Project on “Intellectual Property and Gastronomic Tourism in Peru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Resources Institutions and Technical Efficiency by Smallholder Farmers: a Case Study from Cuatro Lagunas, Peru”

Water resources institutions and Technical efficiency by smallholder farmers: A case study from Cuatro Lagunas, Peru Denise Cavero Documento de Trabajo N° 116 Programa Dinámicas Territoriales Rurales Rimisp – Centro Latinoamericano para el Desarrollo Rural P á g i n a | 2 Este documento es el resultado del Programa Dinámicas Territoriales Rurales, que Rimisp lleva a cabo en varios países de América Latina en colaboración con numerosos socios. El pro- grama cuenta con el auspicio del Centro Inter- nacional de Investigaciones para el Desarrollo (IDRC, Canadá). Se autoriza la reproducción parcial o total y la difusión del documento sin fines de lucro y sujeta a que se cite la fuente. This document is the result of the Rural Terri- torial Dynamics Program, implemented by Rimisp in several Latin American countries in collaboration with numerous partners. The program has been supported by the Internation- al Development Research Center (IDRC, Cana- da). We authorize the non-for-profit partial or full reproduction and dissemination of this document, subject to the source being properly acknowledged. Cita / Citation: Cavero, D. 2012. “Water resources institutions and technical efficiency by smallholder farmers: A case study from Cuatro Lagunas, Peru”. Docu- mento de Trabajo N° 116. Programa Dinámicas Territoriales Rurales. Rimisp, Santiago, Chile. The autor is MSc (c) in International Develop- ment Studies at Wageningen University, The Netherlands. The author is thankful to GRADE for the provi- sion of the DTR survey data, CBC for the institu- tional support during her fieldwork in Cuatro Lagunas and RIMISP for the funding. © Rimisp-Centro Latinoamericano para el Desa- rrollo Rural Programa Dinámicas Territoriales Rurales Casilla 228-22 Santiago, Chile Tel +(56-2) 236 45 57 [email protected] www.rimisp.org/dtr Cavero, D. -

Resumen De Los Centros Poblados

1. RESUMEN DE LOS CENTROS POBLADOS 2. 1.1 CENTROS POBLADOS POR DEPARTAMENTO Según los resultados de los Censos Nacionales 2017: XII Censo de Población, VII de Vivienda y III de Comunidades Indígenas, fueron identificados 94 mil 922 centros poblados, en el territorio nacional. Son 5 departamentos los que agrupan el mayor número de centros poblados: Puno (9,9 %), Cusco (9,4 %), Áncash (7,8 %), Ayacucho (7,8 %) y Huancavelica (7,1 %). En cambio, los departamentos que registran menor número de centros poblados son: La Provincia Constitucional del Callao (0,01 %), Provincia de Lima (0,1 %), Tumbes (0,2 %), Madre de Dios (0,3 %), Tacna (1,0 %) y Ucayali (1,1 %). CUADRO Nº 1 PERÚ: CENTROS POBLADOS, SEGÚN DEPARTAMENTO Centros poblados Departamento Absoluto % Total 94 922 100,0 Amazonas 3 174 3,3 Áncash 7 411 7,8 Apurímac 4 138 4,4 Arequipa 4 727 5,0 Ayacucho 7 419 7,8 Cajamarca 6 513 6,9 Prov. Const. del Callao 7 0,0 Cusco 8 968 9,4 Huancavelica 6 702 7,1 Huánuco 6 365 6,7 Ica 1 297 1,4 Junín 4 530 4,8 La Libertad 3 506 3,7 Lambayeque 1 469 1,5 Lima 5 229 5,5 Loreto 2 375 2,5 Madre de Dios 307 0,3 Moquegua 1 241 1,3 Pasco 2 700 2,8 Piura 2 803 3,0 Puno 9 372 9,9 San Martín 2 510 2,6 Tacna 944 1,0 Tumbes 190 0,2 Ucayali 1 025 1,1 Provincia de Lima 1/ 111 0,1 Región Lima 2/ 5 118 5,4 1/ Comprende los 43 distritos de la Provincia de Lima 2/ Comprende las provincias de: Barranca, Cajatambo, Canta, Cañete, Huaral, Huarochirí, Huaura, Oyón y Yauyos Fuente: INEI - Censos Nacionales 2017: XII de Población, VII de Vivienda y III de Comunidades Indígenas. -

Las Regiones Geográficas Del Perú

LAS REGIONES GEOGRÁFICAS DEL PERÚ Evolución de criterios para su clasificación Luis Sifuentes de la Cruz* Hablar de regiones naturales en los tiempos actuales representa un problema; lo ideal es denominarlas regiones geográficas. Esto porque en nuestro medio ya no existen las llamadas regiones naturales. A nivel mundial la única región que podría encajar bajo esa denominación es la Antártida, donde aún no existe presencia humana en forma plena y sobre todo modificadora del paisaje. El medio geográfico tan variado que posee nuestro país ha motivado que a través del tiempo se realicen diversos ensayos y estudios de clasificación regional, con diversos criterios y puntos de vista no siempre concordantes. Señalaremos a continuación algunas de esas clasificaciones. CLASIFICACIÓN TRADICIONAL Considerada por algunos como una clasificación de criterio simplista, proviene de versión de algunos conquistadores españoles, que en sus crónicas y relaciones insertaron datos y descripciones geográficas, siendo quizá la visión más relevante la que nos dejó Pedro de Cieza de León, en su valiosísima Crónica del Perú (1553), estableciendo para nuestro territorio tres zonas bien definidas: la costa, la sierra o las serranías y la selva. El término sierra es quizá el de más importancia en su relato pues se refiere a la característica de un relieve accidentado por la presencia abundante de montañas (forma de sierra o serrucho al observar el horizonte). Este criterio occidental para describir nuestra realidad geográfica ha prevalecido por varios siglos y en la práctica para muchos sigue teniendo vigencia -revísense para el caso algunas de las publicaciones de nivel escolar y universitario-; y la óptica occidental, simplista y con vicios de enfoque,casi se ha generalizado en los medios de comunicación y en otros diversos ámbitos de nuestra sociedad, ya que el común de las gentes sigue hablando de tres regiones y hasta las publicaciones oficiales basan sus datos y planes en dicho criterio. -

Philadelphia City Guide Table of Contents

35th ANNUAL MEETING & SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS Philadelphia PHILADELPHIA MARRIOTT DOWNTOWN 1201 MARKET ST, PHILADELPHIA, PA 19107 APRIL 23-26, 2014 Philadelphia City Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS I. LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE ......................................................................................................................3 II. OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................................................3 III. WEATHER ........................................................................................................................................................................3 IV. GETTING AROUND .......................................................................................................................................................3 A. From the Airport .........................................................................................................................................................3 B. Around the City ..........................................................................................................................................................3 V. SAFETY .............................................................................................................................................................................4 VI. NEIGHBORHOODS .........................................................................................................................................................4 -

World Heritage Patrimoine Mondial 41

World Heritage 41 COM Patrimoine mondial Paris, June 2017 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Forty-first session / Quarante-et-unième session Krakow, Poland / Cracovie, Pologne 2-12 July 2017 / 2-12 juillet 2017 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List and/or on the List of World Heritage in Danger Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial et/ou sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu (Peru) (274) Sanctuaire historique de Machu Picchu (Pérou) (274) 22 - 25 February 2017 WHC-ICOMOS-IUCN-ICCROM Reactive Monitoring Mission to “Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu” (Peru) MISSION REPORT 22-25 February 2017 June 2017 Acknowledgements The mission would like to acknowledge the Ministry of Culture of Peru and the authorities and professionals of each institution participating in the presentations, meetings, fieldwork visits and events held during the visit to the property. This mission would also like to express acknowledgement to the following government entities, agencies, departments, divisions and organizations: National authorities Mr. Salvador del Solar Labarthe, Minister of Culture Mr William Fernando León Morales, Vice-Minister of Strategic Development of Natural Resources and representative of the Ministry of Environment Mr. -

Event Menu Pack

EVENT MENU CONTENTS BRUNCH HEALTHY & WELLNESS BUFFETS DESSERTS & SWEETS BBQs OR ACTION OPTIONS CRUISING BENTO BOX CANAPES OPEN BAR À LA CARTE LUNCH COCKTAIL RECEPTIONS À LA CARTE DINNER COFFEE BREAKS BRUNCH BACK TO CONTENTS Pastries & croissants (butter, chocolate & raisin) 7 Mini chicken burgers 8 Cakes & muffins (vanilla & chocolate) 7 Mini cheese burgers 10 Breads & crostini 7 Quiche with mushrooms with goat cheese 8 Selection of soup (tomato, asparagus & carrot) 7 Olives & thyme croissants 4 Omelette with vegetables, cheese & ham 9 Bagels with smoked salmon 9 Eggs benedict 13 Classic French toast 8 Variety of pies (chicken, spinach, 11 Waffles with berries & maple syrup 11 cheese & mushrooms) Hand cut Spanish or Parma ham 13 Sweet or salty crêpes 11 American style pancakes 11 Mini Black Angus steak sandwich 13 Spanish omelette with potatoes 10 Cold pasta with mozzarella, tomato & basil 8 Banana muffins 6 Greek or Caesar salad 7 Mixed green salad 4 Special dietary requests will be catered for. Minimum and maximum number of covers may apply to certain dishes. Minimum and maximum numbers and minimum menu charges may apply. Prices are per person and are quoted in Euro including VAT but excluding the 10% service fee. 3 BUFFETS GREEK INSPIRED BUFFET BACK TO CONTENTS Price per person 155 APPETIZERS & SALADS MAIN COURSE Stuffed vine leaves with rice & pine nuts Moussaka with eggplant Eggplant salad with walnuts & bell peppers Stuffed tomato with rice, raisins & pine nuts Wheat bread topped with tomato & feta cheese Cuttlefish casserole with -

Cozinha Internacional

COZINHA INTERNACIONAL Prof. Bruno Andreassi de Faro 2019 Copyright © UNIASSELVI 2019 Elaboração: Prof. Bruno Andreassi de Faro Revisão, Diagramação e Produção: Centro Universitário Leonardo da Vinci – UNIASSELVI Ficha catalográfica elaborada na fonte pela Biblioteca Dante Alighieri UNIASSELVI – Indaial. F237c Faro, Bruno Andreassi de Cozinha internacional. / Bruno Andreassi de Faro. – Indaial: UNIASSELVI, 2019. 255 p.; il. ISBN 978-85-515-0257-0 1.Culinária internacional – Brasil. II. Centro Universitário Leonardo Da Vinci. CDD 641.59 Impresso por: APRESENTAÇÃO O profissional que almeja possuir conhecimento amplo e estar capacitado para atender a diferentes tipologias de eventos no mundo gastronômico necessita estudar e praticar cozinhas de outros países. Com isso, é possível conhecer diferentes olhares muitas vezes sobre os mesmos ingredientes. Cada cultura gastronômica deriva de uma combinação única de geografia, história, povos com os quais se fazia comércio ou mesmo que conquistaram o local e com os ingredientes naturalmente disponíveis na região. Esse estudo por vezes auxilia ao cozinheiro compreender que o planeta todo se une pelos detalhes gastronômicos compartilhados. Muitos podem pensar, por exemplo, que na Ásia se come pimenta há milênios, contudo somente depois de os portugueses e espanhóis virem às Américas que as pimentas foram levadas e comercializadas por lá. Atualmente é impensável degustar pratos da Tailândia, Vietnã, China ou Índia sem sentir o sabor das pimentas. Da mesma forma, a batata, que é tão importante na Europa, é nativa da América do Sul, principalmente da região do Peru. Os nativos peruanos executavam receitas das mais distintas com os milhares de espécies de batata disponíveis, contudo ao chegarem à Europa, passaram a ser preparadas com o olhar europeu e combinadas com ingredientes do velho continente. -

