Primary Pelvic Exenteration: Our Experience with 23 Patients from a Single Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curative Pelvic Exenteration for Recurrent Cervical Carcinoma in the Era of Concurrent Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect EJSO xx (2015) 1e11 www.ejso.com Review Curative pelvic exenteration for recurrent cervical carcinoma in the era of concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A systematic review H. Sardain a,b, V. Lavoue a,b,c,*, M. Redpath d, N. Bertheuil b,e, F. Foucher a,J.Lev^eque a,b,c a CHU de Rennes, Gynecology Department, Tertiary Surgery Center, Teaching Hospital of Rennes, Hopital^ Sud, 16, Bd de Bulgarie, 35000 Rennes, France b Universite de Rennes, Faculty of Medicine, 2 Henry Guilloux, 35000 Rennes, France c INSERM, ER440, Oncogenesis, Stress and Signaling (OSS), Rennes, France d McGill University, Department of Pathology, Jewish General Hospital, Cote^ Sainte Catherine, Montreal, QC, Canada e CHU de Rennes, Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Tertiary Surgery Center, Teaching Hospital of Rennes, Hopital^ Sud, 16, Bd de Bulgarie, 35000 Rennes, France Accepted 26 March 2015 Available online --- Abstract Objective: Pelvic exenteration requires complete resection of the tumor with negative margins to be considered a curative surgery. The pur- pose of this review is to assess the optimal preoperative evaluation and surgical approach in patients with recurrent cervical cancer to in- crease the chances of achieving a curative surgery with decreased morbidity and mortality in the era of concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Methods: Review of English publications pertaining to cervical cancer within the last 25 years were included using PubMed and Cochrane Library searches. Results: Modern imaging (MRI and PET-CT) does not accurately identify local extension of microscopic disease and is inadequate for pre- operative planning of extent of resection. -

Pelvic Exenteration for the Management of Pelvic Malignancies

Chapter 7 Pelvic Exenteration for the Management of Pelvic Malignancies Daniel Paramythiotis, Konstantinia Kofina and Antonios Michalopoulos Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/61083 Abstract Pelvic exenteration is a surgical procedure first described by Brunschwig in 1948 as a curative or palliative treatment for pelvic and perineal tumors. It is actually a radical operation, involving en bloc resection of pelvic organs, including reproductive structures, bladder, and rectosigmoid. In patients with recurrent cervical and vaginal malignancy, it is associated with a 5-year survival of more than 50%. In spite of advances in surgical management, consequences such as stomas, are still frequently unavoidable for radical tumor excision. Most candidates for this procedure have been diagnosed with recurrent cervical cancer that has previously been treated with surgery and radiation, or radiation alone. Complications of pelvic exenteration are more severe than those of standard resection of a colorectal carcinoma, so it is not commonly performed, including wound infection, wound dehiscence (also described as burst abdomen) the creation of fistulae (perineal-fecal, uretero-vaginal, between conduit and perineal wound), urinary tract infections, perineal hernias and intestinal obstruction. Patients need to be carefully selected and counseled about risks and long-term issues related to the surgery. A comprehensive evaluation is required in order to exclude unresectable or metastatic disease. Evolution of the technique through laparoscopy and minimally invasive surgery may result in a reduction of morbidity and mortality. Keywords: Pelvic exenteration, gynecologic cancer 1. Introduction Pelvic exenteration was first described by Brunschwig and his colleagues of New York’s Memorial Hospital in 1948 [1] and was initially performed as a palliative surgical intervention © 2015 The Author(s). -

Treating Cervical Cancer If You've Been Diagnosed with Cervical Cancer, Your Cancer Care Team Will Talk with You About Treatment Options

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 Treating Cervical Cancer If you've been diagnosed with cervical cancer, your cancer care team will talk with you about treatment options. In choosing your treatment plan, you and your cancer care team will also take into account your age, your overall health, and your personal preferences. How is cervical cancer treated? Common types of treatments for cervical cancer include: ● Surgery for Cervical Cancer ● Radiation Therapy for Cervical Cancer ● Chemotherapy for Cervical Cancer ● Targeted Therapy for Cervical Cancer ● Immunotherapy for Cervical Cancer Common treatment approaches Depending on the type and stage of your cancer, you may need more than one type of treatment. For the earliest stages of cervical cancer, either surgery or radiation combined with chemo may be used. For later stages, radiation combined with chemo is usually the main treatment. Chemo (by itself) is often used to treat advanced cervical cancer. ● Treatment Options for Cervical Cancer, by Stage Who treats cervical cancer? Doctors on your cancer treatment team may include: 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 ● A gynecologist: a doctor who treats diseases of the female reproductive system ● A gynecologic oncologist: a doctor who specializes in cancers of the female reproductive system who can perform surgery and prescribe chemotherapy and other medicines ● A radiation oncologist: a doctor who uses radiation to treat cancer ● A medical oncologist: a doctor who uses chemotherapy and other medicines to treat cancer Many other specialists may be involved in your care as well, including nurse practitioners, nurses, psychologists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and other health professionals. -

