The Mozi and Just War Theory in Pre-Han Thought Chris Fraser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stability and Arms Control in Europe: the Role of Military Forces Within a European Security System

Stability and Arms Control in Europe: The Role of Military Forces within a European Security System A SIPRI Research Report Edited by Dr Gerhard Wachter, Lt-General (Rtd) and Dr Axel Krohn sipri Stockholm International Peace Research Institute July 1989 Copyright © 1989 SIPRI All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN 91-85114-50-2 Typeset and originated by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute Printed and bound in Sweden by Ingeniörskopia Solna Abstract Wachter, G. and Krohn, A., eds, Stability and Arms Control in Europe: The Role of Military Forces within a European Security System, A SIPRI Research Report (SIPRI: Solna, Sweden, 1989), 113 pp. This report presents the outcome of a project which was initiated at SIPRI in 1987. It was supported by a grant from the Volkswagen Stiftung of the Federal Republic of Germany. The introductory chapter by the editors presents a scenario for a possible future European security system. Six essays by active NATO and WTO military officers focus on the role of military forces in such a system. Various approaches to the tasks and size of military forces in this regime of strict non-provocative defence are presented with the intent of providing new ideas for the debate on restructuring of forces in Europe. There are 3 maps, 7 tables and 11 figures. Sponsored by the Volkswagen Stiftung. Contents Preface vi Acknowledgements viii The role of military forces within a European security system 1 G. -

Philosophy Course Offerings – Spring 2019 –

PHILOSOPHY COURSE OFFERINGS – SPRING 2019 – 200-level Courses (Tier Two) PHIL 272: Metaphysics | Andrew Cutrofello In Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates suggests that physics—the study of the physical world—can only tell us so much. There are things that physics cannot tell us about, such as the nature of justice or whether we have immortal souls. These topics belong to what we now call metaphysics. The prefix “meta-“ means “after” or “beyond.” Traditionally, it was the job of poets to deal with metaphysical topics. One of Plato’s goals is to explain the difference between poetic and philosophical approaches to metaphysical topics, while maintaining the difference between metaphysics and physics. Ever since, philosophers have struggled to articulate the relationship between physics, metaphysics, and poetry. Some have argued that as physics has become more sophisticated, it has swallowed up metaphysics. Others have argued that all metaphysics – even that of Plato – is just a kind of poetry. Still others have followed Plato in trying to carve out a special domain for metaphysics. In this class we survey various approaches to this problem. We will begin with Plato and then move on to Immanuel Kant, Kitaro Nishida, Susan Howe (a poet, writing about the philosopher Charles Peirce), and Werner Heisenberg (a physicist, writing about the relationship between physics and metaphysics). PHIL 274: Logic | Harry Gensler This course aims to promote reasoning skills, especially the ability to recognize valid reasoning. We'll study syllogistic, propositional, modal, and basic quantificational logic. We'll use these to analyze hundreds of arguments, many on philosophical topics like morality, free will, and the existence of God. -

Lawrence Kohlberg's Stages of Moral Development from Wikipedia

ECS 188 First Readings Winter 2017 There are two readings for Wednesday. Both are edited versions of Wikipedia articles. The first reading adapted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_Kohlberg's_stages_of_moral_development, and the second reading is adapted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethics. You can find the references for the footnotes there. As you read the article about moral development please think about you answered the Heinz Dilemma in class, and in which stage did your justification lie. I do not plan on discussing our answers to the Heinz Dilemma any further in class. As you read the ethic article, please think about which Normative ethic appeals to you, and why. This will be one of the questions we will discuss on Wednesday. My goal for both of these readings is to help you realize what values you bring to your life, and our course in particular. Lawrence Kohlberg's Stages of Moral Development from Wikipedia Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development constitute an adaptation of a psychological theory originally conceived by the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget. Kohlberg began work on this topic while a psychology graduate student at the University of Chicago[1] in 1958, and expanded upon the theory throughout his life. The theory holds that moral reasoning, the basis for ethical behavior, has six identifiable developmental stages, each more adequate at responding to moral dilemmas than its predecessor.[2] Kohlberg followed the development of moral judgment far beyond the ages studied earlier by Piaget,[3] who also claimed that logic and morality develop through constructive stages.[2] Expanding on Piaget's work, Kohlberg determined that the process of moral development was principally concerned with justice, and that it continued throughout the individual's lifetime,[4] a notion that spawned dialogue on the philosophical implications of such research.[5][6] The six stages of moral development are grouped into three levels: pre-conventional morality, conventional morality, and post-conventional morality. -

