Ohio's Statute of Limitations for Medical Malpractice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Escs and the Ohio Revised Code

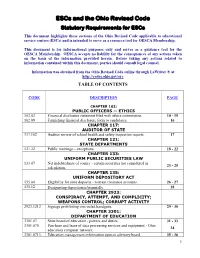

ESCs and the Ohio Revised Code Statutory Requirements for ESCs This document highlights those sections of the Ohio Revised Code applicable to educational service centers (ESCs) and is intended to serve as a resource tool for OESCA Membership. This document is for informational purposes only and serves as a guidance tool for the OESCA Membership. OESCA accepts no liability for the consequences of any actions taken on the basis of the information provided herein. Before taking any actions related to information contained within this document, parties should consult legal counsel. Information was obtained from the Ohio Revised Code online through LaWriter ® at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc TABLE OF CONTENTS CODE DESCRIPTION PAGE CHAPTER 102: PUBLIC OFFICERS -- ETHICS 102.02 Financial disclosure statement filed with ethics commission. 10 - 15 102.09 Furnishing financial disclosure form to candidates. 16 CHAPTER 117: AUDITOR OF STATE 117.102 Auditor review of school health and safety inspection reports. 17 CHAPTER 121: STATE DEPARTMENTS 121.22 Public meetings – exceptions. 18 - 22 CHAPTER 133: UNIFORM PUBLIC SECURITIES LAW 133.07 Net indebtedness of county - certain securities not considered in 23 - 25 calculation. CHAPTER 135: UNIFORM DEPOSITORY ACT 135.04 Eligibility for state deposits - warrant clearance accounts. 26 - 27 135.12 Designating depositories biennially. 28 CHAPTER 2923: CONSPIRACY, ATTEMPT, AND COMPLICITY; WEAPONS CONTROL; CORRUPT ACTIVITY 2923.1212 Signage prohibiting concealed handguns. 29 - 30 CHAPTER 3301: DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION 3301.07 State board of education - powers and duties. 31 - 33 3301.075 Purchase and lease of data processing services and equipment - Ohio 34 education computer network. 3301.0713 Education management information system advisory board. -

Village Officers Handbook

OHIO VILLAGE OFFICER’S HANDBOOK ____________________________________ March 2017 Dear Village Official: Public service is both an honor and challenge. In the current environment, service at the local level may be more challenging than ever before. This handbook is one small way my office seeks to assist you in meeting that challenge. To that end, this handbook is designed to be updated easily to ensure you have the latest information at your fingertips. Please feel free to forward questions, concerns or suggestions to my office so that the information we provide is accurate, timely and relevant. Of course, a manual of this nature is not to be confused with legal advice. Should you have concerns or questions of a legal nature, please consult your statutory legal counsel, the county prosecutor’s office or your private legal counsel, as appropriate. I understand the importance of local government and want to make sure we are serving you in ways that meet your needs and further our shared goals. If my office can be of further assistance, please let us know. I look forward to working with you as we face the unique challenges before us and deliver on our promises to the great citizens of Ohio. Thank you for your service. Sincerely, Dave Yost Auditor of State 88 East Broad Street, Fifth Floor, Columbus, Ohio 43215-3506 Phone: 614-466-4514 or 800-282-0370 Fax: 614-466-4490 www.ohioauditor.gov This page is intentionally left blank. Village Officer’s Handbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Home Rule I. Definition ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 II. -

The Ohio Sunshine Act: an Appraisal

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 1-1982 The Ohio Sunshine Act: An Appraisal Frederic White Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Frederic White, The Ohio Sunshine Act: An Appraisal, 16 Akron L. Rev. 243 (1982). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/545 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OHIO "SUNSHINE" ACT: AN APPRAISAL by FREDERIC WHITE* T HE OHIO OPEN MEETINGS or "Sunshine" law has existed in its present form since November 28, 1975 [hereinafter the "Sunshine Law" or "The Act"].' So-called open meeting legislation is neither new or unique to Ohio. Indeed, every state has enacted one or more open meetings laws.2 This article will examine the Sunshine Law to determine whether it has served its purpose, that is, making the processes of government more accessible to the citizens of the state of Ohio, and suggest some changes to increase the effectiveness of the legislation. I. ACCESS TO GOVERNMENT It has been stated succinctly that "America's heritage of English law does not include open government." '3 Indeed, Parliament conducted its business in both houses behind closed doors. Although the original reason for this was said to be for the protection of -

