 n. 32. earth, xog-xo, II2, IIS; in Paradise, no- Amaratat [Amurdad] personification of 12; Zoroastrian beliefs, 235-42, 328. "Long Life" and "Immortality", one of the Agni identified with Apam Napat, 45-6; 7 great Amasa Spantas (q.v.), 203; dis the nature of his primary concept, 69-70. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA WINTER ZEMESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 JOURNALJODae – Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1379 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1379 AY (Kadimi) Also Inside: Parliament oof the World’s Religions, Melbourne Parliamentt oof the World’s Religions:Religions: A shortshort hihistorystory Zarathustiss join in prayers for world peace in Pittsburgh Book revieew:w Thus Spake the Magavvs by Silloo Mehta PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA afezanajournal-winter2009-v15 page1-46.qxp 11/2/2009 5:01 PM Page 1 PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Winter / December 2009 Zemestan 1378 AY - 3747 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 4ss Coming Event [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 Parliament of the World’s Religions Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwalla [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 47 In the News Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla -

Change and Continuity in the Zoroastrian Tradition

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN THE ZOROASTRIAN TRADITION AN INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED ON 22 FEBRUARY 2012 BY ALMUT HINTZE Zartoshty Professor of Zoroastrianism in the University of London SOAS, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN THE ZOROASTRIAN TRADITION AN INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED ON 22 FEBRUARY 2012 BY ALMUT HINTZE Zartoshty Professor of Zoroastrianism in the University of London SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The publication of this booklet was supported by a grant of the Zoroastrian Trust Funds of Europe. Published by the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London), Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London, WC1H 0XG. © Almut Hintze, 2013 Cover image: K. E. Eduljee, Zoroastrian Heritage Layout: Andrew Osmond, SOAS British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 07286 0400 1 Printed in Great Britain at SOAS, University of London. Dedicated to the memory of the brothers Faridoon and Mehraban Zartoshty, to that of Professor Mary Boyce and of an anonymous benefactor. Table of Contents Preface by the Director of SOAS 5 Preface by the President of the Zoroastrian Trust Funds of Europe 7 Change and Continuity in the Zoroastrian Tradition 11 PrefacebytheDirectorofSOAS ThelinksbetweenSOASandtheZoroastriancommunityreachrightbacktothe early years of SOAS.In 1929 a consortium of Zoroastrian benefactors from Bombayfundedthe‘ParseeCommunity’sLectureshipinIranianStudies’atSOAS on -

Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices

Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices General Editor: John R. Hinnells The University, Manchester In the series: The Sikhs W. Owen Cole and Piara Singh Sambhi Zoroastrians Their Religious Beliefs and Practices MaryBoyce ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL London, Boston and Henley HARVARD UNIVERSITY, UBRARY.: DEe 1 81979 First published in 1979 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd 39 Store Street, London WC1E 7DD, Broadway House, Newtown Road, Henley-on-Thames, Oxon RG9 1EN and 9 Park Street, Boston, Mass. 02108, USA Set in 10 on 12pt Garamond and printed in Great Britain by Lowe & BrydonePrinters Ltd Thetford, Norfolk © Mary Boyce 1979 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Boyce, Mary Zoroastrians. - (Libraryof religious beliefs and practices). I. Zoroastrianism - History I. Title II. Series ISBN 0 7100 0121 5 Dedicated in gratitude to the memory of HECTOR MUNRO CHADWICK Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Cambridge 1912-4 1 Contents Preface XJ1l Glossary xv Signs and abbreviations XIX \/ I The background I Introduction I The Indo-Iranians 2 The old religion 3 cult The J The gods 6 the 12 Death and hereafter Conclusion 16 2 Zoroaster and his teaching 17 Introduction 17 Zoroaster and his mission 18 Ahura Mazda and his Adversary 19 The heptad and the seven creations 21 .. vu Contents Creation and the Three Times 25 Death and the hereafter 27 3 The establishing of Mazda -