Once in a Lifetime Procedures Code List 2019 Effective: 11/14/2010

Policy Name: Once in a Lifetime Procedures Once in a Lifetime Procedures Code List 2019 Effective: 11/14/2010 Family Rhinectomy Code Description 30160 Rhinectomy; total Family Laryngectomy Code Description 31360 Laryngectomy; total, without radical neck dissection 31365 Laryngectomy; total, with radical neck dissection Family Pneumonectomy Code Description 32440 Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; with resection of segment of trachea followed by 32442 broncho-tracheal anastomosis (sleeve pneumonectomy) 32445 Removal of lung, pneumonectomy; extrapleural Family Splenectomy Code Description 38100 Splenectomy; total (separate procedure) Splenectomy; total, en bloc for extensive disease, in conjunction with other procedure (List 38102 in addition to code for primary procedure) Family Glossectomy Code Description Glossectomy; complete or total, with or without tracheostomy, without radical neck 41140 dissection Glossectomy; complete or total, with or without tracheostomy, with unilateral radical neck 41145 dissection Family Uvulectomy Code Description 42140 Uvulectomy, excision of uvula Family Gastrectomy Code Description 43620 Gastrectomy, total; with esophagoenterostomy 43621 Gastrectomy, total; with Roux-en-Y reconstruction 43622 Gastrectomy, total; with formation of intestinal pouch, any type Family Colectomy Code Description 44150 Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with ileostomy or ileoproctostomy 44151 Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with continent ileostomy 44155 Colectomy, -

Pelvic Exenteration As Ultimate Ratio for Gynecologic Cancers: Single‑Center Analyses of 37 Cases

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2019) 300:161–168 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-019-05154-4 GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY Pelvic exenteration as ultimate ratio for gynecologic cancers: single‑center analyses of 37 cases N. de Gregorio1 · A. de Gregorio1 · F. Ebner2 · T. W. P. Friedl1 · J. Huober1 · R. Hefty3 · M. Wittau4 · W. Janni1 · P. Widschwendter1 Received: 5 February 2019 / Accepted: 5 April 2019 / Published online: 22 April 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Background Pelvic exenterations are a last resort procedure for advanced gynecologic malignancies with elevated risks in terms of patients’ morbidity. Methods This single-center analysis reports surgical details, outcome and survival of all patients treated with exenteration for non-ovarian gynecologic malignancies at our university hospital during a 13-year time period. We collected data regarding patients and tumor characteristics, surgical procedures, peri- and postoperative management, transfusions, complications, and analyzed the impact on survival outcomes. Results We identifed 37 patients between 2005 and 2013 with primary or relapsed cervical cancer (59.5%), vulvar cancer (24.3%) or endometrial cancer (16.2%). Median age was 60 years and most patients (73%) had squamous cell carcinomas. Median progression-free survival was 26.2 months and median overall survival was 49.9 months. The 5-year survival rates were 34.4% for progression-free survival and 46.4% for overall survival. There were no signifcant diferences in progres- sion-free survival and overall survival with regard to disease entity. Patients with tumor at the resection margins (R1) had a nearly signifcantly worse progression-free survival (median: 28.5 vs. -

Seer Program Code Manual

THE SEER PROGRAM CODE MANUAL Revised Edition June 1992 CANCER STATISTICS BRANCH SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM DIVISION OF CANCER PREVENTION AND CONTROL NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH Effective Date: Cases Diagnosed January 1, 1992 The SEER Program Code Manual Revised Edition June 1992 Editors Jack Cunningham Lynn Ries Benjamin Hankey Jennifer Seiffert Barbara Lyles Evelyn Shambaugh Constance Percy Valerie Van Holten Acknowledgements The editors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Terry Swenson, Maureen Troublefield, Diane Licitra, and Jerome Felix of Information Management Services, Inc., in the preparation of the SEER Program Code Manual. The editors also wish to acknowledge the assistance of Dr. John Berg in preparation of the section on multiple primary determination for lymphatic and hematopoietic diseases. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION ....................................... vii COMPUTER RECORD FORMAT ............................................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS .............................. 5 REFERENCES .......................................................... 37 SEER CODE SUMMARY .................................................. 39 I BASIC RECORD IDENTIFICATION ...................................... 57 1.01 SEER Participant ........................................... 58 1.02 Case Number .............................................. 59 1.03 Record Number ............................................ 60 -