Lexis Advance® Ohio Core Offerings

Lexis Advance® Ohio Core Offerings OH Primary OH Enhanced OH Enhanced with Full Federal CITATORS Unlimited Shepard’s® Citations Service STATE CASES Ohio Courts of Appeals Cases from 1913 Ohio Miscellaneous Cases from 1823 Ohio Supreme Court Cases from 1821 STATE STATUTES AND LEGISLATION Ohio Advance Legislative Service Ohio Bill Tracking Reports Ohio Constitution Ohio Full-Text Bills Ohio Municipal Codes Ohio State & Federal Court Rules Page's Ohio Revised Code Annotated STATE AGENCY AND ADMINISTRATIVE MATERIALS Ohio Administrative Code Ohio Attorney General Opinions Ohio Board of Tax Appeals Orders Ohio Civil Rights Commission Decisions Ohio Department of Commerce, Division of Securities; Decisions Ohio Department of Taxation Information Releases Ohio Elections Commission Advisory Opinions Ohio Environmental Review Appeals Commission Ohio Ethics Commission Opinions Ohio Insurance Notices & Bulletins Ohio Market Conduct Examinations Ohio Public Utilities Commission Decisions Ohio State Employment Relations Board Decisions Ohio State Net Regulatory Text Ohio State Regulation Tracking Ohio Workers' Compensation Decisions Opinions of the Ohio Tax Commissioner Supreme Court of Ohio - Board of Commissioners on Grievances & Discipline The Register of Ohio FEDERAL CASES U.S. Supreme Court Cases, Lawyers’ Edition 6th Circuit Appellate, District and Bankruptcy Court CORE LAW REVIEWS & JOURNALS 300+ Law Reviews & Journals, including the Harvard Law Review, Florida Bar Journal and the Yale Law Journal Online FEDERAL CASES FEDERAL ADMINISTRATIVE MATERIALS U.S. Supreme Court from 1790 CFR – Code of Federal Regulations U.S. Court of Appeals from 1789 FR – Federal Register 11 Circuits, Federal Circuit and District of Columbia U.S. District Courts from 1789 FEDERAL LEGISLATIVE MATERIALS U.S. Bankruptcy Court from 10/79 United States Code Service - Titles 1 through 51 U.S. -

Ohio Legislative History 5

Note: a bill analysis does not present arguments for or against The Supreme Court of Ohio a proposed bill or any implication of its passage. It may or Ohio Legislative may not shed light on legislative intent. Law Library Information Series History The Supreme Court of Ohio has said bill analyses are not controlling. But because they contain impartial descriptions of bill content and are simply written, they 1. Ohio Case Law: Where to Find It may be referred to when deemed helpful to gain better 2. Legal Periodicals: Print, Microform & Online understanding (e.g. State v. American Dynamic Agency, Inc., 70 Ohio St.2d 41). 3. Government Documents 4. Ohio Legislative History 5. Federal Legislative History Locating and Accessing Bill Analyses 6. The U.S. Supreme Court • AV Room, 12th Floor: 104th GA (1961 forward) 7. Law Library Collection • Ohio stacks, 11th Floor: 119th to 123rd GA 8. The Online Catalog (1991-2000) 9. Ohio Legal Research • www.hannah.com (1989 forward) and 10. The Ohio Constitution www.legislature.state.oh.us (1997 forward). 11. Supreme Court of Ohio 12. Ohio Practice Materials ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 13. Audiovisual Collection Ohio Legislative Hotline Call 1.800.282.0253. Contact only in regard to legislation from the current or immediately preceding Ohio General Assembly (OGA). Ohio Historical Connection Bill Files Call 614.297.2510 or visit www.ohiohistory.org for information regarding bill files from 1949 to the OGA session immediately preceding the current one. Files are microfilmed at the close of each OGA and may contain alternate bill versions, fiscal notes, local impact statements, testimony from committee hearings and prepared statements read by witnesses. -

Supreme Court of Ohio Writing Manual Is the First Comprehensive Guide to Judicial Opinion Writing Published by the Court for Its Use

T S C of O WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing effective july 1, 2013 second edition Published for the Supreme Court of Ohio WRITING MANUAL A Guide to Citations, Style, and Judicial Opinion Writing MAUREEN O’CONNOR Chief Justice SHARON L. KENNEDY PATRICK F. FISCHER R. PATRICK DeWINE MICHAEL P. DONNELLY MELODY J. STEWART JENNIFER BRUNNER Justices STEPHANIE E. HESS Interim administrative Director The Supreme Court of Ohio Style Manual Committee HON. JUDITH ANN LANZINGER JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO Chair HON. TERRENCE O’DONNELL JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO HON. JUDITH L. FRENCH JUSTICE, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO STEVEN C. HOLLON ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO ARTHUR J. MARZIALE JR., Retired July 31, 2012 DIRECTOR OF LEGAL RESOURCES, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO SANDRA H. GROSKO REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO RALPH W. PRESTON, Retired July 31, 2011 REPORTER OF DECISIONS, THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO MARY BETH BEAZLEY ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF LAW AND DIRECTOR OF LEGAL WRITING, MORITZ COLLEGE OF LAW, THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY C. MICHAEL WALSH ADMINISTRATOR, NINTH APPELLATE DISTRICT The committee wishes to gratefully acknowledge the invaluable contributions of editor Pam Wynsen of the Reporter’s Office, as well as the excellent formatting assistance of John VanNorman, Policy and Research Counsel to the Administrative Director. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...........................................................................................................................ix -

Synthesis of Regulations and Laws Pertaining to Roadway/Rail Line Intersections on Ohio’S Local Transportation System

Synthesis of Regulations and Laws Pertaining to Roadway/Rail Line Intersections on Ohio’s Local Transportation System Prepared by: Donald Ludlow, George Kaulbeck, Andre Preto, Rahil Saeedi CPCS Transcom Inc. Prepared for: Ohio’s Research Initiative for Locals The Ohio Department of Transportation, Office of Statewide Planning & Research State Job Number 135806 April 2020 Final Report Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA/OH-2020-15 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date April 2020 Synthesis of Regulations and Laws Pertaining to Roadway/Rail 6. Performing Organization Code Line Intersections on Ohio’s Local Transportation System 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Donald Ludlow, George Kaulbeck, Andre Preto, Rahil Saeedi 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) CPCS Transcom Inc. Suite 500, 1000 Potomac Street, Northwest 11. Contract or Grant No. Washington, DC 20007 State Job #: 135806 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Ohio Department of Transportation Final Report 1980 West Broad Street, MS3280 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Columbus, Ohio 43223 15. Supplementary Notes Unless otherwise indicated, the opinions herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ohio’s Research Initiatives for Locals (ORIL) or the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT). This report provides an overview of the regulatory and legal framework as it is understood from a review of current legal and regulatory documentation. While CPCS makes efforts to validate and rectify any discrepancies, CPCS cannot warrant the accuracy of third-party data or assertions. -

Survey of Federal & State Laws

Survey of Federal & State Laws: Understanding Your Right To Be Treated Fairly and Without Discriminaon in Restaurants, Stores, and Other Businesses PUBLIC ACCOMMODATION LAWS BASED ON RACE, COLOR, AND/OR NATIONAL ORIGIN Last Updated : September 20, 2020 ** This survey is provided solely for informaonal purposes. Stop AAPI Hate does not warrant the accuracy of the informaon contained herein. Users are encouraged to seek advice from a licensed aorney regarding potenal violaons of any applicable public accommodaon laws. ** CAVEATS (1) This survey reviews general public accommodaon statutes under federal law and the laws of the states and District of Columbia. A review of case law interpreng the scope and applicaon of these statutes as well as a review of other statutes that may provide general an-discriminaon protecons or other indirect legal protecons are beyond the scope of this survey. (2) The scope of public accommodaon statutes differ from jurisdicon to jurisdicon based on differences in how key terms are statutorily defined and the existence of different statutory exempons to the statutes. (3) Addional public accommodaon laws may exist at the local (sub-federal/state) level. A comprehensive survey of which localies have enacted such laws is beyond the scope of this survey. However, in jurisdicons where no statewide public accommodaon laws for individuals based on race, color, or naonal origin exist, an aempt has been made to determine whether local public accommodaon laws exist in major urban centers in those jurisdicons. 1 (4) To the extent this survey indicates no private right of acon exists, that merely indicates no private right of acon is expressly authorized by that jurisdicon’s general public accommodaon statute. -

Council of State Governments Capitol

THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS SEPT 2011 CAPITOL RESEARCH SPECIAL REPORT Public Access to Official State Statutory Material Online Executive Summary As state leaders begin to realize and utilize the incredible potential of technology to promote trans- parency, encourage citizen participation and bring real-time information to their constituents, one area may have been overlooked. Every state provides public access to their statutory material online, but only seven states—Arkansas, Delaware, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, Utah and Vermont—pro- vide access to official1 versions of their statutes online. This distinction may seem academic or even trivial, but it opens the door to a number of questions that go far beyond simply whether or not a resource has an official label. Has the information online been altered—in- tentionally or not—from its original form? Who is in March:2 “You’ve often heard it said that sunlight is responsible for mistakes? How often is it updated? the best disinfectant. And the recognition is that, for Is the information secure? If the placement of a re- us to do better, it’s critically important for the public source online is not officially mandated or approved to know what we’re doing.” by a statute or rule, its reliability and accuracy are At the most basic level, free and open public access difficult to gauge. to the law that governs this country—federal and As state leaders have moved quickly to provide state—is necessary to create the transparency that is information electronically to the public, they may fundamental to a functional participatory democracy. -

Ohio Enhanced Content Indiana Enhanced Content Kentucky Enhanced Content

http://lngcentral.lexisnexis.com/ws/mcn/images/newlogo.gif Ohio Enhanced Content Indiana Enhanced Content Kentucky Enhanced Content CITATOR SERVICES* Cleveland State Law Review IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 1993 Unlimited SHEPARD'S Citation Service Columbus Business First (Ohio) IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 1994 Unlimited Auto-Cite Service *Usage of these services is unlimited when performed from Condemnation and Eminent Domain in IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 1995 the flat rate menus. Kentucky IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 1996 Consumer Law in Kentucky IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 1997 Coshocton Tribune (Ohio) IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 1998 6th Circuit - US Court of Appeals Cases Crain's Cleveland Business IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 1999 6th Circuit - US Court of Appeals, District & Criminal Tax Practice IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 2000 Bankruptcy Cases, Combined Dayton Business Journal (Ohio) IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 2001 6th Circuit - US District Court Cases Dayton Daily News IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 2002 7th Circuit - US Court of Appeals Cases Debtor/Creditor Relations in Kentucky IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 2003 7th Circuit - US Court of Appeals, District & DUI Law in Kentucky IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 2004 Bankruptcy Cases, Combined Election Law in Kentucky IN - Burns Indiana Code Annotated, 7th Circuit - US District Court Cases Employment Law in Kentucky Constitution, Court Rules & ALS, Combined Akron Law Review Entrepreneurial Business Law Journal -

Chapter 6 Tools for Understanding a Bill

Chapter 6 Tools for Understanding a Bill Photographed by Robin Stein, LSC Stein, Robin by Photographed Perry’s Victory, Rotunda How to Read a Bill Members of the General Assembly rely on the nonpartisan staff of the Legislative Service Commission (LSC) to draft the bills they request. While the drafting work is performed by LSC, members should become familiar with the form and structure of bills in order to have a thorough understanding of the law-making process. Members can learn about the contents of a bill in a variety of ways such as reading bill analyses and fiscal notes or listening to committee testimony and the comments of sponsors, other legislators, and lobbyists. However, there is no substitute for reading the bill itself. When reading a bill, a member may have questions relating to the meaning and clarity of the language. These are often the same questions that cause difficulties in administering the law when the bill is enacted. Occasionally, technical or legal terms are required, but normally the language of a bill should be simple and concise. If the language is not clear, the member should seek clarification. Elements of a Bill The Ohio Constitution requires legislation to be drafted in a specific format. The sample bill on the next page (Elements of a Bill) illustrates the major parts of a bill. At the beginning of each bill is a paragraph called the title. The title, which is required by the Ohio Constitution, lists the sections of the Revised Code being amended, enacted, or LSC A Guidebook for Ohio Legislators Page | 68 Chapter 6: Tools for Understanding a Bill repealed. -

America's Blame Culture

centner 00 fmt 8/14/08 7:10 AM Page i America’s Blame Culture centner 00 fmt 8/14/08 7:10 AM Page ii centner 00 fmt 8/14/08 7:10 AM Page iii America’s Blame Culture Pointing Fingers and Shunning Restitution Terence J. Centner Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina centner 00 fmt 8/14/08 7:10 AM Page iv Copyright © 2008 Terence J. Centner All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Centner, Terence J. America’s blame culture : pointing fingers and shunning restitution / by Terence J. Centner. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59460-483-6 (alk. paper) 1. Liability (Law)—United States. 2. Torts—United States. 3. Government liability—United States. I. Title. KF1250.C43 2008 346.7303—dc22 2008011656 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America centner 00 fmt 8/14/08 7:10 AM Page v To my wonderful family: Mary Ann, Ann Marie, and John Harry E. and Mary Ellen, Harry A., and Jean centner 00 fmt 8/14/08 7:10 AM Page vi centner 00 fmt 8/14/08 7:10 AM Page vii Contents Table of Cases xiii Table of Statutes xxi Table of Acts and Bills xxv Table of Text and Periodical Citations xxvii Acknowledgments xxxix Chapter 1 · A Culture of Blame 3 Other Views on Responsibility 6 Legal Systems and Communities 8 Liability Rules for Accidents 11 Shortcomings of Our Tort System 12 Notes 15 Chapter 2 · An Overview of American Tort Law 17 Observations from Europe and America 18