Zoroastrainism

Zoroastrainism Unit 3: Religions that Originate in the Middle East/Southwest Asia Zoroastrians in the World Today Country Population[1][2] Percent Population India 69,000 0.006 Iran 25,271 0.03[3] United States 11,000 0.004 Afghanistan 10,000 0.031 United Kingdom 4,105 [4] 0.007 Canada 5,000 0.014 Pakistan 5,000 0.003 Singapore 4,500 0.087 Azerbaijan 2,000 0.022 Australia 2,700 0.012 Persian Gulf Countries 2,200 0.005 New Zealand 2,000 0.045 Total 137,776 - Zoroastrianism Timeline ∗ 1600 BCE – Birth of Zarathustra (or Zoroaster) ∗ But could be 1400 BCE or 628 BCE ∗ 600 BCE – Zorastrianism expands in Iran ∗ 220-650 CE – Zorastrian Sasanid Empire in Iran ∗ 651 CE – Persecution begins under the rule of Arab Muslims ∗ 900 CE – Beginning of migration to India ∗ 1381 CE – Mongols kill thousands of Zoroastrians in Iran ∗ 1640-1720 – Continued persecutions and forced conversions in Afghanistan and Iran (continues into the 21st century) ∗ 18th-21st centuries – Migration of Zoroastrains to N. America, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, etc. Origins of Zoroastrianism ∗Basis for Zoroastrianism is in Aryan religious traditions. ∗ Gods associated with nature ∗Above all the nature gods was one supreme god ∗ Called Ahura Mazda (or “Wise Lord”) The Life of Zoroaster ∗ Not much is really known about the true life of Zoroastrianism’s founder, Zarathustra Spitama (or Zoroaster in the Greek translation of his name) ∗ Might have been born into a noble family or a nomadic family or both ∗ Belief says that demons set out to kill the infant Zoroaster but he was -

18 Ideas of Self-Definition Among Zoroastrians in Post

18 IDEAS OF SELF-DEFINITION AMONG ZOROASTRIANS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY IRAN Sarah Stewart he tumultuous events of the Islamic Revolution of 1979 in Iran, followed Tby the eight-year war with Iraq, had a profound effect on the lives of all Iranians. Research conducted inside Iran on religious minorities during this time all but ceased. Moreover, the renewed religious fervour that characterized the post-revolutionary years in Iran, together with the continuation of discrim- inatory legislation, meant that many members of minority communities became reticent about discussing their religion – especially with foreigners. Information about the Zoroastrian religion and its people in Iran over the past 40 years has thus been fragmentary and is derived from a variety of sources. There are the accounts of those who left the country after the Revolution and settled elsewhere, some of them returning regularly to visit family members, maintain property that they continue to own, and to do business. There has also been a growing interest,Property amongst of I.B.Tauris young Iranian & Co. Ltdstudents and scholars, in the languages and cultures of pre-Islamic Iran. City dwellers – particularly the younger generation – use the internet with enthusiasm, and their websites and blogs provide insights into religious and social life, as well as the ways in which young Zoroastrians create and consolidate identities. In the past two decades, researchers from institutions both inside and outside Iran have had greater freedom of movement within the country and better -