Introduction to Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecology Physiotherapy

INTRODUCTION TO PELVIC OBSTETRIC AND GYNAECOLOGY PHYSIOTHERAPY An Educational Resource Published by the Pelvic, Obstetric and Gynaecology Physiotherapy Contact: POGP Administration, Fitwise Management Ltd., Drumcross Hall, Bathgate, West Lothian EH48 4JT T: 01506 811077 E: [email protected] or visit the POGP website www.pogp.org.uk for further information. ©POGP 2015 for review 2018 Contents CCCCC Introduction .........................................................................................................3 Core skill framework.............................................................................................4 Obstetrics..............................................................................................................5 Urology, Gynaecology and Colorectal..................................................................8 Breast Oncology……………………………………………………..………...………………..….……..17 Appendices 1. Obstetric abbreviations ..........................................................................19 2. Obstetric terminology ............................................................................20 3. Urology/ Gynaecology terminology……………………………………..……………..26 4. Gynaecology surgery terminology…………………………………………..………....29 5. Colorectal terminology…………………………………………………..………………..…31 6. Advanced clinical objectives for performing internal examinations…….34 C o n t e n t s 1 T H R E Introduction It is acknowledged that physiotherapists may become involved in the management of pelvic, obstetric and gynaecology patients -

OBGYN Outpatient Surgery Coding

OBGYN Outpatient Surgery Coding Anatomy Anatomy • Hyster/o – uterus, womb • Uter/o – uterus, womb • Metr/o – uterus, womb • Salping/o – tube, usually fallopian tube • Oophor/o – ovary • Ovari/o - ovary Terminology • Colpo – vagina • Cervic/o – cervix, lower part of the uterus, the “neck” • Episi/o – vulva • Vulv/o – vulva • Perine/o – the space between the anus and vulva Hysterectomy • A hysterectomy is an operation to remove a woman's uterus. • A woman may have a hysterectomy for different reasons, including: • Uterine fibroids that cause pain • bleeding, or other problems. • Uterine prolapse, which is a sliding of the uterus from its normal position into the vaginal canal. Hysterectomy • There are around 30 hysterectomy CPT codes. • To find the correct code you have to first check: • the surgical approach and • extent of the procedure. Surgical Approaches • Abdominal – the uterus is removed via an incision in the lower abdomen • Vaginal – the uterus is removed via an incision in the vagina • Laparoscopic – the procedure is performed using a laparoscope , inserted via several small incisions in the body. • Their are also CPT codes for laparoscopic-assisted vaginal approach. In this procedure ,the scope is inserted via a small incisions in the vagina. Extent of Procedure • Total hysterectomy: It includes laparoscopically detaching the entire uterine cervix and body from the surrounding supporting structures and suturing the vaginal cuff. It includes bivalving, coring, or morcellating the excised tissues, as required. The uterus is then removed through the vagina or abdomen. • Subtotal, partial or supracervical hysterectomy: It is the removal of the fundus or op portion of the uterus only, leaving the cervix in place. -

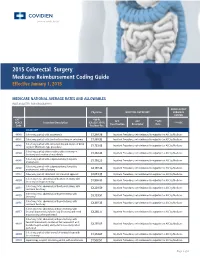

2015 Colorectal Surgery Medicare Reimbursement Coding Guide Effective January 1, 2015

2015 Colorectal Surgery Medicare Reimbursement Coding Guide Effective January 1, 2015 MEDICARE NATIONAL AVERAGE RATES AND ALLOWABLES (NOT ADJUSTED FOR GEOGRAPHY) AMBULATORY Physician HOSPITAL OUPATIENT SURGICAL CENTER CPT™* *MPFS APC APC **APC HCPCS Procedure Description (CF=$35.7547) ***ASC Classification Descriptor Rate Code Fac/Non-Fac COLECTOMY 44140 Colectomy, partial; with anastomosis $1,388.36 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare 44141 Colectomy, partial; with skin level cecostomy or colostomy $1,888.92 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare Colectomy, partial; with end colostomy and closure of distal 44143 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare segment (Hartmann type procedure) $1,723.02 Colectomy, partial; with resection, with colostomy or 44144 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare ileostomy and creation of mucofistula $1,832.43 Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic 44145 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare anastomosis) $1,716.23 Colectomy, partial; with coloproctostomy (low pelvic 44146 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare anastomosis), with colostomy $2,197.84 44147 Colectomy, partial; abdominal and transanal approach $2,013.35 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare Colectomy, total, abdominal, without proctectomy; with 44150 Inpatient Procedures, not reimbursed in outpatient or ASC by Medicare -