The Philosophy of War and Peace

THE PHILOSOPHY OF WAR AND PEACE Oleg Bazaluk1 — Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi State Pedagogical University (Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine) E-mail: [email protected] Tamara Blazhevych2 — Senior lecturer, Kyiv University of Tourism, Economy, and Law (Kyiv, Ukraine) E-mail: [email protected] In the paper the author comprehends ontology of the war and peace. Using the results of empiri- cal and theoretical research in the field of geophilosophy, as well as neuroscience, psychology, social philosophy and military history, the author comprehends the philosophy of war and peace. The author proves that the problem of war and peace originates in the features of forming men- tality. War and peace are the ways to achieve a regulatory compromise between manifestations of the active principle, which was initially laid in the foundation of the human mentality, and the influence of the external environment through natural selection; between the complicating needs of mental space as a totality of mentalities at the scale of the Earth and the possibilities of satisfying them; between the proclaimed idea that unites mental space, and the possibility of its implementa- tion. War and Peace regulate high-quality structure and manifestations of mental space: reduce the number of mentalities, whose structures predispose to aggression, and increase the number of men- talities, whose manifestations are directed at integration and cooperation. Through the proposed theory of war and peace, I have come to realize that, the state of peace for the evolving mental space includes the philosophy of war; the transition from peace to war depends mainly on the effective- ness of educational technology. -

Early Confucian Concept of Yi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Singapore Management University Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University Research Collection School of Social Sciences School of Social Sciences 2-2014 Early Confucian concept of Yi (议) and deliberative democracy Sor-hoon TAN Singapore Management University, [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591713515682 Follow this and additional works at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Citation TAN, Sor-hoon.(2014). Early Confucian concept of Yi (议) and deliberative democracy. Political Theory, 42(1), 82-105. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research/2548 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Sciences at Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Collection School of Social Sciences by an authorized administrator of Institutional Knowledge at Singapore Management University. For more information, please email [email protected]. PTX42110.1177/0090591713515682TanPolitical Theory 515682research-article2013 Ta n Published in Political Theory, Vol. Article42, Issue 1, February 2014, page 82-105 Political Theory 2014, Vol. 42(1) 82 –105 Early Confucian Concept © 2013 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: of Yi (议)and Deliberative sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0090591713515682 Democracy ptx.sagepub.com Sor-hoon Tan1 Abstract Contributors to the debates about the compatibility of Confucianism and democracy and its implications for China’s democratization often adopt definitions of democracy that theories of deliberative democracy are critical of. -

THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952)

Georg Hegel (1770-1831) ................................ 30 Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) ................. 32 Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach (1804-1872) ...... 32 John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) .......................... 33 Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) ..................... 33 Karl Marx (1818-1883).................................... 34 Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) ................ 35 Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914).............. 35 William James (1842-1910) ............................ 36 The Modern World 1900-1950 ............................. 36 Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) .................... 37 Ahad Ha'am (1856-1927) ............................... 38 Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) ............. 38 Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) ....................... 39 Henri Bergson (1859-1941) ............................ 39 Contents John Dewey (1859–1952) ............................... 39 Introduction....................................................... 1 THE PHILOSOPHY BOOK George Santayana (1863-1952) ..................... 40 The Ancient World 700 BCE-250 CE..................... 3 Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936) ................... 40 Introduction Thales of Miletus (c.624-546 BCE)................... 3 William Du Bois (1868-1963) .......................... 41 Laozi (c.6th century BCE) ................................. 4 Philosophy is not just the preserve of brilliant Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) ........................ 41 Pythagoras (c.570-495 BCE) ............................ 4 but eccentric thinkers that it is popularly Max Scheler -

Yin-Yang, the Five Phases (Wu-Xing), and the Yijing 陰陽 / 五行 / 易經

Yin-yang, the Five Phases (wu-xing), and the Yijing 陰陽 / 五行 / 易經 In the Yijing, yang is represented by a solid line ( ) and yin by a broken line ( ); these are called the "Two Modes" (liang yi 兩義). The figure above depicts the yin-yang cycle mapped as a day. This can be divided into four stages, each corresponding to one of the "Four Images" (si xiang 四象) of the Yijing: 1. young yang (in this case midnight to 6 a.m.): unchanging yang 2. mature yang (6 a.m. to noon): changing yang 3. young yin (noon to 6 p.m.): unchanging yin 4. mature yin (6 p.m. to midnight): changing yin These four stages of changes in turn correspond to four of the Five Phases (wu xing), with the fifth one (earth) corresponding to the perfect balance of yin and yang: | yang | yin | | fire | water | Mature| |earth | | | wood | metal | Young | | | Combining the above two patterns yields the "generating cycle" (below left) of the Five Phases: Combining yin and yang in three-line diagrams yields the "Eight Trigrams" (ba gua 八卦) of the Yijing: Qian Dui Li Zhen Sun Kan Gen Kun (Heaven) (Lake) (Fire) (Thunder) (Wind) (Water) (Mountain) (Earth) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Eight Trigrams can also be mapped against the yin-yang cycle, represented below as the famous Taiji (Supreme Polarity) Diagram (taijitu 太極圖): This also reflects a binary numbering system. If the solid (yang) line is assigned the value of 0 and the broken (yin) line is 1, the Eight Trigram can be arranged to represent the numbers 0 through 7. -