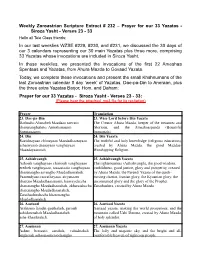

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 232 – Prayer for Our

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 232 – Prayer for our 33 Yazatas - Siroza Yasht - Verses 23 - 33 Hello all Tele Class friends: In our last weeklies WZSE #229, #230, and #231, we discussed the 30 days of our 3 calendars representing our 30 main Yazatas plus three more, comprising 33 Yazatas whose invocations are included in Siroza Yasht. In those weeklies, we presented the invocations of the first 22 Ameshaa Spentaas and Yazatas, from Ahura Mazda to Govaad Yazata. Today, we complete these invocations and present the small Khshnumans of the last Zoroastrian calendar 8 day ‘week’ of Yazatas, Dae-pa-Din to Aneraan, plus the three extra Yazatas Barjor, Hom, and Daham: Prayer for our 33 Yazatas - Siroza Yasht - Verses 23 - 33: (Please hear the attached .mp3 file for its recitation) Prayer Translation 23. Dae-pa-Din 23. Wise Lord before Din Yazata Dathusho Ahuraheh Mazdaao raevato The Creator Ahura Mazda, keeper of the treasures and kharenanghuhato, Ameshanaanm Glorious, and the Amashaaspands (Bountiful Spentanaanm Immortals) 24. Din 24. Din Yazata Razishtayaao chistayaao Mazdadhaatayaao The truthful and holy knowledge (religious education), ashaonyaao daenayaao vanghuyaao created by Ahura Mazda, the good Mazdaa- Maazdayasnoish. Worshipping Religion. 25. Ashishvangh 25. Ashishvangh Yazata Ashoish vanghuyaao chistoish vanghuyaao The righteousness (Ashishvangh), the good wisdom, eretheh vanghuyaao, rasaastaato vanghuyaao truthfulness, good justice, glory and prosperity, created kharenangho savangho Mazdadhaataheh. by Ahura Mazda, the Parendi Yazata of the quick- Paarendyaao raorathayaao, airyanaam moving chariot, Iranian glory, the Kyaanian glory, the khareno Mazdadhaatanaam, kaavayehecha unconsumed glory and the glory of the Prophet kharenangho Mazdadhaataheh, akharetahecha Zarathushtra, created by Ahura Mazda. -

History of Zoroastrianism, by M.N. Dhalla: (1938)

History of Zoroastrianism BY MANECKJI NUSSERVANJI DHALLA, PH. D., LITT.D. High Priest of the Parsis, Karachi, India AUTHOR OF Nyaishes or Zoroastrian Litanies, Zoroastrian Theology, Zoroastrian Civilization, Our Perfecting World – Zarathushtra’s Way of Life idha apãm vijasāiti vanghuhi daena māzdayasnaish vispāish avi karshvãn yāish hapta. “Henceforth from now may spread The Good Mazdayasnian Religion Over all the zones that are seven.” This electronic edition copyright 2003 by Joseph H. Peterson. Last updated March 2, 2021. Originally published: New York: Oxford University Press, London Toronto, 1938 TO KHAN BAHADUR KAVASJI HORMASJI KATRAK, O.B.E. at hvo vangheush vahyo nā aibijamyāt ye nāo erezush savangho patho sīshoit ahyā angheush astvato mananghaschā haithyeng āstīsh yeng ā shaetī ahuro aredro thwāvãns huzentushe spento mazdā. “May that man attain to better than the good Who helps teaching us the upright paths of blessedness Of this material world and that of the spirit – The veritable universe wherein pervades Ahura – That faithful, wise, and holy man is like unto thee, O Mazda.” - ZARATHUSHTRA Contents Foreword....................................................................................................i ABBREVIATIONS.....................................................................................ii CHAPTER I. THE SOURCES....................................................................1 CHAPTER II. AIRYANEM VAEJAH.........................................................5 THE GATHIC PERIOD – ABOUT 1000 B.C.......................................8 -