SJH Procedures

SJH Procedures - Gynecology and Gynecology Oncology Services New Name Old Name CPT Code Service ABLATION, LESION, CERVIX AND VULVA, USING CO2 LASER LASER VAPORIZATION CERVIX/VULVA W CO2 LASER 56501 Destruction of lesion(s), vulva; simple (eg, laser surgery, Gynecology electrosurgery, cryosurgery, chemosurgery) 56515 Destruction of lesion(s), vulva; extensive (eg, laser surgery, Gynecology electrosurgery, cryosurgery, chemosurgery) 57513 Cautery of cervix; laser ablation Gynecology BIOPSY OR EXCISION, LESION, FACE AND NECK EXCISION/BIOPSY (MASS/LESION/LIPOMA/CYST) FACE/NECK General, Gynecology, Plastics, ENT, Maxillofacial BIOPSY OR EXCISION, LESION, FACE AND NECK, 2 OR MORE EXCISE/BIOPSY (MASS/LESION/LIPOMA/CYST) MULTIPLE FACE/NECK 11102 Tangential biopsy of skin (eg, shave, scoop, saucerize, curette); General, Gynecology, single lesion Aesthetics, Urology, Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11103 Tangential biopsy of skin (eg, shave, scoop, saucerize, curette); General, Gynecology, each separate/additional lesion (list separately in addition to Aesthetics, Urology, code for primary procedure) Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11104 Punch biopsy of skin (including simple closure, when General, Gynecology, performed); single lesion Aesthetics, Urology, Maxillofacial, ENT, Thoracic, Vascular, Cardiovascular, Plastics, Orthopedics 11105 Punch biopsy of skin (including simple closure, when General, Gynecology, performed); each separate/additional lesion -

FY 2009 Final Addenda ICD-9-CM Volume 3, Procedures Effective October 1, 2008

FY 2009 Final Addenda ICD-9-CM Volume 3, Procedures Effective October 1, 2008 Tabular 00.3 Computer assisted surgery [CAS] Add inclusion term That without the use of robotic(s) technology Add exclusion term Excludes: robotic assisted procedures (17.41-17.49) New code 00.49 SuperSaturated oxygen therapy Aqueous oxygen (AO) therapy SSO2 SuperOxygenation infusion therapy Code also any: injection or infusion of thrombolytic agent (99.10) insertion of coronary artery stent(s) (36.06-36.07) intracoronary artery thrombolytic infusion (36.04) number of vascular stents inserted (00.45-00.48) number of vessels treated (00.40-00.43) open chest coronary artery angioplasty (36.03) other removal of coronary obstruction (36.09) percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA] (00.66) procedure on vessel bifurcation (00.44) Excludes: other oxygen enrichment (93.96) other perfusion (39.97) New Code 00.58 Insertion of intra-aneurysm sac pressure monitoring device (intraoperative) Insertion of pressure sensor during endovascular repair of abdominal or thoracic aortic aneurysm(s) New code 00.59 Intravascular pressure measurement of coronary arteries Includes: fractional flow reserve (FFR) Code also any synchronous diagnostic or therapeutic procedures Excludes: intravascular pressure measurement of intrathoracic arteries (00.67) 00.66 Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [PTCA] or coronary atherectomy Add code also note Code also any: SuperSaturated oxygen therapy (00.49) 1 New code 00.67 Intravascular pressure measurement of intrathoracic -

Intestinal Vaginoplasty: Which Should Be the Bowel Segment of Choice?

Academic Year 2014 – 2015 INTESTINAL VAGINOPLASTY: WHICH SHOULD BE THE BOWEL SEGMENT OF CHOICE? Cedric ROBBENS Promotor: Prof. Dr. Stan Monstrey Dissertation presented in the 2nd Master year in the programme of Master of Medicine in Medicine Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat. Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021. This page is not available because it contains personal information. Ghent Universit , Librar , 2021. Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat. Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021. This page is not available because it contains personal information. Ghent Universit , Librar , 2021. PREFACE My thesis discusses the use of bowel segments in vaginoplasty. I have chosen this subject because of my interest in reconstructive surgery. I am very grateful for the opportunity to write this work about a topic in my field of interest. I would like to thank all the people that helped bringing this literature review to a successful conclusion. First of all, the promotor of this literature review Prof. Dr. Stan Monstrey for the guidance and the counseling. My parents, Frank Robbens and Karine De Saedeleir, for giving me the chance to study and always supporting me. And finally, my sister Evy Robbens for revising this work. I end this preface with a quote by Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892) that represents the fundamental idea of this assignment: “That the powerful play goes on and you may contribute a verse. What will your verse be?” Cedric Robbens 08.04.2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS FRONT COVER TITLE PAGE