English All List

Wine Sparkling Residual Award Category Producer Wine Vintage Country Region % Variety 1 % Variety 2 Inporter or Distributor No. Sugar Cabernet 13328 DG Still Red BODEGA NORTON CABERNET SAUVIGNON RESERVA 2014 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 ENOTECA CO., LTD. Sauvignon Cabernet 13326 DG Still Red BODEGA NORTON GERNOT LANGES 2012 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 60 Malbec 20 ENOTECA CO., LTD. Sauvignon Cabernet VINOS YAMAZAKI CO., 13003 DG Still Red BODEGAS FABRE S.A. VINALBA RESERVA CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2015 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Sauvignon LTD 13517 DG Still Red MENDOZA VINEYARDS R AND B MALBEC 2013 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Malbec CENTURY TRADING CO., 13524 DG Still Red MYTHIC ESTATE MYTHIC BLOCK MALBEC 2013 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Malbec LTD. 10917 DG Still White PAMPAS DEL SUR EXPRESION ARGENTINA TORRONTES 2016 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Torrontes FOODEM CO., LTD. 12885 DG Still Red VINITERRA SINGLE VINEYARD 2013 ARGENTINA MENDOZA 100 Malbec TOA SHOJI CO., LTD 12270 DG Still Red BODEGA EL ESTECO DON DAVID TANNAT RESERVE 2014 ARGENTINA SALTA 100 Tannat SMILE CORP. 14059 DG Still White CHAKANA MAIPE TORRONTES 2016 ARGENTINA SALTA 100 Torrontes OVERSEAS CO., LTD. Cabernet TOKO TRADING CO., 12728 DG Still Red ELEMENTOS ELEMENTOS CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2016 ARGENTINA SALTA 100 Sauvignon LTD 10532 DG Still White BODEGAS CALLIA ALTA CHARDONNAY - TORRONTES 2016 ARGENTINA SAN JUAN 60 Chardonnay 40 Torrontes MOTTOX INC. SOUTH VINOS YAMAZAKI CO., 11578 DG Still Red 3 RINGS 3 RINGS SHIRAZ 2014 AUSTRALIA 100 Shiraz AUSTRALIA LTD Cabernet ASAHI BREWERIES, 11363 DG Still Red KATNOOK ESTATE KATNOOK ESTATE CABERNET SAUVIGNON 2012 AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA 100 Sauvignon LTD. ASAHI BREWERIES, 11365 DG Still White KATNOOK ESTATE KATNOOK ESTATE CHARDONNAY 2013 AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA 100 Chardonnay LTD. -

Summer University Project Book 2009

SUMMERUNIVERSITYPROJECT BOOK2009 Imprint ISSN 1028-0642 Université d’été, AEGEE-Europe Summer University book Publisher Summer University Coordination Team [email protected] www.aegee.org/su Editor Dea Cavallaro Booklet design Dea Cavallaro Cover Illustration Mario Giuseppe Varrenti Circulation 5000 Project Management - SUCT Katrin Tomson Dea Cavallaro Dario Di Girolamo Bojan Bedrač Percin Imrek CONTENTS Introduction pag. 7 Language Course & Language Course pag. 17 Plus Summer Course pag. 51 Travelling Summer pag. 99 University Summer Event pag. 151 Appendix pag. 175 -How to Apply pag. 177 -Index by Organizer pag. 180 -Index by Date pag. 184 INTRODUCTION “Own only what you can carry with you; know languages, know countries, know people. Let your memory be your travel bag.” Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn Dear reader, You are holding a special book in your hand that may open you the door to unforgettable experiences. Please, do not mistake it for one of those high gloss travel catalogues you page through before booking an all inclusive holiday. The Summer University is so much more than that; and I do sincerely hope this year you will discover the secret of one of the most fascinating projects of AEGEE. Once you lived it, you will never want to miss it again. You have the choice to experience countries and places far be- yond the typical tourism hot spots. You have the choice between such diverse topics like language, history, photography, music, sports, travel - but always under the premise of multiculturalism. You have the choice to spend 2-4 weeks with people from more than 20 (European) countries offering you the unique chance to discover the life and fascination of one or more nations by taking the perspective of its inhabitants. -

Geosites and Geotouristic Attractions Proposed for the Project Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua, Peru

Geoheritage (2018) 10:707–729 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-018-0307-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Geosites and Geotouristic Attractions Proposed for the Project Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua, Peru Andrzej Gałaś1 & Andrzej Paulo1 & Krzysztof Gaidzik2,3 & Bilberto Zavala4 & Tomasz Kalicki5 & Danitza Churata4 & Slávka Gałaś1 & Jersey Mariño4 Received: 15 July 2016 /Accepted: 18 May 2018 /Published online: 7 June 2018 # The Author(s) 2018 Abstract The Colca Canyon (Central Andes, Southern Peru), about 100 km long and 1–3 km deep, forms a magnificent cross section of the Earth’s crust giving insight into mutual relations between lithostratigraphical units, and allowing relatively easy interpretation of the fascinating geological history written in the rocky beds and relief. Current activity of tectonic processes related to the subduction of the Nazca plate beneath the South American Plate exposed the geological heritage within study area. Well- developed tectonic structures present high scientific values. The volcanic landforms in the Valley of the Volcanoes and around the Colca Canyon include lava flows, scoria cones and small lava domes. They represent natural phenomena which gained recognition among tourists, scientists and local people. Studies performed by the Polish Scientific Expedition to Peru since 2003 recognized in area of Colca Canyon and Valley of the Volcanoes high geodiversity, potential for geoturism but also requirements for protectection. The idea of creating geopark gained recently the approval of regional and local authorities with support from the local National Geological Survey (INGEMMET). The Geopark Colca and Volcanoes of Andagua would strengthen the relatively poor system of the protected areas in the Arequipa department, increasing the touristic attractiveness and determine constraints for sustained regional development. -

Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean 363.1098 Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean

Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean 363.1098 Report on the Security Sector in Latin America and the Caribbean. R425 / Coordinated by Lucia Dammert. Santiago, Chile: FLACSO, 2007. 204p. ISBN: 978-956-205-217-7 Security; Public Safety; Defence; Intelligence Services; Security Forces; Armed Services; Latin America Cover Design: Claudio Doñas Text editing: Paulina Matta Correction of proofs: Jaime Gabarró Layout: Sylvio Alarcón Translation: Katty Hutter Printing: ALFABETA ARTES GRÁFICAS Editorial coordination: Carolina Contreras All rights reserved. This publication cannot be reproduced, partially or completely, nor registered or sent through any kind of information recovery system by any means, including mechanical, photochemical, electronic, magnetic, electro-visual, photocopy, or by any other means, without prior written permission from the editors. First edition: August 2007 I.S.B.N.: 978-956-205-217-7 Intellectual property registration number 164281 © Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, FLACSO-Chile, 2007 Av. Dag Hammarskjöld 3269, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile [email protected] www.flacso.cl FLACSO TEAM RESPONSIBLE FOR THE PREPARATION OF THE REPORT ON THE SECURITY SECTOR Lucia Dammert Director of the Security and Citizenship Program Researchers: David Álvarez Patricia Arias Felipe Ajenjo Sebastián Briones Javiera Díaz Claudia Fuentes Felipe Ruz Felipe Salazar Liza Zúñiga ADVISORY COUNCIL Alejandro Álvarez (UNDP SURF LAC) Priscila Antunes (Universidad Federal de Minas Gerais – Brazil) Felipe -

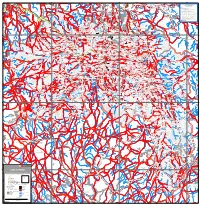

UGEL ESPINAR O Cerro Salla Lori

-71 .67 -71 .34 -71 VELILLE 617316 240494 C Soromisa Callejon Pampa 112885 e Consapata ") sa $+ Chaychapampa r a ome o 4 *# 652213 ") ro h c or 613309 *# y 0 400 o S 0 (! 210738 M c 516931 a Cerr lu 0 C Pukañan Cerro Silluta i Cerros Occorotoñe n a 0 e sa a o im C r 539319 Rosaspata # y C r r Huarcachapi / Qquellabamba a * Cerr c o o # o o Celopinco u r %, LAGO Huallataccota * Cerro Incacancha c C c Q a c a er Cerro Quirma Q 119397 *# 222362 a a Q c o p p Cerro Huacot 530275 Q a UGEL CHUMBIVILCAS l e d n C u o LANGUI l c d d r l I M m A Q Carta Educativa 2018 l i a a r a . a is Hilatunga d a C . o i n o a o CHECCA p i u *# C F C C . a h a LAYO . p r 617660 z a C d u a S L s R Sausaya u a u c e i p h r R o Q u u y c e a a c a l Q i Elaborada por la Unidad de Estadística del r e r u A i a Ccochapata y o c l n t r Cerro Mauro Moa 110101 Cerro Oquesupa n a Taypitunga t u r h i t . c am ") Exaltacion o o i Q i P a C a n d r a m 4000 e ta P 527487 Campo Villa c o a h .