Sraosha - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

سروش http://www.arabdict.com/english-arabic/%D8%B3%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B4 Sraosha - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sraosha Sraosha From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Sraosha is the Avestan language name of the Zoroastrian yazata of "Obedience" or "Observance", which is also the literal meaning of his name. In the Middle Persian commentaries of the 9th-12th centuries, the divinity appears as S(a)rosh . This form Sor ūsh . Unlike many of the , وش appears in many variants in New Persian as well, for example Perso-Arabic other Yazatas (concepts that are "worthy of adoration"), Sraosha has the Vedic equivalent to Saraswati. Sraosha is also frequently referred to as the "Voice of Conscience", which overlaps with both "Obedience" and as his role as the "Teacher of Daena", Daena being the hypostasis of both "Conscience" and "Religion". Contents 1 In scripture 1.1 In Zoroaster's revelation 1.2 In the younger Avesta 2 In Zoroastrian tradition 3 References In scripture In Zoroaster's revelation Sraosha is already attested in the Gathas, the oldest texts of Zoroastrianism and believed to have been composed by Zoroaster himself. In these earliest texts, Sraosha is routinely associated with the Amesha Spentas, the six "Bounteous Immortals" through which Ahura Mazda realized ("created by His thought") creation. In the Gathas, Sraosha's primary function is to propagate the religion of Ahura Mazda to humanity, as Sraosha himself learned it from Ahura Mazda. This is only obliquely alluded to in these old verses but is only properly developed in later texts (Yasna 57.24, Yasht 11.14 etc.). -

YAZATA: the Persian Gods

™ YAZATA: The Persian Gods By Siavash Mojarrad and Dean Shomshak WrittenCredits by: Siavash Mojarrad and Dean Shomshak Developer: Eddy Webb and Dean Shomshak Editor: Genevieve Podleski Art Direction and Book Design: Brian Glass Artists: Trevor Claxton, Oliver Diaz, Andrew Hepworth, Imaginary Friends Studio, Mattias Kollros, Ron Lemen, Adrian Majkrazk, Christopher Swal and S Rich Thomas, C Cover Art: Rich Thomas I O N — T H E Y A Z A T A © 2010 CCP hf. All rights reserved. Reproduction without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden, except for the purposes of reviews, and for blank character sheets, which may be reproduced for personal use only. White Wolf and Scion are registered trademarks of CCP hf. All rights reserved. All rights reserved. All characters, names, places and text herein are copyrighted by CCP hf. CCP North America Inc. is a wholly owned subsidiary of CCP hf. This book uses the supernatural for settings, characters and themes. All mystical and supernatural elements are fiction and intended for entertainment purposes only. This book contains mature content. Reader discretion is advised. Check out White Wolf online at http://www.white-wolf.com 2 PRINTED ON DEMAND. ™ S C I O N YAZATA: — T The Persian Gods H E Y A Table of Contents Z THE YAZATA A The Yazata 7 T The Pantheon 8 A Purviews 14 Birthrights 19 Cosmology 28 Titans 31 THE GOD, THE BAD AND THE UGLY Introduction 37 The Strangers Rode Into Town 50 Mirages of Time 54 Outlaws! 55 Interrogation 58 The Vice of Killing 60 Showdown 61 Aftermath 63 Scene Charts 65 3 Cyrus stood in front of the heavy wrought-iron gate set into the stone wall. -

Purpose of Zoroastrian Life in This World

PURPOSE OF ZOROASTRIAN LIFE IN THIS WORLD : Zoroastrianism teaches us that our life in this world is a blessing and also a duty and struggle. It is a blessing, because God has given us the wonderful body with physical, mental, and spiritual powers. He has created everything that we require for maintaining our life, provided we work for the same. Every moment we receive blessings of God in one way or the other like rays of the sun, rains from the skies, plants and trees growing from the earth, and many other visible and invisible currents of Nature – are all blessings of God. Man’s Duties in life: Our life is also a duty. As human beings and as Zoroastrians, we have to do the duties of life towards God, towards ourselves, and towards others. We have a duty towards God, as He has given us our life and all good things in it. We have to discharge that duty by remembering Him, thanking Him by offering prayers, and by leading a virtuous and useful life. The prayer with a devoted heart and dedicated mind purifies our feelings, elevates our life, and leads us on the path of goodness. A Zoroastrian also has to do his duty to himself. Our body is a sacred weapon of our soul in this life. It is through the body that the soul can perform the duties of this life. It is, therefore, our duty to keep our body clean, pure, and healthy, so that we can receive the blessings of health, endurance, vitality and long life from God.