Mohist Theoretic System: the Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections with the Universal Values and Global Sustainability

Cultural and Religious Studies, March 2020, Vol. 8, No. 3, 178-186 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.03.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING Mohist Theoretic System: The Rivalry Theory of Confucianism and Interconnections With the Universal Values and Global Sustainability SONG Jinzhou East China Normal University, Shanghai, China Mohism was established in the Warring State period for two centuries and half. It is the third biggest schools following Confucianism and Daoism. Mozi (468 B.C.-376 B.C.) was the first major intellectual rivalry to Confucianism and he was taken as the second biggest philosophy in his times. However, Mohism is seldom studied during more than 2,000 years from Han dynasty to the middle Qing dynasty due to his opposition claims to the dominant Confucian ideology. In this article, the author tries to illustrate the three potential functions of Mohism: First, the critical/revision function of dominant Confucianism ethics which has DNA functions of Chinese culture even in current China; second, the interconnections with the universal values of the world; third, the biological constructive function for global sustainability. Mohist had the fame of one of two well-known philosophers of his times, Confucian and Mohist. His ideas had a decisive influence upon the early Chinese thinkers while his visions of meritocracy and the public good helps shape the political philosophies and policy decisions till Qin and Han (202 B.C.-220 C.E.) dynasties. Sun Yet-sen (1902) adopted Mohist concepts “to take the world as one community” (tian xia wei gong) as the rationale of his democratic theory and he highly appraised Mohist concepts of equity and “impartial love” (jian ai). -

Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy

Readings In Classical Chinese Philosophy edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe University of Michigan and Bryan W. Van Norden Vassar College Seven Bridges Press 135 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10010-7101 Copyright © 2001 by Seven Bridges Press, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. Publisher: Ted Bolen Managing Editor: Katharine Miller Composition: Rachel Hegarty Cover design: Stefan Killen Design Printing and Binding: Victor Graphics, Inc. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Readings in classical Chinese philosophy / edited by Philip J. Ivanhoe, Bryan W. Van Norden. p. cm. ISBN 1-889119-09-1 1. Philosophy, Chinese--To 221 B.C. I. Ivanhoe, P. J. II. Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William) B126 .R43 2000 181'.11--dc21 00-010826 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CHAPTER TWO Mozi Introduction Mozi \!, “Master Mo,” (c. 480–390 B.C.E.) founded what came to be known as the Mojia “Mohist School” of philosophy and is the figure around whom the text known as the Mozi was formed. His proper name is Mo Di \]. Mozi is arguably the first true philosopher of China known to us. He developed systematic analyses and criticisms of his opponents’ posi- tions and presented an array of arguments in support of his own philo- sophical views. His interest and faith in argumentation led him and his later followers to study the forms and methods of philosophical debate, and their work contributed significantly to the development of early Chinese philosophy. -

Mozi 31: Explaining Ghosts, Again Roel Sterckx* One Prominent Feature

MOZI 31: EXPLAINING GHOSTS, AGAIN Roel Sterckx* One prominent feature associated with Mozi (Mo Di 墨翟; ca. 479–381 BCE) and Mohism in scholarship of early Chinese thought is his so-called unwavering belief in ghosts and spirits. Mozi is often presented as a Chi- nese theist who stands out in a landscape otherwise dominated by this- worldly Ru 儒 (“classicists” or “Confucians”).1 Mohists are said to operate in a world clad in theological simplicity, one that perpetuates folk reli- gious practices that were alive among the lower classes of Warring States society: they believe in a purely utilitarian spirit world, they advocate the use of simple do-ut-des sacrifices, and they condemn the use of excessive funerary rituals and music associated with Ru elites. As a consequence, it is alleged, unlike the Ru, Mohist religion is purely based on the idea that one should seek to appease the spirit world or invoke its blessings, and not on the moral cultivation of individuals or communities. This sentiment is reflected, for instance, in the following statement by David Nivison: Confucius treasures the rites for their value in cultivating virtue (while virtually ignoring their religious origin). Mozi sees ritual, and the music associated with it, as wasteful, is exasperated with Confucians for valuing them, and seems to have no conception of moral self-cultivation whatever. Further, Mozi’s ethics is a “command ethic,” and he thinks that religion, in the bald sense of making offerings to spirits and doing the things they want, is of first importance: it is the “will” of Heaven and the spirits that we adopt the system he preaches, and they will reward us if we do adopt it. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

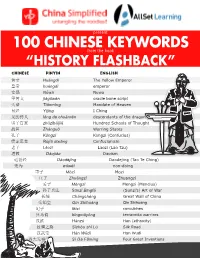

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai